Founded in 2014 to aid pro-Russian forces in Ukrainian Donbas, the Kremlin-backed Wagner Group has grown into a global network advancing Russian interests. But not only that. The Blood Gold Report, an analysis by independent researchers across countries and think tanks, finds that in countries where Russian mercenaries gain a foothold, they replicate Putin’s vertical of power – including seizing control of the media.

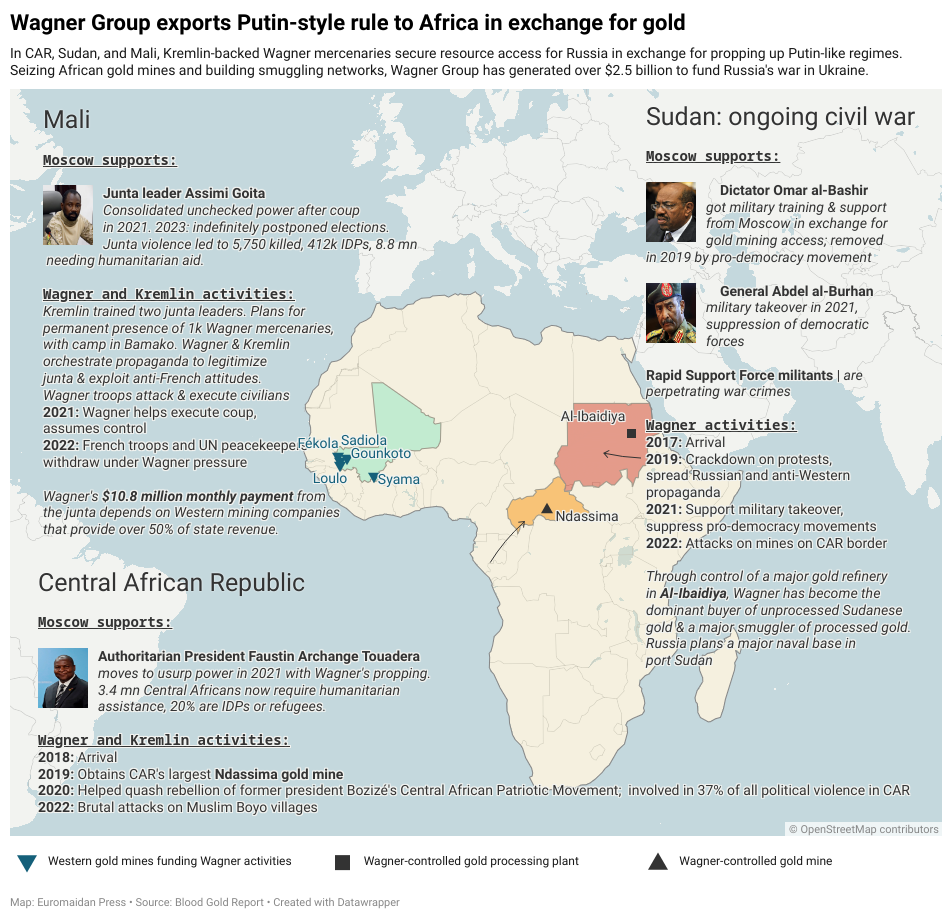

This dynamic is clear in three African nations where Wagner Group has entrenched itself and is siphoning resources: the Central African Republic (CAR), Sudan, and Mali. In each case, Wagner follows a four-part playbook to secure control – suppressing opposition, spreading disinformation, attacking press freedom, and terrorizing civilians. The goal is dependence on Wagner while distracting the West by creating instability.

Security expert Omar Ashour of the Doha Institute explained to Euromaidan Press that Russians target authoritarian-leaning countries and leaders, as well as military coup plotters exhibiting aggressive tendencies, when seeking foreign partners.

“Politically, these regimes want what Putin has and they look at him as a model, not Western democracies. But in doing so, they spark civil wars since segments of African societies want freedom and democracy. So Russia is at war against these democratic movements,” explained Ashour.

