The Kremlin has long justified its territorial ambitions by invoking the need to reclaim “historical lands.” This rhetoric reached a fever pitch before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, when Russian President Vladimir Putin penned a lengthy treatise on Ukrainian history—as he perceived it. In this document, Putin asserted that parts of Ukraine rightfully belonged to Russia and went so far as to deny the very existence of a distinct Ukrainian nation. He reiterated these arguments in a history-laden speech on 23 February 2022, attempting to legitimize the impending invasion.

However, the events unfolding in Kursk Oblast, a region in western Russia, starkly illustrate the flaws in this narrative. When Ukrainian troops advanced into the area on 6 August 2024, they were greeted by many locals speaking Ukrainian—a poignant reminder of the region’s Ukrainian heritage. This ironic turn of events underscores the fallacy of Russia’s oversimplified claims about historical ownership.

Indeed, contrary to Putin’s assertions, a Russian population never dominated any of the contemporary Ukrainian regions. Moreover, Putin’s historical argument has backfired spectacularly.

At the same time, historical claims alone cannot dictate geopolitics. Forceful border changes could lead to endless conflict and Ukrainian officials have made it clear that Ukraine does not seek to alter internationally recognized borders or claim Russian territory.

Nevertheless, Ukrainian military operations will continue on Russian soil to disrupt Russia’s capacity to wage war until Russia is ready to negotiate a “just peace,” which must include the restoration of Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders as they were before 2014.

Parts of Russia’s southwest were predominantly Ukrainian until the 1932-1933 genocide

In August 2024, Ukrainian forces occupied Sudzha, a town where Ukrainians constituted 61% of the population in 1897, according to the Russian Empire’s census. This demographic makeup was not unique to Sudzha; many districts in contemporary Russia had a Ukrainian majority a century ago.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, portions of present-day Russia—specifically, southwestern Kursk and Belgorod oblasts, and southern Voronezh Oblast—belonged to Ukraine’s Sumy, Okhtyrka, Kharkiv, and Ostrohozk regiments (polks). These polks, administrative units within Ukraine’s Cossack State, were led by elected commanders called polkovnyks, who wielded both military and civilian authority.

In the late 17th century, eastern Ukrainian polks enjoyed considerable autonomy within the Russian Empire, which balanced between controlling Ukrainian people and utilizing their strength as an effective military force on the southern border. However, this autonomy eroded after Ukrainians allied with Sweden in the Great Northern War and were defeated. By 1768, Ukrainian lands had fallen under full Tsarist control, losing their autonomy.

