On 11 October, a three-day meeting of the Synod, or church council, of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, finished in Istanbul. It gave further confirmation that Ukraine is on the path to receiving church independence from Moscow – and healing its schism, which has for nearly thirty years divided the world’s second largest Orthodox nation.

Although President Poroshenko triumphantly announced that in result of the meeting Ukraine had received the long-awaited Tomos, or decree of Church independence – a claim circulated in Ukraine with great enthusiasm, this is not true. Indeed, now Orthodox Church independence for Ukraine is indeed now a question of “when,” not “if,” and many were anticipating that the Tomos would be granted at this Synod. However, the recent decisions made in Istanbul, the residence of the Ecumenical Patriarch, are much more nuanced. Euromaidan Press explains how we got to this point and what’s next for the Orthodox Church in Ukraine.

What happened?

The Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, who also carries the title of Patriarch of Constantinople, a tribute to the city’s role as a center of Christianity during the days of the Byzantine empire, is working on making the Ukrainian Church independent from Moscow, or autocephalous. This has been going on since 2016, when the Ukrainian parliament appealed to Patriarch Bartholomew to grant this autocephaly.

This appeal was precipitated by Russia’s undeclared war against Ukraine. One of Ukraine’s three Orthodox Churches, and the only one recognized as legitimate by the rest of the world Orthodoxy – the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC MP) is subjugated to Moscow. It is extensively used as an instrument of Russia’s geopolitical influence over Ukraine and is one of the pillars of the “Russian world,” a neoimperial concept Russia uses to expand its influence and oppose the West. At the same time, Ukraine has two other Churches, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC KP) and Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC), regarded by the 15 autocephalous churches of the world as schismatic.

This is now all changing. The announcement issued by the Synod on 11 October brings Ukraine one more step closer to having a legitimate independent Orthodox Church, as well as ending the religious isolation of millions of Orthodox faithful in Ukraine.

Wait, are there so many Orthodox Churches in Ukraine, what’s the difference between them?

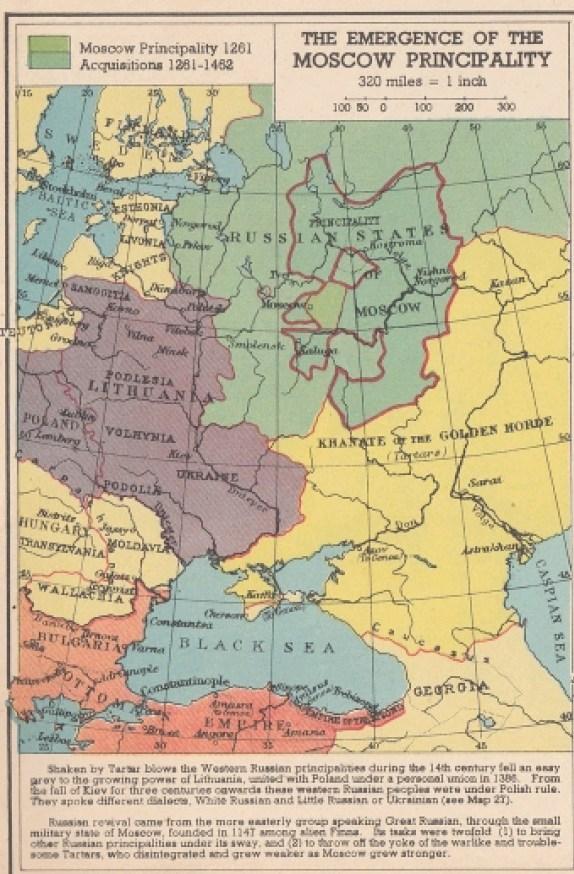

It all goes back to 1240, when the Tatar-Mongol invasion devastated the central part of the medieval kingdom of Kyivan Rus and divided its heritage between two emerging principalities – Moscow and Lithuania-Poland. The Church of the Kyivan Rus, which was an integral part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, was divided as well. The Moscow part split off and became the Moscow Patriarchate. In 1686, the Ecumenical Patriarchate agreed to give its Lithuania-Poland part, the Kyiv Metropoly, to be managed by the Moscow Church, under certain conditions. This part of the church is today the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. Is now headed by Metropolitan Onufriy and is subordinated to the Russian Orthodox Church, although claiming to enjoy autonomy.

