Why is the West reluctant to set up Ukraine for victory and restoration of the internationally recognized borders from 1991?

The US has repeatedly stressed that it will help “Ukraine succeed on the battlefield so that they can succeed at the negotiating table” or “the war will end at the negotiating table.” “You remind us that freedom is priceless; it’s worth fighting for for as long as it takes. And that’s how long we’re going to be with you, Mr. President: for as long as it takes,” President Biden said. All the way to the negotiation table.

Gen Ben Hodges, former Commanding General of the US Army in Europe, has argued that “to support as long as you need” does not mean “to help to win the battle.”

On 29 January, the Institute for the Study of War pointed out that the patterns of Western aid – slow and incremental – and its refusal to supply Ukraine with higher-end weapons systems have shaped Ukraine’s ability to develop and execute sound campaign plans. It has limited Ukraine’s ability to initiate and continue large-scale counter-offensive operations.

Western weapon delays may have cost Ukraine its winter counteroffensive – ISW

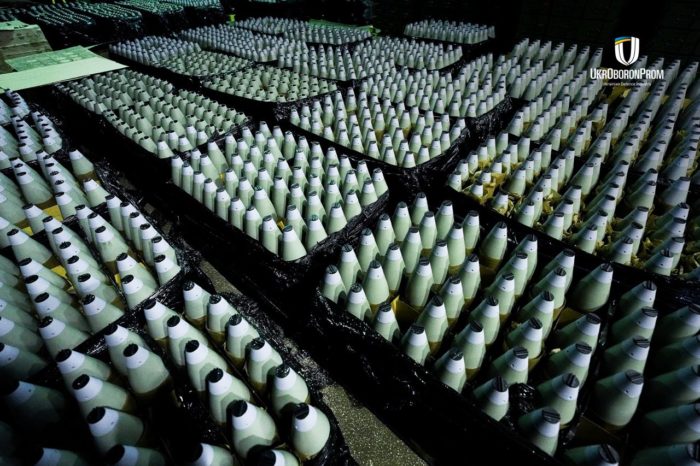

The EU has promised Ukraine 1 million rounds of artillery ammunition within one year, both from the member states own stockpiles as well as from the framework of joint purchases. Deliveries from their stockpiles are reportedly slowing down and the member states are yet – one month later – to reach an agreement on the framework for the process.

Even the Pentagon leaks support the assessment. The supplies fall short of what even American military planners have assessed that Ukraine needs to make the most of the expected offensive.

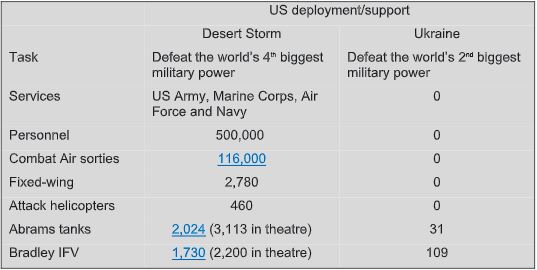

I have previously used Operation Desert Storm (1991) as a point of reference to help illustrate the gap between what is needed and what is provided (by the US).

For comparison: In 1991, the US and its international partners deployed knowing that they would not be fighting alongside Kuwait forces. Ukraine, in contrast, has a professional and motivated Armed Force. Like Iraq, it is, however, equipped with Soviet-legacy aircraft, tanks, infantry vehicles, artillery, and MLRS. A Western coalition of the willing would, therefore, need to deploy fewer forces than to Kuwait.

But still, the gap is telling. President Zelensky has stressed that Ukraine can’t start a counter-offensive yet due to a shortage of weapons, including heavy equipment and fighter jets.

The United States has a crucial role in ensuring Ukraine’s victory

How difficult is it to simply state that we support President Zelensky’s vision of victory? Or to tell Russia in no uncertain terms that we will uphold and increase the support for Ukraine until Russian forces are evicted and territorial integrity has been restored? That we will do what is needed to win.

It is apparently difficult. Very difficult.

