Moldova is caught in the middle of a geopolitical tug-of-war between Russia and the West. In this landlocked country of 2.6 million inhabitants, neutral since 1994, Russia is employing hybrid warfare tactics to reinforce its influence. Recent local elections have shown support for the government's pro-EU course, but several pro-Russian parties were banned, having been accused of acting as destabilization tools on the Kremlin's behalf. Wedged between NATO member Romania and war-torn Ukraine, Moldova's vulnerability is accentuated by the presence, since its independence, of a pro-Russian separatist region, Transnistria, in its eastern part.

In February 2023, Maia Sandu, the president of Moldova since 2020, said that Russia was planning to overthrow the government under the guise of seemingly organic protests that would turn violent. The plot was prevented, but the situation was "really dramatic," she said.

President Sandu added that Russia has tried, and will continue, to interfere in Moldovan politics, stressing that Russian-affiliated forces have funneled a massive amount of money into the country ahead of local elections planned on 5 November.

In its bid to exert influence over Moldovan elections, Russia has deployed a range of tactics, such as manipulating energy resources, launching cyberattacks, bomb hoaxes, internet breaches, and issuing direct threats involving Transnistria, a secessionist pro-Russian state in the East of Moldova.

Moldova's Minister of Defense, Anatolie Nosatîi, highlighted in an exclusive interview with Euromaidan Press that “the Russian Federation extensively employs misinformation campaigns and news as primary instruments to foment instability and insecurity among the citizens.”

The Moldovan government is acutely aware of the need to counter pro-Russian disinformation campaigns to maintain political stability and uphold the country's pro-European orientation.

As expressed by Minister Nosatîi, “We are striving to provide the right information to inform the public about the current situation and our activities. Our goal is to prevent the Russians from escalating this situation and creating tension.”

