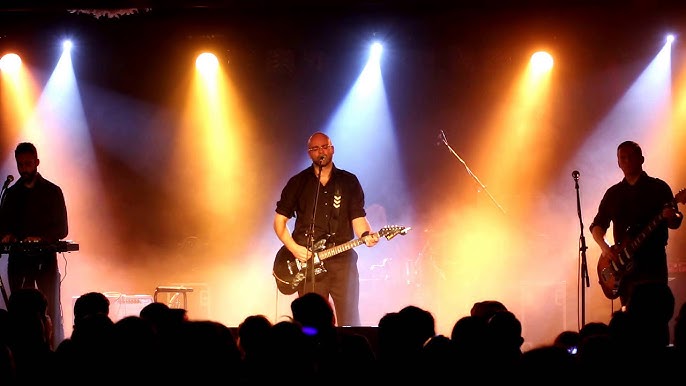

Jerome Reuter was performing in Kyiv just days before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In the months after the invasion, Reuter returned to Ukraine multiple times, performing benefit concerts and raising donations for the Ukrainian military. He is perhaps the first foreign artist to perform a full live set in Ukraine since full-scale invasion began.

Now his new album Gates of Europe chronicles the war’s first year in haunting neofolk ballads that convey the anguish, defiance, and flickering hope of a nation under siege. “This is a terrible day for Ukraine and a dark day for Europe,” a voice declares amid the cacophony of sirens and explosions opening Jerome Reuter’s latest work.

We talked with Jerome Reuter about the inspirations and motivations behind his musical tribute to the Ukrainian people’s struggle.

You’ve been in Ukraine shortly before the full-scale invasion in February 2022. Was it your first time in Ukraine? And what was your experience in Ukraine days before the full-scale war began?

It was not the first time. We have been visiting since 2015 – mostly for shows in Kyiv but also in Odesa. And then in 2020 or so we were supposed to play and it didn’t work out because of COVID. We were supposed to play in November 21 but it was put into February 22. When it became known about the troops gathering in Belarus and all that was gaining heat. People told me not to go but I went anyway, though I wasn’t being courageous, I was just fed up with not being able to play because of COVID.

A day or two after I got home, there was news about the invasion. I always say I still had the dust on my boots [from Kyiv]. Obviously, it all felt very close, having just been there and since we have played in Ukraine regularly and we have many friends there.

It was just a natural thing to think about how to help. I’m not trained at weapons so we did a livestream from my home to raise some money. The promoter we were working with fled to Lviv with his family, took over a house and turned it into a refugee shelter. We supported that shelter. It’s called Lviv Host. Next, we thought about how to continue, how do we keep people interested in this? Because people grow tired and they don’t want to see the same thing. So we thought, if we do another stream, it should be special so that people still come and donate. So we did a live stream from Lviv in July last year. At that time I was still a bit unsure about how to travel there, how long it would take to cross the border. Then it was a bit more difficult still and so we didn’t go all the way to Kyiv or anything.

But when I played in Kyiv in February 2022 the crowd was so amazing, so I just needed to get back there ASAP. Of course, there was tension in the room back then already; and we have these songs about Europe and war and all of that, so it was darkly fitting. People were singing along a lot, because we have our small fan base [in Ukraine] – maybe even not that small anymore, – and it’s a good crowd. I told them I should record this live because they were really singing along beautifully. So I made the promise of coming back the following year and that was this February. 2023

When you were in Kyiv and Odesa shortly before the full-scale invasion, did you sense any signs or indications that war could happen? Did you perceive any tension, or did everything appear calm and normal?

I was warned not to go to Ukraine. Luxembourg is a small place and I have friends in some European institutions, and I cannot name names, but I had this one person tell me something that was worrying – and it turned out to be correct. Except for the time of the invasion, which was a little later than they expected, luckily for me. I didn’t know whether I should come to Ukraine. I thought Putin is just playing tough guy and it would be stupid of him to attack. And, well, it is stupid but he did it.

