A Wall Street Journal (WSJ) investigation revealed that a seemingly ordinary couple living in the suburbs of Ljubljana, Slovenia, were, in fact, elite officers of Russia's foreign intelligence service, the SVR, hiding under false identities for over a decade.

After their arrest, another couple of suspected Russian agents, known as "illegals," abruptly left their lives in Greece and Brazil, likely called back to Moscow by handlers fearing the collapse of their spy network, according to WSJ.

This news comes as on 11 June, an independent Russian think tank called The Center for Analysis and Strategies in Europe (CASE) proposed that European countries introduce a "relocant card" for Russians, which would simplify their emigration to the European Union and bolster European economy, emphasizing that the majority of Russian "relocants" are wealthy, educated, and anti-war. The name "relocant" applies to Russians who left Russia after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Russian illegals act as ordinary citizens of the country they move into and lead seemingly normal lives: opening businesses, raising children, and paying taxes. However, according to the WSJ, they manage to collect intelligence for Russia, recruit other agents, and build networks of sources, drawing less attention than spies working under diplomatic cover.

Russian spy couple lives 10 years under disguise in Argentina and Slovenia

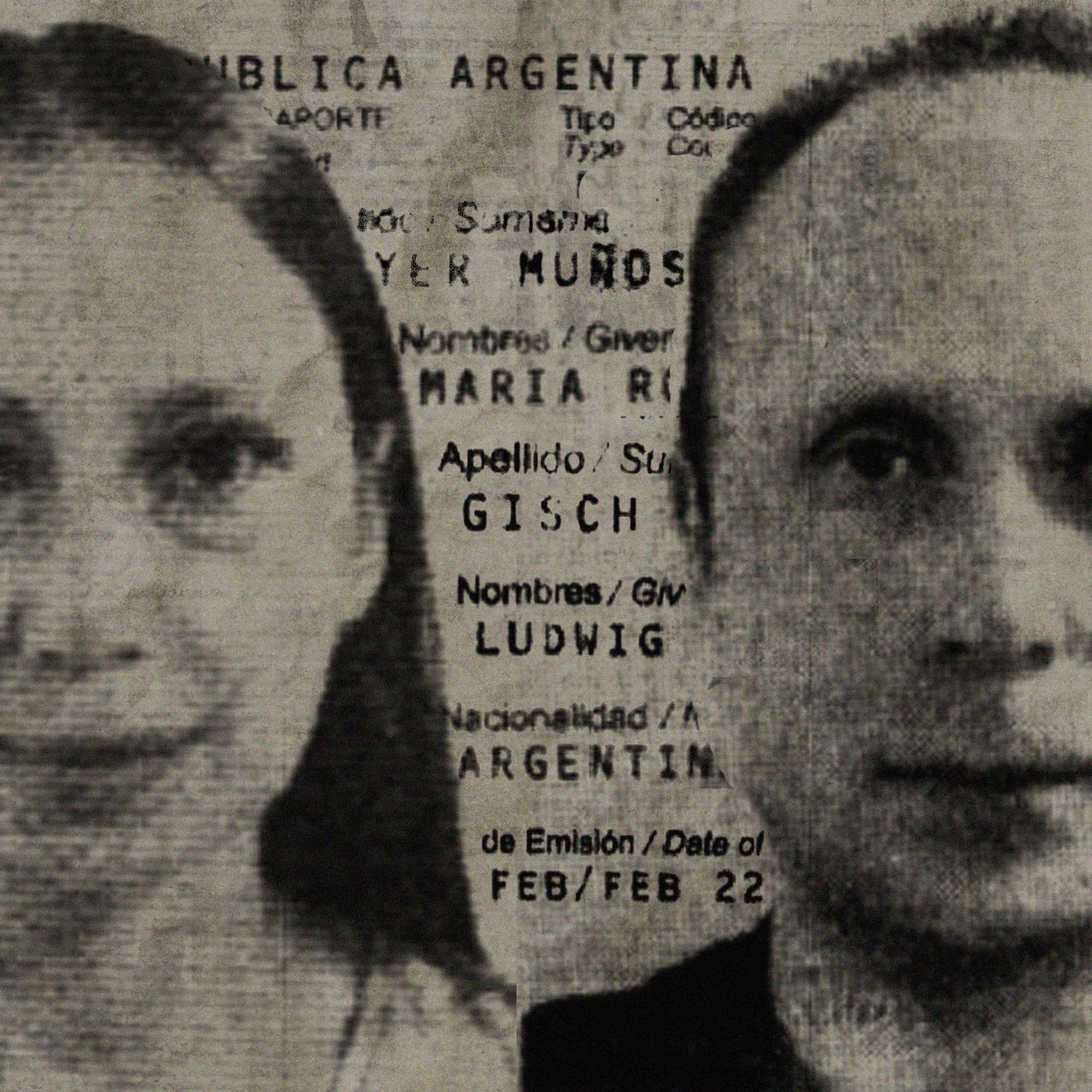

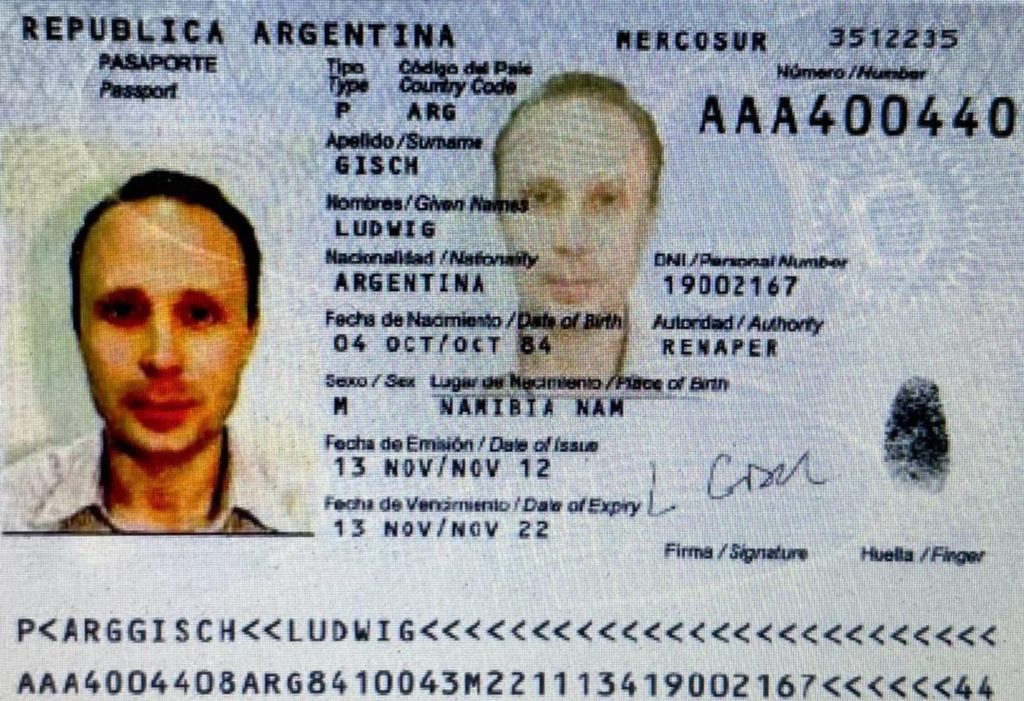

