Since Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, approximately $300 billion in Russian central bank (RCB) assets, nearly half of the Kremlin's foreign reserves, has been frozen by the United States and other Western nations.

The idea is clear: Russia must be held accountable for the almost $900 billion in documented damages caused to Ukraine as of March 2023. The ongoing war, coupled with Russian “scorched earth tactics,” continues to ravage Ukraine's economy.

Despite the UN General Assembly holding Russia accountable, these frozen assets remain untouched, imposing a financial burden on Ukrainians and Western partners.

Amid debates among Ukraine's allies, opponents resist confiscation, pointing to legal, economic, and political concerns. The core issue, as highlighted by Tetiana Shevchuk, a lawyer from the International Center for Ukrainian Victory (ICUV), is the absence of political will in Western countries.

"Everyone fears escalation from Russia, no matter what form it takes. Furthermore, after the war ends they expect to continue business as usual with Russia. But if they confiscate this money, the Russians will take offense and refuse to deal with them," Shevchuk told Euromaidan Press.

The lack of political will to seize these assets raises concerns about potential reclamation by Russia for further war crimes. Euromaidan Press, in partnership with the ICUV, delves into the complexities, exploring why seizing Russian assets is not only legally justifiable but also a political imperative.

How much Russian assets are actually frozen?

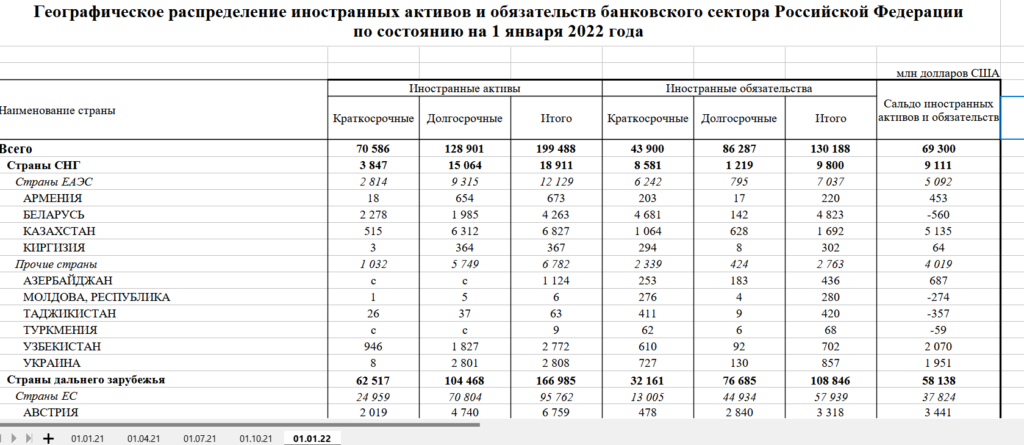

Quantifying the exact value of Russian assets blocked in Western nations proves challenging, as such information is not readily disclosed by Western authorities. The reported $300 billion figure originates not from Western sources but from a pre-invasion report by the Central Bank of Russia.

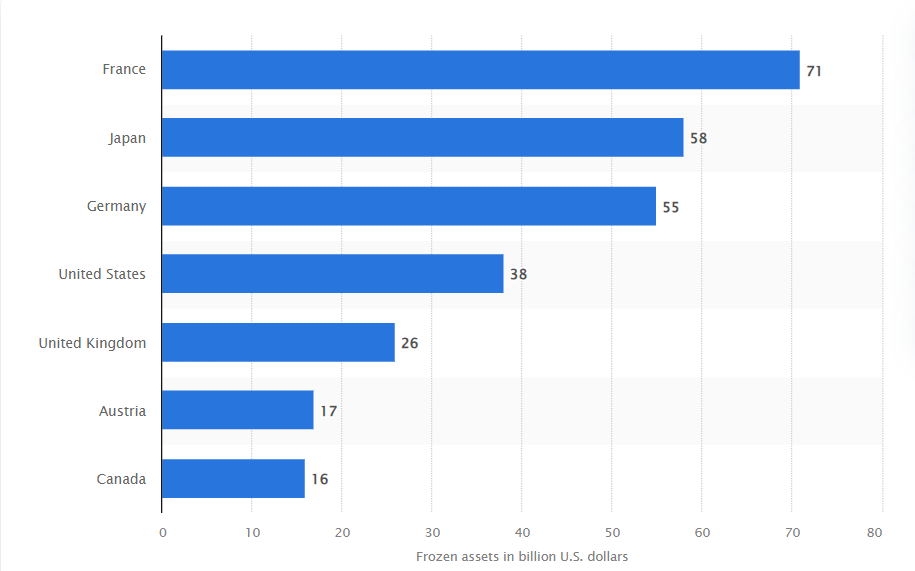

Over $214 billion of sanctioned Russian assets are estimated to be in the EU, primarily held at the Belgium-based Euroclear clearinghouse. Euroclear serves as an intermediary for European banks, managing transactions. Initially frozen Russian funds were placed in various European countries, specifics undisclosed by Brussels. Statista's calculations offer an approximate breakdown.