Whoever could, fled the Russians. They went back to Irpin to save the rest

Then in Odesa it was not really a big thing, and in Kyiv where I had a little more time to talk to people, most people didn’t really expect anything of that scale. They were worried, yes, but they told me Ukraine has been at war since 2014, anyway. It was clear that something would happen but I don’t think anybody from those people that I talked to was expecting this scale of invasion. I was honestly relieved when I was, on my plane back, still thinking that nobody knows where this is going. But of course, when I was flying to Ukraine, it was a very weird flight. I was the only non-Ukrainian and there was not a single woman on there. There might have been Americans, but it was very much like something will go down here, like we’re just calling back some troops or something. It was a very weird feeling there.

And then you play the show and there’s always a different energy. Most foreigners would leave Kyiv because they had been warned and also people were discouraged from traveling to Ukraine. So people were very thankful that I did not cancel the concert because they were kind of expecting me to cancel it. But I had had enough of cancellations, and I wasn’t gonna let the Russians ruin that.

What inspired you to create the album entirely dedicated to Ukraine?

I didn’t want to originally. It’s a really bad idea in my mind because I like to plunge into a subject matter in full and try to grasp the whole of the thing, as much as I can, judging things and putting it in context with history and philosophy. For this, you need a certain distance. And now I would only be able to deliver some sort of comment on things that are happening right now while there’s no way of knowing what will happen next week. It might completely change your narrative. It’s all these things that I would usually stay away from. Also, politics and music don’t mix too well in general. However, everything I would write would be about this [Russo-Ukrainian war]. Just nothing else was coming out.

I did a few songs first that just came out and I thought they were like a knee-jerk reaction – a physical reaction to all of this. I released them as a digital EP called Defiance. There were no plans to make a whole album then.

I thought, OK, this is it, I’ll just release it fast digitally because I didn’t want to make money by selling a release. I go to Ukraine, I do the donation thing, I support. I didn’t want to make this theme and be like, “Look at me, I’m singing about important stuff.”

But I still couldn’t stop writing about it because I’m very emotionally involved, especially as I keep visiting Ukraine and have more and more friends there now. Some of them very very close. It just stays with you. Also, the next album I’m working on is still very much related to events in Ukraine and Europe in general. I try to pull back thematically a little, but it’s still inspired by what’s going on in Ukraine and the world. As much as I didn’t want to, I had to write this album.

I’ve always wanted to know more about Ukrainian history, anyway, but that’s true for many countries. So it was very interesting for me to really start digging into it finally. We have different narratives about why this war is happening – the Russian propaganda, the Western view, where does Europe end, and so on. History is boiling right now. The day-to-day reality of Europe that’s been important in my work is on display. I would prefer it otherwise, but that’s how it is.

The subject of Europe plays a significant role in your music, not only in this album but also in your previous work. What about Europe as a theme captures your interest?

I’m from Luxembourg, so I grew up in an environment that’s distinctly European. We’re a very small country with very important, big neighbors. We’re locked in between France and Germany and could always witness them going back and forth to fight each other, basically. And then both became the engine behind the European idea. The backbone of European Unity. And Luxembourg was always supporting the European idea, anyway. I mean, it is not that we could frighten anyone off with our army. When I grew up, Europe was a reality of life – we had three currencies, three wallets we would use depending on where we were because the borders are so small.

I live in the south of Luxembourg; I can see France from my window and I’m not on the 20th floor or anything – it’s right there. Belgium is 15 minutes away and Germany is 20 minutes away. That’s how big we are. We always went to concerts or shops abroad. So this whole thing about languages, culture, and all came in a European package. I realized many didn’t grow up that way. I did a lot of traveling earlier with my dad in a theater company and it would take us to eastern parts of Europe as well. The world was smaller then in your mind – and as you grow up, things move further away. This fed into my obsession with Europe because I could see those people longing for what we had but people at home didn’t realize it or appreciate it at all.

This is even stronger now, with people falling back into nationalist agendas here to push this idea of unity out of the way. And in Ukraine’s case, you see this whole idea of freedom, democracy, and the European idea as part of the struggle, while at the same time having its own identity at heart. I think it’s tremendously inspiring to see you fight the way you do.

