On 17 October 2022, Lyudmila Huseynova and Anna Olsen were swapped together with 108 women as part of the so-called women’s exchange.

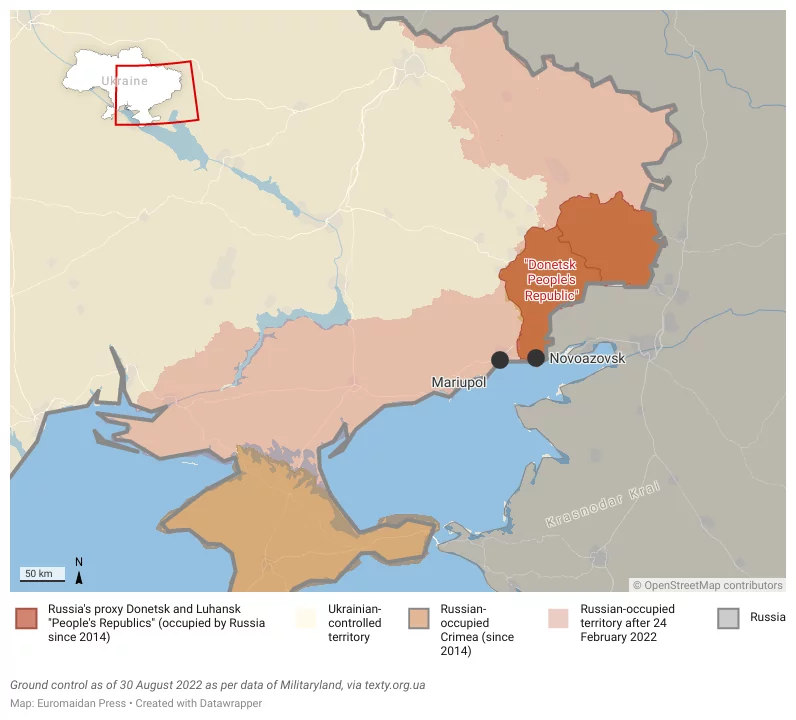

In 2019, while delivering humanitarian aid to orphans, volunteer Liudmyla Huseinova was captured in Russian-occupied Novoazovsk. She spent three years and 13 days in captivity. Anna Olsen is a combat medic. On 12 April, Russian forces captured her at the Mariupol Azovmash plant. She spent 189 days in captivity.

Liudmyla Huseinova never engaged in combat because she had always believed war was evil. Since 2014, she has lived in Novoazovsk, Donetsk Oblast. She helped orphaned children after Russia’s occupation of Donbas in 2014 until she was arrested in 2019 on formal charges of “espionage,” with the real reason, however, being closer to her unwavering support for Ukraine.

Anna Olsen is a senior combat medic of a chemical defense company in a separate marine brigade. She joined the army at the age of 19 in 2015.

“Despite ending up imprisoned, I never once regretted my choice,” she shares.

Anna does not give television interviews or take photos. Her child remains in the occupied territory.

Russian forces captured Anna on 12 April at the Azovmash plant, one of the strongholds of Ukrainian forces in the seaside city of Mariupol, besieged on all sides by the invading Russian Army.

“We surrendered because it was the only way to survive,” she told.

She was initially held in various prisons on the territory of the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic” (DNR). After that, she was transported to Russia, where she had also been moved around.

Highly traumatic experience

In captivity, Liudmyla and Anna were subjected to physical and psychological violence.

Liudmyla recalls spending more time in prison with non-political female prisoners.

“I remember being taken to the pre-trial detention center. When they opened the cell door, there were 20 women inside. Only one of them was politically active. She was in a tough emotional and psychological state. She stayed under the blanket all day, rising only at night to drink tea and eat a slice of bread. The remaining women had a criminal history, serving sentences for drugs and murder.”

Anna claims that the so-called DNR supervisors treated her more humanely than those in Russia.

“Once we arrived in Russia, we realized the difference immediately. Since the first minutes, the women were treated much more harshly. We entered Russia from the occupied [DNR] territory with our hands untied and our eyes open, and we could smoke calmly and talk. As soon as we entered Russia, they tied our hands behind our backs, bent us down so my forehead almost reached my knees, and led us away. “

According to Liudmyla, psychological violence was the most difficult thing to endure. The pain became duller after the interrogators beat them.

“Beating someone all the time is impossible. But morally, it is feasible.”

There were moments when she no longer feared for her life and just wished for the abuse to end.

Unbearable daily prison life

It was unbearable to endure prison life daily.

“You find yourself in a situation where basic things seem terrible.”

