In a village near Ternopil in western Ukraine, young Olha would crawl under the Christmas table strewn with hay with her siblings, imitating a brooding hen. Her grandmother would throw candies and tangerines—rare treats in Soviet times—while the family interpreted her "clucking" as omens for next year's chicken hatch.

Meanwhile in Mykolaiv, a closed military city in southern Ukraine, Christmas was dangerous. "Church attendance was noted down. If you were caught christening a child or attending Christmas service, it went into your file and you could not be promoted," recalls Svitlana, who grew up there. "Celebrations could only be about the Communist Party or Lenin."

These contrasting experiences reveal how Ukrainian Christmas traditions survived - or perished -- under Soviet rule, setting the stage for their revival after independence and wartime renaissance.

Soviet steamroller

The USSR waged war on Christmas, allowing holidays only if they served state ideology. Christmas, connecting Ukrainians to both Christianity and national identity, was particularly threatening – a fact exemplified by mass arrests of Ukrainian dissidents during Christmas celebrations.

The state redirected celebration energy toward New Year and appropriated Christian symbols, crafting a secular holiday with Father Frost replacing St Nicholas and one day of champagne-soaked abundance amid everyday socialist deprivation.

The splurge was delightful for many children: Olivier salad -- cubes of mayonnaise-soaked root vegetables and bologna, if it was found in the empty stores during the Perestroika -- jellied meat and, occasionally, red caviar saved up for months were rare treats. If your mom was lucky, after queuing all evening, the kids would have a kilogram of tangerines. If she knew someone at the store, your New Year's table might feature a finagled stick of one of the two types of coveted mass-produced salami.

It was also one of the few times in the year that kids would get sweets – not the three usual types of caramels, but real chocolate. “You stood there holding the package, dumbfounded with happiness,” Svitlana Chebanova from Mykolaiv recalls. Now grown up, she says the scent of chocolates in New Year’s candy packs still serves as a portal back to her childhood. “I inhale it sparingly, careful not to let it escape.”

Yet beneath the feast amid deficit, many sensed that this socialist holiday's forced abundance masked spiritual poverty.

"New Year had no meaning except to eat well, watch the President's address, watch concerts, go to sleep," recalls Olha. "But Christmas was magic."

Authentic Ukrainian Christmas magic

This magic proved resilient. In western Ukraine, where Soviet control came later and was weaker, traditions survived more intact.

Olha Zhuk's grandparents in the village maintained a full ceremonial Christmas Eve supper with twelve dishes. In Ukrainian folk belief, Christmas Eve (Sviatvechir) was when the barriers between worlds thinned, allowing ancestor spirits to visit their families. The twelve traditional dishes, all meatless, had to be shared with deceased relatives who were invited to the table -- families would leave portions on the windowsill or at empty place settings.

The church was closed, but women would find the keys and sing religious hymns inside. The solemn dinner would start and end with a prayer.

"It wasn't just about food," Olga explains. "Everything was connected to life and death, protecting life so no misfortune would come to your family, so no one would die, so no one would fall ill, so fire wouldn't burn your household, so everything would grow well, so hens would lay eggs, calves would be born, so you'd have good fortune and get married - but also not forgetting your ancestors."

This cosmic drama played out through intricate customs. The grandfather would bring in a didukh—a sheaf of wheat saved from the summer harvest—symbolizing the family's ancestors. Children would scatter hay under the tablecloth, recreating the manger where Christ was born. Garlic warded off evil spirits on the four corners of the table. The grandmother would check if the Christmas candle burned straight—a crooked flame meant death in the family.

Yet even in Russified cities, Ukrainian Christmas traditions persisted in subtle ways. Olena Nazarenko, who grew up in Kyiv in the 1970s, recalls her family always preparing kutia (a wheatberry porridge with poppy seeds and honey dating back to prehistoric times), and uzvar (dried fruit kompot) for Christmas Eve supper, though they couldn't openly celebrate the religious holiday:

"My father would explain these were Ukrainian traditions, passed down from our ancestors. We might not understand why we do them, but we do them because our grandmothers did."

In these times, people whispered about western Ukraine, where Christmas was truly alive - not just through food, but through meanings that couldn't be captured by simply recreating the festive meals.

