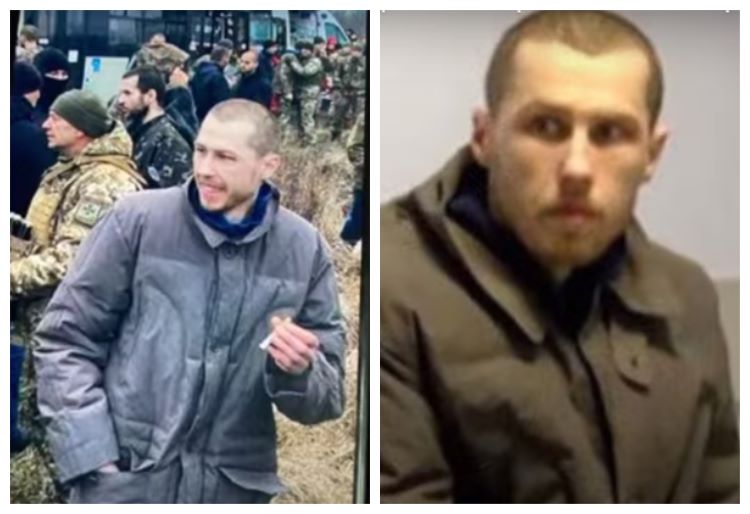

Oleksiy Anulia, a 30-year-old kickboxing champion from Chernihiv, was one of the 140 Ukrainian soldiers who returned from Russian captivity on 31 December 2022. After a long period of medical treatment and rehabilitation, he reveals his ordeal of torture, brutality, electric shocks and starvation.

Russian forces invade Chernihiv Oblast

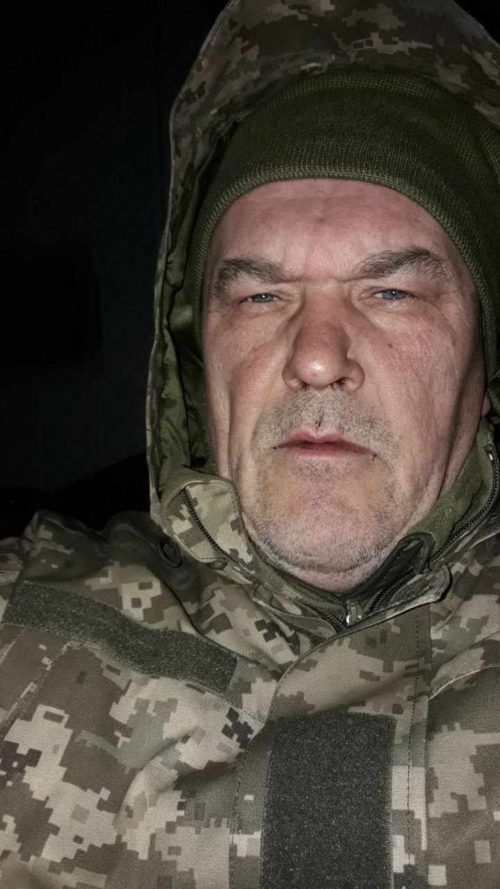

On the day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Oleksiy and his father, Yuriy, grabbed their rifles and joined the Ukrainian Army together. They were deployed to Lukashivka, a village near Chernihiv, where they faced a massive attack by the Russian forces on 9 March.

“We were 140 against 5,000 Russians, 35 tanks and armoured cover vehicles. We had nothing to shoot at them with; we were only given one NLAW (Swedish-British anti-tank system),” Oleksiy says in an interview with Texty.

Fighting ensued as small groups of Ukrainians struggled to halt the invaders. Oleksiy was wounded by shrapnel and concussed by an explosion. As Russian tanks entered his village, Oleksiy believed death had arrived. He crawled out of the house and ran to the nearby forest.

“I sat there watching the tanks roll in. The first turned its turret directly at me. I thought – this is how my life ends…that’s it,” he recounts in an interview with Suspilne Chernihiv.

