In a March 2022 column, historian Heinrich August Winkler wrote in the weekly German newspaper Die Zeit, he listed the striking parallels between Hitler’s policies in 1938 and 1939 and Putin’s policies since 2014. Among them:

- Hitler’s “Anschluss” of Austria.

- Hitler’sannexation of the Sudetenland to the “Greater German Reich.”

- Hitler’s orchestration of the secession of Slovakia from the Czechoslovak Republic and the “dismemberment of the rest of Czechoslovakia.”

- Putin’s annexation of Crimea.

- Putin’s separation of substantial areas of the Donbas from Ukraine.

- Putin’s full-scale invasion of and ongoing unprovoked and genocidal war against the “Slavic brother people” of Ukraine.

I. Putin and Hitler: War

The war in Ukraine is Putin’s war, just as World War II was Hitler’s war.

Before his assassination on 27 February 2015, the Russian dissident Boris Nemtsov had collected material for a report on Putin’s readiness for war. It was published posthumously under the title “Putin War,” by the Free Russia Foundation on 25 May 2015. It turned out to be prophetic cognition.

Hitler longed for war. In the war of conquest against the Soviet Union, he saw his historic mission. Only four days after his appointment as Reich Chancellor on 30 January 1933, Hitler spoke to military officers about the conquest of “living space in the East.”

Putin’s war, like Hitler’s war, is a war of aggression, which is prohibited under modern international law. The legal prohibition of wars of aggression was standardized after the First World War.

Putin dubbed his war against Ukraine “a special military operation” and criminalized the use of the word “war” to avoid violating the international law banning wars of aggression.

Hitler staged a pretext for his invasion of Poland by simulating a Polish raid on the Gleiwitz radio station on 31 August 1939). Putin, however, needed no alleged provocation.

The aggressors’ declarations of war

The televised speech Putin made in the early hours of 24 February 2022, when the Russian invasion had already begun, justifying the invasion of Ukraine he had ordered, is reminiscent of Hitler’s speech to the German Reichstag on Sept. § 1939, broadcast on Greater German Radio on the occasion of the German invasion of Poland.

In this speech, Putin once again resorted to the “Big Lie” that he has been repeating in Hitlerian fashion for years, namely that the Ukrainian government had “mistreated and murdered” the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine. Hitler justified the attack on Poland by asserting that the German minority living in Poland had been “disenfranchised” and “mistreated.”

Putin admired Goebbels, the master of the “Big Lie“: “He prevailed, he was a gifted man,”| Hitler said.

In the spirit of Hitler, Putin’s speech on 24 February 2022, called for “the cohesion of society, its willingness to consolidate and join all forces to move forward.”

In Hitler’s speech on 1 September 1939, it sounded like this: “If we form this community, closely conspired, determined to do everything, never ready to capitulate, then our will will master all adversity.”

Putin admired Goebbels, the master of the “Big Lie”: “He prevailed, he was a gifted man.“

Drive for conquest – undisguised and veiled

Unlike Adolf Hitler, who made no secret of his imperialist intentions, Putin initially veiled his project of restoring the Russian Empire. At the beginning of his rule, on 30 January 1933, Hitler concealed his will to war behind assurances of peace. One example was his” Peace Speech” on 17 May 1933. But he had already sketched out his imperial project in writing his book “Mein Kampf” in 1925.

Vladimir Putin, 18 months into his first tenure as Russian president, earned a resounding applause spanning all parties from German Bundestag members of parliament after his speech to the elected body on 25 September 2001. Putin spoke of the “spirit of these ideas,” namely, “democracy and freedom,” which had taken hold of the Russian citizenry. He also spoke of the “construction of a common European house,” in which Europeans would not be divided into Eastern and Western, Northern and Southern. “As to European integration,” he said, “We don’t just support these processes, we see them with hope.”

Either Putin meant what he said in 2001 and turned 180 degrees out of disappointment at the rejection of his offer—building a common, pan-European security system and free trade area “from the Atlantic to the Pacific”—or he deceived the world from the beginning,“ once KGB always KGB,” to gradually put his imperial intentions into practice behind this rhetorical veil without having to fear much resistance.

Only six years later, at the 43rd Munich Security Conference on 12 February 2007, Putin shocked the European participants with an aggressive speech in which he announced a radical change of course: The first implementation of his new anti-Western policy followed in August 2008 with the Five-Day War against Georgia. In 2014, Putin manifested his revisionist intentions with the bloodless yet illegal annexation of Crimea. But he still denied the covert use of regular Russian soldiers in the hybrid war he unleashed against Ukraine in the Donbas that same year. In an essay published under his name in July 2021, in which he described Ukraine as an “anti-Russia” built up by the West, Putin revealed his true face through his half-open visor—only to drop all veils from his revanchist, neo-imperialist project by his military invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

“Interference” from outside: Different rhetoric

Addressing the “collective West,” on the day of the invasion, Putin threatened: “Now a few important, very important words for those who might be tempted to interfere from the side. […] Whoever tries to obstruct us […] must know that Russia’s response will be immediate and will lead to consequences the likes of which they have never experienced in their history.” Since the failure to take Kyiv in a blitzkrieg, Putin has blatantly and consistently threatened to use nuclear weapons.

Hitler, in his declaration of war on 1 September 1939, feigned “incomprehension” that the “Western European states”—meaning Britain and France—were “interfering in the conflict.

Hitler and Putin: commanders-in-chief and major war criminals

After the death of the second president of the Weimar Republic, Paul von Hindenburg, on 2 August 1934, the Führer Adolf Hitler assumed supreme command of the Reichswehr, the Weimar Republic’s Armed Forces, The Reichswehr swore personal allegiance to Hitler, breaking historical precedent that the military defended the Weimar Constitution.

On 4 August 1938, Hitler personally assumed command of the entire Wehrmacht, the unified armed forces of the Nazis, by Führer Decree.

As the problems on the Eastern Front increased in late autumn 1941, there were frequent disagreements between Hitler and the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch. On 19 December 1941, Hitler accepted his resignation and assumed the supreme command of the Army

According to the Russian Constitution, the President of the Russian Federation is the supreme commander in chief of the Russian Armed Forces.

After the failure of the blitzkrieg against Ukraine, Putin pulled the operational supreme command to himself in August 2022, according to CNN. The American news organization reported that Putin was personally commanding the generals on the Ukrainian front. By changing the chain of command, he was responding to “dysfunctional command structures that have plagued the Russian army since the beginning of the war.”Putin had bypassed Defense Minister Sergei Šojgu, who had lost Putin’s trust at the end of August 2022, according to the US think tank Institute for the Study of War.

II. “Putinism” – Russian Fascism

Fascism – an errant term

For more than 90 years, the content and scope of the concept of fascism have been debated. No other “ism,” as Roger Eatwell stated, has produced such contradictory interpretations as fascism. Eatwell considers it useful to use the term “fascism” as a heuristic construction that enables the recognition of “relations of kinship.”

For Putin, a “fascist” is simply someone who opposes him. That is practically all Ukrainians who do not want to give up their Ukrainian identity. The Secretary of the Russian Security Council, Nikolay Patrushev, claims that Russia is under attack from “neoliberal fascism”(!)

The term “fascism” is generally used non-specifically, i.e., detached from its Italian original and also from its various historical national manifestations. On the one hand, it has taken on an almost metaphysical meaning—as the epitome of evil—but also a banal one as an insult to opposing groups and persons.

For Putin, a “fascist”—completely independent of the ideological affiliation of the person in question—is simply someone who opposes him, says the American historian Timothy Snyder. That is all Ukrainians who do not want to give up their Ukrainian identity, and their Ukrainian language and who refuse to accept Russian citizenship.

As an example of the shift in the conceptual coordinate system, Snyder cites the claim by the Secretary of the Russian Security Council, Nikolay Patrušev, that Russia is under attack from “neoliberal fascism.” It is important, Patrušev said, to understand this ideological dimension of global aggression against Russia.

The deputy head of the Russian Mission to the United Nations, Dmitry Polyansky, convened an informal meeting of the UN Security Council on July 11, 2022, to denounce alleged “neo-Nazism” in Ukraine—and to justify the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine to the world public. The theme of the event was: “Neo-Nazism and Radical Nationalism: Examining the Origins of the Crisis in Ukraine.” The West, he said, had studiously failed to take note of the (alleged) crimes of Ukrainian neo-Nazis in the Donbas.