After the Russian empire started disintegrating in 1917, the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC), headed by Vasyl Lypkivskyi, was proclaimed in Kyiv in 1921. It is crushed by Ukraine’s new Bolshevik government. In 1990, the UAOC was renewed in Ukraine. It is since 2015 headed by Metropolitan Makariy.

In 1991, after the proclamation of the independence of Ukraine, Metropolitan Filaret who headed the UOC MP proclaims autocephaly from the Moscow Patriarchate – a move which was not supported by everyone in UOC MP and the Moscow Patriarchate, i.e. the Russian Orthodox Church, itself. In 1992, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC KP) was formed. It is still led by Filaret, now a Patriarch.

Makariy and Filaret had been anathematized, or excommunicated, by the Russian Orthodox Church, meaning that they and the churches they lead were not recognized by the rest of the world Orthodoxy. Only the UOC MP was in communion with the rest of the world Orthodox Churches. Up till now, that is.

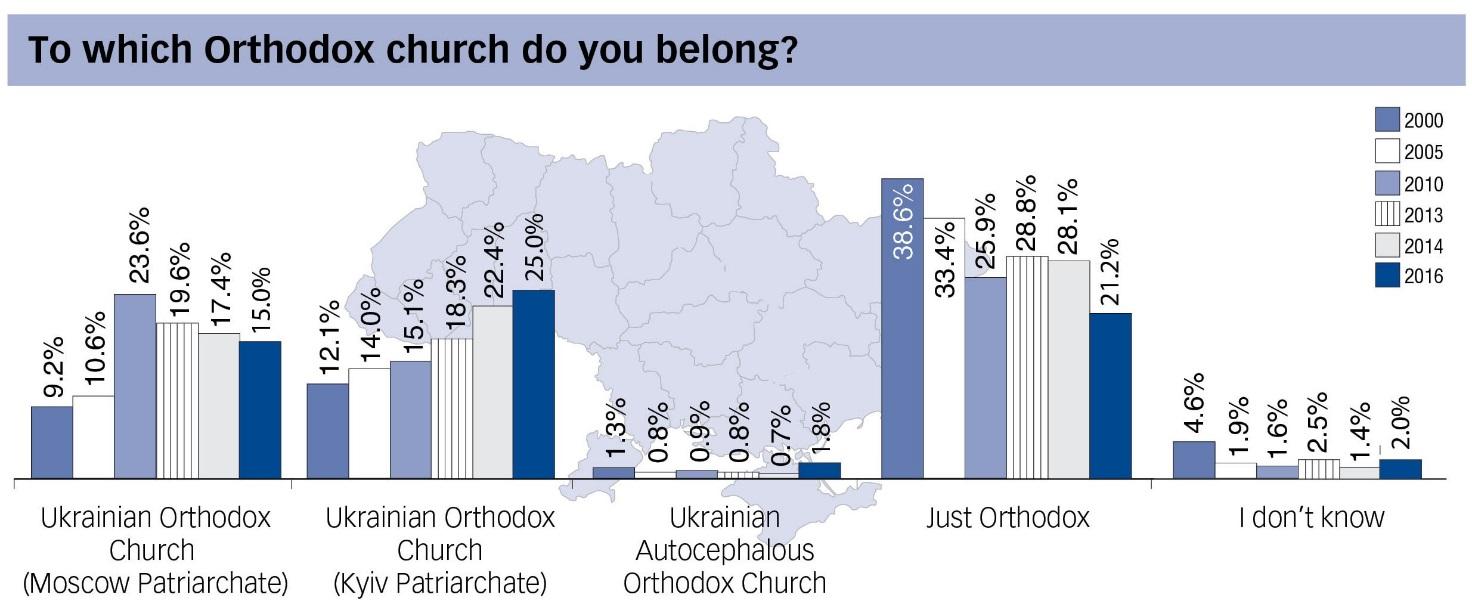

These three churches follow the same doctrine but are separate administrative entities. Although the UOC MP boasts the largest number of parishes and dioceses (12,064 parishes vs 4,807 of the UOC KP and 1,048 of the UAOC), its number of faithful has been dropping rapidly. According to the latest Razukov poll in 2018, 28.7% Ukrainians said they belonged to UOC KP (8.7 mn people in absolute numbers), 12.8% – to UOC MP (3.8 mn people). A significant number of people – 23.4% – said they were “just orthodox” (7.5 mn people), without identifying with a concrete confession.

