Foreign military aid to Ukraine has been a crucial asset for Kyiv's war effort. The Kremlin is well aware of its importance and targets Ukraine's partner countries with propaganda and disinformation campaigns.

A widely used strategy is to portray pro-Ukrainian governments as warmongers that prolong the conflict through military supplies and, given a chance, would drag their countries into a full-scale war with Russia.

The path to peace supposedly lies in some kind of compromise with Moscow or outright capitulation to Russia’s demands. Pro-Russian actors thus hijack the discourse by claiming for themselves the title of peacemakers while pushing Ukraine supporters into the rhetorical defensive.

This narrative stands on clay feet for several reasons:

- In all aspects, Russia was the aggressor. The Kremlin did not even try to construct any "Gliwice-like" incident to justify the invasion of a sovereign country.

- By supplying weapons to Ukraine, NATO countries can prevent further Russian aggression and thus keep war away from their own borders.

- If Ukraine surrenders, this will not stop the violence. The acts of the Russian military on the occupied territories, including murder, torture, and rape of civilians, have already proven that.

- According to the UN Charter, supplying weapons to a country under attack is an acceptable means of achieving peace, unlike Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which is a clear violation of the UN Charter and illegal according to international law.

Nevertheless, the "peace vs. war" narrative remains a popular tool for pro-Russian actors abroad.

Peace vs. War narrative in the Czech Republic

Most recently, such methods have been used in the Czech Republic, one of the most active supporters of Ukraine by military and humanitarian aid. Pro-Kremlin narratives, spread not only by pro-Russian actors but also by local populist politicians, made their mark in Czechia's presidential elections.

The race for the Czech Republic's "top job" came down to a duel between the retired general Petr Pavel and the populist billionaire Andrej Babiš, who previously served as the country's prime minister. Pavel -- who, in the end, scored a landslide win on January 28 -- was a clear favorite according to opinion polls. This might have inspired his opponent to try rather aggressive campaign methods.

Babiš might not be ranked among the most overtly pro-Russian figures in the Czech public sphere. While he was in office as prime minister, Prague expelled dozens of Russian diplomats after the revelation that Russian operatives were involved in the deadly munitions explosion in the Czech town Vrbětice.

However, Babiš is no stranger to "borrowing" pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian narratives for his own political goals. The populist leader repeatedly attacked the incumbent Czech cabinet for providing too much aid to Ukrainian refugees while "neglecting" its own citizens.

Therefore, the "peace vs. war" narrative was a suitable and readily available choice for Babiš to use against Pavel. The retired general indeed represented an ideal target. He is a former NATO Military Committee chief, supports Czech weapons supplies for Ukraine, and received endorsement from the incumbent, pro-Ukrainian Czech cabinet.

Babiš's campaign relied heavily on associating his rival with war and portraying him as a militant hawk. In reality, Pavel never stated an intent to send Czech troops to war against Russia, nor could he do that from the position of a head of state. Czechia is a parliamentary republic where the president has a mostly ceremonial role and does not have the legal power to declare war.

Nevertheless, billboards with this message sprung up around the country: Pavel will drag his homeland into the war in Ukraine, while Babiš is a diplomat who will strive for peace.

The same message began to circulate on Czech disinformation outlets and through chain emails:

"Ukraine has enough weapons, but cannot win due to Russia's quantitative advantage… We are at war, it is the duty of every capable man or woman to defend the free world from the aggressor,"

claims an author of one such fake email, signing himself as General Pavel.

A pro-Russian Telegram channel neČT24 - suspected of connections to the propaganda outlet Sputnik - published a doctored video where Pavel seems to express a desire for war with Russia, while in the original, he says the exact opposite. According to Czech disinformation experts, the video has likely reached hundreds of thousands of viewers.

Protests against supporting Ukraine under the auspices of peace are not, however, limited to the presidential elections.

The right-wing populist Freedom and Direct Democracy party (SPD) regularly speaks out against sending weapons to Ukraine and demands pressure on Ukraine to "end hostilities." SPD's own presidential candidate Jaroslav Bašta, who came in fifth with 4.45%, also presented himself as the candidate for peace.

The same stances can be heard from the other end of the political spectrum, for example, from among Czech communists.

Also in the spirit of the horseshoe theory, the so-called "Peace and Justice" petition from this year's January attracted signatories from the Left and the Right. While this initiative acknowledges Russia's blame for the war, it also accuses the West of perpetuating the conflict through arms supplies and sanctions.

The petition's goal, as its name suggests, is peace, but one involving compromise between "all involved parties." The authors mock the argument that "Russia should just withdraw from Ukraine" as unrealistic daydreaming. At the same time, they do not offer any actual, workable alternative. In fact, they state they do not know what form this peace should take or how it should be reached as long as it is "just."

Czechia is certainly not the first or the last target of this narrative, as apparent in the nearest neighborhood.