Meanwhile, in southeastern industrial cities, preservation required courage. One music teacher in Mykolaiv dared to teach students ancient Ukrainian carols. "The words about God's Son being born sparked something in me, though I wasn't raised religious at all," Svitlana, who had never heard about Christmas in her family, recalls. "There was suddenly meaning where there had been none."

Renaissance of Christmas traditions after Ukraine's independence

When Ukraine gained independence in 1991, Christmas traditions began a gradual resurrection. For many families, especially in eastern Ukraine, it was a journey of rediscovery.

"Christmas appeared in the 90s, first as something semi-underground. Something new, interesting in its incomprehensibility and the fact that it was now 'allowed,'" recalls Oleksandr Kotenko, who grew up in Mykolaiv. "The understanding of Christmas's meaning came with joining church. New Year began retreating to the background, but very gradually."

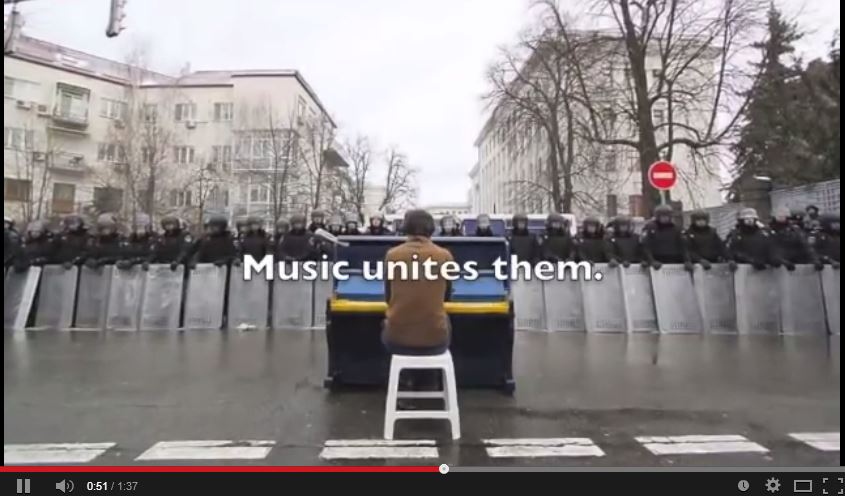

The changes accelerated with Ukraine's pro-democracy movements. "Significant changes came with 2004, 2014," Kotenko notes. "New Year became increasingly associated with Soviet times. Meanwhile, the Christian meaning of Christmas was joined by national traditions. We started learning carols. Sometimes we sang them on the street. We removed the Soviet-style star from the Christmas tree. Santa Claus was replaced by St. Nicholas."

Youth organizations played a crucial role in this revival. Lesia Tylina spread Christmas traditions by leading scout activities. "I stopped celebrating New Year entirely - it was a form of protest because it was associated with Soviet times and had absolutely no meaning," she says. "We would go to scout camps for New Year, while for Christmas we began collecting carols, reviving them."

For Lesia's scout group, caroling wasn't just about tradition - it was about service. "Our best Christmas spirit was when we went caroling not just for money but visited adult care homes - places where nobody goes. When we came there, brought presents, sang carols... that's when I felt the true Christmas spirit."

People of the earth

Meanwhile, the sparks that the courageous music teacher planted in Svitlana’s heart led her to lead carolers throughout the streets and shops of Mykolaiv, a city that until recently knew no Christmas.

However, for her, the pagan roots of Ukrainian Christmas are no less valuable than the Christian layer:

“It is natural for our culture; it is oriented at the birth of the new sun. All these songs underscore our earthliness, that we are people of the earth, of all these forces of nature, and that we have all these traditions rooted in very ancient times which survived by some miracle, despite religious, imperial bans. It’s a miracle of miracles that our carols, rituals, and culture of Christmas survived,” Svitlana shares.

Despite growing up in the Russified, deeply Soviet environment of Mykolaiv, her teacher's ancient songs awakened something profound in her soul.

It’s a miracle of miracles that our carols, rituals, and culture of Christmas survived

“They weren’t only about the texts and music. There is something inexplicable, unexpressible that thrills, uplifts you inside, delights your soul. I wouldn’t even call it the Spirit of Christmas, because Christmas is about hope and that the good will win. It’s about you being alive, that the sun will rise anyway, that spring will replace winter.”