The bipartisan draft resolution of the US House of Representatives “On the Position of the House of Representatives on the Conditions for Ukraine’s Victory” is in this context, a crucially important step. If passed, a commitment to a Ukrainian victory and restoration of its internationally recognised borders of 1991 will trigger the crucial question: How?

After having grappled with the question “Why is the West not setting Ukraine up for victory” for the last nine years, I ended up focusing my attention on the US. Not because it carries a bigger responsibility to support Ukraine than its allies in Europe. It does not. They share responsibility because our collective security and stability are impaired. Russia is waging a hybrid war against the West. It is our war to fight, and we should fight it alongside Ukraine.

I focus on the US because it has taken security and defense seriously when Europe has not. The US is the only party with the actual capability to profoundly change the military balance on the battlefield. Additionally, the US is leading the “pack” of willing (and not so willing) Western countries.

Europe has failed to invest in security and defence, making itself fully dependent on the US. It has no strategic autonomy within security and defence and is, consequentially, unable to provide the military support needed for Ukraine to defeat Russia.

Europe has the power to respond, but not impose its will.

Europe not only lacks the military capability to intervene independently but also lacks leadership and a shared vision. Germany and France have for years led an attempt to appease an increasingly more aggressive Russia and “crashed and burned” in the process. Additionally, after years of underfunding and reductions, Germany lacks a credible fighting force and the military power to lead Europe in a time of crisis. The trust deficit between Germany and France and many of their European partners remains huge as the balance of power in Europe is shifting eastwards.

Lastly, NATO has proven itself unable to respond to the war in Europe. The fact that the “Ukraine Defence Contact Group” exists at all is evidence of its failure. For an Alliance designed to stop conflicts threatening its member states, coordination of the defence aid should have been an integrated part of its tasks. It is not. On the contrary, NATO has limited itself to non-military support only. The Alliance is highly divided and has stepped back from its past commitment raising concerns over its future relevance.

Why the West is not setting Ukraine up for victory

After consulting with several internationally renowned experts, I have come up with some possible answers. I asked them the following questions: Do you agree that the West does not set up Ukraine for victory? If yes, why is that? If not, what is the strategy?

All shared my assessment that the West is not setting up Ukraine for victory, rendering the last question redundant. They offered, however, an intriguing insight into the “why” part.

1. Firstly, it’s a result of flawed institutional thinking.

The mentality and mindset of politicians, officials, and officers alike – are shaped over decades, not months or years. After more than 30 years of “peace in our time,” globalization, increased trade and transparency, and the hope for increased cooperation with a “democratic leaning” Russia, Western long-term foreign policy is not easily disrupted. Foreign policy and threat assessments are institutionalized and not necessarily influenced by crisis or war. Especially when strategic thinking has been partly influenced and shaped by the aggressor. More of that later.

Imagine trying to convince a conservative to turn liberal or a right-wing to become left-wing. Fundamentally changing the strategic thinking of a country or an Alliance is an equally daunting task.

The idea of “containment”, an outcome that can be “managed”, and a return to past diplomatic relationships and economic cooperation endures despite evidence of the contrary. It is human nature to wish for the tried and familiar, including the “daily routine” of international relations. Or “Peace in our times.”

“Perhaps they will rise to the occasion. I wager the chances are 50%. But on present form, they are preparing the ground for an outcome that they will not be able to manage at all”, James Sherr says.

2. Secondly, it is a result of ignorance.

Russia’s nature as an imperial power should be incontrovertible. It has grown continuously for centuries at the cost of its neighbours. It has not only avoided the disintegration that occurred in other empires, such as the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary but has also avoided the era of decolonization like the French and British empires. On the contrary, even as the Soviet Union was being dissolved, Russia set about re-establishing its control over the post-Soviet space. Its calls for a sphere of interest and the right to veto the decision of independent and sovereign countries are only a continuation of its past and present nature.

Neither its imperialistic history nor its continuation in its present foreign policy has, however, been reflected in Western academic studies of Russia.

