We are currently experiencing a moment of decolonization in East European and Eurasian Studies that is becoming a new paradigm for this problematic field. I recently attended several conferences in the area, all of which had decolonization as a very prominent aspect.

Examples include the annual conferences of the Stockholm-based Centre for Baltic and East European Studies and the British Association of Slavonic and East European Studies in Glasgow. The conventions arranged by the US-based Association of Slavic, Eurasian, and East European Studies and Helsinki’s Alexanteri Institute are scheduled during the coming months, proclaiming decolonization as their main theme, too. Quite a remarkable consensus, isn’t it?

The two impulses behind decolonizing East European and Eurasian Studies

This decolonization buzz is a direct result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine—the field is trying to figure out where we went wrong, which is great. There are two main impulses behind this movement.

- The first impulse comes from scholars of Caucasus, Central Asia, and the indigenous nations of Russia. Inspired by the Ukrainian resistance, they also vocally empathize with it. And the decolonization theory as shaped by such luminaries as Frantz Fanon, Edward Said, Gayatri Spivak, and others from African and Asian experiences of colonialism, fits perfectly within the contexts of Siberia, Central Asia, and the Caucasus.

- The second impulse comes from what I would call Greater Eastern Europe. This ad-hoc definition includes Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova and has strong links to the Baltics, Poland, Central Europe, and the Balkans. This second impulse arose as a most direct reaction to the ongoing invasion of Ukraine—but, just like the first impulse, it has much longer historical roots.

The writings during the 1920s of Mykola Khvyliovy, who inspired the “away from Moscow” slogan, and Mykhailo Volobuyev, a Ukrainian economist who criticized Russian economic colonialism in his country, are just two examples.

The essence of their ideas has persisted in the ongoing postcolonial “moment” in Ukrainian literature and cultural studies that has lasted since the collapse of the Soviet Union. It has blossomed in the studies and essays by Marko Pavlyshyn, Tamara Hundorova, Mykola Riabchuk, Vitaly Chernetskyi, and others. They and scholars from Greater Eastern Europe, such as Ewa Thompson, developed the necessary perspective over the past 30 years.

These two different traditions—that of Caucasus, Central Asia, and indigenous nations of Russia and that of Greater Eastern Europe—deal with different situations and challenges. But they are still evoked by the same phenomenon, Russian imperialism, and their parallels are many, and the paradigm is roughly the same. Yet many of the problems they face are vastly different.

We are dealing with two different fields rather than one single unified field. Therefore, we must give up on the old field of “post-Sovietology” as we are dealing with different situations that require different approaches within the same decolonization movement. It is time to bury this corpse.

History that unites us

I admire solidarity and vibrant dialogue between the various fields that actually make up the Frankenstein of “Eurasian Studies.” This is the only way forward and the only way to really decolonize the old putrid monster of post-Sovietology. Great historical precedents of this solidarity exist.

Taras Shevchenko is known as Ukraine’s national poet, the one who can be credited with formulating the idea of modern Ukraine. Much less known is that he also pioneered anticolonial discourse in the Russian empire in his poem Caucasus. In it, he empathizes with Chechen freedom fighters and brushes the empire with a biblical prophet’s indignation. Notably, he decries the death of his friend killed in this colonial war as an officer in the Russian army. This loss does not make him bitter against the Chechens but rather against the empire.

This poem became part of the tsar’s police criminal case against him. As a result, he was condemned to 25 years of penal army service with a ban on writing, painting, and drawing. For a young urban artist and intellectual, it was a viciously harsh sentence supposed to break and neutralize him as a political threat.

Shevchenko was sent to an army unit stationed in Kazakhstan as part of the colonial force. The conditions were cruel but he managed to draw and write in secret. His poems and artworks expose the real ugly face of Russian colonialism in Central Asia.

For example, “The Stately Fist” shows a threatening refusal of a Russian official to give alms to two indigenous child beggars. Not only does it criticize the impoverishment and exploitation of the colonies, but also serves as a metaphor for the whole Russian power regime in the region.

Many decades later, one of the leading Orientalists from Eastern Europe was the Ukrainian scholar Ahatanhel Krymsky. Descended from Crimean Tatars, he became renowned as a linguist and historian who should not be classified as one of the Orientalists interested primarily in domination, such as those attacked by Edward Said.

Instead, Krymsky used his personal, intimate knowledge of realities and sources to show how Ukraine was shaped by its interaction with Turkish nations, Crimean Tatars, Ottomans, and peoples of Central Asia. He was also politically very progressive and anti-colonial.

In the 1920s, Krymsky was the major driving force in the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. At this time, the Academy in Kyiv and Tbilisi corresponded in French—surely, they could have done it in Russian but there was more to it than a simple snub. Their point was to dismantle the empire by bypassing the imperial center of Moscow and also by bypassing the imperial language. Instead, they chose to talk to each other directly, over the head of the resurgent imperial center, and using the international language of scholarship at the time.