The Russian couple, going by the names Maria Rosa Mayer Muños and Ludwig Gisch, carefully constructed a false identity over a decade, starting in Argentina in 2012 before moving to Slovenia in 2017, according to WSJ.

The couple settled in Buenos Aires, living an inconspicuous life while Mayer Muños attended public relations classes and Gisch opened bank accounts. He registered himself working as a merchant and she - as an events organizer. They had two children and married in a small ceremony in 2015, witnessed by two Colombian citizens.

However, Slovenian officials and Interpol documents revealed their true names to be Artem Dultsev and Anna Dultseva, suggesting they had already been married in Russia before arriving in Argentina, a common practice for "illegal" spies sent abroad.

Before leaving for Slovenia in 2017, the couple made amendments to their marriage certificate and drained their Argentine bank accounts. In Slovenia, they established an IT business and an online art gallery as disguise, filing taxes and maintaining a low profile. On the day Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the couple briefly returned to Argentina to obtain new passports before returning to Slovenia, where the Slovenian authorities caught them.

One of their espionage targets was the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER), Slovenia's only major EU institution. ACER is crucial in coordinating regulatory actions related to electricity and natural gas among EU member states. Following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the agency gained increased prominence as energy became a critical issue for Europe, with Russia using its gas supply to pressure European industry.

