A new study by researchers Tatyana Deryugina from the University of Illinois, Yuriy Gorodnichenko from the University of California, Berkeley and Ilona Sologoub, VoxUkraine suggests that many top Western universities continue to promote biased and distorted narratives about Russia in their Slavic studies programs.

The researchers analyzed the course descriptions from 13 leading US universities for academic years 2021/22 and 2022/23. They focused on courses related to the literature, culture, and history of Russia, Ukraine, and other Eastern European nations.

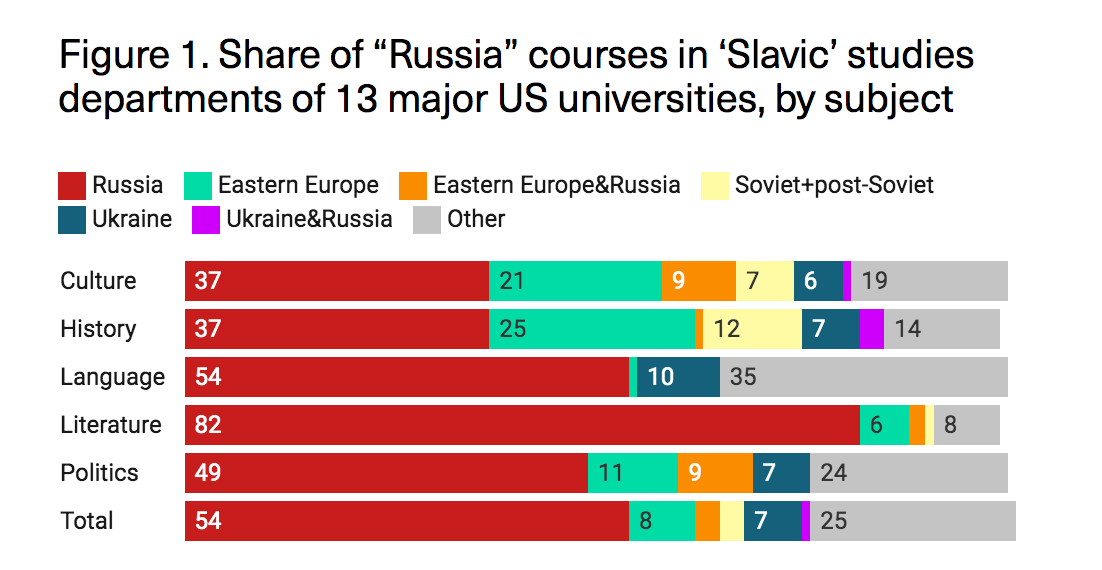

The study found that courses focused solely on Russia vastly outnumbered those on other countries in the region. Out of 425 total courses examined, half (215) were exclusively about Russia.

This aligns with previous research showing Russia’s oversized footprint in Slavic studies departments. The researchers found that “Slavic” studies departments at major US universities are heavily focused on Russia, with Russian literature courses making up over 80% of literature offerings.

Overall, around a third of history courses cover solely Russia, while many additional courses group Russia together with other regions like Eastern Europe.

In contrast, the researchers found Ukraine is almost non-existent in course offerings. Before 2022/23, virtually no courses covered solely Ukrainian history or literature. Even with increased Ukraine content in 2022/23, Russia-focused courses grew in parallel.

In contrast, the researchers found Ukraine is almost non-existent in course offerings. Before 2022/23, virtually no courses covered solely Ukrainian history or literature. Even with increased Ukraine content in 2022/23, Russia-focused courses grew in parallel.

Courses on literature: superlatives for Russian lit

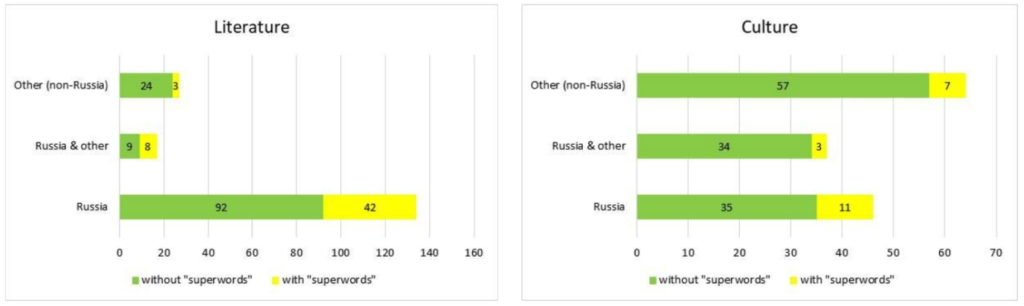

But beyond the quantitative imbalance, the researchers identified significant qualitative biases favoring Russia in the course descriptions. They looked for “superlatives” like “masterpiece,” “genius” and “great” used to describe Russian literature and culture. About 31% of Russian literature course descriptions contained such glowing language, compared to only 11% for non-Russian literature.