While in Marxist theories of fascism, German national socialism is classified as a form of fascism:” Hitler fascism,” militant “anti-fascists” use “fascism” and “Nazism.”. Russian propaganda differentiates just as little between “fascism” and “Nazism” when defaming Ukraine.

“Ruscism” – Russian fascism

Behind the mask of officially proclaimed anti-fascism, Putin’s Russia is hiding a new fascism: “Ruscism.” The term is a fusion of the words Russian and fascism. “Ruscism” from Russian “russkiy fashizm” is the popular name for specifically Russian fascism. It is an alternative to the term “Putinism.”

“Putinism” is an outwardly aggressive and inwardly repressive, neo-imperialist, hypertrophied nationalism. Those are also elements of fascist Italy and National Socialist Germany. The decisive difference to Hitler’s fascism is that Putin’s fascism does not include programmatic anti-Semitism.

The Verchovna Rada, the parliament of Ukraine, with the votes of 281 deputies, characterized the political system in Russia as “Russian Fascism” or Ruscism. This declaration was addressed to the United Nations, the European Parliament, the Parliamentary Assemblies of the Council of Europe, the OSCE, NATO, and many governments and national parliaments with the call to support the condemnation of the ideology, policy, and practice of Ruscism.

The explanatory note accompanying the declaration reads: “…The cruel, unprovoked war of the Russian Federation against Ukraine has revealed to the whole world the true character of V. Putin’s political regime—as a neo-imperialist, totalitarian dictatorship that has inherited the evil practices of the past; it embodies the ideas of fascism and Nazism in the modern-day version of Russian fascism.”

The “Z” symbol was painted on all the gates in Ivanivka village, which was occupied by Russian troops in March 2022. 1 June 2022, photo by Euromaidan Press.

An official emblem was created especially for the war of extermination against Ukraine: a Latin “Z,” which sensibly resembles an inverted “half swastika.”

“We Should Say It. Russia Is Fascist,” wrote Timothy Snyder in The New York Times on 19 May 2022. In an interview with Jochen Bittner of the German weekly Die Zeit, Snyder said:

“The Germans were always very interested in Ukrainian fascism, which was a completely marginal phenomenon, and completely disinterested in Russian fascism, even though it was increasingly taking possession of the Russian state.”

On Twitter, Snyder had previously written, “For thirty years, Germans lectured Ukrainians about fascism. When fascism actually came, Germans funded it while Ukrainians died fighting it.”

In an op-ed for The Moscow Times, Snyder lists three criteria for his finding that Russia is a “state with a fascist government”:

- The cult of leadership around Putin.

- The cult of the dead around the victims of World War II.

- The cult of the past, around a golden age of imperial greatness, must be restored with the help of healing violence.

“Fascism as an idea was not defeated […] It returned…,” Snyder wrote. “Russia is the country where fascism is not only resurgent but even waging a “fascist war of extermination…” “The similarity between what happened then and what Putin is doing is striking.”

Russian political scientist Grigoriо Golosov, head of the political science department at the European University in Saint Petersburg, considers Snyder’s thesis (on Facebook) unscientific. The scientific thing to do, Golosov argues, is to work out the similarities and differences. Golosov prefers the term “personalized dictatorship” for Putin’s regime—a trivialization of Putinism. Putinism is not simply an authoritarian regime, but a fascist quasi-ideology drummed into the population at enormous propagandistic expense. It is driven by the imperialist impulses of Putin, who is waging a war of aggression to realize his expansionist fantasies. The partial analogy to “Hitlerism” is evident.

It does not matter whether the classification of Putinism as fascism or as Nazism is scientific or not. As long as Putin wages war in Ukraine, it is a matter of public impact of this term. After the war, historians and political scientists may take care of its scientific classification.

Comparisons between Putin’s Russia and Hitler’s Germany are means of propaganda defense, as the Russian sociologist Grigoriy Yudin states. He teaches at the Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences (MSSES). After taking part in a protest against the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, he was beaten unconscious by police. Historical analogies reveal historical continuities. (“new people make old experiences”). “The most obvious analogy to today are the years 1938 and 1939, Grigory Yudin explained in an interview with Meduza at the beginning of March 2022.

American historian Anne Applebaum underscores the point: “The attempt to erase the Ukrainians, to eliminate Ukraine from the map, to commit genocide in Ukraine, all of this is fascist. It should remind us of Hitler’s Germany.”

The comparison of Putin with Hitler takes on grotesque proportions in Russia’s disinformation narrative that Ukraine is ruled by a fascist junta, that came to power through an armed coup from which Ukraine must be liberated through war. At the head of the junta is a Jewish Nazi named Zelenskyy, whom Ukrainians elected as president in May 2019 with 73% of the vote in free and fair elections.

Russia’s paradox that a Jew presides over a Nazi junta in Ukraine further fuels its claim that the Ukrainian state does not exist in reality.

In Germany, there is a certain inhibition to regard today’s Russia, Putin’s Russia, as fascist. In public discourse, and not only in the “left camp,” the admissibility of equating Putinism and “fascism” is questioned.

The Soviet Union presented itself as “anti-fascist.” Yet its Stalinist system of terror even surpassed the fascist repression in Germany. Soviet anti-fascism was by no means the opposite of fascism, “for fascist politics begins,” as the (NS-affine) Carl Schmitt said, “with the definition of the enemy. And Soviet anti-fascism meant only the search for an enemy,” Snyder explains.

Putinism is fascism. It is one of the many variants of the Italian original that were politically en-vogue in the 1920s and 1930s. Other examples include:

- The British Union of Fascists of Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, who lived from 1896 to 1980.

- The ultra-nationalist, anti-Semitic, and monarchist “Action française” of Charles Maurras, the hotbed of various French fascist variants.

- The manifold racist fascisms rooted in American history, survive to this day in the contemporary variety of “Trumpism.”

In his 1991 book “The Nature of Fascism,” the British humanities scholar Roger Griffin distilled fascism’s nature from the synthesis of historical, political, social, and psychological ideas. The driving force of fascism, according to Griffin, is the utopian myth, the “core myth,” of a reborn national community.

The Oxford Brookes University professor of modern history considers the synthesis of palingenesis and ultranationalism, “palingenetic ultranationalism,” as the core or “the fascist minimum” of generic fascism, which distinguishes it from para-fascisms and other authoritarian nationalist ideologies.

Griffin revealed the structural affinity between fascism and National Socialism and the other fascist movements of the interwar period. What is typically ignored is the aspect that fascism and National Socialism were defensive movements against the atheistic specter of communism that had been circulating in Europe since 1848— the Communist Manifesto, for example. Fascism and National Socialism attracted bourgeois and Christian support. By the 1920s, Bolshevik communism had long ceased to be a specter and had become a real monster.

One serious difference between National Socialism and most historical fascisms seems to be that Putinism is not anti-Semitic, which is why Israel can maintain pragmatic relations with Putin’s Russia—and Putin thinks he can call his opponents, especially Ukrainians, “anti-Semitic.”

Is Putin’s Russia really fascist?

The American historian and political scientist Alexander Motyl, a Rutgers University professor who specializes in Ukraine and Russia, asked in 2007: “Is Putin’s Russia fascist? – a rhetorical question that he himself answered in the affirmative.

“All the post-Communist states of the former Soviet empire have experienced significant change in the last twenty years, but […] Russia passed from totalitarianism to several years of both authoritarianism and democracy – only to abandon democracy completely and embark on a transition to what is arguably fascism. […] Vladimir Putin’s Russia has enough of the defining characteristics of fascism to qualify as fascistoid – that is, as moving towards fascism,” Motyl wrote in National Interest magazine.

A fascist system has established itself in Russia, Motyl stated in his article published in 2009 in the journal OSTEUROPA entitled (one) “people,” (one) “state” (one) “leader”: Its characteristics are hypernationalism, state fetishism and the cult of masculinity around Vladimir Putin,” according to Motyl.

Vladimir Putin’s Russia has enough of the defining characteristics of fascism to qualify as fascistoid – that is, as moving towards fascism.

Alexander Motyl, 2007

The historian Leonid Luks in a replica, also published in 2009 in the journal OSTEUROPA, considered Motyl’s thesis that Russia was a fascist state or at least on its way to becoming one untenable. Central characteristics of German and Italian fascism, such as a comprehensive ideology or the glorification of violence, are foreign to the “bureaucratic authoritarian regime” that has been established under Putin. Those who subsume the Putin regime under the term “fascism” run the risk of misjudging the threat posed by “real” Russian fascism.