Value of assets of the Bank of Russia frozen due to sanctions due to the war in Ukraine as of March 2022, by country (in billion US dollars)

Ukrainian analysts, such as Tetiana Shevchuk from the ICUV, are more cautious in their estimates. She suggests that Russian sovereign assets in the US amount to $8-11 billion, and in Canada, it's approximately $1 billion. The discrepancies in data are explained by Russia's pre-war financial maneuvers, slowly withdrawing funds abroad, without anticipating the subsequent freezing of assets. Furthermore, Western countries often present convoluted information, incorporating frozen funds of Russian oligarchs and dubious transactions into the overall figures for Russian assets.

"As soon as a country, for example France, comes out and says: 'Yes, we have $70 or $80 billion of Russian money here,' it will immediately face demands to do something with it. Therefore, everyone prefers to hide behind a veil of uncertainty," Shevchuk explained to Euromaidan Press.

Hence, one of Ukraine's requests to the West is to audit the frozen Russian state assets, providing clarity for Kyiv on where to direct its inquiries.

Tracking Russia's $300 billion: global developments

On 17 October 2023, the European Parliament endorsed a €50 billion Ukraine facility, paving the way for the confiscating of Russian assets through collective countermeasures and collective self-defense.

Yet, Brussels has not addressed the confiscation of Russian assets for Ukraine. The only consideration is the use of profits from sanctioned Russian assets, which generated nearly €3 billion during the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Belgium has committed to investing half of this amount in Ukraine's reconstruction next year, leaving the fate of the remaining funds uncertain.

“We are working together with the European Commission to see how the legislation can be changed. We hope progress can be made. If at some point access to those proceeds would be legally possible, of course we will be an enthusiastic partner in that,” said Belgium Prime Minister Alexander De Croo.

Behind closed doors, however, European politicians are discussing a different narrative. According to Bloomberg, prominent EU nations such as France, Germany, Italy, and Belgium are urging caution in hastening initiatives to allocate proceeds from sanctioned Russian assets to aid Ukraine. In a private meeting with the European Commission on 8 November, these countries leaned towards an even more gradual approach, proposing a non-legislative document to assess options carefully. They aim, they say, to ensure the legal validity of using profits from frozen Russian assets without risking financial stability.

Canada is actively pursuing amendments to its Special National Laws, blocking the seizure of sovereign assets through court procedures based on the immunity of foreign states.

The US, under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), grants the President authority to block, compel, and transfer relevant Russian assets. President Biden, having declared national security emergencies due to Russia's aggression against Ukraine, can logically transfer Russia's frozen funds to Ukraine, similar to President George H.W. Bush's action with Iraq. The House Foreign Affairs Committee approved a bill on 8 November for the same purpose, and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen supported taxing profits on frozen Russian assets in G7 countries.

While intermediary scenarios, like transferring proceeds from blocked assets or imposing taxes on companies benefiting from Russian assets, are welcome initial steps proposed by Ukraine's partners, they shouldn't be the ultimate goal. Given the extensive damage, these measures should supplement, not substitute, total confiscation.

"We had [a] budget gap of $40 billion. It was last year, this year we managed better, and now [there is a] 5% increase in GDP but anyway we have a big gap. If we use only interest from all [this] frozen money, we can close about a half of this gap," Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy told Reuters.

With total confiscation, G7 and EU partners would avoid the ongoing challenge of collecting funds for Ukraine annually, amounting to tens of billions, which is neither realistic nor an attractive long-term approach.

Legal arguments: Overcoming sovereign immunity under customary international law

The customary rule providing jurisdictional immunity to a foreign state's property is seen as a hurdle to confiscating Russian assets under international law. Critics argue that Russian state assets enjoy sovereign immunity, supported by the 2004 UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and the International Court of Justice. However, in-depth analyses done by the ICUV suggest that sovereign immunity is not an absolute barrier and may be overcome in the Ukrainian case.

-

Sovereign immunity shields foreign state assets from court-ordered confiscation, but not from executive authority-issued orders.

International instruments and their commentaries clarify that sovereign immunity is limited to court judgments, excluding executive actions by one state against another. While crafted to prevent national courts from judging foreign states, this custom doesn't impose a general restriction on states applying policy measures in international relations. State practice indicates that challenges to asset freezing by the USA and EU—executive measures—based on violating sovereign immunity are rare, with states opting for alternative arguments.

-

Confiscation of sovereign assets is a legal collective countermeasure to Russia's violations of international law.