So what happened in Istanbul?

The Synod made several decisions (our comments are in italics):

- confirmed that it would indeed grant Autocephaly to the Church of Ukraine – but did not say when;

- reestablished a Stavropegion of the Ecumenical Patriarch in Kyiv. A Stavropegion is an autonomous Orthodox Church unit (church, monastery, or union) subordinated not to the local hierarchs, but directly to the Ecumenical Patriarch and enjoying special rights – a representative center of sorts. The Ecumenical Patriarch established such Stavropegia before 1686 after which the Moscow Patriarch acquired this right. There are currently no Stavropegia of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Ukraine, so it is not quite clear what the decision refers to. Perhaps it is laying the ground for the future establishment of such Stavropegia;

- lifted the anathemas that the UOC MP placed on the leaders of UOC KP and UAOC, Filaret and Makariy and restore them in their hierarchical ranks, which means that as of 11 October, the faithful of these two churches which were hereto considered “uncanonical” and illegitimate, are now a part of the Orthodox Christian family.

Canonical territories of the autocephalous Orthodox Churches. Photo: orthodoxwiki.org, click to expand Here, the Ecumenical Patriarch as the higher-standing “first among equals” used his right to consider appeals by members of other churches, in this case – by Filaret and Makariy. Although rare now, this right was widely used in the first millennia of Christianity;

- revoked its 1686 Synodal Letter to give the Patriarch of Moscow “management rights” over the Kyiv Metropoly, including the ordainment of the Metropolitan of Kyiv. Formally, the Russian Orthodox Church violated the conditions of that letter – that the UOC MP would “commemorate the Ecumenical Patriarch as the First Hierarch at any celebration, proclaiming and affirming his canonical dependence to the Mother Church of Constantinople.” Instead, they commemorate the Moscow Patriarch;

- called upon all sides to refrain from force and violence. An important detail – tensions between churches are rising, and the UOC MP has started ringing (to this moment, false) alarms that Ukrainian nationalists had being seizing its property.

What did these decisions change?

According to Archimandrite Cyril Hovorun, PhD, Senior Lecturer at Stockholm School of Theology, they are preliminary decisions preparing the soil for the next steps – for the Ecumenical Patriarchate to plant the Autocephalous Church in Ukraine. They reinstated the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Ukraine and the status quo which existed up to 1686:

“It was a historical event. In the modern political life, you don’t often see decisions which correspond to events three-four-five centuries ago. But with the Church, this is the case, and yesterday’s decision of the Ecumenical Patriarch goes back to events of the 17th century.

The rationale for this sequence of steps is the following. If Constantinople granted autocephaly to the Ukrainian churches as they are now, there would be many reservations and concerns from other [autocephalous] Churches, and problems with the reception of the Ukrainian autocephaly from them. But if Constantinople grants full autocephaly to its own structure in Ukraine, there will be much less reservations about this.”

This decision is especially important given that Moscow had contested Constantinople’s right to decide on an autocephaly of the Ukrainian Church, arguing that Ukraine “constitutes the canonical territory of the Patriarchate of Moscow” and that, consequently, such an act on the part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate would comprise an “intervention” into a foreign ecclesiastical jurisdiction. Two weeks before the Synod in Istanbul, the Ecumenical Patriarchate had published a detailed historical note with convincing proof for its historical jurisdiction over the Kyiv Metropoly, apparently providing the conceptual base for the decision of the Synod. Moscow had not provided an answer to this note.