The American historian Marlene Laruelle, director of the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies at The George Washington University, also argues in her profound analysis of fascism, “Is Russia Fascist?” from 2021, that the accusation of fascism against the Putin regime is a “strategic narrative of the current world order/”In other words, framing propaganda.

The classification of today’s Russia as fascist was contradicted by scientific arguments in 2016 by the German political scientists Steffen Kailitz of the Hannah Arendt Institute for Research on Totalitarianism in Dresden, Germany, and Andreas Umland, who in 2016 held the chair of political science at the National University Kyiv Mohyla Academy. According to their analysis of fascism, Putin’s Russia, for all its authoritarian attributes, cannot be classified as fascist or even fascistoid or proto-fascist.

Kailitz and Umland investigated the question of when an “electoral autocracy” runs the risk of being overlaid by a fascist ideocracy. They did see fascists and nationalists at home in Russia at the time. But unlike interwar Germany, they had no chance to use elections or penetrate civil society to gain political support. The continued presence of Putin, an authoritarian but not fascist national leader, prevented Russia from becoming a liberal democracy. Yet, at the same time made it unlikely “for now” that his regime would turn into a fascist one. The same factors that facilitated the establishment of an autocratic system by the “charismatic authoritarian actor” Putin kept Russia from becoming a fascist ideocracy. “Unless a major upheaval occurs, Russia will remain an electoral autocracy for a long time,” the authors wrote in 2016.

This upheaval, a “turn of the times,” as German Chancellor Olaf Scholz aptly named it occurred with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. This could mean, taking the argument of Kailitz and Umland further. Russia is now open to a fascist “March on Moscow,” a storming of the Kremlin—unless there is a self-transformation of Putin’s personal dictatorship into a genuinely fascist system.

Kailitz and Umland emphasize that actors and their ideologies “matter a lot,” which does not mean that socio-economic and institutional conditions are irrelevant. But in times of crisis, institutional structures become “malleable,” and the scope for the main actors is broader than in normal times. When actors play a critical role, the outcome—here the answer to the question: “Where is Russia heading?”—is difficult to predict. To answer this question, they say, one must not only follow polls and public discourse, but study the behavior, composition, and attitudes of Putin’s entourage.

In fact, Putin’s Russia is not a totalitarian, not even a populist “ideocracy” in which citizens follow an ideology more or less voluntarily, but rather an “electoral autocracy.” Putin’s state is not governed according to the ideological principles of fascism. In his eclectic worldview, the authoritarian ruler in the Moscow Kremlin combines Russia’s historical autocratic and expansionist traditions with the claim to be the “protecting power” of all Russophone minorities abroad—i.e., the ”Russkiy Mir” or Russian World. He furthermore instrumentalizes the traditional symphony of the Russian state and the Russian Orthodox Church with the traditional moral values held high by the latter as well as with a hypertrophic nationalism. This vague ideology is the superstructure of the autocratic, Karl-Marx basis of his regime. The practices of rule generally described as “fascist,” such as the repression of all opposition by violent police and secret service in the tradition of the KGB or FSB, total state control of the media, pervasive and hysterical propaganda, and the massive falsification of elections by means of political technologies characterize Putin’s regime. What is missing are genuine mass organizations to mobilize the population. The party of power, “United Russia” or “Edinaja Rossija,” is not a mass party.

The ideological “superstructure” of Putinism

After the end of the Soviet Union, the Russians experienced that democracy resulted in the dissolution of the state, states Rainer Goldt, professor of Slavic studies at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany. The Russian philosopher Ivan Ilyin, who lived in exile in Germany, had this experience during the Weimar Republic. His writings on this subject were rediscovered in Russia after 1991.

The political upstart Putin must have particularly liked—secretly, of course— the infamous essay that Ilyin wrote after Hitler’s seizure of power, Goldt speculates. In it, he praised the German people for having legitimately freed themselves from the “shackles of democracy.”

This real experience of state collapse combined with imperial nostalgia and reinforced by other contemporary historical events such as the war in Yugoslavia, which must have seemed like a portent to Putin, indicating the disintegration of the Russian Federation – is ideologically “built over,” in the sense of Karl Marx by the ideas of Russian and German philosophers of religion and law. They praised Italian fascism and German National Socialism and admired their leaders, the “Duce” Benito Mussolini and the “Führer” Adolf Hitler. They have produced an aggressive mixture in Putin’s mind that ripened into the will to go to war in Ukraine.

Philosophical and political theories since the mid-19th century formed both Hitler’s and Putin’s ideological foundations. From 2007 onwards, the “philosophical underpinning” in Putin’s speeches increased, especially with the ideas of Ivan Ilyin,” the “most radical mastermind of Russian neo-imperialism” in the 20th century, Goldt states.

Historical and contemporary thought leaders who created the contemporary Russian ideology

Ivan Ilyin

The Russian philosopher Ivan Ilyin was an aristocratic monarchist and militant anti-Bolshevik. He died in exile in Switzerland in 1955.

The Orthodox religious philosopher owes his intellectual resurrection to Russian President Putin. Timothy Snyder sees him as the “prophet of our age.”

After World War II, Ivan Ilyin published fascist pamphlets under the title “Our Tasks..” Fascism is “a redemptive excess of patriotic despotism,” says Putin’s ideological foster father. Pure arbitrariness is also at the core of Russia’s war against Ukraine, says Snyder

The Russian philosopher Ivan Ilyin claimed what Putin repeatedly says in his speeches and essays, that Ukraine, in its drive for independence, was only being abused by hostile powers to harm Russia.

Ilyin viewed Ukraine, whose culture he disdained, with great reservation. Ilyin also claimed what Putin repeatedly says in his speeches and essays, that Ukraine, in its drive for independence, was only being abused by hostile powers to harm Russia.

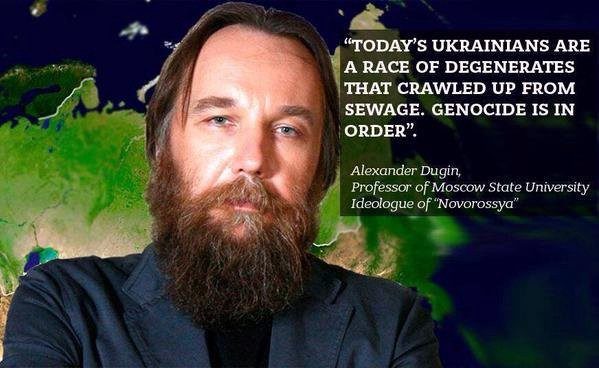

Aleksandr Dugin

The national Bolshevik neo-Eurasian Aleksandr Dugin is regarded abroad as Putin’s house ideologue.; But Putin’s project of a “Eurasian Union” on the economic basis of the Eurasian Economic Union, which has been in force since 1 January 2015, is not a reflection of Dugin’s “Neo-Eurasianism.”

The USA continued to be demonised by Dugin and described as a “new Carthage” that had to be destroyed. Russia, on the other hand, was defined by Dugin as a place where the “new geopolitical gospel” was emerging, namely the “Eurasian idea” predestined to redeem all humanity from “globalism.”

Unlike other political observers, Rainer Goldt does not consider Dugin’s influence on Putin’s politics to be very great. His “Neo-Eurasianism” is more likely to find favor in Russia’s political class, namely with Sergei Karaganov, in military circles, and – in the intellectual Russian “New Right” abroad.

According to Leonid Luks, Dugin initially had high hopes for the Putin government. However, Putin’s glorified image began to crack after the terrorist acts of 11 September 2001 in the United States. Dugin considered Putin’s entry into the anti-terror alliance dominated by the United States a fatal mistake. America continued to be demonized by Dugin and described as a “new Carthage” ± that had to be destroyed. Russia, on the other hand, was defined by Dugin as a place where the “new geopolitical gospel” was emerging, namely the “Eurasian idea” predestined to redeem all humanity from “globalism.”

Immediately after the recapture of the Ukrainian oblast capital Kherson by Ukrainian forces in mid-November 2022, Dugin spectacularly distanced himself from Putin. In a letter circulating on the internet, Dugin emphasized that it was not the Russian generals but “the autocrat ruling in Moscow” (Putin) who was solely to blame for this defeat. Not least for this reason, Dugin pleaded, albeit indirectly, for Putin’s removal from power

In his 1997 book “The Foundations of Geopolitics; The geopolitical future of Russia,”, Alexandr Dugin, following the British geographer Sir Halford John Mackinder and the German geographer Karl Haushofer described approaches for pushing back the influence of the United States and restoring Russia’s world power. Some considered Haushofer as the ideological teacher of Hitler and the spiritual father of Nazi ideology. Dugin’s work is used as a textbook at the Military Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.