Obviously, the narrative often is – even here – that Ukraine is just a cousin or brother state of Russia, that they’re basically Russian. These ideas have been force-fed to us for decades. Ukraine’s political system is so young since independence, and people here often dismiss it. But your fight shows the value of freedom and democracy because you haven’t had it for long. And look how you fight for it! People in the West often think that their countries have been around forever and will remain forever. But that is far from the truth. Some of our nations were just as young as yours when we got dragged into world wars. This fight for a free Europe will continue.

Lines on a map can be drawn wherever, but it’s people themselves who decide where they belong. That’s the whole idea for me about Europe.

Were you inspired by Serhii Plokhy’s book “Gates of Europe” or other historical sources in your exploration of the historical themes in “Gates of Europe” album, given your evident deep dive into historical topics?

Yeah, I stole the title. Don’t tell anyone (smiles). I just thought it was such a significant description of this area on the map. There are other gates too, but it’s also the gates in the mind. I tried to read up as much as I could, and I’m still not finished. I think I consulted all the sources there currently are in the languages I speak. I have friends in Ukraine who were looking for me too, to find smaller translated editions of things.

But I didn’t need narratives too much because most songs were direct reactions to experiences during trips or what I saw, like the song “Yellow and Blue.” This is not a record about the whole history of Ukraine, but I nonetheless wanted to have an informed narrative on the record, because it’s all about finding the voice, if I want to be honest and authentic and help in a way. I didn’t want to be one of those Westerners who – and it’s a very tricky thing – behave like, oh, there’s a war, let’s put on the sad face and ask for donations. Or let’s try to push it aside while blaming politicians. It’s a very touchy subject.

“Gates of Europe”: Luxembourgish band dedicates entire album to Ukraine’s fight

I usually base my work on personal accounts or personal experience. This was some of my very own, some of the people I talk to, and then I mix it all with whatever I can find in literature, and whatnot.

Unity is actually a perspective I hope many in Europe share regarding the Ukrainian struggle. Sometimes, the European idea is misconstrued as emphasizing compromise, particularly in coexisting with Russia, “Ukraine’s older brother.” Some view Ukraine’s efforts against invasion as nationalism and not as struggle for national identity and freedom. How is it in your country? How do people interpret the European idea concerning Ukraine?

It’s a very complex thing. But it is safe to say that this conflict has challenged everyone. Both on the left and on the right and anyone in between. Many of us have had to rethink our allegiances. For me, it was the obvious, natural thing.

For many years, the left wing was fed the narrative that the biggest threat to European democracy comes from Ukrainian nationalists. They need their daily evil nazi thug. And so they kept telling people that all of Ukraine is run by right-wing extremists in the army and government; that it’s a right-wing coup, Zelenskyy is Jewish so that’s just proof they hate themselves – this sort of none-sensical narrative. So the left-wing likes the idea of fighting for freedom, but then there’s the national idea and nationalism, which they don’t like. “Oh, this is nationalism, I cannot support this.” But then again, it’s for freedom.

And then you have the left in Germany, where Russia is seen traditionally as the big brother of Ukraine, and the motherland of glorious communist ideas. They have a hard time accepting Russia is bad, which is also happening on the right wing – this idea of Russia fighting for traditionalist values and the old multipolar world order. Obviously, these people have never been to Russia.

What I’m saying is this war reveals things we’ve been misled about. Like the European right has also eaten up the Russian narrative because Russia has poured money there for a long time and spread dissent to weaken the democratically elected governments. It’s funny how German nationalists are pro-Russian when that’s the worst thing ever in their ideology. But their hatred for the US overrules everything, – the supreme evil for them.

The mainstream talks pro-Ukraine, but sometimes it sees it as a way to get rid of old weapons by sending them to Ukraine – to produce new ones and sell them to Ukraine again. So to say, we’ll make money fighting Russia but avoid real problems if we actually win. So, let’s just feed enough weapons to keep Ukraine going.

But I’m getting a lot of criticism for just siding with Ukraine completely. Some think I am some NATO bot now or US-bootlicker. But I don’t think the US is a peace-loving saint. They act as every power acts out of self-interest. I am simply on the side of Ukraine in its fight for Independence. So that Ukraine may gain its rightful place as a free nation in Europe.

What I’ve been trying to do is just look at it from the Ukrainian side, which is always dismissed here. It’s like either you’re just doing what the US tells you and Zelenskyy is a puppet or it’s this other narrative coming from Russia, about multi-polarism, traditionalism, and so on.

