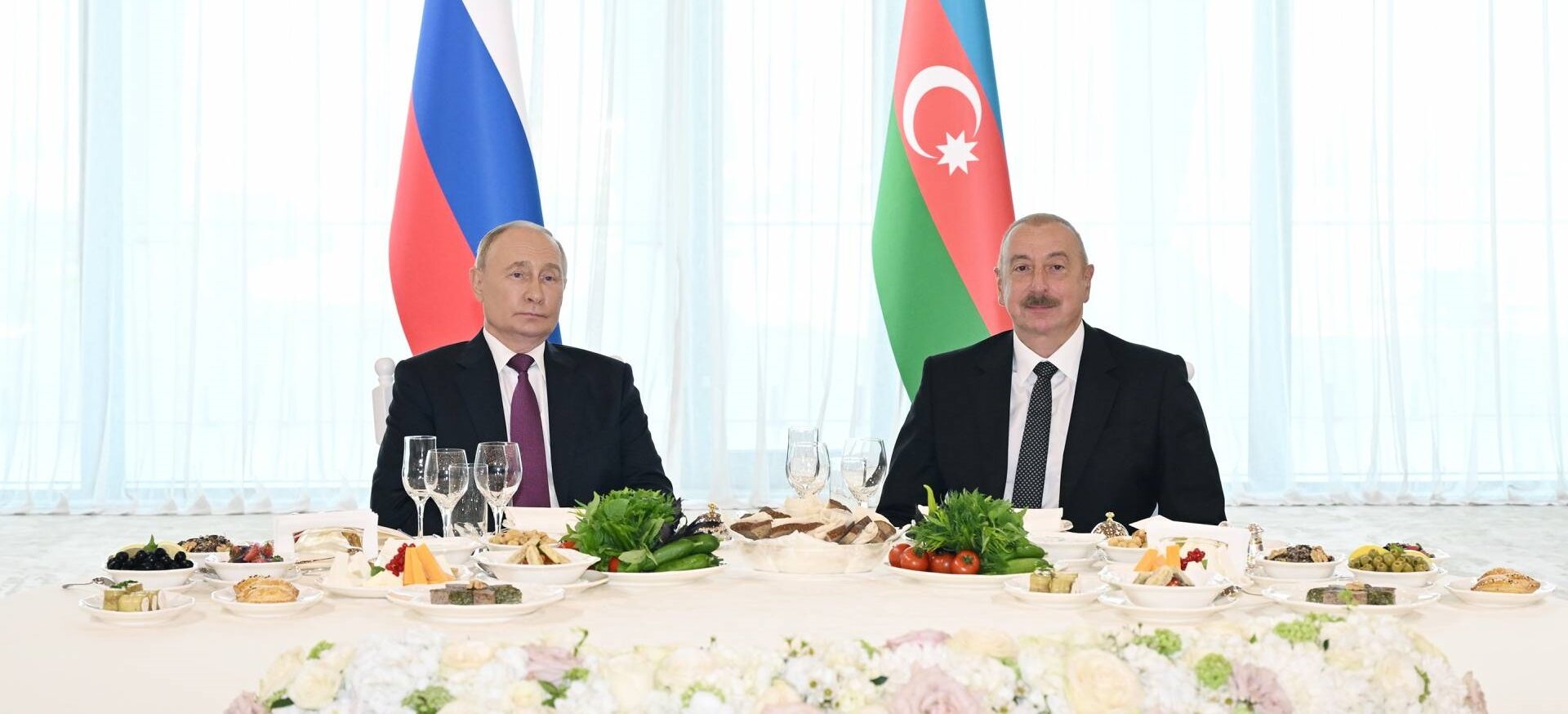

As battles continue to unfold in Russia’s Kursk Oblast, where the Ukrainian army is waging an offensive, one might expect Vladimir Putin to remain in Moscow. Instead, the Russian leader has made a visit to Azerbaijan. Why now?

Putin, whose international travel has been severely limited due to sanctions and an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court, likely aims to demonstrate to the world that he still maintains some diplomatic support. However, the visit’s implications run deeper, with energy politics at its core.

The gas issue is presumably central to the negotiations. Following the invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions, Russia has drastically reduced its gas exports to Europe, impacting its revenues. In contrast, Azerbaijan has signed an agreement with the EU to increase its exports, positioning itself as an alternative supplier.

Another crucial aspect is the transit of Russian gas through Ukraine. The current contract expires at the end of 2024, and Kyiv, refusing renewal, explores alternatives – notably, substituting Russian gas with Azerbaijani supplies for EU transit. Volodymyr Zelenskyy confirmed this as “one of the proposals” under consideration.

On the surface, this idea seems advantageous:

- Depriving Moscow of substantial revenue (over $10 billion during the two years of the full-scale war)

- Ensuring continued EU gas supply

- Maintaining Ukraine’s transit income.

Yet, Ukrainian energy expert Mykhailo Gonchar cautions this might mask another Kremlin stratagem. Euromaidan Press delves deeper, investigating potential hidden agendas in this high-stakes energy chess game.

“Putin’s scheme under Aliyev’s flag”

Putin and Azerbaijan’s President Aliyev are discussing a scheme to continue Russian gas flow through Ukraine under the guise of “Azerbaijani” gas, Mykhailo Gonchar believes.