Severely wounded with ears ringing from the blasts, Oleksiy considered ending things quickly by shooting himself under the chin with his machine gun. Instead, he lay there for 12 hours trying to regain strength and clarity.

However, he was betrayed by a local who informed the Russians of his whereabouts. There was nowhere left to run, so he buried his weapon, documents and chevrons, left his hideout, and surrendered to four Russian soldiers – Buryats, ethnic Mongols from southeastern Siberia, who handed him over to the Russian army command.

“They searched me and took all my valuables: German boots, a belt with the inscription ‘Pentagon’, a knife, a Japanese Casio watch,” he says.

Oleksiy was immediately taken to a torture chamber, where he endured brutal treatment and interrogation. They also tried to unlock his touchscreen phone, which had a square root √ as a password; the Russian soldiers were unable to understand the process, so they threatened to cut off his finger and use his thumbprint, but they did not succeed.

The Ukrainian fighter was interrogated by a lieutenant general, who had a laptop with his father’s biography. The general knew everything about his father Yuriy and his past services in the Soviet army, even the secret parts.

Oleksiy was then transferred to Ripkyne District, near the Belarusian border and thrown into a torture chamber in an abandoned building. Next to it stood a KAMAZ truck, where the Russian troops burned the bodies of the dead – both Russians and Ukrainians, civilians and soldiers.

Interrogations and beatings

Interrogations and beatings began… The most aggressive was a Russian soldier from the Caucasus region who enjoyed raping prisoners.

“It was normal for them to satisfy their sexual needs in this way. With me was a 20-year-old Ukrainian guy who’d been raped at a checkpoint by six Russian soldiers in turn, and his parents were in the car next to him, forced to watch.”

The Russians ordered Oleksiy to undress, tied his hands and strung him up with the intention of raping him. He hung from the ceiling by his arms for six days but was miraculously saved when the Ukrainian artillery started firing intensely nearby.

The prisoners were then transported to a detention centre near Kursk, where Oleksiy spent 40 days, enduring beatings and mental abuse.

“They looked through everything, and read all my correspondence. If I couldn’t remember the passwords, they beat me vigorously. It was important for them to track down who participated in the Maidan or other protests on the Khreshchatyk, against the Moscow Patriarchate, for the Tomos, who attended the rallies for Poroshenko and Zelenskyy, who had relatives in Russia. If they found someone who had been on the Maidan, they killed him,” he reveals.

On 5 May, the prisoners were sent by plane to Tula, and from there to the Donetsk detention centre.

Starved and beaten daily without cause, Oleksiy describes the trauma that Ukrainian prisoners were forced to endure. They beat him constantly with sticks, truncheons and stun guns. Oleksiy had a hard time walking as his foot had begun to rot. His head, arms, legs and anus were bleeding profusely. The women prisoners were also brutalized.

“I used to weigh 102 kilos, but in captivity, I lost 40 kg and six cm in height, down to 186 cm. My ribs and fingers were broken. They cut the tendons in my thumb, saying ‘You were shooting our soldiers with this finger’… There was no compassion – neither for me nor for the younger conscripts aged 18-19. They scratched the letter Z with a nail on their cheeks to distinguish them from the contract soldiers,” he testifies.

Oleksiy attributes his resilience and survival to his strong physical condition. In civilian life, he practised kickboxing every day, ran daily and exercised at the gym. But now, despite being an athlete who could previously do 35 pull-ups, his health deteriorated rapidly. He recalls being forced to squat 500-1000 times nightly alongside wounded prisoners. The only woman prisoner he saw was a 23-year-old Ukrainian language teacher, psychologically shattered. The other prisoners were mostly civilians.

