The last two centuries have seen Russia controlling over 80% of Ukrainian territory. Despite a brief period of independence proclaimed in 1918, it was only in 1991 that Ukrainians could truly establish an independent state.

Today, the consolidation of the nation continues, even while restrained by the war in the Donbas, says Plokhii in a recent television interview.

“For the first time since 1991, there is a clear benchmark, a clear majority among our electorate regarding the orientation towards Europe...Before there were two groups [pro-Russian and pro-European] in the equilibrium of constant competition with each other. There is now a majority.”

He goes on to say that Russian culture in Ukraine becomes the minority, after a long period of Imperial and Soviet dominance. Plokhii emphasizes that this was not the case before the war.

"I am part of a campaign of historians in the public space," says Plokhii, describing the evolution of Ukrainian self-identity. “If before,” he says “my books were printed in Ukraine only if I contributed funds, nobody asked me to fund The Gates of Europe...I feel today more or less like a normal historian of Ukraine who does not have to pay for his texts to be distributed. It testifies to changes in society.”

To help clarify this shift in self-perception, Ukrainians needed an independent historical narrative—one not influenced by Imperial or Soviet propaganda.

The same can be said about the Western audience. When in 2014, Ukraine started appearing in the news rebelling against Russia, foreigners began asking: “What is Ukraine and where is its place among other nations?” The narrative of The Gates of Europe explores a question which has been relevant for at least 1,000 years.

Two frontiers in Ukraine

These two borders have made Ukraine a frontier country in a very unique sense. Ukraine is a country belonging to Europe, yet for centuries it served to buffer the continent from marauding eastern hordes. It was the outpost. Ukraine is also bound by two contending Christian churches—it is the frontier of Eastern Orthodoxy and Western Catholicism. During the course of history, the two churches were promoted for political purposes, respectively by the politicians of Russian and Austrian-Hungarian empires.