According to the researchers, “Russia is portrayed as a country of ‘great culture’ and ‘great literature’ possessing ‘unique’ features.” Meanwhile, other Eastern European cultures are often described in more modest terms.

“For instance, compare ‘notable artistic skills’ (Serbia) or ‘a delightful act of defiance’ (Poland) with ‘literary masterpieces that transcend time and place’ (Russia),” the researchers write.

The researchers state that Western universities continue to imprint in students’ minds the idea of “great Russia” and “unique culture,” not only by offering many more courses about Russia than about other countries in the region but also by promoting Moscow-centric narratives.

Because of this, the researchers say students do not understand what real Russia is – “an empire that wreaks havoc around the globe but is corrupt and weak behind the macho facade.”

“The cost of imprinting this ‘great Russia’ narrative comes in things big and small: businessmen selling weapon parts to Russia or limiting the use of Starlink in Ukraine, politicians trying hard to ‘save Putin’s face,’ philosophers urging Ukraine to surrender, and even the Pope praising imperialist tsars to Russian youth. In light of how much pain Russia causes in Ukraine and elsewhere, all of these things are absurd and cruel but they are consistent with the thinking that Russia must be respected because it is ‘great,’” the researchers write.

Unfortunately, the researchers say universities continue to nurture new generations of “Russia-Verstehers.”

Courses on culture: using Nobel Prizes as a comparison baseline

The researchers report that course descriptions in the “Culture” category are more balanced – only 14% contain “super words.” However, for Russia-focused courses, this share is 24% versus 11% for non-Russian cultures courses. The researchers also looked at the number of courses devoted exclusively to a single artist/writer and found quite a few in the “Literature” category – 49 courses on Russian literature, 1 on Serbian, and 2 on Polish. In the “Culture” category there are three such courses for Russia and one for Poland.

The researchers suggest Nobel Prizes in Literature can serve as an imperfect but useful metric for comparing literatures, cultures, histories, etc, since the prizes represent quality. They point out that as of 2023, a number of Eastern European authors have received the Nobel Prize in Literature, including 6 Poles, 5 Russians, 1 Hungarian, 1 Bulgarian, 1 Czech, 1 Romanian, 1 Yugoslav, 1 Belarusian. Yet few courses single out Polish writers or praise them in the same way as Russian writers.

The researchers found four courses in the “Literature” and “Culture” categories that equate medieval Rus and Russia, and five courses in each category that equate Russia with the USSR. One course even places Chernobyl in Russia.

Courses on history: blending Russia with the Soviet Union

The researchers took a unique approach to analyzing history course descriptions. While they continued to search for terms like “superpower,” “world power,” and “heroes,” their primary focus was on uncovering misleading narratives.

In their findings, they identified instances of Rus’ inclusion in Russian history (6 courses, including one with “Kievan Russia,” which they deemed inaccurate). This inaccuracy arises from the historical fact that Rus refers to the medieval state centered in Kyiv, which is distinct from modern-day Russia. Moreover, they noted the conflation of Russia with the USSR in 10 courses.

They also identified contemporary manipulations, such as framing the “unification of the Russian state by Muscovy” as a forceful occupation of other lands by the Grand Duchy of Moscow, referencing the Great Patriotic War as the Nazi-Soviet part of World War II, and using terms like “conflict in Ukraine,” “Russia-Ukraine conflict,” and “events in Ukraine” as euphemisms for the Russian war of aggression, among other findings.

Examples:

- One course on Eastern Europe mentions “70 years of departure from Western values and ultimately an attempt to return to them” which implies Eastern Europe consciously renounced Western values and returned to communism after World War II, completely ignoring that Britain, the USA, and the USSR agreed in 1945 at Yalta to leave Eastern European countries under Soviet rule and de facto occupation.

- Another course assumes that “church policy and inter-Christian conflicts play a leading role in the politics of modern Ukraine.” Although there was tension between the Catholic and Orthodox churches in Ukraine in the 16th-19th centuries, this has not been the case since the 20th century, and certainly not in modern Ukraine. The only “church conflicts” in Ukraine today are tensions between the Russian-affiliated Orthodox Church in Ukraine and other Ukrainian denominations, the researchers say.