I am just scratching the surface of common knowledge among educated Ukrainians, and there are many more examples like this. But they show how direct conversations among the peripheries challenge the empire.

Actually, this is my favorite definition of an empire coming from the Ukrainian American scholar Alexander Motyl: Empire severs links between the peripheries, making communication and interaction possible only via the imperial center.

This is why I am enthusiastic about the dialogue among scholars of all subaltern nations of the former Russian empire. Those long-standing historical precedents set the stage for our current decolonization in the 21st century. Now as then, Ukrainians, peoples of Caucasus, Central Asia, and Russia’s indigenous nations choose to come together in solidarity and support each other, communicating directly without any need for the imperial resources of Moscow or St. Petersburg.

Empire severs links between the peripheries, making communication and interaction possible only via the imperial center.

Alexander Motyl

History that divides us

There is also a different side to Ukraine’s story in the Russian empire. Let’s go back to Shevchenko’s friend killed in a colonial war, perhaps an unwilling victim (much like today’s “good Russian”) but still an invader and a colonizer. And there were much worse: real villains who served the empire.

Meet Gen. and Field Marshal Ivan Paskevich, of Cossack stock, who was a key figure in the colonization of Caucasus. He is also notorious for brutally repressing the 1831 Polish uprising and the 1848 Hungarian revolution. He was the Viceroy of Caucasus and Poland and was awarded the title of “prince” for his exploits.

Many people like him highlight the complex role of Ukraine in the Russian empire. As much as there was a constant subversion, there were also generations of Ukrainians serving it and building it. It was built with Ukrainian minds, hands, sweat, and blood. This is why Vitaly Chernetsky is right when he compares Ukraine with Scotland or Ireland in the British Empire: “A colony at home.”

Using colonized elites and masses is nothing new here. Scots and Irishmen were sent to colonize India, and Indians were sent to colonize Africa, all while their own native countries were being colonized. Divide et impera is the archetypal imperial motto from the archetypal empire of Rome.

Vitaly Chernetsky is right when he compares Ukraine with Scotland or Ireland in the British Empire: “A colony at home.”

Why do we need several fields instead of one?

Obviously, in order to disrupt the empire, we need to unite over those divisions and establish those direct ties and conversations between peripheries. But does this mean that we have to erase all divisions? Does it mean we have to continue living within the borders of the Russian empire as of 1913?

If we look at the borders of our field, we will see that the only way to define them consistently is “we study whomever was under the Russian rule in 1913”—except perhaps Finland. Nowhere has the empire of Romanovs survived as well as in the outline of our very field!

We are still the agents of “the imperial knowledge.” We still serve the empire that lies in its death throes in Bakhmut and Kherson. And if we look at the field deeper, we will see that there are differences.

As the complex case of Ukraine shows, its relation with the empire was very special. For a long time, roughly from after 1709 into the first half of the 19th century, the empire was a joint venture of Russian and Ukrainian elites. There is also a deeper layer to this.

Trending Now

Shevelov remarks that it was the imperial greed of the Grand Princes of Kyiv that fomented the rise of Moscow.

I will never tire of promoting a genial idea formulated in a footnote by George Shevelov, a great Ukrainian American linguist who was bullied and disparaged by none other than the star of the 20th-century humanities, Roman Jakobson. Considering phonological changes in the medieval dialects of Rus, Shevelov remarks that it was the imperial greed of the Grand Princes of Kyiv that fomented the rise of Moscow.

From this perspective, Moscow was an exploited colony of Kyiv’s empire that eventually rose against its metropolis, the mother of Ruthenian cities (or Rusian—not Russian!).

The Moscow polity razed the Kyiv polity in 1168, which ultimately led to the decline of Rus’. Gradually, Kyiv became an old empire suffering at the hands of its insurgent colony Moscow which has now built an empire of its own.

In Central Asia, Russians had a different approach. Rather than driven by envy, hatred, and lust for the prestige of its old colonizer Kyiv, Muscovites would move eastwards armed with the techniques of Western colonialism they were emulating. This was brilliantly parodied in Shevchenko’s “The Caucasus”:

“We’re civilized! And we set forth

To enlighten others,

To make them see the sun of truth...

Our blind, simple brothers!!

We'll show you everything! If but

Yourselves to us you’ll yield.

The grimmest prisons how to build,

How shackles forge of steel,

And how to wear them!”

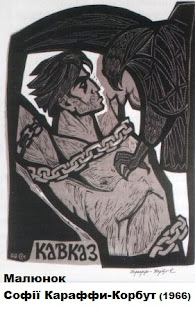

An illustration for Shevchenko’s “Caucasus” poem depicting Prometheus, a symbol of the immortal oppressed people, whose ribs are being picked by an eagle, symbolizing the Moscow Tsar-tormentors. Art by Sophia Karaffa-Korbut, 1966.

