This is the fourth year we're inviting you to join the holiday letter-writing campaign to the Ukrainian hostages of the Kremlin of the #LetMyPeopleGo campaign.

In 2015, there were 21 Ukrainians jailed on political motives in Russia.

In 2016 there were 28. In January 2017 - 36. In November 2017 - 56.

This winter, share a bit of love with those who need it most. Joint the winter letter-writing marathon to help the Kremlin's Ukrainian hostages! #LetMyPeolpleGo #SaveOlegSentsov https://t.co/fni5VxeanF pic.twitter.com/C8fTWBPmXu

— Let My People Go_En (@LetMyPplGoUA_en) December 24, 2018

70 are Ukrainian political prisoners of the Kremlin. Most of them have become instruments to the Kremlin's aggressive policy towards Ukraine. Being portrayed as Ukrainian "punishers," "saboteurs," "terrorists," "criminals" on Russian TV, they are the "living proof" that Russia is at danger from attacks of malevolent Ukrainians or Crimean Tatars, stories that Russian state media tells to reinforce the negative image of the country that ousted its pro-Russian President in the Euromaidan revolution. Many of them describe how they were tortured to "confess" of the most wicked plans for Russian media. And these media operations are arguably the most important aspect of the Kremlin's hybrid war against Ukraine. The Crimean Tatars, Crimea's indigenous population, constitute the majority of the prisoners right now. As they are the main resistance force to Russia's occupation of Crimea, the Kremlin is arresting them en masse on fictitious terrorism charges. For an incomplete description of the cases (from November 2017) please read this brochure.

24 are the Ukrainian Navy sailor POWs captured by Russia after an attack in the Azov Sea on 25 November 2018. To date, each one has declared himself a prisoner of war. They are being kept in Moscow. Ihor Kotelianets, the brother of Yevhen Panov, a Ukrainian political prisoner of the Kremlin, writes about letters to the sailors - and political prisoners - thus:

“Right now it’s very important to write letters. It’s more important than sending them parcels. Relatives organize things and food. But there, under the circumstances of an information war, nobody supports them morally. The fight with yourself is the hardest fight. Help them deal with thoughts they don’t need and give them a signal that they are known about, that all their actions are supported, that they are awaited for at home. Now, the Russian FSB instigates the opposite thoughts in them. Help resist this! Write letters! It’s the most important and easiest thing any person can do.”

People all over the world are sending them post cards and letters as part of the holiday marathon of the #LetMyPeopleGo campaign. But there is a problem: the prison guards in Russia only deliver letters and cards written in Russian. Moreover, they have to be of neutral content.

We’re sure that they will be glad for a postcard without words. But considering that some of our readers would like to write something, we invite you to seize the opportunity and “kill two rabbits with one shot,” as we say in Ukraine – write a postcard AND study Russian!

Here are three easy steps to share your love with a political prisoner or POW.

1. Choose a prisoner

It can be either one of the 70 Ukrainian political prisoners of the Kremlin or one of the 24 Ukrainian Navy sailor POWs.