I think the real thing is Ukraine itself and the way you are fighting this. Who knows how it’s going to endö it’s still completely open in my mind. I cannot make any predictions because all of my predictions were very wrong in the past. But for me, as someone from far away in Luxembourg, one thing I can do for people here is to make them aware.

Many in Western Europe have been fed the Russian narrative that whatever the mainstream says here must be wrong because the mainstream did say a lot of different things that were wrong indeed, though they didn’t necessarily lie all the time. But society is what it is, and the mainstream media is not trusted as much anymore. So if the media says we have to support Ukraine, people think it’s probably not true.

What can help is making people aware that Ukraine is an actual thing in itself, not some weird half-cousin of something bigger. It’s about making people aware Ukraine is a nation with its own history.

You’ve been visiting Ukraine since 2015, when there was the war in the east of Ukraine, but still other cities remained relatively calm. Can you reflect on the evolution of your ideas, attitudes, or stereotypes about Ukraine and Ukrainians from that time to the present? How has your perception of Ukraine developed over the years?

Well, in 2015, I didn’t really know that much, to be quite honest. I heard in the news about the Orange Revolution and Yanukovych. But for me back then it was like a case study, you want to know what’s happening and understand who is who and where on the map, but it still felt quite far away.

Ukrainian music about Russia’s war: a tale of struggle, pain, power, and courage

I hadn’t been to Lviv before the war, we always flew straight to Kyiv and then to Odesa via Poland, never travelling through the rest of Ukraine, really. But having done that a few times now, I get a much clearer picture, because the more you travel in a country, the more you get a sense of the place and people. And the slower the better – walking is best, but even in a van, on bumpy roads, you get a feel for the nation and its inhabitants.

In 2015, we weren’t coming to Ukraine feeling it was a war zone. We knew what was happening in Donbas, some sort of war that wasn’t being called that. Maybe two years later, someone gave me a photo book called “War it is” and a bullet from the front, saying there is a war going on, Jerome, you should know about this. And when we arrived at the airport in 2015, there were huge banners with photos of fallen soldiers and recruiting posters, high security and military with machine guns, which contrasted with Paris or Berlin at the time. It wasn’t because of terrorism but an actual war. So, we were suddenly in a society where war was real. And not just a cultural one.

I’ve been to Israel before and after so that’s different, it’s permanent war. But across the subsequent trips to Ukraine over the last 10 years you could really see the movement towards the West, changes in people’s attitudes, the streets, architecture – which isn’t necessarily great, I hope Kyiv stays Kyiv even with Starbucks and McDonald’s moving in harder. But it was clear people wanted less association with Russia, this cultural war was becoming more pronounced, and the invasion seems a logical step from the “big brother” to regain control because Ukraine was showing it wanted its own future, not the past.

If someone from Europe, unfamiliar with Ukraine, were to ask you, how would you describe Ukraine to them?

I’m still learning about Ukraine – the language and all that. So much is still in the dark to me. But I would emphasize that Ukraine is its own nation, country, and identity. That’s the main problem with our arrogant, almost racist way of viewing the East – the notion that it’s all former Soviet territory, though the Baltic states are accepted more now since they’ve been in the EU longer.

There’s this lingering narrative of it all being Soviet land – that before, there were just some minor kingdoms, and then there was Russia. It was all Russia with a few tribes speaking varying dialects. That’s such a ridiculous concept, yet I still see it in people’s mentalities here. We are just set in our own ways and look at things from our own corner. When I talk with friends from here about their neighboring countries or their exchanges with cultures nearby, like Georgia or Armenia, I realize Ukraine has its own entire world too. We are very self-centered in the West.

You’re donating all proceeds from your tour to the Ukrainian military, which is a huge commitment and contribution. What exactly motivated you to do that? And could you share some details about who you’re supporting in particular?

So, the first thing we supported was our friend, someone we knew. We could see the impact, what he was purchasing with the funds we received. When situations like these arise, or when there’s an earthquake or something similar, screens are always filled with account numbers to send money to, trusting that it will reach its destination. Many people here are often quite anxious, wondering if the money will ever arrive where it is needed.