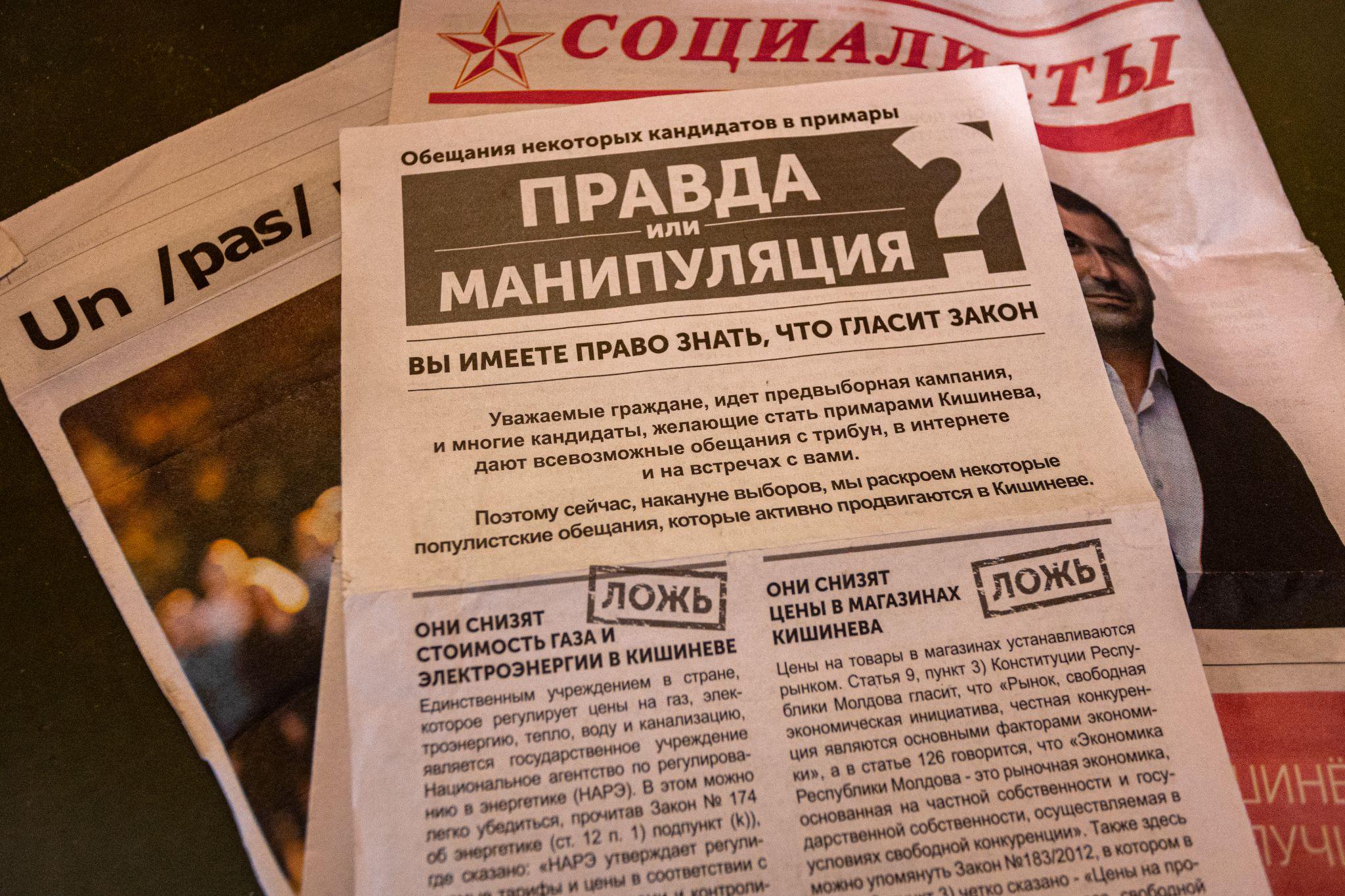

In a recent initiative, the Moldovan government has responded to pro-Russian disinformation campaigns by launching a robust communication effort with the distribution of flyers in Russian to underscore the impracticality of pro-Russian political promises. The aim is to enhance the credibility of government institutions and promote an informed public discourse.

These leaflets, promoting fact-checking in Chisinau's municipal elections, were focused on the law and specifically target populist promises made by pro-Russian parties regarding energy costs.

They emphasized that the mayor does not have the power to lower prices or increase wages, among other things. They also pointed out that some of the pro-Russian parties were previously in power and failed to keep their promises about the very issues they are criticizing today.

The fact-checking leaflets were distributed on the streets of Chisinau by pro-EU factions, aiming to counter disinformation and hold to account those who make unrealistic promises during the election campaign.

Pro-EU faction strengthens amid the government's crackdown on pro-Russian parties

Russia's hybrid warfare strategies have created a political landscape ripe for turmoil in Moldova, marked by deep polarization and heightened tensions, even during local elections of considerable importance.

On 5 November, Moldovan voters faced a crucial decision in electing around 900 mayors and 11,000 local councilors for a four-year term. The electoral process, closely monitored by 1,500 national and international observers, held immense significance as the country considers entry into the European Union.

In anticipation of potential pro-Russian protests in the capital, the Moldovan parliament has taken the step of banning members of the most extreme pro-Russian ȘOR Party from participating.

In June 2023, the Constitutional Court of Moldova found this pro-Russian Party to be unconstitutional after reviewing the corresponding inquiry from the government, Russian news agency Interfax reports.

According to the court ruling, the ȘOR party was acting contrary to the principles of the rule of law and posed a threat to the sovereignty and independence of the country.

The Șor Party was accused of receiving illegal funding and working on behalf of Russia.

Moldova’s intelligence chief Alexandru Musteață said that Russia spent about a billion Moldovan lei ($55.5 million) to overthrow the democratic government and destabilize the situation in Moldova.

Speaking at a news conference, Musteață said Russia had tried to use a criminal group led by fugitive oligarch Ilan Shor, founder of the Șor party, to influence the outcome of local elections in Moldova.

Ahead of the election itself, Moldova banned Șansă, another pro-Russian party believed to be affiliated with Shor.

As a result, the primary opposition in these local elections was the Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova (PSRM).