Moreover, the active presence of Wagner Group in Africa is generating revenue to sustain Russia’s war effort in Ukraine. A key focus is illicit African gold worth over $2.5 billion since Russia’s 2022 invasion, according to the Blood Gold Report. By propping up regimes and terrorizing civilians, Wagner secures control of mines and refineries in CAR, Sudan, and Mali.

Euromaidan Press sought to analyze why Russia chose these specific countries and how Wagner Group managed to take effective control.

Wagner Inc.

Emerging in 2014 to aid Russia’s operations in Ukraine, the Kremlin-backed Wagner Group has grown into a global mercenary network advancing Russian interests. Initially led by oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin, Wagner provides “security services” and secures resource deals in exchange for propping up regimes and driving instability.

Despite early denials, Wagner’s 2023 failed mutiny revealed its status as an arm of the Russian state, having received almost $1 billion to finance activities. With Prigozhin’s death, Wagner came under tighter Kremlin control.

In just a decade, the group has expanded into a sprawling enterprise commanding tens of thousands of fighters, disinformation infrastructure, smuggling networks, and shell companies, generating estimated revenues of $5 billion between 2017 and 2023, according to the Blood Gold Report.

In Africa, Wagner exchanges military and electoral interference for natural resource access. These Wagner’s activities finance Russia’s war in Ukraine and broader efforts to increase refugee flows and boost pro-Russia parties in Europe.

Why Central Africa?

Ashour explained that Russia targets African countries with traumatic French and British colonial legacies. While the UK was a relatively light colonizer, French rule was violent and bloody. Leveraging Soviet support for African independence struggles, Russia spreads propaganda claiming exclusive credit and demanding African gratitude and influence.

“Though Ukrainian officers trained many African and Middle Eastern military personnel as part of the Soviet Union, Russia omits this fact. Instead, Russia claims sole credit for Soviet aid, arguing that African nations owe Russia gratitude,” the analyst said.

Russians ally with authoritarian regimes and leaders in Africa who see Putin as a model, not Western democracies. This sparks civil wars as parts of those societies want freedom, putting Russia at war with democratic movements. Militarily, Wagner helps regimes fight these internal enemies.

“Wagner Group promises experienced fighters trained in Russia who know how to win dirty wars and prop up shaky regimes – for cash or other perks. They act as an extension of the Russian state rather than a private military company,” explained Ashour.

Wagner in CAR

Wagner has used CAR as a laboratory to incubate its strategy for expanding in Africa, providing proof of concept for a playbook later deployed to destabilize other nations.

Since achieving independence from France in 1960, CAR has faced perpetual cycles of coups and ethnic-religious violence stemming from weak central authority. President Faustin Archange Touadera was elected on a promise of interfaith peacebuilding in 2016 yet relied on dispensing positions and weapons to allies to hold power amid ongoing crises and threats from rival factions.

Since Touadera survived a major challenge in early 2021 thanks to Russian support, he has moved decisively to consolidate control and impose authoritarian policies – including overseeing a highly questioned referendum extending presidential terms to seven years with no term limits.

Russia began engaging CAR in 2017 after Touadera took power. In late 2017, Moscow got a UN exemption to send 5,000 Russian-manufactured assault rifles, machine guns, pistols, and rocket launchers to CAR.

Relations were formalized in 2018 when Foreign Minister Lavrov met Touadera delegates and signed a military agreement for Russian training and “instructors.” While officially for mutual defense, the deal unofficially gave Touadera political/military protection via Wagner forces in exchange for Russian gold mining rights and other revenue sources.

Step 1: Suppressing opposition. This is the first and most important component of Wagner’s African playbook. The mercenaries first arrived in CAR in 2018, referred to by Russian and CAR authorities as “armed specialists” and “civilian instructors.” Ahead of CAR’s disputed 2020 election, former President Bozizé united armed groups into the Central African Patriotic Movement (CPC), clashing with Touadera’s weak government forces.

After Touadera claimed victory, the CPC attacked the capital city Bangui, but Wagner mercenaries helped repel them alongside UN and Rwandan troops. Wagner Group then enabled Touadera to retake cities and crush the CPC rebellion by May 2021, later implicated in assassinating a CPC demobilization leader Zakaria Damane threatening their profits. His death renewed violence.