In the FP article “It’s high time to decolonize Western Russia studies,” Artem Shaipov and Yuliia Shaipova, argue that “today’s Russia studies in the West still replicate the worldview of an oppressor state that has never examined its history and is nowhere near having a debate about its imperial nature at all—not even among the Russian intellectuals or so-called liberals with whom Western students, academics, and analysts generally interact and cooperate.”

Russian, East European, and Eurasian studies are too often studied as one region centered on Russia compared to studies of individual countries. Their uniqueness disappears in Russian disinformation.

The very same academic institutions that produce the experts, analysts and officials to Western public institutions and think tanks – including ministries, armed forces, and intelligence agencies – have not only perceived Ukraine (and Eastern Europe) through the lens of Russian imperial thinking but also actively promoted it.

Western knowledge of Russian and Ukrainian history, culture, and language is flawed. It is based on the (dis)information Russia has sown for decades.

The West is just now slowly waking up to the fact that it’s a vibrant, innovative, and at times more democratically aware than most of Western Europe. In 2014 – two decades after the wall’s fall – NATO had minimal institutional knowledge and expertise on Russia. It had close to no insight into Ukraine. I know because I used its rush to re-establish the expertise to prepare for my posting as a defense attaché in Ukraine.

The Ukraine many have come to know after 24 February 2022 is the Ukraine I came to know eight years earlier.

It is time to acknowledge that Ukraine will strengthen the EU and NATO, not weaken them. Today, the EU and NATO are reduced by the countries focusing on appeasing Russia while refusing to invest in security and defence.

Still, the institutional reluctance to accept new knowledge persists. It is even harder to accept one’s own fundamental flaws.

3. Thirdly, it’s a result of the Hybrid War.

The main battlespace occurs inside the cognitive spaces of populations and key decision- and policymakers. It aims to confuse and manipulate. Using disinformation, cyber-attacks, blackmail, provocations, fabrications, military deceptions, and other active measures, it creates a virtual reality that prompts its victims into making the political decisions Russia wants without suspecting (or acknowledging) they are being manipulated.

In 2016, the European Parliament acknowledged that Russia was

“…aggressively employing a wide range of tools and instruments, such as think tanks and special foundations, … multilingual TV stations, pseudo-news agencies, and multimedia services, … religious groups, …social media and internet trolls to challenge democratic values, divide Europe, gather domestic support and create the perception of failed states in the EU’s eastern neighborhood.”

The European Parliament stressed that Russia was funding political parties and other organizations to undermine the EU. Kremlin propaganda directly targeted specific journalists, politicians, and individuals in the EU.

Politicians, experts, analysts, academics, think tanks, non-governmental organizations, and more, have been actively targeted and at times, infiltrated, to help manipulate the foreign policy of both the US and European countries to its advantage.

4. Fourthly, it’s a result of fear (both real and imaginary).

The West fears chaos and uncertainty. How does the world look like if Russia – the world’s biggest nuclear power – is defeated?

There seems to be a consensus that a Russian defeat in Ukraine means the end of Putin’s regime. Few analysts, however, are expecting Russia to emerge as a democratic country in the aftermath of the defeat. Quite the opposite, the potential scenarios range from a radicalisation of its current form (“North Korea scenario”) to a collapse and disintegration altogether (“Somalia scenario”).

Europe and the US also fear the risk of escalation, world war, and a nuclear confrontation. While the strategic messaging from Heads of States conveys their concerns, it is hard to differentiate between what is genuine fear and what is an excuse for own strategic shortcomings.

On the one hand, the war has de facto escalated since 2014, and Russia is controlling the escalation according to its strategic aim and objectives. The war has always been a part of a broader confrontation between Russia and the West. Moreover, both the West and Ukraine have repeatedly crossed Russia’s red lines without triggering WW3.

On the other hand, the West has proven itself utterly unprepared for a conventional, protracted, and brutal war in Europe. It is running out of weapons it can supply Ukraine. Its stockpiles of weapons, ammunition, and spare parts are running low. The defense industries are still not anywhere close to where they need to be to meet the urgent needs for military equipment.

