Vitaliy Ushakov was a sports manager in Mariupol. He only got to live one month in the apartment bought with his life's savings: Russians bombed it off the face of the earth. He survived bombings in basements, narrowly escaped death, and miraculously drove his family out of the city despite a falling-off wheel. With only a backpack left from his former life, he dreams of getting his mom out of the occupied city and has already gathered a team to help IDPs in Odesa, where he starts his life over from scratch.

It all started on February 24, early in the morning at 5 am, when the first rockets hit Mariupol. We woke up, and it was scary. Walls, windows, and the whole house were shaking. My wife panicked — we didn’t know what to do. My son is seven. He was terrified.

Then, it got worse. Planes started to drop bombs. They wiped houses and whole streets off the face of the earth. This huge, destructive force fell upon us — aircraft bombs, artillery, tanks firing all around. And it all started at once, and every day the circle narrowed and narrowed. Through the windows, we could see the buildings and city blocks burning.

We lived next to the Mariupol Drama theater, in the city center, on vul. Artema. We spent two days in the apartment, sleeping in the hallway, between two walls, with no glass or mirrors. After the heavy bombing started, it got too dangerous to stay inside. Our windows overlooked Azovstal.

We went down to the basement but that wasn’t safe either. We moved to our friends’ big private house with a parking garage. Two days after we left, four aircraft bombs got dropped on our building. Not one window survived then.

By now, our home burned out completely. We only got to live there for one month: we just bought a brand new apartment, and installed all the new equipment, with all our savings — $20,000. I grew up in a poor neighborhood, and my mom and I always lived in a small apartment. I knew about bad life so my wife and I wanted to build a good life. Everything is now gone — my business, cars, motorcycles.

Zabrisky: What did you do for work before the war?

I worked in the sports city administration and was in charge of the presidential program Zelensky’s Active Parks. I managed sports activities for children with disabilities, for the military, and social programs. Mariupol residents are good, hardworking, common people. We had so many factories and plants: out of 450,000 people, the majority were factory workers.

I am also an athlete, the captain of the Donbas basketball team, and a member of the professional rugby team. In one day, it all turned to nothing. And we first thought our street was scary but downtown was hell on earth. Russians razed it to the ground.

Zabrisky: When exactly?

After the 24th of February, we lost track of time.

To this day, time has no meaning. You live one day at a time. Surviving every day.

It started to get harder. Everything just exploded, burned down. You could not hide anywhere. Have you heard of the Mariupol maternity hospital, hospital number 3?

Zabrisky: Of course.

That day, I was right next to it. I drove around trying to find pills for my son. His life depends on the hormonal pills for his adrenal glands' condition. Medicines disappeared from Mariupol at this point, like most things. In three days, the whole city got emptied inside out, to bare shelves in stores and kiosks. You can’t call it looting or stealing — it is just everyone tried to survive the best they could. I simply had to find these pills: my son would die if I didn’t.

I pleaded for help with a high-ranking policeman, at this point a military man, who once trained with me. He sent a car, a driver, and a military officer to help me and we started off to find the pills, amidst the fire.

Russians shelled the central and the wholesale markets, and people trying to find food there were killed by dozens. We heard that over the radio and took a detour, driving along the main street, passing the mobile provider headquarters, Kyivstar. You could still get the connection there so lots of people stood outside, making phone calls. We stopped the car, too: the officer wanted to call his daughter. He started to dial her from the back seat when Russians began shelling the hell out of the place.

Everyone who came to call their loved ones remained there forever, most got torn apart. The officer shouted, “Out of the car! On the ground! Stay low!” I spread out on the ground and covered my head with my arms. The rockets exploded right next to me. At some point, the officer ordered us back into the car and off we drove along the main avenue.

The worst started then. Russians dropped air bombs on the Kyivstar building and at the maternity hospital. As we turned the corner next to the hospital, the aerial bombs and Grads were falling right in front of us. The officer kept shouting, “Left! Right!” like in an action movie, only it wasn’t a movie. I didn’t think we could survive. A piece of shrapnel got our driver.

I realized that my son was in the building that got hit by the air bomb. Just before it all started, friends took him and some other kids there, to visit family. My sisters and my godmother were there, too. I jumped out of the car and started running like mad.

As I ran, they were firing all around, at other buildings, but I just kept going. I saw every window being shattered. I was out of my mind when I got there and ran upstairs, completely out of breath. My family was there, standing around. My heart stopped. Someone said, “The children are okay. They went back about half an hour ago, back to our place.” “Did they make it back?” I thought. It was only a ten-minute walk but every inch of the way was exploding.

Out I ran, and back to our building. My son was there, in the basement. I sat down. I couldn’t breathe or think. It took me about fifteen minutes to come to my senses. Then, I realized that my sisters, their husbands, and my godmother were back there, in the destroyed building. Back I went, running under fire again. My sisters with their cats and dogs sat in the dark bomb shelter, in the Kyivstar building, alive.