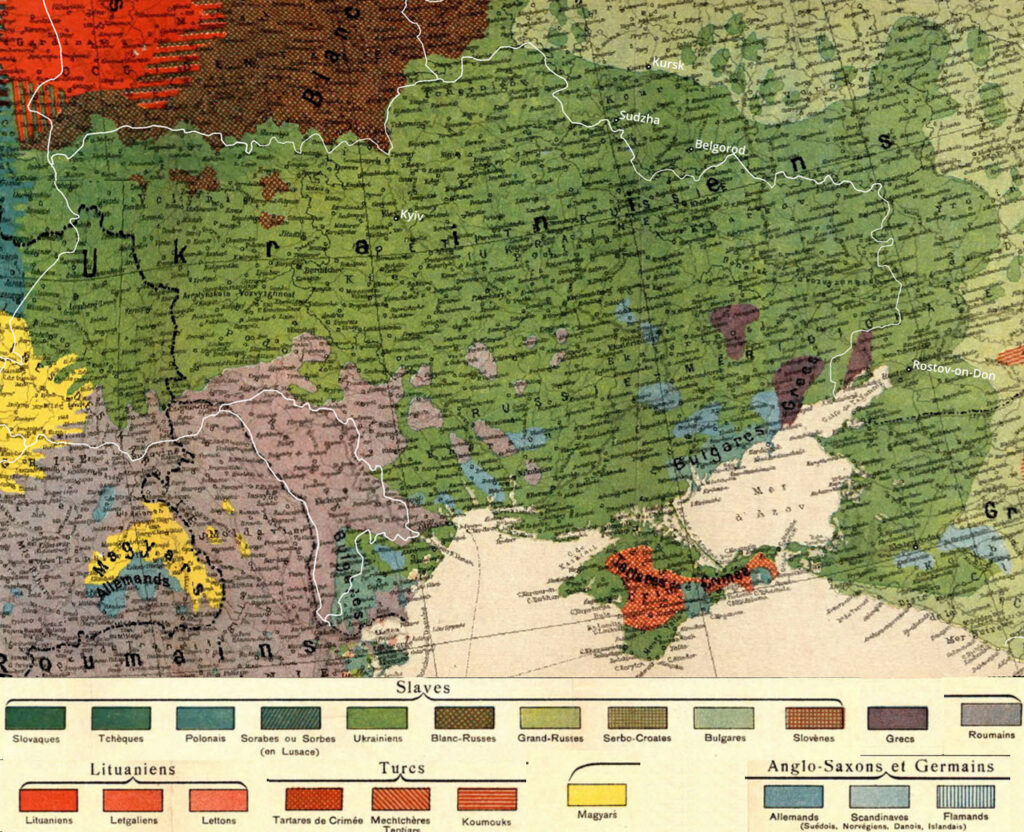

Despite this, throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these parts of contemporary Russia maintained a significant Ukrainian presence.The 1897 Russian census, along with 61% in the town of Sudzha, Ukrainians were widely present in other towns: 51% in Ostrohozk, 43% in Hrayvoron, 82% in Biryuch, and similar numbers in the surrounding rural areas. Historical maps, including those from the early 20th century, depict these areas as part of a Ukrainian ethnic territory defined by the language spoken.

The maps include the 1915 “Overview Map of Ukrainian Lands” by Ukrainian Georgrapher Stepan Rudnytskyi, the 1912 “Ethnographic Map of Slavic Lands” by Czech archeologist, anthropologist and ethnographer Lubor Niederle, the 1918 Swiss Ethnographic Map of Europe, and many more.

The opposite situation — where some territories within present-day Ukraine were historically more populated by Russians than Ukrainians — did not occur.

The only areas that were not predominantly Ukrainian were central Crimea, southern Odesa Oblast, Zakarpattia Oblast, and south Chernivtsi Oblast. where Ukrainians were the second-largest ethnic group. However, Russians were not the dominant group in these Ukrainian regions. Depending on the district, Bulgarians, Romanians, Crimean Tatars, Hungarians, Romanians, or German colonists formed the largest ethnic groups.

Early 20th-century Ukrainian geographers and sociologists—Stepan Rudnytsky, Mykyta Shapoval, and Volodymyr Kubiyovych—estimated the Ukrainian ethnic territory between 728,500 km² and 905,000 km², based on censuses and ethnographical data. The lower estimate included only territories with a strong Ukrainian majority.

For context, Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders encompass 603,700 km², suggesting that Ukraine, rather than Russia, could potentially claim the return of “historical lands.”

The extent of the ethnic cleansing of Ukrainians

A dramatic demographic shift occurred in 1932-1933. Previous Russian and Soviet attempts to assimilate Ukrainian identity into Russian had yielded only limited results. However, Stalin’s genocide by starvation, known as the Holodomor, struck southeastern Ukraine with particular ferocity, including Ukrainian lands now part of Russia.

Soviet authorities and collective farms forcibly confiscated all food and livestock, selling it abroad while imposing border restrictions. This engineered famine resulted in an estimated 4 million deaths during 1932-1933.

The 1926 USSR census recorded 23 million Ukrainians in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, with an additional 7.8 million in the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic. For context, only 2.3 million Russians lived in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic at that time, indicating that official borders between Ukraine and Russia favored Russian territorial claims over Ukrainian ones.

In the aftermath of the 1932-1933 genocide, the 1939 census revealed a stark decline in the Ukrainian population. The total number of Ukrainians in the Soviet Union had decreased from 31.2 million to 28.1 million. Conversely, the Russian population surged from 77.8 million to 99.9 million during the same period. Ukrainians and Kazakhs were the only nationalities to suffer such a precipitous population decline, while other nationalities in the USSR grew more or less in proportion to the overall population increase from 147 million to 170.6 million.

Comparing maps of the highest Holodomor casualties with pre-Holodomor ethnic distributions explains the subsequent rapid increase in Russian numbers and decrease in Ukrainian population in these “cleansed” lands. The USSR’s ensuing policy of Russification further suppressed the remaining Ukrainian populace.