With communist, pro-Russian, and anti-European ideologies, the PSRM embodies the interests of the oligarchy and represents a significant force in Moldovan politics. The party's positions run counter to pro-EU interests.

They are also staunch opponents of the Romanian language and reinforce the notions surrounding the separate "Moldovan language and ethnicity" that was fostered by the Russian Empire after it annexed what is currently Moldova in 1812 in order to weaken and divide Romanian nationalism.

Particularly, the PSRM slams recent Moldovan intentions to amend Article 13 of the Constitution, replacing the term "Moldovan language" with "Romanian language," seen as alignment with Romania over Russia. This a very important symbol because linguistically, the language spoken in Moldova is essentially Romanian written in Cyrillic. The term "Moldovan language" emerged from historical Russian policies aimed at Russification and denying a common Moldovan-Romanian identity to undermine Romanian statehood ambitions and solidify control.

The ban on the activities of pro-Russian parties, as expressed by a supporter of the Socialist Party of the Republic of Moldova (PSRM) in the streets of Chisinau during a flyer distribution, has not weakened their resolve. "It can't bother us," remarked the activist, stressing that if the party is banned, "they are ready to create new parties" similar to the current one.

On the other side of the street, the stand of the pro-European PAS party (founded by President Maia Sandu) attempts to discredit the PSRM party and highlight the populist ideas of the pro-Russians. "In our country, the pro-Russians are nothing but destruction, clinging to the mentality of the Soviet Union and perpetuating inhuman conditions," laments Mihaj, a PAS activist.

He laments that "they don't want to change anything," reflecting the frustration among those aligned with the pro-European movement, who aspire to bring Moldova more in line with European values and standards.

Mihaj underscores the nation's desire to integrate with the European Union, with a resolute commitment to meet the stringent standards necessary for EU accession.

In this issue, Moldova has moved forward, having received the European Commission’s backing for opening negotiations on accession to the EU, along with Ukraine and Bosnia and Herzegovina three days after the local elections.

Their results also appear to strengthen Moldova’s EU aspirations.

Maida Sandu’s pro-European PAS received moderate yet clear support from the voters, winning 19 out of 32 regions across the country, up from 11 in 2019, and receiving 291 mayoral positions, which accounts for 32.5% of the overall mayor mandates in the country. The expansion of local support follows PAS’ remarkable achievement in the 2021 parliamentary election, when the party won a landslide victory, securing 52.8% of the votes and receiving a supermajority in Parliament.

However, PSRM came in with a strong second, securing 16.1% overall mayoral positions in the country and ten regions, mostly in the economically disadvantaged north – down from 17 in 2019.

While other major opposition parties do not explicitly endorse pro-Russian stances, they do voice reservations about Moldova's bid for EU membership. Radio Free Europe notes that the fact that incumbent mayor Ion Ceban has been reelected as mayor of Moldova's capital is a potential setback for pro-Western President Maia Sandu‘s party as the government is pushing reforms to advance the country's candidacy to join the European Union and distance itself from Moscow's influence.

Although declaring pro-Europeanness, his party, National Alternative Movement, is accused of having funds and advisors from Russia and pursuing the goal of winning over the conservative and pro-Russian electorate of PAS.

The absence of an absolute majority for any single party in the Chisinau City Council and PAS' loss of other major cities hints at a forthcoming era of intricate negotiations and collaborative governance.

Moldova’s pro-EU aspirations will be put to the test in the upcoming 2024 presidential elections, in which Sandu will not be eligible for re-election.

Moldova, stage of a geopolitical struggle

In recent years, the country has experienced pro-Russian protests that have raised questions about Moldova's resistance to Russian influence.

These protests, often featuring paid babushkas, were far from spontaneous events; they appeared to be part of a coordinated campaign from Russia to augment their influence in the country. Furthermore, insights from the Khodorkovsky Center suggest the existence of a comprehensive plan for a hybrid takeover of Moldova through actions involving the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) before 2030. Russia's militarization of protests is an integral part of its hybrid warfare strategy, designed to operate below the threshold of conventional war.

