On 13 June 2023, Ukrainian sniper, Maidan activist, and photojournalist Roman Chornomaz, call sign “Corsair,” died on the frontlines near Bakhmut.

Roman was the third generation of his family to struggle against Russian imperialism. However, unlike his father and grandfather, who got off with prison time, he died in battle for his right to live in a free Ukraine.

Roman Chornomaz was an active participant in Ukraine’s 2014 Euromaidan Revolution. On 20 February 2014, he was at the forefront on vul. Instytutska, where he documented the shooting of unarmed protesters by the riot police of the pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych.

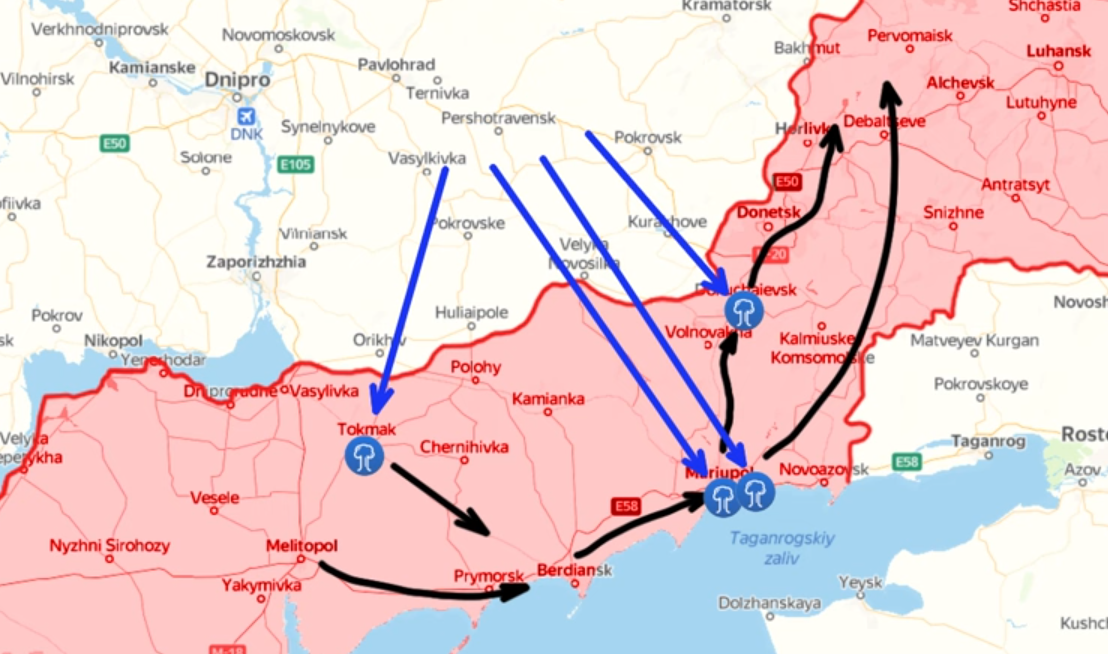

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022, Roman volunteered to join the army despite serious health problems. As a sniper with the Svoboda (Freedom) Battalion of the Rubizh Rapid Reaction Brigade of Ukraine’s National Guard, he defended Ukraine on the frontlines for over a year. He was engaged in fierce battles in Sievierodonetsk, Zaitseve, and Bakhmut.

Dissidence and civic activism – a family tradition

Born on 11 May 1976 in Uman, Cherkasy Oblast, Roman Chornomaz came from a dissident intelligentsia family with patriotic roots.

His grandfather was a member of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which fought for an independent Ukraine, and was imprisoned under Polish, German, and Soviet rule; his great-grandfather a priest executed by the Bolsheviks in 1937.

Roman’s father, Bohdan Chornomaz, was a dissident and life-long activist who, during Soviet times, worked towards the dream of an independent Ukraine together with Viacheslav Chornovil, a national-democratic leader who forged Ukraine’s independence after spending 17 years in Soviet prison camps.

He was arrested in 1972, two days before his wedding, on charges of Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism, anti-Soviet propaganda, and agitation.

The formal reason was his reproduction and dissemination of dissident Ivan Dziuba's banned work “Internationalism or Russification," which challenged the Soviet Union's eradication of national identity as Soviet citizens were molded to become Russians.