Research by the Armed Conflict Location Event Data Location (ACLED) shows that Wagner Group’s presence perpetuated violence, directly involved in 37% of all political violence in CAR from December 2020 through May 2023.

Step 2: Spread disinformation. In CAR, Moscow funds a propaganda radio station supporting Touadera. Wagner also benefits from celebrities like Blaise Kossimatchi, who expresses unwavering support for Russia and wears “Je suis Wagner” t-shirts. Kossimatchi’s 45,000-member organization has pressured Touadera opponents, including the constitutional court chief, who criticized a referendum enabling unlimited presidential terms. Through propaganda, Wagner normalizes its presence while sowing suspicion of critics.

Step 3: Silence independent media. In 2018, three Russian journalists investigating the activities of Wagner mercenaries were murdered by assailants in CAR, suspected to be associated with the Kremlin. In 2022, journalist Jean Sinclair Maka Gbossokotto, an outspoken critic of the Kremlin’s meddling in CAR, died under suspicious circumstances after meeting with a Russian contact.

Step 4: Terrorize civilians. The most devastating component of Wagner’s African playbook, refined in CAR, is terrorizing civilians into submission. In December 2021, Wagner mercenaries attacked Boyo villages to punish Muslims collectively. They committed murder, hostage-taking, looting, destruction of property, forced displacement, and sexual violence – acts tantamount to ethnic cleansing. A UN investigation reported at least 20 civilians killed, but deaths may have been over 100.

Due in part to Wagner’s brutality, 3.4 million Central Africans now require humanitarian assistance, with one in five internally displaced or a refugee.

Since arriving in the CAR, the Wagner Group grew from 175 mercenaries in 2018 to 2,600 personnel by 2021. The Kremlin-backed private army now commands the Central African military and ex-rebel ”self-defense groups.” Through this expanded presence, Wagner sits atop the command chain.

Wagner in Sudan

Since independence from the UK in 1956, Sudan’s democratic institutions have been overthrown by military force three times over the 20th century.

Some democratic hope emerged in April 2019 when a civil society coalition called Forces of Freedom and Change removed longtime dictator Omar al-Bashir. The pro-democracy alliance established a transitional government with the military to guide Sudan towards democracy.

However, moves to confiscate assets gained under al-Bashir threatened military economic interests in various companies.

Following a failed 2021 coup, General Abdel al-Burhan dissolved the civil transitional government and detained officials, with initial support from the Rapid Support Force (RSF) military offshoot. After relations deteriorated, al-Burhan declared the RSF rebels in April 2023, sparking ongoing civil war.

Moscow first engaged the al-Bashir dictatorship in 2017 when the US relaxed some sanctions on Sudan for human rights progress, though maintained restrictions on figures like al-Bashir for the Darfur genocide. In response, al-Bashir deepened ties with Russia for “protection against US aggression.”

Sudan was already Africa’s third-largest Russian weapons importer. The new agreement brought al-Bashir increased military support and training from Russia in exchange for gold mining access.

Al-Bashir’s fall in April 2019 was a setback for Moscow’s ambitions, but only temporarily stalled Kremlin projects in Sudan. Evidence suggests Wagner-linked Russian Il-76 planes delivered missiles to RSF days before it launched attacks in April 2023, capturing and massacring in western Darfur towns.

Per the US State Department, the RSF and militias were perpetrating “rape, murder, ethnic killings” in Sudan’s civil war.

Step 1: Suppress the opposition. Upon arriving in Sudan in 2017, Wagner mercenaries advised al-Bashir on suppressing protests with “minimal but acceptable loss of life.” In January 2019, they assisted in cracking down on growing anti-government demonstrations.

After al-Bashir’s fall, Wagner operatives maintained contact with military elements. They actively supported the 2021 military takeover led by al-Burhan and helped security forces suppress pro-democracy movements throughout 2022.