“Azerbaijan doesn’t have that much free gas. Aliyev claims there’s plenty in the ground and that they will extract it. This is true, but it’s not available now. Gazprom, on the other hand, has plenty of gas because they’ve lost the European market,” Gonchar told Euromaidan Press.

Gazprom, facing financial difficulties, is seeking ways to improve its situation.

Having lost access to the EU market through a combination of sanctions and failed attempts at weaponizing energy, Russia aimed to pivot its exports to China. However, Moscow was in for a rude awakening: due to its diversified energy sources, China found itself in a strong bargaining position and started demanding domestic, subsidized gas prices. This led to the indefinite stalling of the Power of Siberia-2 pipeline which was initially targeted to start in 2024, yet is now rendered unprofitable by Beijing’s demands.

This indicates that Russia will attempt to make a comeback to the EU market, Gonchar believes.

Maintaining transit to Hungary, Slovakia, and Austria – countries still receiving Russian gas via Ukraine – would be a strategic win.

“Previously, this transit was considered a minor gas flow that could be neglected. However, now Putin is desperately looking for ways to return to the European gas market,” the expert explains.

The scheme is straightforward: An Azerbaijani company would contract with these European countries. Unable to meet demand alone, Azerbaijan would purchase additional gas from Russia, effectively relabeling Russian gas as Azerbaijani for European consumption.

“I would call this Putin’s scheme under Aliyev’s flag,” Gonchar summarizes.

Dissecting the Russia-Azerbaijan gas plan

In a column for Ukrainian publication Dzerkalo Tyzhnya, Gonchar elaborates on the scheme, explaining that Moscow aims to frame this gas plan as both European and peacemaking.

The “peacemaking” aspect lies in the negotiations about Russian gas transit through Ukraine, while the “European” element involves pro-Russian Hungary and Slovakia. Crucially, the gas source must appear non-Russian.

Gonchar outlines how the pieces fit together:

- June saw “sudden” media reports about Azerbaijan’s readiness to increase gas supplies to the EU.

- Putin and Aliyev likely discussed the Azerbaijani cover for Russian gas during their Kremlin meeting on 22 April.

- On 7 May in Baku, Slovak PM Robert Fico and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev signed a strategic partnership declaration and shared ambitious gas plans, with Aliyev proposing to increase supplies from 8 to 12 billion cubic meters by 2024, and to 20 billion by 2027.

“The irony is that Azerbaijan lacks free gas resources, while Slovakia doesn’t need that much gas, consuming only about 4.5 billion cubic meters annually. The true agenda is clear, though unspoken,” Gonchar notes.

Both Hungary and Slovakia have emphasized their dependence on Russian gas and oil. Viktor Orban’s appearance at the Organization of Turkic States forum in Shusha, Azerbaijan on 6 July likely served this agenda.

This “Azerbaijani” gas scheme would not only sustain Gazprom but also funnel additional revenue to Russia’s war budget. For every dollar paid to Ukraine for transit, Gazprom could receive $10-15 in revenue, depending on EU market prices.

In reality, no Azerbaijani gas would transit through Russia. Instead, a paper trail would create the illusion of transit, with payments going to a provider company, possibly registered in Switzerland or anywhere else in Europe.

“This payment for non-existent services will essentially become a slush fund for involved parties,” the expert concludes.

What is next?

As the scheme unfolds, Russia is expected to employ various tactics to persuade Ukraine to accept it. Their propaganda efforts will target both European and Ukrainian audiences with different messages.

In Europe, they’ll emphasize the need for negotiations. In Ukraine, they’ll push two main narratives:

- Continuing gas transit allegedly protects gas transportation infrastructure from Russian attacks.

Gonchar counters this claim: “Russia has repeatedly struck underground gas storage facilities in the Lviv region, even with the transit agreement in place and Gazprom profiting from gas sales to Europe.”

- Stopping transit would leave several Ukrainian regions without gas.

Gonchar refutes this too, citing historical evidence: “In 2009, when Gazprom halted supplies to Ukraine and Europe, we reversed the gas transportation system. For two weeks during peak winter, Ukraine relied on domestic production and underground storage. No region experienced gas shortages.”

****

As the 2024 deadline for the Russian gas transit contract looms, Ukraine faces a critical decision. The complex interplay of gas diplomacy between Russia, Azerbaijan, and Europe underscores the persistent challenge of reducing dependence on Russian energy. Despite the absence of a direct Azerbaijan-Ukraine pipeline, a potential substitution scheme could allow Russian gas to be rebranded as Azerbaijani and exported to Europe.

As Ukraine considers its options, the international community must remain vigilant about the long-term implications of apparent short-term benefits, ensuring that efforts to diversify energy sources don’t inadvertently reinforce Russian influence.

Read more:

- Why Russia clings to gas lifeline amid Ukraine’s Kursk incursion

- Kursk incursion: why is Ukraine taking the war to Russian soil?

- Kursk incursion: experts debate Ukraine’s objectives as Kyiv consolidates blitz gains

- Ukraine’s surprise Kursk incursion: lifting spirits or stretching resources?