Meanwhile, religious scientist and professor Yuriy Chornomorets believes that the Ecumenical Patriarchate’s decision lays the ground for the unification of the three Orthodox churches in Ukraine, and will put the UOC MP to the test:

“Constantinople’s canonical rehabilitation of Patriarch Filaret gives Ukrainian bishops of the three jurisdictions a chance to unite. Will they use this chance? It’s obvious that not all the bishops of the UOC MP will join the unifying processes. So, this church will still function, but probably have its name changed to ‘Russian Orthodox Church’ and will significantly lose its influence on society, politics, faithful. This loss of influence has already happened over these four years [since Euromaidan – Ed]. This church starting from September 2014 has taken extremely conservative and pro-Russian positions, has isolated itself from society, from other churches. In 2017, the Bishops’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church had significantly curtailed the rights of the UOC MP by changes in the statute of the Russian Orthodox Church. Today, the bishops and priests of the UOC MP are placed before the need to decide: either to follow the canons, which require creating an autocephalous church headed by its own patriarch or remain subjugated to the Moscow Patriarch. This is a simple decision, and I think we will soon see how many bishops of the UOC MP are really bishops, and how many are pro-Russian politicians in church robes.”

What was Moscow’s reaction?

Vladimir Legoyda, head of the Moscow Patriarchate’s media and social relations department, stated that the Ecumenical Patriarchate Synod’s decision constituted an “unprecedented anti-canonical action, an attempt to destroy the foundations of the Orthodox canonical system.” On 15 October, the Russian Orthodox Church will convene its Synod in Minsk, Belarus, where it will give an answer to Constantinople’s actions. Possibly, this Synod will announce that the Russian Orthodox Church will severe its Eucharistic communion with Constantinople (or severe diplomatic ties, when translated from churchspeak), as Aleksandr Volkov, spokesman for Moscow Patriarch Kirill suggested.

Telling of the Orthodox Church’s role in Russian geopolitics, on 12 October Russian President Vladimir Putin convened an extraordinary meeting of the National Security and Defense Council, where the “situation of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine” was discussed. This is a revealing slip of the tongue, since to assuage Ukrainians, the UOC MP has been insisting it is independent of Moscow and in no way the “Russian Church in Ukraine.” Meanwhile, the UOC MP stated that despite the decisions of the Synod on 11 October, it still doesn’t recognize the UOC KP, UAPC, and the Stavropegia announced by the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

Moscow has attempted to foil Constantinople’s plan from the start, attempting to persuade leaders of other autonomous Churches to disapprove of Ukraine’s Church independence, but succeeded only with the Serbian Church. As well, the Russian Orthodox Church has even compared the granting of an independent church to Ukraine to the schism between the Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches in 1054. But if the Russian Orthodox Church breaks ties with Constantinople, other Orthodox Churches are unlikely to follow in Moscow’s steps, thinks Cyril Hovorun.

“Even if Moscow decides to break eucharistic relations with Constantinople, the other churches in my opinion are not going to follow this attitude. They will keep their relations with both Moscow and Constantinople and a global schism in the Orthodox Church will be prevented.”

Religious studies expert Viacheslav Horshkov in his turn considers Moscow is too weak against the rest of the Orthodox world to cause any significant damage.

“They lately haven’t given any theological argument against Constantinople’s actions. If they go into a schism, they will marginalize themselves. Let’s see how long they will last. There will be no ‘largest schism since 1054,’ the scale is insufficient. Moscow attempts to prove that it’s a very Orthodox country, but really it isn’t. Spirituality is a concrete thing that can be measured. This is first and foremost a measure of love for people. And everyone knows how Moscow treats human dignity.”

Why is the Ecumenical Patriarch doing all this in the first place?

When the Ecumenical Patriarchate had its jurisdiction in Ukraine, it passed the Ukrainian church to the rule of Moscow in 1686 under several conditions. Those conditions were not kept, and on 11 October the Ecumenical Patriarchate revoked this decision. This is the formal reason for Constantinople’s actions.

Another reason is the inability of the UOC MP to solve the problem of the schism on its territory over nearly 30 years. In recent years, the number of self-reported Orthodox faithful in the UOC KP and UAOC grew to be roughly twice larger than those of UOC MP, meaning that most Orthodox Christians in Ukraine were formally schismatic. Apparently, Constantinople decided that Moscow isn’t interested in finding a solution – and rightfully so.