Step 2: Spread disinformation. In 2019, leaked documents revealed Wagner’s disinformation tactics in Sudan. The mercenaries advised al-Bashir on rhetoric to prevent a “color revolution” and boost his reputation, including accusing protesters of being foreign agents who committed arson and theft.

After al-Bashir’s removal, Wagner forces persisted, using Facebook pages to spread Russian “humanitarian aid” propaganda, spread anti-Western sentiment, and disseminated Russia Today and Sputnik news articles.

Step 3: Silence independent media. After al-Bashir’s overthrow in April 2019, Sudanese journalists briefly enjoyed a respite from censorship. Since the 2021 coup, attacks on reporters by security forces have intensified.

The actions of the al-Burhan junta in Sudan align with patterns observed in other Wagner-influenced nations. This closely resembles advice previously provided by Wagner strategists to the al-Bashir regime, emphasizing the replication of Putin’s vertical of power, including gaining control over the media landscape.

Step 4: Terrorize civilians. Wagner forces have aided Sudan’s authoritarian regimes in suppressing any democratic impulses. Wagner’s reconnaissance preceded a brutal crackdown – al-Bashir’s forces killed over 120 and injured 900 civilians in June 2019.

Wagner is also believed to have perpetrated attacks on mines along the Sudan-CAR border in March-May 2022, killing dozens of miners. The current civil war exacerbated by Wagner support has killed 9,000 and displaced millions.

In Sudan, Wagner maintains a discrete profile focused on training the military and backing Kremlin-friendly forces, with evidence of involvement mostly from social media. Sudan is vital for supplying other Wagner African troops, so missions reinforce each other, complicating any move towards democracy in one country while others remain under Moscow’s influence.

Wagner in Mali

After independence from France in 1960, Mali underwent a period of one-party socialist authoritarianism and military dictatorship before turning to multiparty democracy in 1992. The country was considered “Free” by Freedom House in 1995 and observers in 2006 still considered Mali an example to neighboring states. However, in 2012-2022 Mali suffered three coups.

The disputed 2020 elections led to Colonel Assimi Goita‘s takeover. After the interim authorities decided to reshuffle two military appointees, Goita led a second “coup within a coup,” overthrowing the transitional government in May 2021. Despite pledging an eventual democratic transition, Goita’s junta instead consolidated unchecked power.

Today, Freedom House rates Mali as “not free.” The country is plagued by armed Islamist violence, fractured state authority, paltry local services, arbitrary decision-making by the ruling military junta, suppression of political opponents, summary executions of prisoners, 5,750 civilians killed between January 2022 and March 2023, 412,000 individuals displaced, and 8.8 million requiring urgent humanitarian assistance.

Despite initial promises, the junta indefinitely postponed elections in August 2023, citing “technical reasons.” The Wagner Group’s growing influence raises doubts about a swift return to democracy in Mali.

Pre-coup, the Kremlin developed military ties, training two junta leaders in Russia. Post-May 2021 coup, Wagner assumed control.

A reported $10.8 million monthly Wagner deal for 1,000 mercenaries reflects intentions for a permanent presence. Satellite imagery reveals Wagner’s growing Bamako camp, including barracks and housing. Despite Prigozhin’s death, construction continues – reaffirming Russia’s unchanged ambitions in Mali.

Step 1: Suppress the opposition. Wagner has been key to displacing the junta’s rivals. The main ones were French and UN forces. France withdrew 2,400 troops in early 2022 after Wagner’s arrival. Wagner also catalyzed the removal of the 13,000 soldiers of the UN MINUSMA peacekeeping force. Since international forces left, Wagner has focused on the restless north, leading to civilian atrocities.

Step 2: Spread disinformation. Wagner and Russia orchestrated propaganda in Mali to legitimize the regime, garner sympathies, and exploit anti-French attitudes.

Pro-Kremlin groups like Salafi imam Mahmoud Dicko’s acted as early content distributors. Dicko’s group allegedly used bot farms to fake 8 million petition signatures for Russian intervention.