In Slovakia, a disinformation website Bádateľ spread a false claim that the Slovak government is planning a general mobilization for war against Russia, adding that such a process is already underway in neighboring Poland. Neither of the statements was true - the outlet simply used a regular Slovak military exercise to spread fear of the war.

Slovakia is an important battlefield of Russia's hybrid war, as its government is considering supplying its MiG-29 jet fighters to Ukraine. However, the incumbent cabinet has lost a vote of confidence, and the country expects new elections this fall.

According to the polls, Robert Fico's Smer (Direction) is the second strongest contender, which spells trouble for the Bratislava-Kyiv relationship. Fico, who openly propagates pro-Russian views, voiced opposition to sending arms to Ukraine as they would "bring nothing more than hundreds of thousands of dead."

His victory in the elections would likely put a stop to the jet transfer or to any other kind of military support.

Pro-Russian groups in Germany, comprising both native Germans and the Russian diaspora, also like to operate with "anti-war" and "pro-peace" slogans. The German Communist Party held a "peace and solidarity" festival, which included a panel discussion called "Peace with Russia", spreading anti-Ukrainian messages and hosting an ex-GRU Oleg Yeremenko as a speaker.

In Hungary, this narrative comes from within the pro-government circles rather than fringe or opposition groups. During the last year's parliamentary elections, Orbán's campaign heavily exploited the "Ukraine card": while portraying his Fidesz party as the only guarantee of peace for Hungarians, the incumbent PM accused his political opponents of dragging the country into war.

A headline by the pro-government outlet Magyar Nemzet, published shortly before the vote, well summarized the Orbanist position: "The Left prepares for tomorrow's election with a pro-war demonstration."

Magyar Nemzet was, of course, talking about a demonstration in support of Ukraine.

False peace

Portraying Ukraine or the West as the aggressors in the ongoing conflict relies on rhetorical sophistry and gaslighting. By disassociating itself from the term "war," the Kremlin hopes to set its own rules for the conversation.

That is one of the reasons why Russia calls its invasion a "special military operation," while NATO is accused of waging "war" simply by providing materiel and diplomatic support to Ukraine. This follows an old pattern of denying any involvement in military aggression despite ample evidence, such as the occupation of Crimea or the war in Donbas.

Even shortly before the full-scale assault on Ukraine, Putin's spokesman Peskov stated that "Russia, throughout its history, has never attacked anybody," ignoring past invasions of Georgia, Chechnya, Afghanistan, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and much more.

Pro-Russian actors like to repeat this narrative and whitewash all cases of Russian aggression, portraying them as, for example, self-defense or safeguarding local minorities from nationalist governments.

This way, Russian propaganda can shift the focus towards examples of military aggression by its rivals, be they real, such as the US-led invasion of Iraq, or imagined, like the supposedly planned NATO invasion of Russia through Ukraine.

No amount of rhetorical gymnastics or whataboutism can, however, undo the fact that Russia invaded a sovereign state and is thus the only initiator of the Russo-Ukrainian War. In the past article, we have already examined the arguments that attempt to shift the blame for the conflict on Kyiv or the West.

"Peace" is also the common argument for seeking compromise with Russia, and not only among openly pro-Russian actors. Even perhaps honest-minded individuals demand that military aid be replaced by diplomatic efforts to bring both sides to the table and end the suffering of civilians.

Unless the peace terms involve a complete withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukraine, evidence shows this would not bring an end to violence against the Ukrainian population.

The Russian occupying forces committed murder, torture, and rape of civilians, in what the Human Rights Watch called a "litany of violations."

This was not by far limited to contested areas at the front. Some of the worst war crimes took place in areas at the time completely under Russian control, such as the massacres in Bucha or Irpin.

Furthermore, these are not simply ad hoc acts by combatants, "explainable" as common collateral damage of an armed conflict. Anti-Ukrainian chauvinism has been promoted in the Russian public sphere for years, and ethnic-based violence is constantly encouraged by the Russian media.

The examples are too numerous the count, although some are worth highlighting. For example, the state-controlled RIA Novosti published an article in April 2022 calling for the destruction of Ukrainian statehood and identity. The Russia Today propagandist Anton Krasovsky played on a similar genocidal note last October when he encouraged the killings of Ukrainian infants.

How Russia justifies the murder of Ukrainians: Russia’s 2022 “genocide handbook” deconstructed

Oftentimes, war crimes against civilians are systematic and organized by the Russian leadership. Activists and public figures are targeted, kidnapped, tortured, and killed. Even before the invasion began, the United States published a Russian hitlist of influential Ukrainians that were to be arrested or killed.

The Russian government also organized and financed torture chambers in the occupied territories, as evidenced by a joint team of international and Ukrainian investigators.

If Europeans do not wish for the war and violence to spread further, the best way to ensure it is by arming the Ukrainian military. It is quite telling that some of the NATO countries closest to Russia geographically -- Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia -- donate the largest share of their GDP to Ukraine's war effort. Their leadership realizes this is currently the best way to keep the enemy away from their own borders.