(Note: percentages are from the total population of Ukraine, not from Ukrainian Orthodox Christians)

Yet another reason is church geopolitics, namely the conflict between Moscow and Constantinople. The Russian Orthodox Church with its reported 150 mn of Orthodox faithful regularly challenges the authority of the Ecumenical Patriarch, who bears the title of “first among equals” but after the fall of Constantinople and the Byzantine empire had his jurisdiction severely curtailed. In 2016, Moscow had ignored and attempted to foil the long-awaited Great Orthodox Council, which Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew considers his life achievement. As the UOC MP makes up for roughly one-third of the Russian Orthodox Church’s 30 675 parishes (as of 2013), Ukraine’s church independence would deal a severe blow for the Moscow Church’s authority – and geopolitical influence.

One more reason for Ukraine’s church question becoming so acute after 2014 is the Russian Orthodox Church’s ideological support for Russian politics. Had the Moscow Patriarchate not supported the lie about a “civil war” in Ukraine, approved of the Russian occupation of Crimea, and insisted on the old imperial illusion of Russians and Ukrainians being “brotherly nations,” the religious status quo in Ukraine could have lingered for many more years. UOC MP’s tacit support for Russian narratives used in its undeclared war against Ukraine and President Poroshenko’s scramble to boost his chances of being reelected in 2019 were the reason for Ukraine’s official appeal to the Ecumenical Patriarch, which set the gears of autocephaly in motion in Istanbul.

What will this new Ukrainian Orthodox Church look like? Who will be in charge of it?

At present, it’s not entirely clear what church structure in Ukraine is affected by the historic reinstatement of Constantinople’s jurisdiction over the Kyiv Metropoly. According to Cyril Hovorun, the closest structure in Ukraine is the UOC MP – because it is the only canonical church in Ukraine and because it is subjugated to Moscow:

“If the law of the church is to be enforced strictly in the wake of the decision of Constantinople, then the UOC MP should begin commemorating the Ecumenical patriarch in its liturgies and should affiliate itself with the Ecumenical Patriarchate from 11 October on.”

As it’s unlikely that UOC MP would do that, Constantinople’s decision will benefit other jurisdictions in Ukraine – the UOC KP and UAOC, which will have to effectively dismantle their own administrative structures and set up a new Church, which will receive the Tomos of autocephaly.

The UOC KP has already announced plans to hold a Council, which will convene bishops of the UOC KP, UAOC, and those of UOC MP who appealed to the Ecumenical Patriarch to grant a Tomos. This Council will elect a leader for the new Church.

Will the UOC MP join this new united Orthodox Church?

At present, it’s reasonable to assume that the UOC KP and UAOC will join the new Church in full numbers, says Cyril Hovorun. But it’s impossible to predict how many UOC MP will join the cause:

“I suggest that at the initial stage there will be a few of them, but as they see that the new structure is stable and functioning, more and more will join the new Church. There is a good chance that most of the UOC MP will eventually join the new church.”

Meanwhile, UOC MP priest Petro Zuiev says that in the likely scenario that the current UOC KP leader, 89-year old Patriarch Filaret, is elected to head the new Church, the majority of the UOC MP parishes could remain in the Moscow Patriarchate:

“The Russian Orthodox Church propaganda has throughout 26 years made Filaret a demon. And even though Filaret as a personality is much more pious than many Russian Orthodox Church bishops, he remains the ‘perpetrator of the schism’ for a significant part of the priests and faithful of the UOC MP.”

Taking this into account, it’s possible that the majority of UOC MP parishes will join the United Church only after Filaret’s successor takes the throne, says Zuiev.

Right now it’s unclear which part of the UOC MP will join the new Church. 10 out of 90 UOC MP bishops signed the appeal for autocephaly to the Ecumenical Patriarch – only 11%. But separate priests could join even if their bishops don’t, says Zuiev.

What will Church Autocephaly change in Ukraine – and beyond?

There will be several outcomes. For Ukrainian Orthodoxy:

According to Viacheslav Horshkov, the main result will be that Ukrainian Orthodoxy will achieve complete subjectivity:

“We now have the possibility to build relations with other Churches and develop our church life not on the imperial model. This is a colossal opportunity for the modernization of the Church.”