The lost identity of Ukrainians in Russia revealed by Ukraine’s Kursk offensive

Unlike those in Ukraine, who experienced a revival of Ukrainian culture and identity after 1991, the remaining Ukrainians in Russia lacked this opportunity. They gradually lost their identity and national memory over generations. According to Russian censuses conducted after 2000, the proportion of people identifying as Ukrainians in formerly Ukrainian-populated areas dwindled to a mere few percent.

Many who began identifying as “Russian” in censuses still retained a vestige of local identity, though often without recognizing or acknowledging its Ukrainian roots. This identity was frequently maintained in a provincial manner. A striking example of the consequences of Soviet genocide and Russification policy was displayed on a contemporary Russian TV show, featuring a young woman from Kozynka village in the Hrayvoron district of Belgorod Oblast.

The woman shared local recipes with the TV hosts and, at one point, began speaking “in our local dialect” to demonstrate it. The hosts struggled to understand, commenting that the words of this “unique dialect can’t be found in any dictionary in the world.”

Neither the hosts nor the young woman seemed to realize she was speaking the same language millions of Ukrainians use just across the border. Moreover, the local customs she described resembled Ukrainian rather than Russian ethnic culture, yet this connection went unrecognized by both the hosts and their guest.

This remarkable instance not only reveals that remnants of Ukrainian culture persist in these Russian areas but also underscores the extent of historical amnesia and cultural destruction local Ukrainians have endured under Soviet and Russian state control.

It’s difficult to predict whether these people would ever identify as Ukrainian again, especially younger generations, even if Russia were to become democratic and allow self-determination. The Ukrainian population in these areas suffered significant losses, and Russian propaganda has long worked to assimilate the remainder.

Nevertheless, when Ukrainian troops entered Sudzha and surrounding villages in Russia’s Kursk Oblast, many elderly locals spoke Ukrainian to the soldiers. Overall, there was no civil resistance to the Ukrainian army, and numerous videos published by soldiers showed positive or at least neutral attitudes toward the Ukrainian forces.

As an example, an elderly woman, speaking Ukrainian, told a Ukrainian soldier that authorities had abandoned her village near Sudzha, while her son used to come from Sudzha to bring her food:

Another video depicts two elderly women speaking fluent Ukrainian while politely requesting a ride from Ukrainian soldiers. When a soldier expressed surprise at their language choice, one woman replied that although she speaks Ukrainian, she does not identify as Ukrainian.

Yet another video shows a Ukrainian soldier gifting his blue-and-yellow bracelet to a Russian girl, who again understands Ukrainian and replies to the soldier, though the video is too short to note how well she speaks.

Yevhen, a soldier who fought in the Kursk offensive operation, also told Euromaidan Press that some locals he encountered spoke Ukrainian fluently:

“Surprisingly, some even speak Ukrainian fluently – better than some people in Kyiv.”

In these remote areas, time seems to have stood still, he noted. Local residents still reference the Commusit Party, Central Committee, and Lenin—vestiges of the Soviet era that persist. Some inhabitants demonstrate uncertainty about their current government.

The warm reception many locals in Kursk oblast gave Ukrainian soldiers stood in stark contrast to the numerous protests Ukrainians staged in Russian-occupied territories at the war’s outset.

Temporary occupation normal in wartime, but international law rejects provisional border changes

Russia’s justification for its actions in Ukraine based on historical claims is not only flawed, but destabilizing. If every nation pursued territorial changes rooted in historical narratives, it could spark widespread conflicts. The post-World War II international order, emphasizing respect for existing borders and territorial integrity, was designed precisely to prevent such disputes.

However, temporary occupation of another country’s territory during wartime for military objectives falls within international law and the rules of war, provided occupying forces do not violate human rights, according to lawyers and defense experts. This nuanced perspective highlights the complexity of the situation.

On 14 August 2024, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy held a meeting focused on the situation in Kursk oblast, where he announced the establishment of a military administration in the occupied areas. Zelenskyy emphasized Ukraine’s commitment to defending its territory and citizens while strictly adhering to international humanitarian law.