“My father put up a huge reception tent in the village, slaughtered two pigs, and salted a barrel of fish. Everything was ready for the wedding. But the groom - Bohdan - was arrested two days before the event. We didn’t have cell phones in those days, so everyone came, even the musicians. So, the wedding took place without the groom. The KGB told me to tell everyone he’d been in an accident,” says Roman’s mother, Tetiana, in an interview with Hromadske.

Bohdan Chornomaz served three years in the harshest Soviet penal camps of Siberia, was rehabilitated in 1991, and later became a historian researching Ukraine’s national liberation movement under Soviet rule.

Roman’s mother, Tetiana Chornomaz, is a prominent volunteer and public figure. She edited the first uncensored anti-communist newspaper “Chervona Kalyna” and worked as a journalist for Radio Liberty.

“My son was an ordinary boy from an ordinary family. Well, maybe he had not so very ordinary parents who decided that the main thing in our lives was to defend our land, to fight for our land, to have our own state… There was nothing Soviet in our home. My parents didn’t send me to kindergarten, and I didn’t send Roman or Sofiya either. I didn’t want them to recite Lenin’s verses or learn stories about Ded Moroz [Soviet Father Frost-ed],” says Tetiana.

Roman’s sister, Sofiya Chornomaz-Lytvynenko, recalls that their parents always took them to pro-Ukrainian rallies and protests. The children held the flags and banners because, at that time, the police were not allowed to attack children.

Though educated as a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature, Roman Chornomaz spent most of his career in journalism as a photojournalist was published widely in Ukraine and foreign media. He lived and worked in Kyiv before returning to his native Uman, where he continued as a freelancer and farmer, growing vegetables and experimenting with new crop production technologies.

“I thought 40 was the right age to settle down into a quieter lifestyle, contrasting my previous one. I was constantly traveling around the country as a photojournalist, visited all oblasts and district centers, and a huge number of villages,” Roman said in an interview. “But the war would not allow me to sit still.”

Roman jokingly described himself as “a shaggy-haired guy who likes going to festivals to take pictures.” In reality, he was a profound, intelligent, and complex figure who combined classical liberal values with nationalist ideas.

He advocated for restoring the rights of the Ukrainian language, eradicated throughout centuries of Russian linguistic repression, and also for the establishment of an Orthodox Church independent of Moscow.

The call of Maidan

An active participant in the Euromaidan Revolution, which saw Ukrainians revolt against then-president Yanukovych reneging on his pro-EU pledge under Moscow pressure, Roman Chornomaz took part in clashes with the Berkut riot police.

After the bloody crackdown on 18 February, when government snipers shot dead dozens of unarmed protesters, Roman called upon Ukrainians to get involved and stand up against repression on his Facebook page.

“I’m in Kyiv now after walking along the Maidan frontlines. I’m struggling to find words to describe what I saw. There are no words fit for this. It’s all fucked up. Either it’s us or them. Come on, come to Kyiv now! Break through the roadblocks and get here! The Maidan is full of people and hopefully stays that way until morning. I’m exhausted, so I’m going to sleep a few hours in a safe house, but God save us! If you go to work tomorrow as if nothing’s happened, you are slaves - stupid robots and blind horses.”

Euromaidan photos by Roman Chornomaz

On 20 February 2014, Roman was in central Kyiv, documenting the shooting of unarmed protesters as well as the heroism of Euromaidan activists risking their lives to rescue wounded comrades.

Photographer-turned-sniper deploys to eastern Ukraine

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, Roman volunteered for the army despite serious health problems. With his malady, he could have left the country but chose to stay and fight.

“Sitting around at home is not an option, reading the news and being constantly afraid. You might say it’s [resisting - Ed] in our blood,” he said.

As a member of the Svoboda Battalion of the Rubizh Rapid Response Brigade in Ukraine’s National Guard, he defended Ukraine on the frontlines for over a year, enduring fierce battles in Sievierodonetsk, Zaitseve and Bakhmut.

In January 2023, he was wounded in combat near Bakhmut, hit in the arm by shrapnel with additional contusions.