The European Parliament justifies confiscating Russian state assets under customary international law as a collective countermeasure to Russia's violations of the prohibition against wars of aggression. In customary international law, rule enforcement relies on countermeasures.

Trending Now

Russia's blatant violations of international law, encompassing the UN Charter, international humanitarian law, and human rights law, are evident. The UN International Law Commission's Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts empower injured states, such as Ukraine, to apply countermeasures.

Given Russia's egregious violations and escalating damages to Ukraine, the initial G7 sanctions and freezing of Russian assets are insufficient. More robust measures, including substantial confiscation, are justified and proportional.

Confiscated assets could serve as compensation owed by Russia. Compliance could lead to deducting their value from the owed amount, ensuring reversibility.

“There is simply no basis for saying Russia can violate Ukraine’s sovereignty while invoking its own sovereignty as an inviolable shield,” Laurence Tribe, Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard Law School, believes.

Key principles assert that countermeasures must correspond to the injury, and Russia has obligations to cease aggression and provide compensation; confiscated assets need not be fully returned until reparations equal the full scale of damage.

-

Confiscation of sovereign assets is a lawful act of collective self-defense

The European Parliament, in its draft resolution for the Ukraine Facility, justifies the confiscation of Russian state assets as a measure of collective self-defense under Article 51 of the UN Charter. This aligns with the Parliament's earlier call for collective self-defense, urging EU Member States to provide weapons, share intelligence, and implement non-military measures like economic sanctions.

Russia's aggression, causing a 29.2% GDP decline in Ukraine, justifies transferring frozen assets as an act of collective self-defense. Legal justification can be based on the EU Military Assistance Mission Ukraine's mandate, supporting Ukraine's right to self-defense. EU Member States can confiscate Russian assets to aid Ukraine's exercise of this right, meeting the criteria of necessity and proportionality.

In a broader context, NATO recognizes Russia as the most significant threat, emphasizing the importance of supporting Ukraine in preventing future aggression, aligning with G7 and EU interests.

Economic argument to confiscation Russia’s frozen assets: there’s no alternative to Western reserve currencies

The fear of destabilizing Western financial systems, often highlighted by central banks and finance ministries, lacks substantial support, according to another report by the ICUV. The argument hinges on the absence of a viable alternative to US, EU, and Japanese currencies as global reserves.

Even authoritarian countries, holding nearly 40% of global foreign exchange reserves, prefer the stability of free-world currencies.

China, aspiring to establish its currency as an alternative, faces challenges, exacerbated by the weaponization of the yuan in trade wars. The full-scale Russian invasion further weakened China's position, with freezing Russian assets leading to a decrease in investments.

Other attempts to establish reserve currencies face even more challenges: India's rupee struggles with convertibility and government interference; Russia's ruble has lost 40% of its value since 2022, discouraging investments. The rumored BRICS currency encounters geopolitical, economic, and cooperation challenges, reducing its likelihood of widespread adoption.

Concerns about seizing central bank reserves may prompt some countries to consider moving them into physical gold. However, gold's volatility, high costs, and limited convertibility make it impractical.

Even if all authoritarian countries decide to repatriate gold, the global supply is insufficient. Central banks hold about 36,000 tons, valued at $2.14 trillion, while authoritarian countries' combined reserves in foreign currency and gold amount to $5.35 trillion. Flocking reserves into gold would increase its value, trapping authoritarian regimes in golden cages and limiting their role in global trade and international settlements.

How to mitigate potential risks of confiscating Russian assets?

Opponents of confiscation argue that Western currencies' key strength lies in predictability and stability due to effective institutions. While true, this doesn't mean the West cannot use funds from the aggressor state to compensate for damages in Ukraine's self-defense against the largest war of aggression since World War II. Predictability doesn't equal inflexibility; justified steps should be grounded and explained.

To minimize risks and avoid "de-dollarization" or "de-euroization," a joint effort by the G7 and EU to confiscate Russian frozen assets is crucial. Establishing legal mechanisms with clear criteria related to Russia's war of aggression signals that the confiscation is justified, not arbitrary.

“The idea is to do this multilaterally. If others didn’t, there might be a flight from the dollar. But if it is done by all the major currencies, where are people going to move their money?” said the former US Treasury secretary Larry Summers.

This would send a message to other countries that they need not feel threatened if they don't plan wars of aggression. If authoritarian countries withdraw reserves, it may signal potential preparation for gross violations of international law. Instead of fearing repercussions, the West should view this precedent as a safeguard against future wars of aggression.

Read more:

- US Congress approves bill on transfer of Russia's frozen assets to Ukraine

- Belgium commits €1.7 billion for Ukrainian aid from taxed frozen Russian assets

- NYT: US may use legal mechanism to transfer frozen Russian assets to Ukraine

- Why the West does not confiscate Russian frozen assets in Ukraine war