The discussion included the creation of a “buffer zone” for self-defense and ensuring compliance with international conventions. The president also ordered his staff to ensure humanitarian aid, such as food and medicine, reaches civilians in the occupied territories of Kursk oblast.

Kateryna Rashevska, a lawyer at the Regional Center for Human Rights, stated that under the Hague Convention, the establishment of military administrations in the part of Kursk oblast occupied by Ukraine will confirm effective control over this territory and is entirely justified.

“Full regulations governing the status of occupied territories will begin to operate, particularly regarding the guarantees and rights of the civilian population. This is an absolutely adequate, logical, and rational decision under the circumstances,” Rashevska explained.

Oleksandr Khara, a defense expert at the Ukrainian Center for Defense Strategies, emphasized that Ukrainian authorities have never laid claim to Russian lands, nor do they do so now.

“Throughout Ukraine’s entire history, no serious politician has ever made any claims against the Russian Federation based on historical territories. Although you know well that Kursk oblast has long been populated by Ukrainians. And if we were like Putin, we could claim Kursk and many other oblasts, but we don’t do that,” Khara explains.

He adds that Russian military personnel and their mercenaries, regardless of location, are legitimate targets for Ukraine. Therefore, the temporary occupation of Russian land is a justified tool. Moreover, the Kursk operation finally restored a certain normalcy regarding war perception.

“It was absolutely abnormal that we were not allowed to operate on enemy territory. Now we are restoring that normalcy,” Khara asserts. This perspective underscores the strategic shift in Ukraine’s military approach.

Serhiy Zayets, a lawyer specializing in human rights, notes that by establishing control over certain territories, Ukraine effectively takes responsibility for the civilian population in these areas. Consequently, if Ukraine controls these territories, the issues of food, water supply, and the daily needs of the population in the occupied territory also fall under Ukraine’s purview.

Ukraine pursues military objectives on enemy territory, denies annexation goals

Unlike Russia, Ukraine has no intention of expanding its internationally recognized borders by annexing occupied Russian lands. This stark contrast in objectives underscores the defensive nature of Ukraine’s military strategy.

Heorhiy Tykhyi, spokesman for Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, emphasized that the Ukrainian offensive in Russia’s Kursk oblast aims to disable Russia’s ability to launch strikes on Ukrainian territory, without any political claim to Russian land.

Tykhyi stressed that the operation was partly necessitated by Western partners’ prohibition on long-range strikes against Russian military bases. This restriction left Ukraine with no other means to protect border areas than to expand control on Russian soil.

“Unlike Russia, Ukraine doesn’t need someone else’s [territories],” he stated. “Ukraine is not interested in taking territory in Kursk Oblast, we want to protect the lives of our people.”

He noted that since the beginning of summer, more than 2,000 strikes were launched against Ukraine’s Sumy Oblast from Kursk Oblast alone, including 255 guided air bombs and over 100 missiles.

“Unfortunately, Ukraine does not have enough opportunities to deliver long-range strikes with the available weapons to protect itself from this terror. Our partners have not made such decisions. Therefore, there is a need with the help of the Armed Forces to clear these border areas of the Russian military contingents that are attacking Ukraine,” Tykhyi explained.

He added that Russian raids on Ukrainian territory would cease once Russia agrees to restore a just peace, including the reinstatement of Ukraine’s pre-2014 internationally recognized borders.

Mykhailo Podoliak, advisor to the head of the presidential office, echoed this sentiment in a Telegram post on 16 August 2024:

“Ukraine has no interest in occupying Russian territories. Ukraine is solely engaged in a defensive war, strictly within the bounds of international law… However, if we are to discuss potential negotiations—and I emphasize, potential negotiations—we will need to bring Russia to the table on our terms.”

Podoliak argued that compelling Russia to negotiate requires not only economic and diplomatic tools but also military means to inflict significant tactical defeats on the Russian army. He also emphasized the importance of influencing public opinion within Russia.

“The negative changes in the psychological state of the Russian population will be yet another argument in favor of starting negotiations,” Podoliak concluded.

Related:

- Russia resorts to nuclear blackmail amid Ukraine’s Kursk incursion

- Last ride home: The man who brings back Ukraine’s fallen heroes

- The EU should help Ukrainian refugees return home

- Kursk offensive: “I’m living every soldier’s dream,” says Ukrainian fighter

- The Kursk incursion logic