This book may have actually influenced Putin’s foreign policy and eventually led to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In this book, Dugin calls on Russia to take a last stand against the victors of the Cold War. Russia’s revenge, however, only has a chance of success if it succeeds in restoring its former hegemonic position in Europe and Asia.

For Dugin, unlike many other imperial nostalgics in Russia who seek the restoration of the balance between East and West, the restoration of the former borders of the Russian empire is only the first stage of his strategic plan. The real goal of the restored empire is the struggle for world domination, the “final struggle.” “The new empire is to be Eurasian, continental, and in a wider perspective: “The Russians’ struggle for world domination is not yet over.”

In 2021, after NATO’s debacle in Afghanistan, Aleksandr Dugin published a manifesto entitled “The Great Awakening against the Great Reset.”. In it, he fantasizes about an “anti-globalist” coalition, led by Russia, of countries supposedly suffering under the “yoke of the globalists”, such as China and India, (Shiite) Iran and (Sunni) Türkiye, African and South American states and even movements like the “Trumpists” in the United States Dugin predicts a battle against “humanity” sparked by “liberalism.” In early January 2023, Dugin wrote that the war in Ukraine was a battle between heaven and hell. Russia was fighting there against the “satanic West.”

This preference for final battle scenarios, for a kind of “twilight of the gods,” reflects the unprecedented cultural pessimism of many Russian critics of the West. Leonid Luks states that a “doomsday mood” like that which prevailed in the national camp, namely among the thinkers of the “conservative revolution,” admired by Dugin, such as Leonid Luks, in Germany after the First World War. “Thus Dugin and his comrades-in-arms clearly tie in with the Weimar Right with their almost hysterical end-time sentiment,” according to Luks.

It is to be hoped that Putin, who has the nuclear potential to destroy the world, does not share this “doomsday mood.”

This preference for final battle scenarios, for a kind of “twilight of the gods,” reflects the unprecedented cultural pessimism of many Russian critics of the West

Lev Gumilev

While Dugin spreads his ideas mainly on social media, the ideas of the unorthodox Lev Gumilev, a Soviet historian, ethnologist, and anthropologist who lived from 1912 to 1992, permeate the academic space.

Gumilev, who took up the ideas of the “Eurasianists” and who became a cult figure after his death, had probably little influence on Putin. Putin pursues Russian imperial goals in the “turn to the East.”

Gumilev’s behaviorist theory of ethnogenesis, which he derived from the history of Eurasian nomads, hardly interests Putin, even if Gumilev’s idea of an intense flowering of the ethnos, e.g., “passionamost’,” and “passionarity” inspired by an innovative leader might appeal to him.

In a speech in Astana, Kazakhstan, where Gumilev is revered for the importance he gives to Eurasian nomads, Putin opportunistically remarked that Gumilev’s ideas would conquer the masses. In his account of Russian history, Gumilev emphasized the difference between Kyivan Rus and Muscovite Russia and stressed the role of the Mongols in the formation of the Russian ethnos. His views are marked by a strong anti-Western resentment.

Theorists like Gumilev and Dugin were partly responsible for Russia’s turning away from Europe, writes Andreas Umland. Post-Soviet public discourse is infected with speculative, often conspiratorial, and sometimes occultist or racist theories. According to Kailitz and Umland, “para-academic” tendencies in Russian social science and an “intellectual deformation” of the Russian elite by the Manichean ideas of Dugin and Gumilev helped prepare the war against Ukraine.

While Dugin spreads his ideas mainly on social media, the ideas of the unorthodox Lev Gumilev, a Soviet historian, ethnologist, and anthropologist who lived from 1912 to 1992, permeate the academic space. Gumilev, who took up the ideas of the “Eurasianists” and who became a cult figure after his death, had probably little influence on Putin. Putin pursues Russian imperial goals in the “turn to the East.”

Gumilev’s behaviorist theory of ethnogenesis, which he derived from the history of Eurasian nomads, hardly interests Putin, even if Gumilev’s idea of an intense flowering of the ethnos, e.g., “passionamost’,” and “passionarity” inspired by an innovative leader might appeal to him. In a speech in Astana, Kazakhstan, where Gumilev is revered for the importance he gives to Eurasian nomads, Putin opportunistically remarked that Gumilev’s ideas would conquer the masses. In his account of Russian history, Gumilev emphasized the difference between Kyivan Rus and Muscovite Russia and stressed the role of the Mongols in the formation of the Russian ethnos. His views are marked by a strong anti-Western resentment.

Theorists like Gumilev and Dugin were partly responsible for Russia’s turning away from Europe, writes Andreas Umland. Post-Soviet public discourse is infected with speculative, often conspiratorial, and sometimes occultist or racist theories. According to Kailitz and Umland, “para-academic” tendencies in Russian social science and an “intellectual deformation” of the Russian elite by the Manichean ideas of Dugin and Gumilev helped prepare the war against Ukraine.

Anatoly Fomenko

Anatoly Fomenko is a mathematician at Lomonosov University in Moscow, a conspiracy narrator, and an author of a total revision of history.

According to Fomenko, the European continent was originally colonized and dominated by Russians. Putin does not refer to Fomenko’s absurd “New Chronology” in his speeches. Still, it is taken up by politicians in his environment, such as Sergei Glaz’ev, one of his advisors: In September 2020, he proposed in an article to use Fomenko’s “New Chronology” as the basis for a new historiography.

Fomenko reveals a great conspiracy of “The West”: He claims that in the 16th century Western chroniclers falsified history and extended it by 1000 years in order to diminish Russia’s importance.

In his “New Chronology,” in which Crimea is the birthplace of Christ, Fomenko reveals a great conspiracy of “The West”: He claims that in the 16th century, Western chroniclers falsified history and extended it by 1,000 years to diminish Russia’s importance.

Sergey Karaganov

The Mephistophelian whisperer Sergey Karaganov, Honorary Chairman of the Russian “Council for Foreign and Security Policy,” and historian and scientific director of the faculty of world economy and world politics of the National Research University, has for years held the interpretive authority over the impact on Russia of global shifts in the political and economic balance of power and influenced the formulation of the Kremlin’s reactionary geopolitics.

Karaganov conceived the disastrous strategies for Russia’s foreign and security policy. He is considered the inventor of the concept of Russia as the protective power of Russians living abroad, i.e., the” Karaganov Doctrine.” Karaganov propagates Russia’s “turn to the East”. It was probably Karaganov who provided the ideas for the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine.

Karaganov is considered the inventor of the concept of Russia as the protective power of Russians living abroad. He no longer speaks of “zones of influence” but of a “global majority” fighting against the “collective West.”

He himself does not know how the war will end; a solution would involve the division of Ukraine. “Hopefully, in the end, there will be something left called Ukraine,” Karaganov feigned in the interview.

Karaganov seems to have retained some residual sense of reality when he recognizes China as the “clear winner” in this whole “affair.” The Europeans, of course, are the “biggest losers.” While Karaganov doubts that Russia could become a “satellite state of China,” he expressed “concern” about China’s overwhelming economic dominance in the next decade. That’s why “people like me” had said, “We have to solve the Ukraine problem, we have to solve the NATO problem, so we can have a strong position vis-à-vis China.”

In the September / October 2022 issue of the Russian-English foreign policy journal and platform, “Russia in Global Affairs,” Karaganov wrote in an article: “The conflict between Russia and the West has turned into a direct confrontation, a hybrid war. It will last a long time – regardless of the situation on the Ukrainian front.” (Karaganov suspects the war with the West will last for 15 years. Ukraine is not even the main arena of this confrontation, Karaganov admits.

With regard to the solution to the “Ukrainian question,” much depends on the outcome of the “СVО,” the “Special Military Operation.” The “denazification” or “eradication of aggressive nationalism” is only possible with a “complete occupation of the territory of today’s Ukraine,” and “by means of political cleansing.” For this, Russia must prepare for a long-lasting military operation, “always on the brink of an escalation and confrontation with the West, up to and including a limited nuclear war.” Without this threat, the West would hardly be willing to negotiate.