These specificities of the relationship between the Russian empire and each particular periphery have nothing to do with race or ethnicity but rather with history and how societies and cultures developed. There are of course differences in terms of social structures, religion, language, and many other areas.

All of this leads me to the final point. While we have a common task grounded in unconditional mutual sympathy and solidarity, do we have to work towards this task within the confines of the same kolkhoz field that suspiciously overlaps with the borders of Romanov’s “prison of nations”? Will we not be better served by having independent fields of our own while fostering intensive dialogue and collaboration among them?

Russian Studies and the risk of decolonization

So what about the study of Russia proper? One of my observations is that while we see these two separate areas of greater Eastern Europe studies and greater Central Asia/Caucasus studies arise in solidarity and come into a vibrant dialogue with each other, Russian Studies departments, in a narrower sense, do not seem willing to change and appear to be self-marginalizing.

The panels on Russia at the recent conferences felt isolated and out of touch, ignoring the war except for the plight of poor middle-class émigré Muscovites and some obscure anti-war poets with their microscopic followings. To be brutally honest: not very interesting in the current context. Is this bad? Yes and no. We certainly need to provincialize Russia and Russian Studies and put them on the periphery while putting in the foreground the subaltern nations of the former Russian empire, the Soviet Union. The current Russian Federation, in fact, is the Third Russian Empire—the Russian version of the Third Reich—and is entering a phase of collapse and disintegration as we speak.

The current Russian Federation, in fact, is the Third Russian Empire—the Russian version of the Third Reich—and is entering a phase of collapse and disintegration as we speak.

But we should be well advised. Decolonization, which is really the only way forward for the field, can be but a passing moment, a simple hype that will inevitably yield a newer hype without leaving the mark that it should. Many scholars who worked within the very traditional paradigm of Russian Studies are now trying to jump on the bandwagon and move on to something trendy at this time.

Worse than that, even now people who made careers collaborating with Putin’s regime and benefitting from its policies, who held positions at KGB-founded “propaganda universities” and openly discredited Ukrainian intellectuals since 2014, are touring the world with lectures on decolonization.

The West’s own promoters of Putin in academia—e.g., Richard Sakwa—did they suffer any negative consequences since Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022? Not unless they were so secret that perhaps even those promoters themselves hardly noticed them.

Ukraine and subaltern nations and decolonization are the hype now—but it will not last. The huge and I am afraid now almost irreversible risk is that the true decolonization that many scholars from subaltern nations have worked for will be drowned in the flood of superficial “decolonizing,” in fact, “re-colonizing” studies.

People who made careers collaborating with Putin’s regime are touring the world with lectures on decolonization.

And before any accountability and justice are served, without any critical reflection over the consequences of this imperial knowledge that is literally killing people today, we will in no time find ourselves discussing how Russia was in fact a very special empire, definitely a more benign one than the British or French, how it was, yes, a subaltern empire or how it fostered a special kind of hybridity that was almost a blessing for those “blind, simple” colonials.

And, yes, surely how we need to be wary of the “bad” type of decolonization “appropriated” by nationalistic and demagogic Ukrainians.And we all know too well what a nationalist label now means for any Ukrainians living in land currently occupied by Russia—a death sentence, no less.

Crime and punishment

This brings us to the most important question of all: the question of responsibility. We have failed as a field of area studies, regardless of how we view the nature of knowledge. We can see it as a representation of reality that must be true. Or we can see it as a constructive process, a journey that creates new knowledge that changes the world.

Whatever your position on this, we have failed. We have failed because our representations of reality were crude, poor, and inadequate. Or we failed to create the new knowledge that could have changed the reality so that this war would not have happened.

I am worried that without any tangible responsibility for the people who knowingly spread false narratives, inadequate theories, caricatures, and ideological rubbish disguised as expertise and knowledge, we will not be able to move forward and make decolonization a lasting reality.

I am not talking about legal responsibility, although suing for defamation and libel may make sense in some cases. But as academics, we are supposed to be autonomous and self-regulating, and we should be able to handle these failures internally by ourselves. Are we capable of it? Are we really?

The question here is how we ensure that those who willingly became agents of influence for the Kremlin are held responsible and accountable for their actions so that this can serve as a warning sign for future generations and the future of our very field.

Once there is a crime, there must be a punishment. This is one lesson of the Russian culture I will be happy to take at its word.

Edited by Mike Cronin

Related:

- Ukraine helped build the Russian empire. Now it stands in the way of its resurrection – Serhii Plokhii

- Unholy trinity, explained: How Kyiv priests created Russia’s imperial “Triune Rus” ideology

- Genocide, assimilation, theft: Kazakh historian reveals Russian colonialism’s ruthless playbook

- The myth of “historically Russian Crimea”: colonialism, deconstructed

- Russian literature is an accomplice in war against Ukraine – literary critic

- “Do Svidaniya” to Russo-centrism: Western schools start decolonizing Eastern Europe studies