Our involvement in actual travels to Ukraine during the war led people here to place trust in us. They knew, ‘We’ve seen the pictures, we know you’re genuinely going there.’ So, they are confident this money will reach its intended destination.

So, my friends in Ukraine and I directly supported some of the units of Ukrainian army. There are these constant crowdfunding initiatives specifying precisely what the unit needs at that moment. It depends on the season, weather conditions, and various other factors to really assist the soldiers. It’s one thing to help shelters, and all those important causes but, you know, there’s no point in pouring money into a shelter if you can get rid of the actual problem. And that’s the people on the front doing that. But we’ve also supported military hospitals and such.

We’ve worked with different drivers, both from Poland and the new one is more involved on the military side of things, primarily bringing medical aid to frontline hospitals. We kind of go with the flow in our own circle; when we meet someone we trust, we’ll allocate the money accordingly. It varies each time, going to different recipients, supporting various military units.

Outside opinions, especially in the West, often question why we’re directing funds towards the military. People want to help dogs, children, and the elderly, and it’s not always clear for them why we’re also giving to the military. Some people are hesitant to provide funds to those they consider “murderers,” which is a ridiculous notion. There’s no need to help fund shelters if there is no war because you guys ended it. But in public opinion, we’re pacifists; we prefer to provide bandages to those injured. We don’t want to get rid of the problem.

Do people in Luxembourg and the surrounding areas where you live have distinctive perspectives on the events in Ukraine? In Ukraine, we often distinguish between various European viewpoints, including those of the Baltic countries, Poland, and Germany. How would you characterize the viewpoints of people in Luxembourg?

Luxembourg having no army to speak of, really, there is not an awful lot we can provide you with. We do have one battleship because we are a part of NATO. So we’re required to have one battleship and one fighter jet or something. And because we don’t have a harbor, our battleship is stationed in Belgium. So we are kind of out of the discussion when it’s like, “ok, do you have any F-16s?” Nope, we’re out, but we’re sending money. What we did was send a lot of items, such as fire engines, ambulances, and such We also sent some military equipment. Our policy is quite clear, and there were never any major polemics about whether to support Ukraine or not. Except the communist party here who is against delivering weapons to fight against Russia. And a lot of the people on the left, like in Germany, who think not sending weapons will miraculously bring peace and appease Putin.

I lived in Germany for many years and spent some time in England as well. It’s interesting to note that the English, perhaps due to the London real estate situation, have developed a dislike for the Russians, I do not know. I’m not sure if it’s some sort of revenge for London, but they are genuinely supportive, which I’m thankful for. With the English, it’s always a bit tricky to determine whose side they’re on. They don’t particularly like the French or the Germans, but they do have a history of following the lead of the US. It seems like when “Big Brother” or America is involved, they’re on board.

We should be asking what feature of Russian politics is not fascist – Timothy Snyder

I am from Luxembourg, yes, but I’ve never claimed to represent my country. Our society in Luxembourg is quite unique in that we have more foreigners living here than “natives”. And a lot of the communities here are also from Eastern Europe,so they know what it is like to have Russia as a neighbour and do not think twice about supporting Ukraine.We even played at a charity festival for the Ukrainian Association of Luxembourg, quite a strong expat community here.

Do you have Ukrainian roots?

No, no family ties or roots whatsoever. I’m innocent (smiles). I’m actually quite rare because I’m fourth-generation Luxembourgish, which is very uncommon. I think there are a hundred of us or something. Most of my friends have Italian or French ancestry. So we are a wild mix here.

You’ve mentioned that your songs about Ukraine are mostly a direct reflection of events, but I noticed that there are some inserts or citations from other sources. For example, in the song “Eagles of the Trident,” whose words were featured at the beginning of it?

“Eagles of a trident” that’s just from some movie in German. I have heard some people say it is a Hitler quote or something – that is absolute nonsense. It’s not really anything other than harsh words which mean basically “only through hard battle.” But I think you meant “How came Beauty…” where there is a longer passage in German, that basically states that sometimes democracy has to show its teeth in order to defend itself.

[As a soldier] you just decide that you serve to protect, and sometimes we have pledged to serve against violence with violence – because sometimes the Good needs violence too.