Before the 2020 coup, purported pan-African protests echoed pro-Russia and anti-French views, likely Russian-financed. In August 2022, Wagner mercenaries were filmed burying bodies near Gossi base in northern Mali, which France had just transferred over. A fake Twitter account later accused France of the killings. Paris claimed this was a Wagner ploy to falsely portray the deaths as a French atrocity to damage their reputation.

Step 3: Silence independent media. Since Wagner’s arrival, attacks on press freedom have rapidly increased in Mali. In February 2022, Mali banned two major broadcasters, Radio France International and France 24. High-profile kidnappings and killings of journalists have persisted after expelling international media. In November 2023, a journalist was killed and two others kidnapped. Malick Konaté, who criticized Wagner, has received death threats since 2020.

Step 4: Terrorize civilians. Wagner forces have committed up to 300 confirmed violent acts against civilians in Mali, with a disturbing 69% of Wagner missions targeting noncombatants.

Arbitrary arrests, looting, and cattle theft are rampant. Wagner massacred 50 civilians in Hombori. From February to March 2022, 50+ people went missing, and 35 charred bodies were found after the army and Wagner raids in Segou. In March 2022, Malian troops and Wagner executed 500 people over suspected links to Islamists.

Despite Mali’s official denials, Wagner has a growing presence there. Estimates put personnel at 1,200-1,650. The group directly engages alongside Malian forces and militias in the north and is involved in 90% of central Mali operations.

Across CAR, Sudan, and Mali, Wagner’s playbook has not brought greater security but rather enabled authoritarian entrenchment, democratic erosion, civil society devastation, and civilian brutalization. Beyond empowering client regimes, the turmoil allows Wagner to profit – revenue generation is the primary motive for their African adventurism. Gold extraction is vital to this vast plunder enterprise.

Russia replaces Wagner Group with state-controlled forces in Africa

Omar Ashour explains that the Putin regime is taking a strategic, long-term approach toward Africa.

“NATO is succeeding in the Baltics with Finland and Sweden joining, and in the Mediterranean due to Türkiye and Greece, but Russia is counter-reacting via involvement in Syria, Libya, and other countries in the region,” said Ashour.

And despite Prigozhin’s death, new projects continue, as the Kremlin remains fixed on Africa long-term.

Despite Wagner Group founder Prigozhin’s death, Russian projects in Africa continue. The Kremlin remains fixed on Africa for the future, recently replacing Wagner there with state-backed pseudo-private military companies Redut and Convoy.

According to the WSJ, Redut is financed by oligarch Gennady Timchenko and Convoy by Arkady Rotenberg. The new mercenary structure is headed by Russian Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov and overseen by intelligence official Andrey Averyyanov of the Main Intelligence Directorate.

In September-August 2023, a Russian official delegation featuring Yevkurov, Averyanov, Redut leader Konstantin Mirzayants, and former Wagner Africa commander Konstantin “Mazay” Pikalov visited Libya, Burkina Faso, Mali, and CAR.

The shift demonstrates that Russia now seeks more centralized Africa control via state channels rather than loosely-managed mercenaries.

“And then Russians renamed the organization Africa Corps. Tellingly, the Nazi Wehrmacht organization operating in Africa, was named just that, Afrika Korps. [We see the influences of] one of the Wagner Group’s founders, Dmitry ‘Wagner’ Utkin, who was also a Nazi sympathizer,” noted Ashour.

In conclusion, the Wagner Group applies an authoritarian playbook across Africa to install Putin-style regimes – suppressing opposition, attacking press freedom, spreading disinformation, and terrorizing civilians. This systematic approach seen in CAR, Sudan and Mali not only empowers strongmen but erodes democratic values.

As Russia swaps Wagner for state forces like Redut and Convoy, it entrenches ambition for Putin-esque rule across Africa, posing a major threat to rights, governance, and stability that demands global vigilance.

Read more:

- Wagner defector exposes Russia’s Donbas ruse, false-flag ops in bombshell interview

- UK intel: Russia officially recognizes Wagner Group veterans

- “They just did it for fun”: Ukrainian survivors detail Wagner group horrors

- UK declares Russian Wagner Group a terrorist organization