Simple things like having to wash and brush your teeth over a hole in the floor that serves as a toilet and also eating two meters away from that stinking hole that is simply covered with a rag.

“It is unbearable for an ordinary person. It stinks awfully bad there. The substance that is that brought and referred to as food is physically repulsive. When you can’t remember what a haircut is when you look at your body, your hands in horror… I still think that I haven’t removed the prison odor.”

In some places, prisoners were compelled to wash with muddy water from a pond adjacent to the prison.

“You wash in water where dead flies swim, but you’re happy even then.”

The hardest part was the inability to find out what happened to your relatives and friends. Women were constantly told that they were forgotten and that nobody in their homeland needed them. Liudmyla was saved because she eventually stopped being afraid. No matter how difficult the situation was, she refused to show weakness.

Anna recalls being terrified of interrogations. Following them, the women returned bruised and bloodied.

“It makes no sense to lie there because it was terrifying. It’s frightening not because I could die there but because you’re no longer in control of yourself and your destiny. Your fate, your life is in the enemy’s hands.”

According to Anna, she was beaten for a long time during one of the interrogations, then put on a chair, given cigarettes, and asked:

“Why are you roaring? All right. I didn’t touch you; I didn’t kill you. Look into my kind eyes and say: I haven’t done you any harm, have I? And you sit there, simply afraid to look up.”

And we were forbidden to look them in the eyes or their faces. Because they repeatedly said:

“‘Then you will return home and tell your special services everything about us. And I still want to live because I have a child at home.’ And you sit there thinking, I, too, have a child and want to live. What are you doing, man?”

Invictus: “[Russians] feared us …frightened women …they couldn’t break us”

Anna remains terrified. She says she knows in her head that she is already at home, in her native land, but still fears that she will wake up and it will all be a dream.

“For me personally, it was a test of my faith, my fortitude, my thoughts about my entire life,” she says.

The women were completely unaware of their liberation. Liudmyla says that the guards came into her cell one day and told her she had 20 minutes for the meeting. Thoughts raced through her head that it must have been another place of confinement where the guards would take her. And she feared that it would be even worse than before.

“Then one of the women who stayed there told me it was an exchange. She clung to me because she had already spent two years there. And her surname was not on the list. She’s got a small child. The child was four years old when she was captured. Her daughter is now six. This woman has not seen or spoken to her child for two years. And at that moment, I thought it would probably be better to swap this woman because she is younger and has a small child.”

When the women were walking along the road during the prisoner swap and saw a man with a white flag already in Ukraine-controlled territory, Lyudmila said she just wanted to hug him.

“We walked to the buses and gradually began to realize that we were finally free. Many women cried.”

Anna also recalls with exceptional warmth the moment when she saw her family. However, gradual adjustment to freedom was necessary.

“We were still in disbelief when we were brought to the clinic for treatment and rehabilitation for the first time. It’s as if you’re walking around, looking, the women are also looking at you, scared, and it’s not until the end that you realize it’s not a dream. Because we frequently saw the moment when we would return in our dreams.”

Anna admits that she often dreams about the factory, the living, those still in captivity, and even the people who died or were killed. She says that the Russian authorities are reluctant to exchange prisoners as if to protect themselves. The same Russians she encountered during her captivity fear Ukrainians.

Ukrainian women playing expanded role as soldiers fighting Russian aggression

Anna plans to return to the army following her rehabilitation. She wants to return to the forefront. Anna says she is needed there now. After the war, she might leave the military.

Liudmyla does not wish to discuss specific plans.

“I definitely became tougher. And I also realized that I would not waste any more time. I want to take a focused approach to my life because I am an adult and don’t have much time left. I want to do what I definitely must do.”

Several thousand Ukrainians, both military and civilian, remain in Russian captivity.

Olga Golovina is a contributing author at Euromaidan Press. Since the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, she has worked as a freelancer for Geneva Solutions and a fixer for DW. She has almost 20 years of experience working at Ukrainian TV Channels and participating in educational projects. Olga can be contacted at [email protected]

Read more:

- Zelenskyy rebukes ICRC for insufficient efforts to get access to Ukrainian prisoners

- Stories too horrifying to disclose. Over 80 Ukrainian medics tortured in Russian captivity

- Ukrainians in Kyiv commemorate prisoners of war who were killed in Russian-occupied Olenivka 40 days ago

- Ukrainian women POWs stand proud with shaven heads after prisoner swap with Russia

- Amnesty International used FSB-overseen testimonies of Russia’s filtration camp prisoners for their 4 August report – StratCom