Cyril Hovorun hopes that church independence will benefit the people:

“Because the main purpose of the whole enterprise is to feel better, to go to the church where they feel well, where they don’t have any concern for anything which will contradict their conscience. Those people who have suffered for many years will join in full communion with the rest of the Orthodox Church, and this will be an important achievement. There will be a downside of this process – tensions are sure to arise between communities and inside communities. There may be an outbreak of violence, but it is up to the state to prevent such outbreaks. The Ecumenical Patriarch particularly stressed the peaceful merger of communities into the new church. And I think it was a very important point in this decision of Constantinople.”

Apart from provocations and tensions, the creation of the Ukrainian Church could carry an unexpected downside: this new Church could gain some qualities of a de-facto state Church like the Russian Orthodox Church. Cyril Hovorun:

“This could happen because the people [in Russia and Ukraine – Ed] are the same. And what should be paid attention to even more than the Tomos itself is what kind of quality of Church it will be. The issue of the Ukrainian Church should not be about quantity of independence, it should be about the quality of people’s participation, accountability, prayer, spiritual life. The Tomos cannot secure this state. An autocephaly is not a panacea to all the diseases and problems that the Orthodox community in Ukraine faces.

So, the Tomos is one opportunity for the Church to improve, but it is not something which will substitute the effort of the people of the Church to make their participation in Christian life more meaningful.”

For Ukrainian politics: a new United Church will give a much-needed boost to Poroshenko’s electoral campaign. The incumbent president has already started using the topic actively in numerous billboards around the country. However, the upcoming structural changes to the existing churches, and especially the sensitive question of church property, are sure to generate real and imaginary tensions. The UOC MP has previously falsely accused Ukrainian nationalists of attacking its property and is expected to continue doing this, casting itself as the victim. However, in a recent interview, UOC KP Patriarch Filaret hints at the forceful appropriation of major monasteries, or Lavras, from the UOC MP, causing anxiety among UOC MP believers. Therefore, Constantinople’s appeal to all sides to refrain from violence is especially meaningful.

Geopolitically speaking, an independent Ukrainian church will be a visible symbol of the fiasco of Putin’s post-Soviet neoimperialism. Russia’s reactions to Ukraine’s new Church is likely to lead to the increased self-isolation of the Russian Orthodox Church and loss of significance in the global religious arena. Theologian Paul Gavrilyuk writes:

“Numerically, the Moscow Patriarchate will eventually lose thousands of parishes. In ten years, we will no longer have Moscow/ Constantinople axis as the only major power struggle within worldwide Orthodoxy. Rather, we will have Constantinople as a soft power hovering over the three main churches with considerable numbers: Moscow (still the largest, contrary to some Ukrainian enthusiasts); Kyiv as a close second; and Bucharest as a very close third (19 million population, higher percentage of believers than in Ukraine or Russia). I predict that in this scheme of things there is a real potential for the Bucharest leadership because unlike Belgrade, it has not received multi-million euro gifts from Moscow; unlike Kyiv, it does not owe its recent legitimacy to Constantinople… Short-term all of this bids trouble; long-term, today’s move will have the implications of significantly curtailing Moscow’s ideological hold on Eastern Europe.”

However, the loss of imperial status of this church can also provoke its renewal: greater independence from the state, strengthening the role of the laity, and a more democratic form of church governance. And for Ukraine, it means severing yet another link connecting it with Russia – an unexpected outcome of Russia’s war against Ukraine. According to Gavrilyuk:

“Putin’s war in Ukraine may have gained Crimea by deceit, denial, and violence; it may have destroyed the infrastructure of a large part of Eastern Ukraine. But the long-term effect of the war was to push Ukraine away from Russia culturally and economically, and with that, the collateral damage to Russia’s own economic interest in Europe has been considerable. Putin has attempted to re-colonize Ukraine; in reality, he has continued to impoverish his own people and, paradoxically, will leave the wanna-be-empire even more vulnerable to the economic colonization by China. It does not take a ‘Slavophile’ to understand this point.

Long-term, Constantinople’s historic act will bring greater peace to Europe.”

Read also:

- Why Ukraine needs a free and recognized Orthodox Church

- Waiting for Constantinople’s historical decision on Church autocephaly in Ukraine

- Inside Ukraine’s appeal for Church autocephaly

- The Great Orthodox Council ended. Now what for Ukraine?