2. Choose your greeting

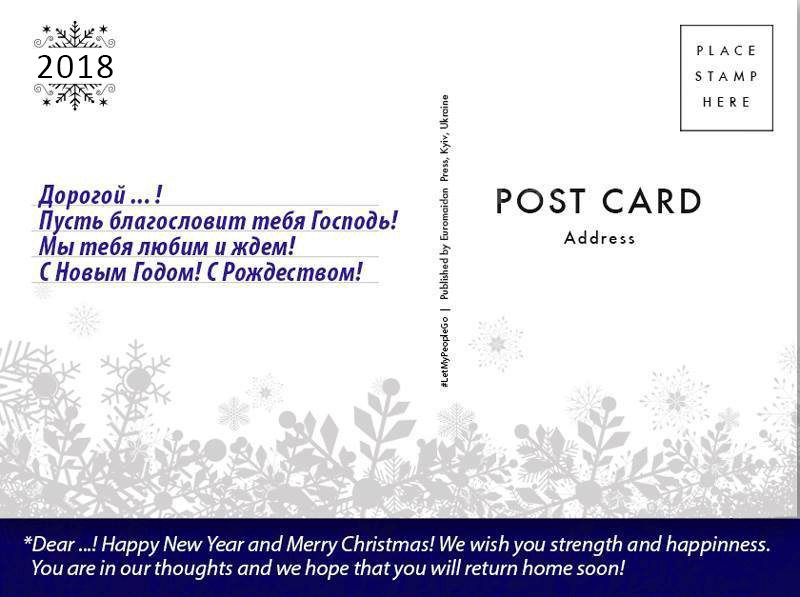

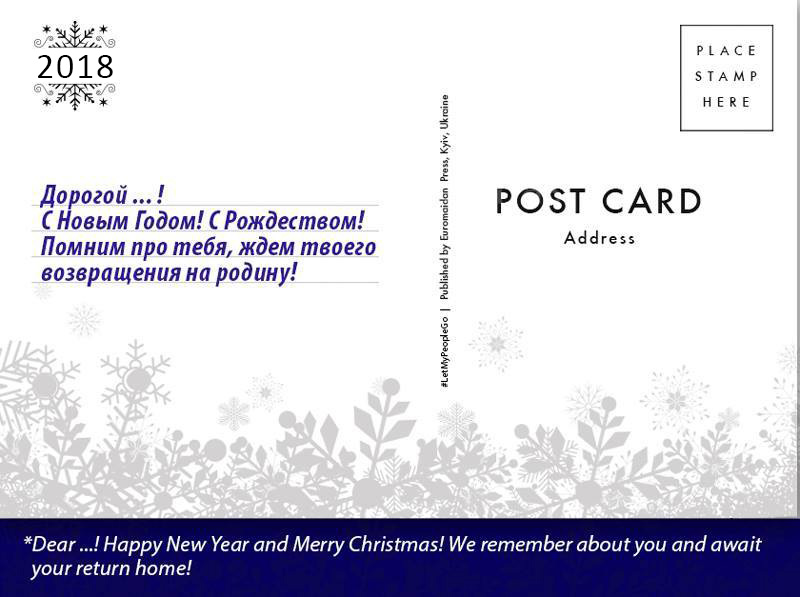

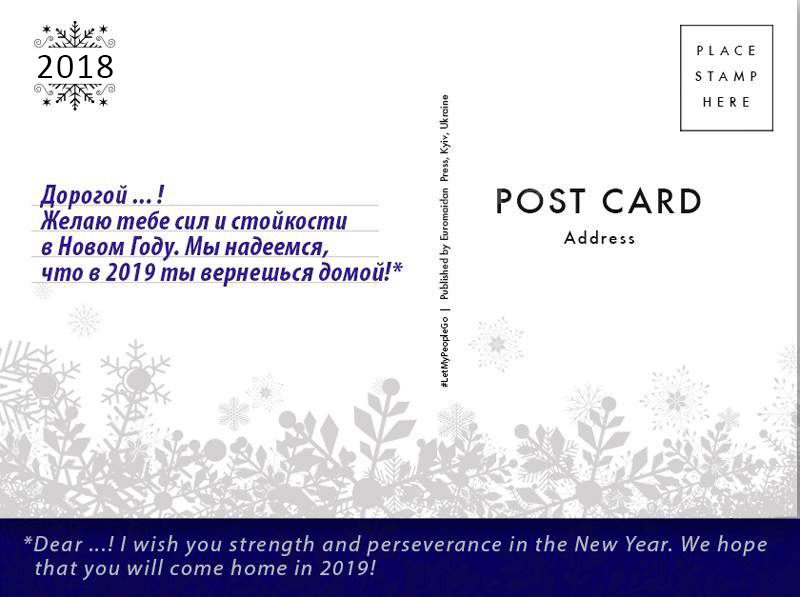

If you are sending a paper letter/postcard (there are options to send letters online for some of the prisoners and POWs), choose your greeting! The prison censors are unlikely to let anything that's not in Russian through to the prisoners. So to be on the safe side, write your message in Russian and keep it apolitical. Below are examples of common greetings.

If you are mailing a letter to a Crimean Tatar political prisoner (cases of Hizb ut-Tahrir, cases of Tablighi Jamaat, Vedzhie Kashka case), keep in mind that the prisoner is a Muslim and might not be celebrating Christmas (therefore, the "С Рождеством!" part can be omitted).

| Russian | Pronounciation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Дорогой (…)! | Daragoi (...)! | Dear (man's name here)! |

| С Новым Годом и Рождеством! | S novym godam ee rojdestvom! | [I greet you] with New Year and Christmas! (И means and; The Russian word for Christmas, Rojdestvo means, literally, "the nativity"). |

| С Новым Годом! С Рождеством! | S novym godam! S rojdestvom! | [I greet you] with New Year! [I greet you] with Christmas! |

| Желаю тебе сил и стойкости в Новом Году! | Jelaiu tebe sil i stoikosti w Novam Gadu! | I wish you strength and perseverance in the New Year! |

| Желаем сил и радости. | Jelaiem sil i radosti. | We wish you strength and happiness. |

| Пусть благословит тебя Господь! | Pust blagaslavit tebia Gaspod! | Let God bless you! |

| Мы тебя любим и ждем! | My tebya liubim i jdiom! | We love you and are waiting for you (Мы, pronounced My, means we) |

| надеемся, что ты скоро вернешься домой! | Nadeiemsia, chto ty skora vernioshsia damoi! | We hope that soon you will return home! (Ты, pronounced ty, means you) |

| Мы надеемся, что в 2019 ты вернешься домой! | My nadeiemsia, chto v 2019 ty vernioshsia damoi! | We hope that in 2019 you will return home! |

| ждем твоего возвращения на родину! | Jdiom tvoievo vozvrascheniia na rodinu! | We await your return home! (the word na rodinu literally means to the motherland, rodit means to give birth). |

| Помним про тебя. | Pomnim pro tebia. | We remember you. |

| Думаем про тебя. | Dumaiem pro tebia. | We are thinking about you. |

If you wish, you can print out the greetings and paste them to the postcard:

| Дорогой Желаю тебе сил и стойкости в Новом Году! Мы надеемся, что в 2016 ты вернешься домой! |

| С Новым Годом! Помним про тебя, ждем твоего возвращения на родину! |

| Дорогой С Новым Годом! Желаем сил и радости. Думаем про тебя, надеемся, что ты скоро вернешься домой! |

| Дорогой Пусть благословит тебя Господь! Мы тебя любим и ждем! С новым Годом! С Рождеством! |

Don't forget to insert the name instead of the (...) after the Дорогой. It comes second, after the last name, in our tables with the addresses for the political prisoners and POWs:

3. Mail it!

- on the envelope, indicate the full name, patronymic, last name, and year of birth of the addressee;

- enclose blank a piece of paper, a Russian postal stamp (if it possible) and an envelope if you expect to receive a reply.

Join the hundreds of people around the world who care about human rights and help resist Russia's aggression against Ukraine.