On the one hand, Moscow is manipulating the Moldovan energy market, raising natural gas prices and threatening to cut supplies, impacting the economically vulnerable population. On the other hand, it orders its proxies to incite demonstrations against the pro-European government, falsely attributing gas price increases to power while financially encouraging the demonstrators.

According to US intelligence reports, Russian actors linked to intelligence agencies plan to organize and exploit the protests to foment a manufactured insurrection against the Moldovan government. Ukraine has also alerted Moldovan authorities of Russia's intentions to overthrow the current government and replace it with a pro-Kremlin administration.

Since its independence in 1991, “the Republic of Moldova always was under the hybrid rule of the Russian Federation, in order to impose its domination over this country,” Minister of Defense Anatolie Nosatîi tells Euromaidan Press.

The Transnistrian war, which broke out in 1992, was the culmination of tensions between Moldova and Russia. Triggered by territorial and ethnic disputes, it was also driven by Russia's ambitions to maintain its influence in the region. The war resulted in a fragile status quo, with Transnistria functioning de facto as an independent state, although without international recognition.

Nowadays, some 1,500 Russian troops are stationed in Transnistria as part of a peacekeeping mission. It also holds large stocks of weapons inherited from the USSR (estimated at over 20,000 tons in the Cobasna ammunition depot).

That issue is like a sword of Damocles hanging over Moldova, allowing Russia to put pressure on Moldovan authorities militarily. “We call for the immediate evacuation of Russian troops as well as the evacuation of all ammunition and military equipment that are illegally stationed on the territory of the Republic of Moldova,” says the Moldovan Minister of Defense.

This complex situation contributes to Moldova's instability and raises concerns about its future, especially as the region is at the crossroads of major regional and geopolitical tensions, considering its proximity to Ukraine.

The EU, a way out?

As a countermeasure to mitigate Russian influence, President Maia Sandu has prioritized closer alignment with Western powers, making it a cornerstone of her administration's policies. This strategic shift towards the West, including Ukraine, reflects Moldova's resolute stance to bolster its ties with Western nations.

"We've implemented NATO standards in the majority of our military."

Anatolie Nosatîi, Molodovan Minister of Defense

Anatolie Nosatîi also expressed Moldova's unwavering determination to align with Western values and institutions. He emphasized that Moldova is a European country with shared European values among its citizens, "More than 60% of our citizens clearly determined to become a full member of the European Union," he says.

Mr.Nosatîi underscored the multitude of benefits Moldova anticipates, from economic advantages to enhanced security within the EU. Transnistrians would not be excluded: "In EU accession, we treat all citizens, including those on the east bank of the Dniester, equally," the minister stated.

Moldova's relationship with Ukraine has strengthened in recent years since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. The two countries have cooperated on various fronts, such as security and trade, and have benefited from the West's support in countering Russian influence.

"We have felt the consequences of the war immediately," he said, emphasizing that his country felt the consequences of the war from day one. Collateral effects of the conflict, he noted, have a profound impact on Moldova and its citizens.

Moldova's cooperation with NATO since 1994 has been instrumental in transforming its armed forces. Nestati highlighted the adoption of NATO standards in the majority of their activities, fostering interoperability with strategic partners. Moldovan troops have participated in NATO-led operations and training activities, further solidifying their ties with the alliance. In the Minister's own words, "we deploy our troops to NATO-led operations as per NATO standards and European Union integration will definitely require the integration of all security and defense forces to become a member of the same security architecture”.

Moldova stands at a critical juncture where it balances its historical ties with Russia and its aspiration to join the European family. As Nosatîi observed, “the current situation doesn't indicate an imminent Russian military threat, thanks to the success and sacrifice of Ukraine's armed forces.”

Related:

- Moldova excludes pro-Russian party from local elections

- The spectre of the FSB haunts Moldova, next target of Russia’s hybrid war

- Moldova spy chief: Russia paid fugitive tycoon $ 55.5 mn to overthrow government

- Insider: Deported Moldova Sputnik chief revealed as career GRU spy

- Russia planned to take control over Moldova by 2030 – investigation

- Pentagon sends military aid to Moldova to bolster defense capabilities