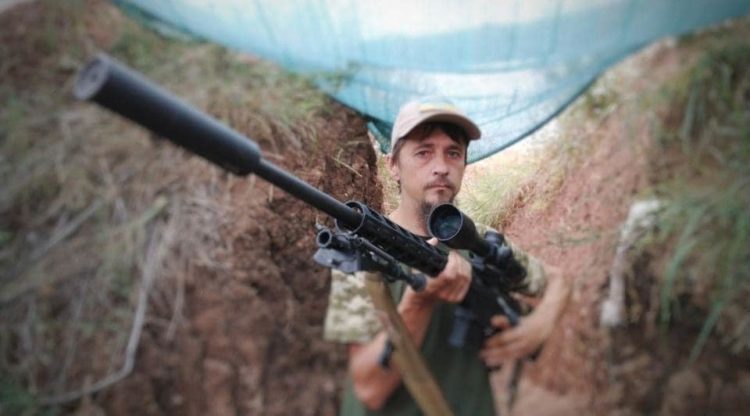

Roman chose the sniper specialty, demonstrating a natural aptitude for this skill. He raised funds to purchase his equipment and sniper rifle, which he named “Witch,” and completed rigorous training.

“It turns out this job suits me well, and I picked it up quickly. As a photographer, I understand optics and how they work. I also remember physics class and understand bullet ballistics and flight paths. Of course, there are many nuances to learn, but with motivation and skills, you can master anything.”

He pointed out that snipering was an intellectual job requiring precise calculation. A sniper must be able to observe, draft firing maps, and identify enemy positions. Snipers are a cross between a commander and an infantryman, with great risks involved. There were many cases where the enemy covered an entire area with Grad rockets trying to take out a lone sniper.

His sister Sofiya notes that Roman had a lot of endurance, and was very patient and focused. He was not hot-headed but rather cold and calculating, as his company commander said. He reacted very calmly to everything.

Roman repeatedly emphasized the importance of combat soldiers learning useful specialties beyond basic shooting:

“Machine gunners alone aren’t enough. To keep the enemy at bay, we need more - mortar crews, artillery, tankers, drone operators, drivers - specialists who can do real damage.”

Roman gained combat experience in Sievierodonetsk, enduring heavy fighting and constant massive shelling. He and his comrades-in-arms held an entire building for a month, where every morning, an enemy tank would arrive and destroy parts of the structure. When the Ukrainian unit retreated, almost nothing was left of the ten-story residence.

“I thought I’d take lots of photos and videos from the front, but frankly, there’s almost no time or energy for that. There’s constant shelling; I must run to a firing position and shoot back. When the enemy attacks, you can’t stop to film even if you want to. And when things calm down, you just want to rest, eat, and sleep,” he told Svoboda Weekly.

Death on the outskirts of Bakhmut

Between battles, his battalion would train at military facilities where Roman eagerly learned new skills. In late 2022, his unit relocated to Bakhmut.

“The first thing that surprised me is how freely the Russians walked the fields and tree lines near Bakhmut. I watched them through my thermal sight and got to work. Only after a few days of attrition did they learn to hide.”

In February 2023, he wrote online: “The past three months at ground zero by Bakhmut have been damn hard - cold, damp, fog, snow, mud. That’s the real enemy; that’s what wears you down morally and physically. I’ll hate planted fields and dead blackened sunflowers for the rest of my life. So many wonderful people I knew died in those damn fields, far too many. It always makes me sick when they say ‘our losses were insignificant.’ There’s no such thing as small losses. Every death hurts beyond measure.”

In a video interview with NV, he continued his thoughts about war: “I used to think that hell should smell like sulfur. Not at all. It actually smells like live fire, burnt objects, scorched buildings. That’s the smell of hell.”

Roman Chornomaz died on 13 June 2023 when an enemy missile struck the armored vehicle transporting his unit near Bakhmut. It took two days to evacuate his body from the battlefield. The family then had to wait two months for the DNA testing results. Roman was buried on 31 August 2023 in the Alley of Heroes of the Sofiyivska Slobidka Cemetery in Uman, Cherkasy Oblast.

Tetiana Chornomaz affirms that nothing and no one could break her son’s spirit… and the same is true of Ukrainian defenders now.

“I’m proud of my son, his spirit and desire to go to war and defend his country. We don’t want to be different; we want to be Ukrainian. When my son was no more, I sat there and thought: ‘My Roman gave his life so that I could live here in my house, so I wouldn’t have to wander around train stations in Warsaw, Prague or some other countries. This is my home.”

Related:

- "I chewed that mouse between my teeth." Ukrainian POW details torture, starvation in Russian camps

- Ukrainian soldier battles exhaustion in 14-hour swim for survival

- “Stopping the modern Hitler”: snipers hold the line in Ukraine’s battle for survival

- Defiant woman judge endures Russian captivity, torture and abuse

- Warrior Yaryna enlists to carry on the legacy of her beloved men

- Tribute to Maksym Kryvtsov: poet warrior killed defending Ukraine