We’ve all seen war in the history books and we know it’s a terrible thing which we should avoid it. But there’s this thing on the left who just have this pacifist reaction to any armed conflict. And say no violence is ever needed. So we just let the other guy take over because he doesn’t abide to the “no violence war”. Sometimes you just need to imagine yourself being in the situation of Ukraine.

You guys are losing your best people in the fight against somebody else’s worst. They [Russians] send in millions of people. It’s this super ridiculous waste of human life that they throw them away as a wave of violence towards the freedom loving country, which has to lose their best in the defense of it.

You also had a lot of some Ukrainian words and phrases in your song. Did someone help you, one of your Ukrainian friends, to choose them? Or do you understand Ukrainian a little bit yourself?

No, I really don’t. I understand some words and phrases, and I tried to talk a little bit on stage – very short sentences that I tried to memorize. But I don’t really know the language. I’m trying to learn the language but it’s very hard because all the people I know there are very happy to talk to me in English so they can practice. It’s very hard to learn a language when you don’t hear it every day.

I’m kind of learning Italian on the side because I just love the country, and I’m not really fluent but I listen to the radio, and it’s very easy for me also because there are lots of Italians living in Luxembourg. But with Ukrainian, it’s so far removed linguistically from the languages I know.

So yes, I had friends help me with the lyrics and phrases, and also other friends who helped me get recordings of spoken Ukrainian. A lot of people sent me stuff from the front. I didn’t use all of them of course, but, like I said, we have our audience in Ukraine, we’ve had them before the war, and they know how we operate – that we use samples and snippets, and try to mix them in because I love this multilayered thing. It’s a good way of making different opinions clash when you have the main vocalist saying one thing and then you have this other perspective flying in from the side saying something different, and the languages just mix together.

So people just assumed I would do an album about it, and they sent me stuff. There’s this one recording of a drone strike that somebody sent me. It’s really weird when you get sent stuff like that – it just takes on a whole different reality.

I came across one of your songs that paraphrased the words of Rudyard Kipling. It was about the topic of immigration in Europe, the song called “Who Only Europe Know.” But it made me think in a slightly different direction about Ukrainian refugees and immigration here from Ukraine, and the hopes Ukraine holds that these people would return. Some Ukrainian experts now say that because we are losing people from Ukraine, we will need a lot of immigration into Ukraine after the war to help solve economic problems, even after the victory. So it’s quite a complex topic here, which is discussed a lot but in a very different context compared to Europe. Do you perceive this topic now differently, in the new context of Ukrainian refugees?

Migration is probably the hottest topic we should never talk about, for a variety of reasons. And that’s the last thing I would say is popular, but it’s certainly one of the more controversial issues, where people on the left interpret it one way and people on the right interpret it another way, and then they also interpret each other’s views in their own way. It’s a big mess, which is good because I think you should make people talk and think.

In that song, there were all sorts of sentiments, potentially problematic ones… But then again the repeating chorus is “What do they know of Europe, who only Europe know?” Which basically means, you need to step outside and see the bigger picture, look beyond Europe.

But it is a central topic of contention. And certainly, the war has twisted it a bit, you could say “immigration 2.0” in the discussion – because you could really see the huge difference in welcoming culture when it was about this war, versus say the war in Syria. Both wars involved Russia, but not the same effect on immigration here.

So of course, the reaction in Poland was very different than in Germany or further west, because there was no discussion there, while Poland, I believe they’re quite proud of saying they don’t accept other types of immigrants, you know?

And it’s an important topic because you can see where people’s values lie. And this war has really turned up the heat on things. Suddenly people are making a distinction between types of refugees, and there been a lot of things misrepresented in the media.

Ukrainian refugees: blow to Ukraine’s demography, godsend for the EU

But it’s a very different situation when a neighbor is under attack and people flee. There’s been this tendency to portray Ukrainians who travel back and forth between Ukraine and wherever they fled as just tourists profiting from help, then going back home. But if you know the Ukrainian reality, it’s no surprise and there’s nothing wrong with that.

The left and right are getting overwhelmed, with Ukraine turning things on their head. The left is like “Oh you had all these bad Nazi battalions and now we’re helping you, how horrible.” But then the right is like “Yeah they’re this and that, but hey, they look like us so they must be okay.” It’s a very weird hot topic.