Ironically, the very pagan songs that stubbornly persisted despite church attempts at their eradication played a great service for religion. Their ancient vibes were powerful enough to withstand Soviet social engineering and became a living vessel for Christian concepts in a society that worshipped Marx, Engels, and Lenin.

This impressive vitality has been traced to the pre-Christian holiday of Koliada, a celebration of the birth of the world. Beneath the words, melodies, and religiously observed food rituals are millennia of uninterrupted culture – a rock-solid base giving Ukrainians meaning and support as Russia attempts to destroy their physical existence.

Wartime renaissance

Russia's war against Ukraine intensified this return to traditions. What was once village lore studied by ethnographers is becoming a lived experience for modern Ukrainians seeking to strengthen their identity.

Olha Hodovanets, whose husband serves in the artillery, now sends traditional Christmas baked goods to the front. "I bake medivnyk (honey cake) according to Daria Tsvek's recipe - it's our family's Christmas tradition. I make Polish piernik, cheese stollen, plain stollen, nut and orange rolls, poppy rolls... everything from the best ingredients," she says.

Her treats travel in large boxes through Nova Poshta, connecting the home front to the battlefront through taste and tradition.

Her children sing carols to the neighbors while carrying colorful stars, ensuring the tradition lives on. Large processions of star-bearing carolers, once common only for west Ukraine’s Lviv, have now spread to other cities. Kyiv saw one of the largest ones yet this year, with an especially poignant scene as carolers passed an alley of flags commemorating soldiers who died defending Ukraine from the full-scale Russian invasion of 2022.

The war has also accelerated Ukraine's break with the Russian world. This Christmas, most Ukrainians will celebrate on 25 December rather than 7 January, aligning with the Western calendar and further distancing from Moscow's influence.

Passing the torch

Yet preserving authentic traditions poses challenges. "I can pass on maybe 20% of what my grandmother knew," Olha Zhuk admits. "My child won't experience this atmosphere where everyone knows all the carols by heart and can sing for 2-3 hours."

The magic of Christmas was deeply tied to village life - customs about ensuring good harvests make little sense in urban apartments. The ceremony required a large family:

"Christmas is about having many people at the table," Olha explains. "When my friend who stayed in the village celebrates, they need multiple tables through two rooms to fit everyone. They cook two pots of borsch, two pots of holubtsi. That's where the magic lies."

Modern families are finding their own way. "We don't force our children into ritualism," says Oleksandr. "But we want to pass on the spirit of Love through something pleasant. We teach them about the roots of these celebrations, about Christianity itself."

But the meaning of Christmas exceeds faith; it is about identity, writes scholar Olesia Isaiuk.

“Specific forms of celebration - kutia, carols, nativity scenes - are about what makes us Ukrainian. This is important because it provides answers to basic meaning-making questions: Who am I? Whose am I? Why am I? What is this all about? And so on.”

This makes the holiday and its elaborate traditions increasingly important in Ukraine now, despite modern distractions and the exhaustion of everyday life—Ukrainians have no official holidays due to martial law.

Soviet memories run strong in many places, though. Kindergarten parties still gravitate towards Soviet-style Father Frost and splurging on candy that is no longer a deficit good. For many industrialized cities in eastern Ukraine, Christmas is still a foreign concept compared to New Year's.

Nevertheless, what once underground resistance to Soviet rule is becoming increasingly popular. Now, commercial kits for traditional Christmas decorations and food kits target social media feeds. Multiple albums of reimagined Ukrainian carols compete for spots on holiday playlists. What was once the domain of "nationalist freaks" has entered the mainstream of Ukrainian life - not through force, but through the magnetic appeal of authentic tradition.

And while some traditions fade, their core meaning endures. Christmas remains what it was for generations of Ukrainians—a celebration of life's triumph over darkness, of hope's victory over despair. As Russia wages war to destroy Ukrainian identity, families across the country gather for Christmas Eve supper, leaving portions for absent loved ones—some separated by death, some by war. The candle burns, prayers are said, and carols are sung.

Life continues, as it has for generations, carrying meaning that even the Soviet steamroller couldn't crush.

Related:

- Carols against the USSR: the tragic 1972 Vertep and KGB’s mass arrests of Ukrainian dissidents (photos)

- How the Soviets stole Ukrainian Christmas

- A Ukrainian Christmas music playlist from Euromaidan Press