Putin's defeat would not only put a strong Ukrainian bulwark between Russia and other European countries, but the cost of failure could, by itself, deter future aggression.

Finally, supporting a country under assault through military supplies is a fully legitimate action according to the United Nations Charter:

"We also intend to commit ourselves, as necessary and appropriate, to helping States build capacity to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity and to assisting those which are under stress before crises and conflicts break out."

This certainly applies to Ukraine, given the widespread evidence of Russian war crimes. Several governments and scholars agree that the scale of the crimes, together with clear intent, constitutes genocide against the Ukrainian nation.

Russia's invasion, on the other hand, is in a clear violation of the Charter:

"All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations."

The UN Secretary-General António Guterres cited this very paragraph when denouncing Russia's aggression. Supporting Ukraine's war effort is therefore not only in the interest of its partner countries but also in line with international law.

Soviet roots

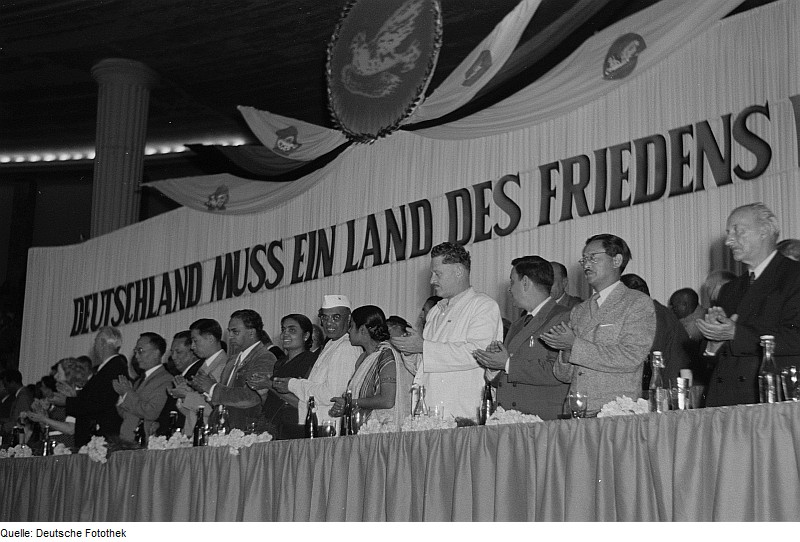

Like so many current pro-Russian narratives, even this one is simply a dusted-off version of Soviet propaganda.

In posters and slogans, "peace" was presented as one of the most important guarantees of the socialist system; only through solidarity of the Eastern Bloc countries were the capitalist aggressors kept at bay. "Peace" was thus used to justify the massive standing armies and the imposing arms industry of the Soviet Union and its satellites.

The dichotomy of the aggressive, capitalist West and peaceful, socialist East was not aimed only at the domestic audience.

Through both public and clandestine means, Moscow controlled or supported various international peace movements with the purpose of discrediting the United States and other "imperialist" powers.

A US report from 1982 called it Moscow's "peace offensive." Through spies, journalists, and diplomatic corps, the Kremlin supported a colorful assemblage of anti-war movements abroad, mainly in the West. This included various grassroots groups, local communist parties, and even religious organizations. Of particular interest were organizations aimed against Western nuclear arms development.

In 1948, Cominform - a coordination body for the Eastern Bloc's communist parties - established the so-called World Peace Council (WPC). Its declared goal was to unify influential voices across the world, such as artists, intellectuals, scientists, and politicians, in joint efforts for disarmament and peace and against war and imperialism.

As the last stated goal suggests, WPC was very much a soft power tool against the West. Just like other Soviet-backed peace initiatives, the Council criticized Western nuclear arms while avoiding the topic of Soviet weaponry.

The same went for military interventions. For example, in 1956, WPC denounced the British-French-Israeli involvement in the Suez Crisis, while omitting the Soviet invasion of Hungary in that very year.

The Council attracted a number of well-known figures, including Jean-Paul Sartre, Pablo Neruda, and Pablo Picasso.

In the long run, however, WPC did not achieve significant success, as it lost appeal for people not directly working for Moscow. After failed attempts at denouncing the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and Afghanistan, many non-communist members began to realize the Council is simply an appendage of the Kremlin and parted their ways with the organization.

The Soviet "peace offensive" may not have been successful in the end, but that does not preclude the current regime in Moscow from repeating the strategy. Just like then, it also relies on either ignoring or whitewashing Russian military interventions while shifting the debate to real and imagined transgressions of Russia's rivals, branding them as warmongers.

Related:

- Why Jordan Peterson is wrong about Ukraine

- Russian propaganda in war: fake “fact-checkers,” far-right conspiracies, and distracted progressives

- How Russia justifies the murder of Ukrainians: Russia’s 2022 “genocide handbook” deconstructed