As a metaphor for the upcoming period, Karaganov invented the term “Fortress Russia” But “without isolation,” i.e., without Vladislav Surkov’s “One Hundred Years of Geopolitical Solitude.” “We are the civilization of civilizations, according to Karaganov. “We are for the right of everyone to live according to his principles and traditions—“Ukrainians excepted”—against any hegemony or any claim to truth in the last instance.” The struggle against the expansion of the West, which today is focused on Ukraine, is a struggle for a new just world order. The West, especially the United States, is not only pursuing a policy of containment of Russia but of the destruction of the Russian state. And this “war for survival” had been forced on Russia. The West’s hostility towards Russia was caused by Russia’s refusal to play by the old rules, i.e., to abide by international law. The motives were, according to Karaganov, primarily within the Western world: The West needed Russia as an enemy to unite against.

Putin’s war against Ukraine is also a war against the international order established after World War II, against the UN Charter of 1945, which contains an absolute prohibition of war of aggression, and against the European order established after the end of the Cold War in the “Charter of Paris for a New Europe” on 21 November 1990. For the German political scientist Herfried Münkler it is clear that Putin is “striving for a large-scale revision of the European order.” It is this motive that drives Putin above all others, according to Münkler

The “denazification” is only possible with a “complete occupation of the territory of today’s Ukraine” and “by means of political cleansing”

Sergey Karaganov, Honorary Chairman of the Russian “Council for Foreign and Security Policy”

Carl Schmitt

The ideas of National Socialist German constitutional lawyer, Carl Schmitt, prominent in the 1930s and 1940s, are experiencing a renaissance in Putin’s Russia. Russia’s war against Ukraine is a return to the “law of the strongest,” legally exaggerated in Carl Schmitt’s concept of sovereignty. “Sovereign is who decides on the state of emergency,” according to Schmitt.

Many Russian political scientists think that one has to read Schmitt to understand Putin’s politics, says Russian journalist Maxim Trudolyubov Putin’s “entire power is based on the state of emergency.” The “sovereign state” does not need to abide by any rules.

Alexander Dugin also refers to Schmitt’s “concept of the political,” for whom the distinction between friend and foe was the most essential criterion of politics. Dugin regards as enemies “the new world order, the open society, liberal world government, the global market, the one-world model and Western universalism.”

Putin’s “entire power is based on the state of emergency.”

Maxim Trudolyubov

Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Joseph Arthur de Gobineau

Hitler probably absorbed the writings of the most prominent representatives of the pseudo-scientific racial doctrine. One was English-German “Wagnerian” Houston Stewart Chamberlain. He promoted social Darwinism in Germany. The other was the French diplomat and writer Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, who became famous for his ” Essay on the inequality of human races.”.

Putin has certainly not read these two masterminds of genocidal racism. Putin is not a racist, and clearly differs from Hitler on this point.

“Russkiy Mir” – the “Russian World”

“Russkiy Mir” is originally a cultural concept postulating the togetherness of Russian-speaking, East Slavic, and Orthodox-religious people. It has replaced the narrower idea of “Orthodox Civilization” in current Russian discourse.

Putin uses the concept to legitimize Russian influence in the post-Soviet space. He defined the concept programmatically at a meeting of cultural leaders in 2006 as follows: “The ‘Russian world’ can and must unite all those who hold the Russian word and Russian culture dear, wherever they live, in Russia or outside it. Use this expression as often as possible.” He officially declared 2007 the “Year of the Russian Language.”

The cultural project became a political ideology used to justify Russia’s 2008 intervention in Georgia, the 2014 annexation of Crimea and military intervention in the Donbas since 2014, and the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Parallel to the political instrumentalization of the cultural project, an institutionalization of the “Russian World” took place. A state foundation named “Russkiy Mir” has existed since 2007. Its declared aim is to “promote the dissemination of ‘objective’ information about Russia, about Russian compatriots abroad, and the creation of a world public opinion sympathetic to Russia.”

The chairman of the foundation is the political scientist Vyacheslav Nikonov, grandson of Stalin’s Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov. The Foundation’s advisory board includes the minister of education, the minister of culture, and the minister of foreign affairs of the Russian Federation.

The Russian Orthodox Church – Putin’s spiritual army

The Byzantine doctrine of “simfonija,” or harmony, is again shaping the relationship between state and church in Putin’s Russia. The separation of church and state no longer applies in Russia. Putin’s state and the church of Patriarch Kirill instrumentalize each other.

Kirill sees Russia in a metaphysical struggle against Western liberalism and justifies the war of aggression against Ukraine which has “not a physical but a metaphysical meaning.” He grants the remission of punishments for sins for the Russians killed in battle

Putin’s Russia has once again turned into an “Empire of Evil,” as former US President Ronald Reagan put it. The clergy of the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church incites the faithful to unchristian hatred of Ukraine. Patriarch Kirill is, so to speak, the high priest of evil, the “Antichrist”—to abide by Christian terminology.

Kirill sees Russia in a metaphysical defensive struggle against Western liberalism and individualism. He justifies the war of aggression against Ukraine, an outpost of the West, which has “not a physical but a metaphysical meaning.”

He declares the young Russian soldiers who kill Ukrainians to be “heroes,” supports the mobilization, and grants an “indulgence,” which the Orthodox Church does not even recognize, the remission of temporal punishments for sins for the Russian soldiers killed in battle, indeed the forgiveness of “all sins,” which puts him close to jihadist preachers of hate.

Vladimir Putin and Patriarch Kirill. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The “Ukrainian Orthodox Church / Moscow Patriarchate” is part of the “Russian Orthodox Church” in Ukraine. Its clergy acts as Moscow’s “spiritual fifth column” in Ukraine.

Hitler’s Germany – Putin’s Russia: “Revisionist Powers”

The “Stab in the Back” Legend (“Dolchstoßlegende”) – Betrayal on the Home Front

The “Stab in the Back” legend did not experience a new edition after the German defeat in the Second World War. A myth like the “betrayal on the home front” in 1918 did not exist in 1945. After the defeat of the German army, “undefeated in the field,” in the First World War, the feeling of the “aggrieved nation” dominated the national-minded part of the German people. Nor was there any question of war guilt after 1945. “It was too obvious that the man at the head of the ‘Third Reich’ had unleashed the Second World War and bore the main responsibility for its results,” wrote Heinrich August Winkler. That is why the Federal Republic, unlike the Weimar Republic, was able to develop without the ballast of the myths that had helped to destroy the first German democracy at the time.

Russia’s “Versailles Syndrome”

Rüdiger von Fritsch, German ambassador to Moscow from 2014 to 2019, notes a “Versailles syndrome” and an “imperial reflex” in Russia. The “simple Russians” need the “old greatness of the empire” to compensate for their “meager existence.” And the return of Ukraine to the rule of the Moscow Kremlin is, for them, the criterion for this “greatness.” The self-aggrandizement resulting from the humiliation by others, the conceit of uniqueness and specialness, is a psychological phenomenon that is only too well known from German history.

The “simple Russians” need the “old greatness of the empire” to compensate for their “meagre existence.” And the return of Ukraine to the rule of the Moscow Kremlin is for them the criterion for this “greatness.”

Rüdiger von Fritsch, German ambassador to Moscow (2014-2019)

In Russia, the myth of the mysterious “Russian soul” corresponds to the “German essence,” the cultural arrogance in Germany. It was insulted by the West, says the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Svetlana Alexievich of Belarus. It is now taking revenge on Ukraine with a murderous war as a proxy for the United States and the European Union.

Putin is a revisionist like Hitler, who was dominated by the “Versailles complex” of the Germans after 1918. Putin is dominated by a “Russian Versailles complex” due to the “defeat” of the Soviet Union in the Cold War. The revision of these defeats is a driving force of both dictators.

A revisionist tone in Putin’s rhetoric was already audible in the 1990s, long before he became president of the Russian Federation. The much-quoted phrase about the disintegration of the Soviet Union as the “greatest catastrophe of the 20th century”—not World War I, not World War II with its 25 million dead Soviet soldiers and civilians, certainly not the “Shoah”—was uttered as early as 1994.

At a Körber Foundation conference in St. Petersburg on “Russia and the West” in March 1994, the yet unknown Deputy Mayor Vladimir Putin spoke up with this phrase. The reasoning that follows in his next sentence is rarely quoted: For Putin, the fact that as a result of the independence of the Union republics (Ukraine, Baltic States, Central Asia, South Caucasus), “millions of Russians live outside the Russian state” was the greatest catastrophe – betraying his “völkisch,” ethno-nationalist thinking.

