Kyiv will put its first mini combined heat and power (CHP) plants with built-in protection against Russian shelling into operation by the end of 2025, deputy head of the Kyiv City State Administration Petro Panteleiev said, as the capital enters its fourth winter under large-scale attack on Ukraine’s energy grid.

The new gas-engine units are designed to keep critical heating and power infrastructure alive during blackouts, giving Kyiv a backup source of electricity when giant Soviet-era plants are hit or disconnected from the national grid.

This shift towards smaller, hardened power plants signals how Ukraine’s capital is trying to survive Russia’s long energy war: by breaking up vulnerable mega-facilities into a web of protected nodes that can keep hospitals, water pumps, and district heating running even when the main grid is burning.

What Kyiv is building and why it matters

In his interview with Hromadske, Panteleiev said the city is installing seven gas-piston cogeneration units, six of which are planned to go online by the end of the year.

These mini-CHP plants will:

- Generate over 20 megawatts each—enough to power roughly a third of a city district

- Feed electricity first to large boiler houses so central heating can keep working when the grid fails

- Distribute remaining power to nearby residential buildings and critical infrastructure

- Operate inside purpose-built concrete shelters to withstand near-misses and shrapnel from missile and drone strikes

Panteleiev stressed that these facilities are not just oversized generators: they are full-fledged small power stations designed from the start with fortifications. He noted that each site is being engineered individually, with local grid ties and protection built in from day one, and described the concept as one of the first attempts worldwide to pair distributed CHP with systematic physical shielding against high-intensity missile attacks.

Why giant Soviet-era plants cannot be fully protected

While Kyiv has completed the first level of protection around major energy facilities—gabion walls, earthworks, and other basic structures—the deputy mayor was blunt about the limits of concrete.

Talking about the capital’s two large CHP plants, he said it is “unrealistic to hide a CHP plant in concrete,” pointing out that each facility covers around 100 hectares—the size of an entire residential neighborhood. Even if the city encased some critical elements, nearby components would remain exposed; a successful hit on them could still disable the plant.

The city has poured more than 2.7 billion hryvnias (around $64 million) into second-level protection measures and distributed cogeneration projects, financed from the municipal budget and its own utility company, rather than the state budget. The broader mini-CHP program, including equipment, installation, and shelters, is expected to cost about 10.5 billion hryvnias (around $250 million), with some hardware supplied through international aid programs such as UNDP.

Surviving blackouts: priorities, not miracles

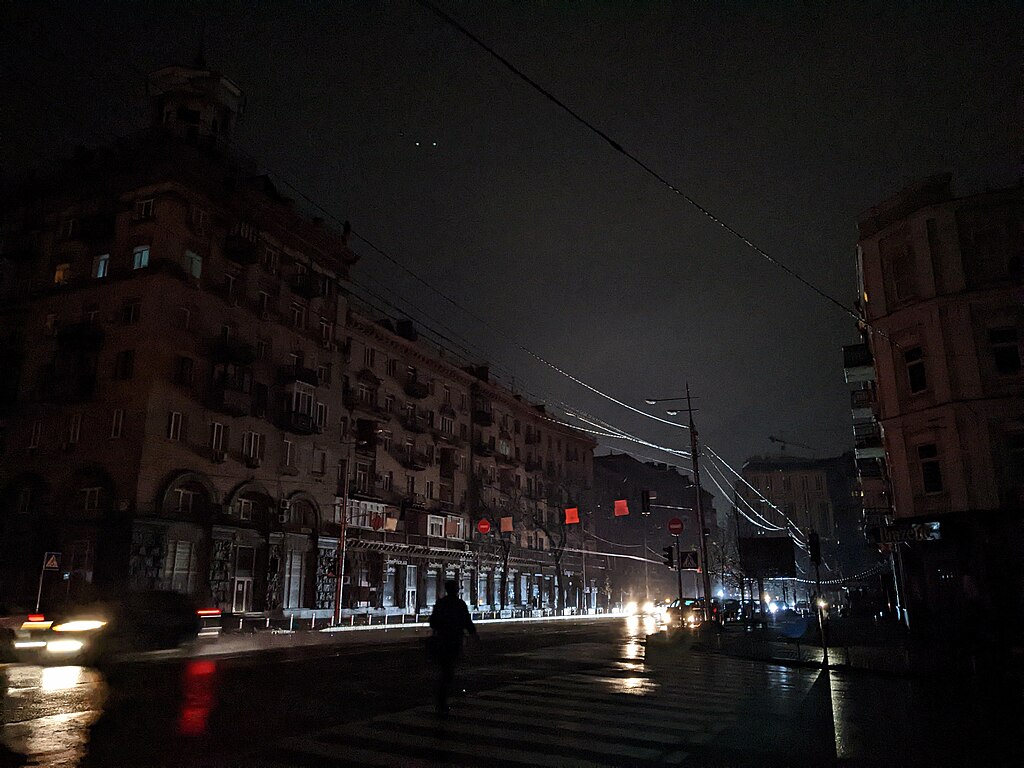

Kyiv’s new mini-CHP network is being built for a specific tactical reality: Russia has destroyed more than half of Ukraine’s pre-war generating capacity and repeatedly forces the country into rolling blackouts with mass drone and missile strikes on power plants and gas infrastructure.

Panteleiev said the city has an emergency “resilience program” for full blackouts, focusing first on:

- Hospitals and maternity wards

- Geriatric and social care centers

- Key water and heating facilities

Kyiv has prepared roughly 300 generators of various capacities and 55 mobile boiler units, a number expected to rise to 70 by year-end, to plug the worst gaps when grid power disappears. But he warned that there is no scenario in which backup systems keep the entire city fully powered: Kyiv normally consumes around 1.3 GW of electricity, and creating a parallel, fully underground energy system would require building something like 15 buried power plants—“from the realm of science fiction in wartime,” he argued.

Instead, the goal is to make sure that even during long outages, citizens can still access heat, water, and basic services while repair crews race to reconnect the main grid. Recent analysis of Ukraine’s energy crisis has shown that where transformers were placed inside robust concrete shelters, most survived repeated Russian strikes—a lesson now being applied to Kyiv’s smaller plants and substations.

A test bed for Ukraine’s wider energy defense

Kyiv’s experiment with mini-CHP plants comes as national authorities roll out a program to fortify 100 critical energy and infrastructure sites across Ukraine by the end of 2025, combining physical barriers, rapid-repair teams, and new operating procedures to keep power flowing under fire.

If Kyiv’s sheltered gas-engine (mini-CHP) plants can reliably keep district heating and water systems running through Russia’s next waves of strikes, they may become a model for other cities seeking to decentralize away from a handful of massive, easily targetable Soviet-era sites.