But there’s the issue of what happens after – population decline is obviously a concern, but for me right now it feels wrong to even go there. The guys are still fighting. If things go right soon, and I hope you get all your land back and all that, then it’ll be up to Ukrainians to figure it out. There are a lot of challenges ahead either way. But you know, that’s life – the war is the thing right now that needs to be won, and that’s enough to deal with for the moment.

Whatever happens after, I’m afraid of Ukraine becoming too “McDonaldized” like Europe, where cities end up all looking the same – not like when I was younger and each place had such distinct character. Now you really have to leave the cities to see the real country.

That’s a global thing though, not like “Oh I hate immigrants because they make cities look different.” No, it’s not the immigrants’ fault. But it’s true you have to see the small villages and rural areas to really get to know a country.

By the way, did you get a chance to travel in Ukraine during your tours? As far as I understand you’ve been traveling by train or car lately?

Well, before the war, I was only flying to Ukraine. And now obviously that’s not an option. I’m really becoming an expert on the different border crossings between Poland and Ukraine. Every time we go there now, we basically use a new one because we usually carry humanitarian aid. Some of the border crossings aren’t meant for cargo loads but only for humanitarian aid. So we have to find a different one each time, which is actually better anyway, because the main crossings are just jammed with people. So that way we were traveling by van, because it was the safest way for us to travel.I’ve also gotten to know a lot about traveling by bus around Ukraine, from Kyiv to places out west.

And most of our travels now, like for these last shows before the war, I flew somewhere in Poland, then took the train up to Kyiv – a beautiful train ride actually, one of the nicest I’ve been on. I saw a lot of the landscape, which was very interesting – kind of reminded me of my first times in the US, where you get a different sense of space.

It doesn’t look the same, but just that feeling – because where I’m from, the houses are small, streets very narrow, towns are cozy. Then suddenly, you’re in this vast open space, this sense of emptiness. It’s almost an existential feeling, like that first time traveling through the wide-open frontier west, where you can drive for hours in a straight line without seeing another car. You feel like you’re dreaming.

Not quite the same in Ukraine, but that landscape I saw on the train ride down to Odesa – I was half asleep but the experience of all that space, the types of trees and meadows and such. Just driving around Ukraine, we got to learn more about it. We never took the same route twice. There was always some place we’d meet someone from the military to deliver aid, or a hospital off the main roads. So you realize the back roads can be very bumpy. But it gave more of a feeling for the country, compared to just flying in and seeing the airport, which all look alike.

Could you share your hopes for the Gates of Europe tour?

Last year we did a tour as well, and it was the first after COVID. So people were still a bit unsure about being in one room with so many others. And people didn’t really trust that events would take place as planned, because there were constant cancellations and changes due to COVID. But this tour did happen, it was the first one. And even just before that, after COVID wasn’t as much of an issue anymore, people were still kind of worried about it.

So this tour now is quite big. For me, it’s a big album in the sense that it’s very important to me personally, as it should be for everybody. It’s really about the here and now. So I hope people will come out to the shows, because I think, especially after the last tour, the shows we did in Poland and places like that – a lot of Ukrainians would show up. And they might bring a flag or something. It’s not just seeing them on TV as refugees, they’re actually here. They don’t really want to be in this country, they’d rather be at home. But there’s this appreciation, like, “Oh thanks for talking about this, and making this the subject of your work, because it keeps it in people’s awareness.”

Everything is emotionally heightened. And personally, I just hope everything will go smoothly – that we’ll make it to every show, because there’s quite a bit of driving involved. So when you ask what I expect – I don’t expect anything! I just hope we’ll get out alive.

Related:

- “Gates of Europe”: Luxembourgish band dedicates entire album to Ukraine’s fight

- Ukraine, the Gates of Europe of the last millennia, and their meaning for Russia – Serhii Plokhii explains

- Beyond Go_A: a playlist and guide to modern Ukrainian folk music

- Kyiv is becoming the world’s music video capital: 12 iconic clips

- Ukrainian music about Russia’s war: a tale of struggle, pain, power, and courage