- Another course describes Ukraine as a “30-year-old nation,” disregarding the fact that the modern Ukrainian nation, like most European nations, emerged in the 19th-20th centuries. In 1992, Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk received statehood symbols from the government-in-exile of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, formed in the early 20th century. The researchers note that Ukrainians sought independence in the 1910s-1920s and during World War II, inspired by the earlier Cossack state, which considered itself the successor of the Kingdom of Rus.

- The researchers critique a course description stating: “In three centuries [1613-1917] [the Romanovs] transformed [Russia] from a landlocked country populated mostly by ethnic Russians into a huge, Western-focused, multiethnic empire ruling over more than 100 million people across some 8.6 million square miles.” They call this sentence a collection of imperial myths. The researchers explain that until the early 18th century, the country in question was called Muscovy and was inhabited mostly by Finno-Ugric tribes with a small Slavic population share. They state that the notion of “ethnic Russians” is problematic even today, and did not exist at all in the 17th century. The researchers also question the supposed Western orientation of the Russian Empire, saying it opposed itself to the West both militarily and culturally. Finally, they argue that the large territory and population becomes much less impressive considering it was achieved through continuous wars and genocides, which continue today.

What are the sources of pro-Russian bias?

The researchers discuss three potential sources of pro-Russian bias in academia: money, inertia, and ideology. From conversations and feedback on their first article, they deduced these three main reasons for the lingering bias.

- Russia has invested billions of dollars in promoting “its” literature and art abroad, as well as its view of Eastern European history. They say Russia still heavily promotes false historical and geographical narratives, influencing textbooks and maps. The researchers argue Russia invests billions in foreign think tanks and politicians to help disseminate its viewpoint of Russia as a “force to be respected and feared.”

- Russian propaganda is spread by many respected personalities (e.g. Noam Chomsky and Jeffrey Sachs), which is, though, not a new phenomenon. They give the examples of George Bernard Shaw, who wrote about the “hopeful and enthusiastic working class” in March 1933 during the Kremlin-induced Holodomor famine, and Albert Einstein, who praised the USSR for protecting Jews despite ongoing Soviet anti-Semitism. These examples illustrate the effectiveness of Russian propaganda, the researchers say, which has deceived not only foreigners but even some who emigrated from Russia. They cite poet Joseph Brodsky, who despite fleeing Soviet persecution proceeded to deny Ukrainians the right to independence (in particular, with his infamous poem “On independence of Ukraine.”).

- Many Western intellectuals have been influenced by the appeal of communist ideology championed by the USSR. They argue that while communism may seem attractive in theory, its real-world application has consistently resulted in dictatorships, labor camps, violence, and widespread famine. The researchers suggest that intellectuals often choose to heed voices like Walter Duranty, a Pulitzer Prize winner for disseminating false Soviet propaganda, rather than heeding truth-tellers like Gareth Jones, who reported on the Holodomor famine.

The researchers believe the situation needs to be changed, despite the challenges of money, inertia, and ideological bias. They say the role of intellectuals is to disseminate new ideas when old ones fail. Specifically, they advocate studying Russia in the “empire and” rather than “empire but” paradigm, recognizing it as a typical brutal imperial power.

The researchers argue this Moscow-centric academic lens has contributed to misunderstandings of Ukraine among Western experts and media. They advocate for more resources and focus on Ukrainian, Polish, and other Eastern European studies to provide balance. In their view, proper commitment to Ukrainian studies could have helped prevent the current Russo-Ukrainian war. “It would be strange if American students studied the history of India solely from British sources, right?” the researchers note.

“There is no lack of qualified historians, linguists or economists from these countries, many of whom work at US or European universities. There is no lack of studies that tell the truth about the nature of Russia either (e.g. publications by Serhiy Plokhy or Timothy Snyder). One only has to recognize the unpleasant truth: that the ‘imprint’ of the ‘great Russia’ is false,” the researchers conclude.

Related:

- Ukrainian scholar to the West: Cut academic ties with Russia

- Like KGB in Soviet times, FSB ‘curators’ assuming expanded role in Russian academia

- How a university in Lviv has revolutionized higher education in Ukraine

- Academia again serves state ideology as Russia convicts Ukrainian

- Russia’s soft power empire pivots to Global South