For no reason, the Russians threw Oleksiy into a punishment cell. The sewage system was leaking, and urine and faeces flowed into his cell. The stench was nauseating. Detailing the brutal conditions, he says, “We were allowed to go to the toilet once a day, for one minute…The rest of the time, we had to stand 18 hours a day.” They were ordered to spread their fingers wide open and motionless. The guards made sure that no one closed their eyes. If anyone moved, the door would open, the guards would come in, drag the prisoner out into the corridor and beat him savagely with their boots or truncheons.

CCTV cameras monitored their every move, and the slightest movement was “rewarded” with beatings.

Yet even in darkness, Oleksiy maintained a flicker of humanity. He reminisced about his childhood days, his father and mother, and life in the country.

“In the cell, for some reason, I remembered my childhood, when I was four or five years old and playing with cars or walking with my dad.”

Freed medic: Russians raped girls as young as 14 in Ukraine prisons

Solitary confinement

The cruelty continued in solitary confinement – a damp, mouldy basement room designed to break a person’s morale. According to Russian law, a person can be confined for 5-7 days. But Oleksiy spent 108 days in solitary. A fellow prisoner, a Ukrainian officer – 136 days.

Alongside beatings, the abuse aimed to dehumanize. Prisoners had to shout loudly in their cells on command, performing rituals like shouting insults, jumping, and squatting endlessly.

“We were ordered to shout: Zelensky is a f**ker, Biden is a f**ker, Stoltenberg is a f**ker, Putin is our president!”

Hunger bordering on starvation

Besides endless beating and physical and mental abuse, food deprivation and starvation were part of the daily ritual

For breakfast, the prisoners were given a piece of bread and two spoons of groats and water in which the Russians had boiled their buckwheat or rice. For lunch, there was a watery soup with cabbage, and for dinner, again, chaff mixed with water. Sometimes, the prisoners received boiled fish intestines with the heads. Oleksiy ate everything. Once he got a piece of boiled onion. He chewed on it for a long time, making it last, enjoying the taste and flavour.

One day, Oleksiy brought an earthworm in from the walk in the prison yard. He wrapped it in a rag, put it in the cistern and forgot about it. A week later, he took it out, and there was a whole brood of squirming worms! That was Oleksiy’s first protein in a long time. He ate them all and admits that since his captivity, he has never enjoyed chocolate with as much pleasure as those worms.

One day, starved and desperate, Oleksiy finally caught a mouse that he had been stalking for several weeks, but the warders saw him moving around in the cell, which was forbidden.

“To prevent the mouse from escaping, I put it in my mouth. I pressed it down with my teeth so that it couldn’t run into my throat. It gnawed at my palate, bit through my tongue…I was holding the mouse as tightly as I could between my teeth,” he recounts.

The guards began beating him savagely, aiming at his right kidney. They pounded savagely and all the while, Oleksiy clenched his lips, holding the mouse firmly between his teeth. Blood flowed from the mouse bite in his mouth, and the guards suddenly thought that they may have damaged his kidney. The torture stopped.

“I crawled back into the cell through the faeces on the floor… I barely had the strength to stand up, but my heart was full of joy. I didn’t feel any pain. I realized subconsciously that I was chewing meat and it would help me live until the morning. My mouth tasted of blood and liver… Tufts of hair were stuck between my teeth. I spat out the mouse teeth. I chewed the tail for a long time; it was like chewing a hard piece of gum.”

No medical aid or treatment

There was little or no medical treatment in the penal colony, only intensifying injuries amid psychological torture. Medical visits and examinations were cursory and medical complaints were met with more beatings. The blankets and bed were infested with lice.

The prisoners were taken to the bathhouse once a week and given a minute to wash. But the bathhouse was also another place of torture. The Russians would get drunk on that day, make the prisoners stand with their arms and legs apart and stun them with electric shocks on their wet bodies. They hit the prisoners on the spine with wooden mallets and rubber truncheons. Three vertebrae in Oleksiy’s spine were broken.