Slovenian and Western intelligence officials stated that before their arrest in December 2022, the couple used Slovenia as a base to travel to Italy, Croatia, and across Europe to pay sources and communicate orders from the Kremlin. The couple possessed highly encrypted hardware for secure communication with handlers in Moscow and stored large sums of cash in a secret compartment in their refrigerator.

After the arrest, Russia quickly acknowledged that this couple worked for the SVR and expressed a desire to have them returned. Slovenia was keen on arranging a swift exchange to avoid provoking the Kremlin, but they eventually kept them. The couple could be potentially included in a prisoner exchange with Russia involving imprisoned Americans Paul Whelan, former Marine, and Evan Gershkovich, a Wall Street Journal reporter.

The couple is currently being held in a Slovenian prison while their children are in the care of a foster family. According to Slovenian law, suspects can get up to eight years in jail for espionage.

In contrast to embassy-based operatives who enjoy diplomatic immunity and are often quietly deported when caught, deep-cover agents or "illegals" can face lengthy prison sentences, resulting in years of waiting for release or a prisoner exchange.

Operation Ghost Stories: Russian spies in US

In the US, a case known as "Operation Ghost Stories" revealed that Russian illegals had spent years building seemingly ordinary lives, marrying, buying homes, raising families, and integrating into American society while secretly gathering intelligence and seeking potential recruits. Some even held degrees from prestigious universities, like Harvard, or worked in strategic positions, such as a well-connected consulting firm.

The spies actively collected information, transmitted it to Russia, and engaged in "spotting and assessing" potential targets, including individuals in academia who might one day hold influential positions.

Certain illegals were bringing up their American-born or -raised children as agents, as they would have even deeper cover and be more likely to pass government background checks.

After years of intelligence gathering, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) arrested the illegals on 27 June 2010, and they later pleaded guilty to conspiring to serve as unlawful agents of Russia within the US.

The use of "illegals" dates back to the early Soviet era. These agents played a significant role in stealing American atomic secrets in the 1940s.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, who allegedly worked with illegals during his time as a KGB officer in East Germany, revitalized the program, according to WSJ.

Russian "relocants" in EU countries

The Center for Analysis and Strategies in Europe (CASE), an independent Russian think tank, argues that the war did not provoke a significant anti-regime movement but rather boosted anti-Western sentiment within Russia after the US and EU countries implemented sanctions against Russia, affecting some of its citizens.

As the conflict between the Kremlin and the West is likely to persist for decades, CASE advises Western politicians to view Russian "relocants" as a valuable human resource that can contribute to the economic development of European countries while simultaneously depriving Putin of "significant opportunities."

According to a study conducted by CASE, the majority of Russians who left the country after the start of the full-scale war in Ukraine have higher education or an academic degree. 62 percent of respondents reported monthly earnings of €3,000 ($3200) or more. 79 percent of the Russians who moved to the EU in the past two years oppose Vladimir Putin's policies, while 64 percent support Ukraine.

The think tank proposes that European authorities adopt a strategy to simplify Russian emigration to the EU, granting "relocants" the right to work, open bank accounts, rent real estate, and other economic rights, except for social benefits and privileges, on the condition of their permanent residence in the declared country of stay.

By doing so, CASE estimates that Europe could accept up to 3 million Russians with a capital of at least €400-500 ($429-536) billion within three to five years.

The think tank argues that convincing a significant number of Russians that the Western world does not treat them as enemies is critical to defeating "Putinism," as the report's authors refer to Putin's regime in Russia.

Deep-cover agents or "illegals" are becoming an increasingly valuable asset for the Kremlin, especially as around 700 suspected Russian intelligence officers working under diplomatic cover worldwide were expelled, following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

While Russian spies successfully operated for years under the mask of ordinary civilians, it remains unclear how bringing millions of Russians into the EU, according to the CASE model, would not affect the security of European countries from espionage by Kremlin's agents.

Related:

- Ukraine’s Security Service uncovers 11 Russian spy networks in 2024, agency’s chief says

- Polish court convicts 14 Ukrainians, Belarusians, Russians of spying for Russia

- Al Jazeera: Poland charges members of Russian-linked criminal group spying on Polish aid to Ukraine

- Russian agent spying on air defense positions in Ukraine sentenced to 15 years in prison—SBU

- Spy hideout: where do expelled Russian diplomats resurface?