For his appearance before the German Bundestag on 25 September 2001, which was accommodating to the West, Putin received a standing ovation from MPs of all parties longing for reconciliation with the “East.” They turned a blind eye to the second Chechen war that had just ended, which the KGB officer Putin had started with a false flag operation. He fabricated an alleged Chechen attack on an apartment building in Moscow—very much in the style of Hitler’s alleged Polish attack on the Gleiwitz radio station—and waged with extreme brutality. In retrospect, it is clear that the “other” Putin deceived the world about his true intentions with his speech at the time.

In his aggressive speech at the 43rd Munich Security Conference on 9 February 2007, with which he startled the Europeans, Putin had already half-opened his visor. It was a barely concealed challenge of the victor in the Cold War. He accused the United States, not entirely unjustified, of striving to become the sole world power

The Russian Federation under Putin has been pursuing an openly revisionist policy since the 2008 Russian-Georgian “Five-Day War,” leading via the annexation of Crimea and the de facto occupation of part of the Donbas to the open war of aggression against Ukraine on 22 February 2022.

Cult of victimhood – instrumentalization of defeat

“The political instrumentalization of (real or perceived) defeat and the self-stylization as a victim of powerful enemies: that is what connects these so different political leaders (Putin and Hitler),” states the German historian Heinrich August Winkler.

In shameless self-pity, on 18 January 2023, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov compared the Russians to the Jews—and the West’s support for Ukraine to Hitler’s “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” The United States had formed a coalition of European states to solve the “Russian question” in the same way Hitler had organized the “Jewish question.”

Putin has built a “historical myth of Russia’s innocence” as a victim of “Hitler’s fascism,” explained Timothy Snyder. Russia portrays itself as the world’s preeminent antifascist power because of its sacrifices in the Second World War, stated Marlene Laruelle.

But Russia is not “innocent” because of its past, as a victim of the German war of aggression. In reality, “Russia” is highly guilty not only because of Stalin’s murderous terrorist system against its own population but also because, as the leader of Bolshevik Russia, Stalin was responsible with national-socialist Germany’s “Führer” Adolf Hitler for World War IIStalin concluded a pact with Hitler, which kept the German aggressor’s back free in the East for his military ventures in the West. And both aggressors invaded Poland together.

The “Aggrieved Great Power” – Russia’s “Weimar Syndrome”

The collapse of the Russian Empire, in its Soviet form, in the 1990s, perceived by most Russians as a defeat in the Cold War, gave rise in Russia to a state of mind similar to the German national state of mind after defeat in the First World War. As in Germany, “post-traumatic collective psychopathologies in Russia created an explosive cocktail of bitterness, conspiracy stories, and palingenetic dreams,” Soviet and American historian Alexander Yano states. This is one of the reasons why the term “Weimar syndrome” has been applied to Russia since the 1990s.

The collapse of the Russian Empire (in its Soviet form) in the 1990s, perceived by most Russians as a defeat in the Cold War, gave rise to a state of mind similar to the German national state of mind after defeat in the WWI.

Parallels between post-Soviet Russia and the Weimar Republic have been part of the constant repertoire of Russian and Western journalism since the beginning of the 1990s, states historian Leonid Luks – what has found its expression in the term “Weimar Russia.” As in the Weimar Republic, democracy in post-communist Russia is associated with the collapse of the country’s hegemonic position on the European continent, with the loss of territories, and with the emergence of a new diaspora.

Stephen E. Hanson, Lettie Pate Evans, Professor in the department of government at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, and Jeffrey S. Kopstein, professor of political science at the University of California, Irvine, however, in 1997, half a decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union, miss a systematic and comprehensive comparison in the articles by countless observers who state an analogy between the Weimar Republic and post-Soviet Russia.

Dealing with revisionist powers

According to German political scientist Herfried Münkler, “revisionist powers” are the greatest challenge to any peace order. They must be weakened so that they are incapable of a factual revision. After its total defeat in 1945, Germany was incapable of revising the results of World War II.

Münkler names three methods in dealing with revisionist powers:

1. “Buying off revisionist desires by transferring wealth”

Germany was pacified, and democratized, in this way. Russia had not suffered a military defeat in 1991; its Soviet empire collapsed. In Russia’s case, the attempt by Germany and the European Union to “compensate” Russia through material prosperity did not work: The memory of former greatness did not fade – and Putin is systematically cultivating it.

2. “Appeasement through political accommodation”

The Western “appeasement policy” has not worked in Russia’s case either. There has been no shortage of appeasement attempts and visits. German Chancellor Merkel, French President Macron, and even United Nations Secretary-General Guterres all visited Moscow to dissuade Putin from an invasion of Ukraine.

3. The third option remains military “deterrence through the build-up of superior military capabilities and the unquestionable readiness to use the.” Russia must be defeated militarily in Ukraine, i.e., weakened militarily to such an extent that it can no longer continue the war. However, an attempt to inflict a military defeat on Russia on Russian soil is impermissible because of the danger of nuclear escalation.

Russia must be defeated militarily in Ukraine, i.e. weakened militarily to such an extent that it is no longer capable of continuing the war. However, because of the danger of nuclear escalation, an attempt to inflict a military defeat on Russia on Russian soil is impermissible.

Ethnic nationalism and multinational reality

There is tension between Russian ethnic nationalism and Russian multiethnic imperialism. The Russian Empire and the Soviet Union were multiethnic empires—and even after the release of the other Soviet republics into state independence, the Russian Federation is still “multinational”, or more precisely: polyethnic. The imperialist claim is supported by a hypertrophic Russian nationalism, but needs the other ethnic groups in the (pseudo)federation to be an “empire.”

Unlike historical fascisms, which aimed for an ethnically homogeneous state, Russian fascism takes reality into account and includes in the “Russian” state the other ethnic groups resident in the Russian Federation, who, in addition, identify with religions other than Russian Orthodoxy. Putin declares that Islam, meaning the Tatars, who form both an ethnic and a religious minority, “belongs to Russia.” Even the Orthodox Russian nationalist Ilyin was of the opinion that everyone should pray in his own way.

“Politics of History” – Hitler and Putin: teacher and pupil

“As a partisan of history politics, Putin comes across as a teachable pupil of Adolf Hitler,” the German historian Heinrich August Winkler states. “Putin thinks in the same categories as Carl Schmitt, the most prominent expert on constitutional and international law of the German interwar period.”

Winkler states: “Two weeks after the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, on 1 April 1939, Schmitt gave a lecture in Kiel with the significant title: “International Law of Greater Spatial Order with a Prohibition of Intervention by Powers from Outside the Territory.”

Schmitt justified Germany’s claim to rule over the Czechs with the special rights resulting from the fact that Germany was not an ordinary nation-state, but an “empire” from time immemorial.” On 6 September 1938, at the Reich Party Congress called “Greater Germany” in Nuremberg, Hitler invoked the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation,” to which Bohemia and Moravia had belonged for centuries.

On 28 April 1939, Hitler justified the establishment of the “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” before the Greater German Reichstag by invoking the “Monroe Doctrine” of 1823. The Monroe Doctrine was a US foreign policy maxim articulated by President James Monroe in 1823. It postulated that any intervention by foreign powers in the political affairs of the Americas would be an act hostile to the United States. “Exactly the same doctrine we Germans now advocate for Europe, but in any case for the sphere and concerns of the Greater German Reich,” Hitler said.

Claiming a sphere of influence in which the European Union, the United States, and the United Nations have no business, the Russian president postulates a quasi “Putin Doctrine.”

Like Carl Schmitt and Hitler, Vladimir Putin underpins Russia’s claim to a geopolitical sphere of influence of the historical size of the Russian Empire. In his July 2021 article “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” Putin invoked Volodymyr, the Grand Prince of Kyiv and Prince of Novgorod as the “Mehrer,” A Roman-German imperial title that means “augmenter” of the Russian Empire. By 980, Volodymyr had consolidated the principalities of Kyiv and Novgorod, located in present-day Russia, into one empire extending to the Baltic Sea.

Putin assumes a transfer of the empire of Kyivan Rus – in the sense of a profane “translatio imperii” – to the Russian Empire. In Putin’s understanding of history, there is a thousand-year continuity of “Russian” history with an imperial and autocratic tradition. The current ruler in the Moscow Kremlin claims the Kyiv historical heritage for himself and thus rules over the Ukrainians.