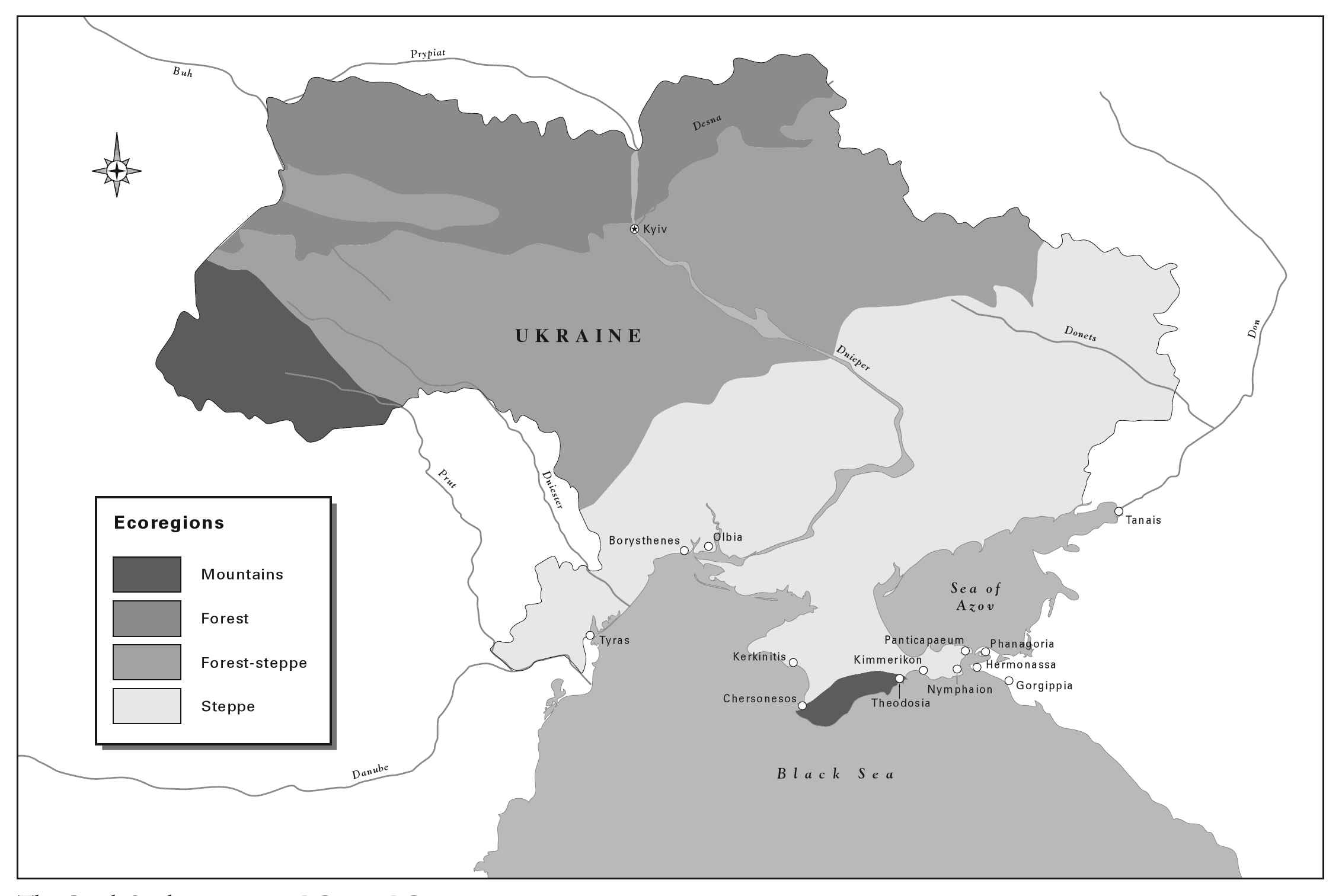

Ukraine’s physical terrain has always impacted the country, separating agricultural settlements in the northwest from cattle breeding and trade-centers of the south. This not only influenced the country’s economy, it also separated European civilization from what the ancients called the Wild Fields.

During the era of the Kyivan Rus, the natural contour of the land between the steppes and the forests de facto separated the people of the Rus from nomadic Polovtsians, culminating in continual battling between them.

In 1240, when the Mongol invasion of Kyivan Rus destroyed the state, this land contour was still important. It now separated the Golden Horde from what would soon become vassal states that were required to pay tribute to their occupiers. As a result, the outer band of the frontier extended further to the northwest.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the borderlines shifted again. Resettlement of populations and the restoration of central Ukraine had taken place. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian Kozak warriors had established their stronghold in the lower region of the Dnipro — Zaporizhzhia. The band pushed southward once again. Kozaks created their own settlements at the frontline of the Wild Fields to protect Ukraine from the Crimean Khanate — the remnant of the Golden Horde.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Ukrainians colonized the east, but in this same period lost the autonomy of the Kozak Hetmanate, which was divided between the Russian Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Later, the Russian Empire would occupy Crimea, and although Ukrainians continued to colonize Crimea and the Donbas, Russians were settling alongside.

In this way, the terrain still plays a role in provoking regional conflict. However, the difference today is that Ukrainians have a chance to consolidate all their territories for the first time in centuries — independent of enemy threat from the north coast of the Black Sea. In that way, the Gates of Europe can be further strengthened.

The separation between Western and Eastern Christianity became especially important in the 16th century, when the largest area of Ukraine was controlled by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Within the united entity, numerous churches had to coexist: the Polish Catholic Church; the U krainian and, later, Russian Orthodox Church, which themselves existed parallel to the Greek Catholic Church; as well as a number of protestant churches.

During the 16th to 17th centuries, the divide between the two main churches — Catholic and Orthodox —created a space for learned discussion, albeit dogmatic. At the same time, the contentious dialogue was good groundwork for intellectual diversity. In the domain of religious tolerance, Ukraine was ahead of Europe in that period. This was true up to the bloody war of 1648 which deepened divisions and embittered the churches to one other.

Having extended as far as the Dnipro in the 17th century, the western boundary of the churches moved back to Galicia in western Ukraine, roughly following the borderline between the Austrian and Russian empires prior to the First World War.

In that way, Ukraine was divided between the purely European and Catholic Austrian Empire, and the Orthodox Russian Empire. Including the latter within the European context was largely disputed within groups of intellectuals of the 18th and 19th centuries. These groups included Russians who themselves regularly emphasized the distinctiveness of Russia. Thus, Ukraine once again became a gateway between Europe and the Russian “unique way.”