“My father was burnt alive…”

Oleksiy’s father, an experienced soldier, had not believed that war would come to Ukraine, often dismissing it as a joke. He died in Lukashivka after leading 40 people out of an encirclement, then returning to blow up several enemy tanks with a grenade launcher.

On that day, locals saw Russian soldiers capture him and four other Ukrainian soldiers. They witnessed the Russians torturing the captive soldiers inside the Lukashivka church before burning them alive.

They then dumped the burnt remains along a road between the neighbouring villages.

Searches eventually located the body of Oleksiy’s father, which DNA tests later confirmed. Originally buried in Nizhyn, his father’s remains were reburied over a year later at Chernihiv’s Yatsevo cemetery in late May 2023 after Lukashivka’s liberation enabled transporting the remains of the burnt dead collected from the roadside sites.

The prisoner exchange

Two weeks prior to the exchange in December, Oleksiy, for some strange reason, remembered the American song “Jingle Bells,” finding solace humming it as Russian officials repeatedly insisted he would not be freed.

Returning to his cell after yet another session of torture, he prepared to hang himself using a bed sheet.

“I already had a rolled-up sheet prepared, on which I planned to hang myself,” he admits. But a vision of his grandmother appeared, asking “Where are you going? You haven’t bought your children presents for the New Year yet.”

Guards witnessed him seemingly talking to himself via CCTV. Opening the cell, they proceeded to beat him forcefully again.

Of 192 Ukrainian detainees in that Russian prison on 28 December, only a few men including Oleksiy received orders to pack their belongings, potentially indicating a transfer or an exchange. Barely able to walk, he was dragged into a room, forced to strip naked, and beaten with truncheons.

The next day, only ten prisoners got into an old vehicle and then boarded a plane, knowing neither the reason nor the destination of their journey. The group flew to Kursk not knowing what awaited them.

On 31 December 2022 at 5 AM, nine names were called out. The men were packed into buses again and told that they would be executed. Reaching a point on the Russian border, near Sumy Oblast, Ukraine, they suddenly heard a Ukrainian voice saying “Hey guys, should heroes sit that way?”

As he took a drag on the first cigarette ever to touch his lips, Oleksiy listened to his wife Natalia’s voice in an emotional phone call once safely back in Ukraine on New Year’s Day 2023.

Rehabilitation

To close the chapter on his traumatic experience in Russian captivity, Oleksiy had to do one last thing – recuperate his assault rifle and documents from his Lukashivka hideout.

Oleksiy underwent ten months of medical rehabilitation – six in Ukraine spanning 16 hospitals plus a month in Israel and 99 days in Latvia, returning in early November 2023. Detailing the immense medical efforts needed to rebuild his life, the former prisoner shares his hope for the future.

“My brother, three years younger, is now at the front. My mother was left alone. In captivity, there was only one thing that made me happy: the thought of my son and daughter. Nowadays, many people say that it’s not the right time to have children. But I want to say that it’s the continuation of the family.”

The former prisoner learned that his eventual addition to the exchange group occurred thanks to a former colleague’s tireless advocacy, leveraging every possible Ukrainian and international connection until he succeeded in securing Oleksiy’s release.

Oleksiy Anulia knows that he survived thanks to friends and aid groups that worked tirelessly to free him from the hell of Russia’s penal colonies. He continues to heal, determined to expose Russia’s brutality and continue calling for justice.

RELATED:

- Russian torture chamber network in occupied Ukraine part of strategy to extinguish Ukrainian identity – lawyers

- Ukraine finds Russian torture chamber in Mykolaiv Oblast

- Ten torture chambers found in liberated Kharkiv oblast, six of them in Izium – Police

- Russian occupiers set up torture chamber in recently occupied Balakliia, Kharkiv Oblast

- Ukrainian ombudsman shocked by scale of torture chambers in Kherson Oblast

- “I never cried, I just screamed in pain.” Survivors of Russian torture chambers speak