The thesis of the common origin of Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians in medieval Kyivan Rus is not wrong, but the line of common proto-statehood was cut in 1240 by the invasion of the Mongols and Tatars. In the following 250 years of Mongol rule over the northeast Grand Duchy of “Moskovia,” and Polish and Lithuanian rule over the southwest, Kyiv, of medieval “Rus,” Russians and Ukrainians developed apart.

NSDAP and “United Russia” – Movement Party and State Party

One of the differences between “Hitlerism” and Putinism is the character of their popular base.

Unlike the various fascisms of the 1920s and 1930s, “Ruscism” is not a mass movement; such a movement is only simulated by the Kremlin. When asked about it in surveys, the majority of Russians profess their support for Putin and his officially proclaimed policies, including his war of aggression against Ukraine, but are not “moved” by him. The ruling regime party “Yedinaya Rossiya” feigns majority support by the population, which in reality is politically apathetic and resigned and, as in the Soviet Union, obediently votes for the candidates put up by the regime.

Unlike the various fascisms of the 1920s and 1930s, “Ruscism” is not a mass movement; such a movement is only simulated by the Kremlin.

“Classical fascism demands mobilization of the masses. The “NSDAP,” Hitler’s “National Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany,” was a mass movement. So was Mussolini’s “National Fascist Party,” the “Partito Nazionale Fascista.” Putinism does not need a mass movement. It wants complete passivity. Anything that does not come from the state has no right to exist. Real mass movements are not in the Kremlin’s interest, Vladislav Inozemcev explains. Instead, state propaganda relies on conspiracy narratives.

Russia’s “de-putinisation” after the war

Putin named the “de-nazification of Ukraine” as the goal of his “special military operation,”; but it is Russia that needs “de-putinisation” for existential reasons. To free themselves from backward-looking thoughts and feelings and to be able to look forward, the Russians, in whose minds official propaganda has caused a loss of reality, would need something like a compulsion to recognize reality.

A military defeat in Ukraine could bring about such a reality gain. Putin is waging a “final battle against reality,” Maxim Trudolyubov explained. All around him, he said, was only “imitation and façade—a world of lies.”

The Russians, in whose minds official propaganda has caused a loss of reality, would need a compulsion to recognise reality. A military defeat in Ukraine could bring about such a “reality gain.”

“To get out of the historical vicious circle of disaster and humiliation, Russia needs “de-putinisation.” But who is to bring about the process of ideological detoxification and how? For Russia, there is no other way than a long, painful rebirth,” wrote the Russian-Swiss writer Mikhail Shishkin in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung after Putin invaded Ukraine.

The Russians should not be spared the farewell to empire, said Ralf Fücks at the annual conference of the “Deutsche Gesellschaft für Osteuropakunde, “German Society for East European Studies, in Bonn on 17 June 2022. Fücks is managing partner of the NGO Zentrum Liberale Moderne. Russia needs a military defeat to let go of its world power delusion—just as Germany did in 1945. Russia, too, must face up to its history, he said.

“Russia needs a culture of guilt,” says Ukrainian historian and publicist Andrij Portnov. He is a professor of “Entangled History of Ukraine” at the European University Viadrina and director of the PRISMA UKRAЇNA Research Network Eastern Europe in Berlin.

Most Russians “support” Putin’s war against Ukraine out of a perverse “love of Russia.” Their “patriotism” dictates that they approve of the war atrocities committed by Russian soldiers and rejoice over Ukrainian corpses in the streets of bombed-out Ukrainian cities. This morally blind patriotism is reminiscent of the American motto, “My country, right or wrong.”

Whether a military defeat in Ukraine will bring about mental changes in the Russian population, the overcoming of the imperial phantom pain is doubtful. The propaganda would gloss over it. It would probably require a defeat on Russian soil, which, however, Russia does not have to fear because of its arsenal of nuclear weapons and intercontinental carrier rockets.

According to the Latvian Defence Minister Artis Pabriks, it would be “healthy” for Russia to suffer defeat in its war against Ukraine so that it could free itself from its imperialist mentality: “As a former political scientist, I personally think that the Russian people should suffer defeat in this war because it would be healthy for them to lose the war so that they can see the world with different eyes. […] Our only hope is that the people of Russia change their attitude and realize the greatness of their own country instead of trying to expand beyond its borders.”

Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Pawel Jabłoński cited Germany as an example. It had changed after the end of the Second World War, had shed its “imperialist mentality,”and had developed into one of the strongest economies in the world. “They (the Germans) suffered defeat in the war, they were defeated, and that’s why they had to change, […] And that’s why we’re talking about the Russian Empire, which was never defeated. There were many internal struggles that led to changes in leadership, but the country never decided to stop being an empire…”

Former Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves stated,”We cannot lift the sanctions. They (the Russians) must suffer the consequences, just like fascist Germany after the Second World War. […] So that Russia never behaves like an empire again, it must pay for restoring the status quo (ante) and for what it has done in Ukraine […]”.

Asked whether he wished Russia defeat, Russian writer Dmitry Gluchovsky—in exile since March 2022, accused of “denigrating the Russian army” and wanted—replied that he did not wish Russia defeat “in the senseless struggle against the rest of the world,” but “healing, the expulsion of the demons that have taken possession of it, repentance for what it is doing to Ukraine, and reconciliation with itself.”

III. Putin – Hitler’s “revenant”

Mystifying or even demonizing the ruler in the Moscow Kremlin is not helpful in dealing with him. But the image of Putin as a “revenant” of Hitler in a figurative sense is very well suited for a comparison.

The parallels between the two are striking: both policies are similar internally and externally in demagogic rhetoric, and the forms of their rule are similar in many respects. The difference is that Adolf Hitler did not have to secure the loyalty of his “sub-leaders” through material corruption as Putin has to. The shared ideological sentiment made them stick by Hitler almost to the end.

Putin, on the other hand, secures the loyalty of his followers like a feudal lord by granting fiefdoms, i.e., by granting corrupt opportunities for enrichment. Or, more aptly: like a godfather of “Cosa Nostra”, as which Putin’s environment can be described.

The general perception of Putin as a “new Hitler,” not only in Ukraine but also in large parts of the Western world, is vividly expressed in the casual contraction of their names to “Putler” in Ukrainian media.

Vladislav Inozemcev, however, compares Putin to Mussolini rather than to Hitler: Putin is, in fact, today’s Mussolini. And Steffen Kailitz and Andreas Umland considered Putin more like the “equivalent of Hindenburg.”

The parallels between Putin and Hitler are striking with the difference that Hitler did not have to secure the loyalty of his “sub-leaders” through material corruption as Putin has to. Putin secures the loyalty of his followers like a feudal lord by granting fiefdoms.

Racism and Biologism

Hitler’s racism

Racism was at the core of National Socialist ideology. Not medieval religious anti-Semitism, but modern “racist” anti-Semitism motivated Hitler to the “final solution of the Jewish question” in the course of the war of extermination against the Soviet Union. – A racist hubris, “Germanic master race,” to the intended enslavement of the Slavs after the “final victory” in the territories of Eastern Europe occupied by the Wehrmacht also motivated Hitler. Despite the fact that there is no “Slavic race” and that the Slavic languages linguistically belong to the family of Indo-European languages. Arguably, the main difference between Hitler and Putin is that Putin is not an ideological anti-Semite.the main difference between Hitler and Putin is that Putin is not an ideological anti-Semite.

Putin’s “genetic code“

Putin’s worldview is a Russian ethno-nationalist one, even though he explicitly affirms the belonging of ethno-religious minorities to the Russian empire. He also pays homage to a certain, and contradictory, biologism: “Our genetic code is most likely one of our greatest competitive advantages in today’s world,” Putin declared in a consultative video conference with Russian geneticists on issues related to the development of genetic technologies in the Russian Federation.

“We have a different genetic […] code” than the Americans.” On the other hand, Putin draws on the influence of the environment when he says: “…we learned something completely different from our ancestors” (than the Americans), referring to the values of mutual aid and solidarity, “which are the mainstay of our statehood today”—as opposed to “American values” as expressed in Jack London’s “The Law of Life.” Putin’s hypocrisy knows no bounds.

Hitler’s and Putin’s “genocidal language”

“While not every use of genocidal hate speech leads to genocide, all genocides have been preceded by genocidal hate speech. The modern Russian propaganda state turned out to be the ideal vehicle both for carrying out mass murder and for hiding it from the public,” wrote Anne Applebaum.