Ukraine-Rus and Muscovites

If Ukraine is the gateway to Europe, then what is Russia? This is a tricky question. On the one hand, European history cannot be considered without including Russia. On the other hand, Russia was always different and hardily proclaimed — and still proclaims — its difference.

In this matter, Serhii Plokhii refers to Larry Wolff, a historian specializing in the history of Eastern Europe. Wolff points out that Russia has made overtures to Europe at certain times in its history, but isolated itself entirely at other times — positioning itself as having interest and influence in Europe, yet setting itself apart.

Russian-Ukrainian relations are dominated by the struggle for the metaphorical keys of Kyiv

If Kyiv and Ukraine are indeed the Gates of Europe, then the challenge for the keys of the gates is not only crucial for Ukraine, but affects the whole of Europe as well. A poignant example is the period after the Second World War, when Russia (then, the Soviet Union) occupied all of Ukraine, and Europe could not stand against Russia without foreign support from the United States.

The struggle between Ukraine and Russia for Kyiv reaches back to the 12th century, when the northern and southern kings of the Rus fought for prominence. The battle for the legacy of ancient Rus continued into the 18th century.

After the victory in the Great Northern War in 1721, Tsar Peter the Great declared himself Emperor of a Russian — not Muscovite — Empire. The name Russian was derived from Rusyny. In this manner, Russia fashioned a closer association to the Ancient Rus. Later, to differentiate themselves from Russians, Ukrainians started to refer to themselves only as Ukrainians, and the distinction between Rusyny and Russians blurred, in favour of Russia’s interpretation.

- Read also: Rename Russia “Muscovy,” some Ukrainians say

Ukrainian and Russian historians have been clashing over the heritage of Kyivan Rus for centuries, even contesting the skeletal remains of the Rus king Yaroslav the Wise. Yaroslav is depicted on the banknotes of Russia and Ukraine, and is claimed to be one of the most famous historical figures both by Russians and Ukrainians. To protect the Ukrainian claim to Yaroslav, in 1943, when the Soviet army was descending upon Kyiv, Ukrainian activists transported Yaroslav’s remains to the United States so that the Russians could not abscond with them to Moscow.

The legacy of Yaroslav is pivotal. His death marked the end of an important period in the history of Kyivan Rus — the period of its consolidation. Next, came an era in which the state closely followed the path of the Carolingian Empire in the middle ages. After the Carolingian collapse, the empire split into several smaller states, with similar long-term consequences to those which impacted Rus — the formation of two adversarial states. They eventually evolved, respectively, into France and Germany, and Ukraine and Russia.

The historical battle for the Rus legacy and for the Gates of Europe, although rooted in the past, remains firmly in the present. Whenever Russian President Putin claims that Russians and Ukrainians are one and the same people, he distorts history and subsumes Ukraine into Russia. This was his oft-repeated rationale more than a year before the annexation of Crimea. He openly made the statement in a speech delivered on 18 March 2015, on the first anniversary of the annexation of Crimea.

In the end, the question of boundaries and frontiers remains vital, not only for Ukraine and Europe, but in relation to Russia’s claim over the Donbas.

Russian mercenaries and volunteers came to the Donbas, ostensibly to protect the values of the "Russian world" from the “attacks of the West.” In this context, they sought to portray Ukraine as a battleground between decadent Western attitudes and purist Russian beliefs.

Russia continues to promulgate its propaganda that the West tries to warp the minds of Ukrainians, while Russia purports to use warfare to convey the truth. Such Russian “enlightenment” goes against all definitions of human rights.

The political difference between the two countries has been evident on many occasions. In 1993, then Russian President Yeltsin shelled the Russian Parliament to resolve a power struggle, while Ukrainians conducted their inaugural transfer of power, from the first president and parliament to the second, peacefully, without a drop of blood. The war in the east is more than just a conflict between two states, it represents a clash of values — if not civilizations. Ultimately, it is a continuation of historical conflicts, only too familiar to a frontier country like Ukraine.

Real also:

- Evil empire revives in Putin’s regime and FSB methods of “fighting terrorism”

- The mystery of how Kyivan Rus shaped early Christianity in Norway

- Anna of Kyiv, the French Queen from Kyivan Rus

- Ukrainian conflict is between ‘heirs of Kyivan Rus’ and ‘heirs of Golden Horde’