Additionally, the lack of public discussion about Western “boots on the ground” in Ukraine – an alternative to the present strategy and according to its late strategic concept and the UN Responsible to Protect doctrine – immediately became a “black or white”, “on/off” debate due to the strategic messaging by the Heads of States. They have themselves induced fears by creating the idea that if the Alliance intervenes, the war will escalate into a broader confrontation (which it always was). The risk of a nuclear confrontation and World War 3 has been a part of their messaging throughout.

Stratcom does not make it true. More importantly, it has been repeatedly refuted by events on the ground. Both the West and Ukraine have repeatedly crossed the red line without triggering anything but belligerent, irresponsible diplomatic noise.

States of Heads have, therefore, more than one reason to demonstrate restraint. It is either a result of real felt fear, inability to act upon the present threat, flawed institutional thinking, ignorance or a result of manipulation. Or a combination of all of the above.

Either way – and in the words of James Sherr,

“all of the fears continue to be intellectualized despite scant evidentiary foundation (and much evidentiary basis to the contrary). But intellectuality is mainly a disguise for other things: fear of the unknown and laziness – the fear of having to rethink and redo everything. Now, as in the past, the present custodians in Washington are temperamentally unable to seize the moment, to employ the means prerequisite to the goals they claim to support. What they actually want is stability. That means there must be a world with Russia: to be ‘managed,’ to be ‘contained’ where necessary, but always with the ’strategic’ objective of long-term reconciliation and compromise.”

Politicians will always choose certainty over uncertainty. The present aggressive and authoritarian – but predictable — Russia might be seen as preferable to an unpredictable “North Korea” or “Somalia“ version. Fear of a Russian defeat might, therefore, be dampening Western commitment to a Ukrainian victory.

5. Fifthly, it’s a result of the need for public support.

Twenty years ago – on 19 March 2003 – the US launched a major military invasion of Iraq. It was the start of an eight-year conflict that resulted in the deaths of more than 4,000 US soldiers. It demonstrated American military might, achieving its primary objective of ousting the regime of dictator Saddam Hussein within weeks.

However, despite its initial success and the “shock and awe” the military campaign ended up deeply dividing Americans and alienating key US allies. Looking back, 62% of Americans concluded that it was not worth fighting for. Majorities of military veterans, including those who served in Iraq or Afghanistan, came to the same conclusion.

Decades of military operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan (limiting the list to NATO), with various degrees of success and some at high human and economic costs, public support for new military “endeavours” are limited. As a result, only 16% of Americans favour increasing the US troop deployments overseas, versus 40% who want to decrease deployments. Only 48% of Americans have great trust and confidence in the military and only 52% say the military’s ability to win a potential future war decreased their confidence.

According to Morning Consult’s US Foreign Policy Tracker Index from January of 2023, nearly 40% of US voters favor isolationism, while 30% want stability, and only 17% want engagement. Neither side wants the US to be the world’s police.

That’s hardly a surprise, knowing that it took several years to get the US involved in the world wars of the 20th century. It was hoping arms supplies alone would suffice to counter two wars with global ramifications. The US joined the fight only after being attacked by Japan in 1941 and after Nazi Germany and Italy declared war on the US.

The strategy was then and still is, fatally flawed.

That said, American support for Ukraine remains solid. Nearly three-quarters support upholding economic and military aid, and 58% are willing to continue to support the country “as long as it takes,” even if this means higher prices for gas and food in the US. Sending troops to help Ukraine defend itself against Russia, however, is “only” supported by 38% of American voters.

According to PEW research,

“The Iraq War has a long and complicated legacy. After the war officially ended, it remained an issue, to varying degrees, in both the 2012 and 2016 presidential election campaigns. Even in the 2020 campaign, nearly a decade after the war’s end, Trump and Joe Biden each portrayed themselves as better able to extricate the nation from what have been called ‘endless wars’ – the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

As the presidential election is fast approaching and after having just withdrawn from an “endless” and unsuccessful war in Afghanistan, the Biden administration knows deploying troops to Ukraine will not be popular. Especially knowing that the US – both historically and presently – prefers isolation, opposes US role as the world’s police, does not list US/China relations (27%), Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (24%), or upholding democracy globally (14%) among their five top foreign policy concerns.