“The indifference to violence, the amoral nonchalance about mass murder, even the disdain for the lives of Russian soldiers—is familiar to anyone who knows Soviet history.” “I see signs of genocidal rhetoric against Ukrainians,” said Lviv-born British lawyer Philippe Sands in an interview with the Kyiv Post.

The Russians have been prepared for the invasion of Ukraine for many years by Putin-inspired anti-Ukrainian propaganda on state television, according to Anne Applebaum just as Stalin’s propaganda appeased the consciences of the Soviet “activists” who caused the genocidal famine,” Holodomor,” that killed 3.5 to 5 million people in Ukraine in 1932 and 1933 by mercilessly confiscating all grain from peasants.

The propaganda persuaded them that the peasants, or “kulaks,” were vermin that had to be crushed. Similarly, in the era of National Socialism, Germans were mentally prepared for the genocide of the Jews during World War II through official agitation against Jews and violent attacks on Jews, such as the pogrom that occurred on Nov. 9 and 10, 1938.

Today, less violence than in Stalin’s Soviet Union is needed to disinform and pervert the public, because Russian state television—the main source of news for most Russians—is more sophisticated than propaganda via Soviet “people’s radio,” or “black plates” in the canteens. And because the Putinist trolls and influencers are more professional than Stalin’s agitators, Applebaum writes.

Hitler’s anti-Semitic tirades made Germans indifferent to the suffering of the Jews, and the propaganda of the “Jewish subhumans” turned ordinary German men into mass murderers. On Oct. 4, 1943, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, the organizer of Hitler’s planned genocide of the Jews, delivered “Posen Speech” at an SS Gruppenführer meeting in Posen, infamous for the frankness with which Himmler spoke about the systematic murder of the Jews—a “glory” in SS history—and the moral perversion with which he gave credit to his SS henchmen: “To have persevered through this, and to have remained decent …”

Stalin’s “activists” also had no sense of guilt. Lev Kopelev, who, as a young man in an activist brigade, took part in the confiscations of food in Ukrainian villages, confessed that ideological propaganda helped him hide what he was doing even from himself: “We fulfilled a historic duty. We fulfilled our revolutionary duty.”

The Soviet writer and war correspondent Vasily Grossman has a personal say in his novel, “Everything flows,” “Why was my heart frozen at that time? When such terrible things were done, when so much suffering was happening around me? The truth is that I did not think they were human beings: ‘They are simply kulak filth.’”

The continuing stream of blatant lies about Ukraine in Putin’s state provokes not outrage but cynical apathy among the Russian population, Anne Applebaum states. “They’re not human beings; they’re Ukrainian Nazis.” “And so, like the kulaks before them, they (the Ukrainians) can be eliminated with no remorse,” said President Zelenskyy in a conversation with Applebaum in April 2022.

“Fate” and “Providence”

Putin’s destiny

“When I asked Vladimir Putin,” Ukrainian historian Mikhail Dubinyansky quotes the controversial Russian writer and “national socialist” Aleksandr Prokhanov, “what does the Russian project mean to you? Putin had replied, “Russia, that is not a project; that is a destiny.”

The “fate”— [Russ.: “dolya,” part of a task, i.e., the part of a task that falls to someone, here: to “bring back” Russian land[ —has destined the unbelieving orthodox Christian Vladimir Putin (he has not yet adopted the title “vozhd’,” leader) to “make Russia great again” after the defeat in the Cold War, just as “Providence” had chosen the German “Führer” Adolf Hitler in the last century to make Germany a great power again after the lost First World War.

Putin literally said, “And even if it looks like he (Peter I) took something away from the Swedes, in reality, he only took back what belonged to Russia. Apparently, it is also our lot: to take back and strengthen the country. If we accept this as the basis of our existence, we will solve the tasks ahead of us”.

Hitler’s personal theology

Unlike Putin, who makes the Russian Orthodox Church integral to his Putinism, Hitler, according to Rainer Bucher, professor of pastoral theology and pastoral psychology at the University of Graz., saw Christian churches as opposing rival “loyalty centers.” While the atheist KGB agent Putin mimes the Orthodox faithful, the anti-church Adolf Hitler used as an alternative to Christian terms the vague concept of “Providence,” as whose instrument he saw himself. But he also proclaimed his satanic project in the name of an “almighty Creator.”

Hitler was religious in an unconventional sense. His religious rhetoric was not merely calculated, writes Bucher. He believed in himself as the God-sent bringer of salvation, as he already confessed in his programmatic writing “Mein Kampf.” He even justified the murder of the European Jews theologically: “Thus today I believe I am acting in the spirit of the almighty Creator: By resisting the Jew, I fight for the work of the Lord,” wrote Carl Schmidt.

Hitler’s National Socialism is at its core a political, secularised religion, states the German-American political philosopher Eric Voegelin – as is communism. Hitler wanted to win secular “salvation” (“Heil”) during his lifetime, while Soviet communism saw the “bright future” rising on the temporal horizon—both with extreme violence.

Something of communism’s “bright future” seemed to flicker in Putin when he told the participants of the first meeting of the “Russian Children’s and Youth Movement” in a recorded video message, that the changes taking place in Russia and in the whole world would change everything for the better.

But what is actually to be seen on the horizon is not a “bright future,” but a threatening sheet lightening.

Putin’s “true nature”

The Swedish economist Anders Åslund accuses Western politicians of a “fundamental failure” in assessing the “true nature” of Putin. Many still assume that Putin is a rational actor. Understanding Putin correctly is the key to effective Western policy on Russia and Ukraine.

Åslund strips Putin of his professed political ambitions, such as restoring Russia’s greatness, and shows him what he believes Putin really is: an authoritarian kleptocrat who cares nothing for Russia’s national interest and is fixated only on his power and wealth. He hides his self-interest behind a revisionist-nationalist façade, which secures him the support of the nationalistically incited Russian population.

“The only goal of this vulgar, corrupt regime, this autocracy without a plan or ideology, is to hold on to power,” says Russian writer Dmitry Gluchovsky. Putin’s interests have nothing to do with Russia’s interests, states the Moscow-born American historian Yuri Felštinskij.

Rüdiger von Fritsch, German ambassador to Moscow from 2014 to 2019, disagrees: “Looking back from today, it becomes obvious how consistently Putin has pursued his vision of establishing a new Greater Russian Empire since he entered the political arena.”

It is unlikely that Putin is only the “godfather” of a mafia clan and that his revisionist-nationalist policies are only a “façade”, as Åslund suggests. A certain layer of this “façade” is certainly genuine, i.e., corresponds to his convictions. Unlike Hitler, who made his domestic and foreign policy plans public as early as 1925 in his programmatic writing “Mein Kampf,” Putin pursued his vision of the restoration of a Greater Russian Empire single-mindedly but veiled.

With Hitler, everything is clear: his “worldview”—his pseudo-scientific “racism”—was not feigned, as absurd as it may seem today. Racial theory was popular throughout Europe during Hitler’s political apprenticeship years. Hitler was certainly a true believer in the quasi-religious race ideology.

Unlike Hitler, who made no secret of his contempt for democracy, Putin feigns respect for civil liberties: “Russian politics is based on freedom,” declared the Russian dictator, who tramples on freedom in his country. “And everyone should be able to enjoy this right, including the inhabitants of Ukraine. […] Everyone should have the freedom to decide on his own future and that of his children. And we consider it important that this right can be exercised by all peoples living on the territory of today’s Ukraine”. Putin’s mendacity knows no bounds.

“Appeasement” – then and now

The behavior of the “peace powers” then and now also shows parallels: French President Macron’s ongoing telephone diplomacy and German Chancellor Scholz’s constant willingness to talk are useless: They will not persuade Putin “to give in,” in Angela Merkel’s naive diction. Appeasement did not deter Hitler from his intention to unleash a war. After his invasion of Poland, however, none of the appeasement politicians spoke to Hitler again. Whereas Macron and Scholz do not want to break the “thread of conversation with Putin” even after his invasion of Ukraine.

Putin meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron in Moscow on 7 February 2022 (Photo Elysee.fr)

Before and after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the leaders of Germany and France, the European Union and the United States, and even the Secretary-General of the United Nations, António Guterres, pursued a classic appeasement policy towards Putin. They ignored the lesson of recent history – namely that appeasement of a belligerent tyrant only leads to war. No lesson was learned from “Munich 1938.”