The sad fact is that none of us – neither the West nor Russia – are that good at winning wars.

6. Lastly, it’s a result of strategic deliberations.

As the Russian Federation is aiming for a protracted war (with huge global ramifications), the US will be considering its ability to “manage” both Russia and China as it risks being drawn into another “endless war.” Unfortunately, it might end up managing neither.

Unfortunately, Europe has been demonstrating disinterest in security and defense policy and, consequently, the integrity of NATO. Nine years after the war started, it is still not prioritized by many European countries. That’s reflected in the fact that only 7 out of 31 member states met their obligation to invest 2% of GDP in defence in 2022. Knowing that decades of underfunding, cutbacks, public disinterest, and political neglect have resulted in huge capability gaps across European armed forces, even the fulfillment of the pledge of 2% would not suffice to rebuild European military power anytime soon.

The US is leading an alliance with all signs of internal discord and a lack of commitment to European security and stability. This will add to the dilemmas the Biden administration is facing while grappling with the Russian hybrid war, its blatant confrontation with the West and the war in Ukraine. And China.

In this context, a stalemate might be seen as the lesser of two evils. It does not require a change in strategy or involve any political risks. The West only needs to continue doing what it is already doing.

Unfortunately, a stalemate is based on the illusion that Russia, at one stage, will be forced to give up.

However, it will result in the exact opposite: a reduction in Western support for Ukraine, the continuation of the war, and the very real risk of a future Russian victory.

It would be the same “stalemate” the West accepted in 2014-2022. A stalemate that allowed Russia to prepare for a full-scale invasion. There is no need to repeat the same mistake twice.

There are many other strategic deliberations, I am sure.

- Do they believe that a decisive Ukrainian victory is unachievable?

- Are the slow and incremental delivery of weapons a way to manage expectations?

- Is the US using the opportunity to force Europe to step up to its obligations and invest in security and defense?

- Is it an opportunity to promote US defense industries?

- Has the war turned into an opportunity to reduce Russia’s conventional military power?

- Is the US concerned about Ukrainian EU membership and the consequences of an EU with (potentially) a higher degree of strategic autonomy?

- Are France and Germany concerned about their level of influence if Ukraine is integrated as the balance of power is shifting eastwards?

They might even still have the naive idea that Putin will come to the negotiating table and peace (or the absence of war) is possible without a Russian defeat.

I am sure the list is much longer. I am equally sure I don’t have the answers to these questions.

I am, however, rather convinced that the deliberations – or strategic thinking – will be influenced by a mix of flawed institutional thinking, ignorance of both Russia and Ukraine, Russian disinformation, and Russian-induced fear, as well as concerns over public support and strategic considerations beyond Ukraine.

This is also the main reason why the West is reluctant to set up Ukraine for victory. A series of institutionalized flaws and a lack of strategic thinking.

Because of the dramatic and far-reaching consequences of a Ukrainian defeat – since anything but a full restoration of its borders from 1991 means that the war will continue until Ukraine is defeated — I find it immensely easier to explain why we should do what is needed for Ukraine to win than to explain why we aren’t.

Russia has been expanding for centuries and will continue to expand as long as the West allows it to continue its Western expansion at the cost of its neighbors, international law, peace, and stability. It is in its imperialistic nature.

To start having a grown-up discussion about what is needed for Ukraine to win, the West needs to:

- Articulate the potential consequences of its demise. That will help motivate a shift in policy.

- The NATO countries also need to provide military – not political – advice on how to conduct a military intervention in Ukraine according to NATO’s past commitments and the UN Charter. This will provide a better basis for discussing Ukraine’s military requirements.

- Lastly, the West needs to do what it has asked Ukraine to do: Reform its institutions of power and the education system producing the politicians, experts and analysts for the structure.