My godmother got killed there, buried underneath the rubble. My cousin’s mother-in-law lost her legs — they were torn off — but she survived. She just doesn’t have legs. All people who stepped outside to call got killed. It was impossible to survive. A giant shock wave cut tall trees in halves. I took my sisters and their families back to our basement. This is how we survived.

Zabrisky: How did you live after that?

We cooked at the fire in the yard. A lot of people died there, cooking by the fire. You needed food and water, and you just couldn’t always stay in a basement. You stepped out — and then a bomb fell nearby. Heaps of corpses were everywhere. People were buried in the yards. The rocket “arrived,” killed, and the grave was made right away, just a pit in the ground. If they happened to have an ID on them, their names were inscribed on a manmade sign.

Zabrisky: Did you bury people?

No, I didn’t — thank God, but I drove by the heaps of corpses on the street, with arms, legs, and heads torn off every day. During the day, we had to get water at a working water pump nearby, at vul. Torhova. We found plastic barrels and delivered water to people under fire by car.

After we got more barrels, we found a minibus and, delivered 3 tons of water or more daily — that is, if we could. The shelling, aircraft bombs, and endless mortars wiped the streets and houses off the face of the earth. Every day now, I wake up and see all this in my every dream. I see planes flying, bombs dropping, rockets flying. I suffer from panic attacks and have to take prescription medication.

We also had to get food. When it all started, my friends and I went to the restaurant Uncle Givi. The owner was a great person and he allowed us to cook from the products left in this restaurant for the military and civilians. My friends and I cooked for 800 people a day first, then for 1200 people. Then, the Internet connection was lost. No one could contact anyone. We still prepared 3,000 portions and brought meals for the military to the front line.

We helped others for as long as we could. A lot of acquaintances and friends of mine came from Volnovakha and small urban-type places near Mariupol. Russians destroyed these villages and killed a lot of people. Many escaped to Mariupol. We placed them in hostels and brought things that we collected: food, hygiene products, and such.

I stayed in the basement only after curfew. The parking lot became our home. Elderly, women, and children slept in the cars. Men slept outside, on the spare tires. It was cold. Every morning, around 4 or 5 am, if I was lucky enough to fall asleep, to doze away, I would wake up as the planes were flying by. My friend would hug me and we would close our eyes, waiting to see if a bomb would fall, if we would die then or not. Many people got buried alive. I helped get people from underneath the rubble — women, children.

Zabrisky: How did you escape Mariupol?

The area where we stayed got shelled non-stop. Our car got hit and looked like a sieve from the shrapnel, with no windshield and one wheel was falling off. We had no choice so I drove it to the Primorsky district by the seaport, to a friend’s private house. This area was still okay. My friend’s mom started the fire in a stove. For the first time in several weeks, we took our shoes off. In the basement, the temperature was -7°C. I couldn’t feel my toes. My friend’s mom made borscht, it was hot and good. She baked fresh bread, and cut slices for us, with lard.

We sat there, smelling the bread, and we couldn’t believe it was real. We cried in silence. No one could talk.

In the morning, we got into the car. We have heard a rumor that Russians removed a checkpoint by the city border. Before that, people were not allowed out of the city. Many families with children tried to escape at night but couldn’t see the checkpoint in the dark. When they failed to stop, they got killed. We managed to make it and drove to the village of Melekino, 10 km from Mariupol, along with a lot of other people.

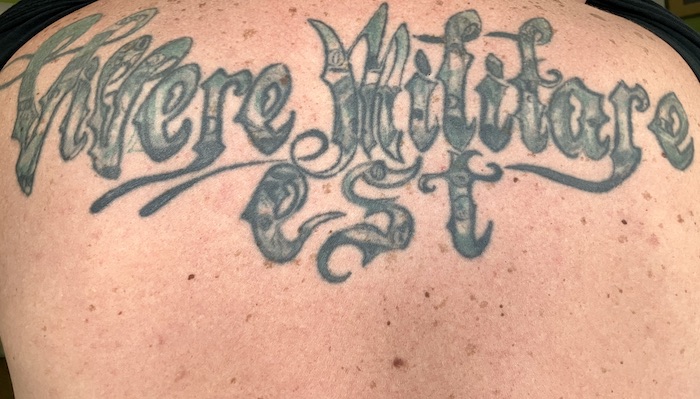

The next morning, we left at 6 am. At 6:15, the Russian tanks entered Melekino. We reached Zaporizhzhia in seventeen hours. Every 500 meters, we had to stop at the Russian checkpoints. Russians ordered men to undress to their underwear, examined tattoos, and interrogated everyone. They searched phones for any connection with the military.

From Zaporizhzhia, we drove at 10 km per hour: our wheel was falling off. We prayed and prayed--until we made it to Dnipro. We had nowhere to go. I had a backpack with documents and thermal underwear, wore my unwashed winter clothes, and had 500 hryvnias in my pocket. That was all I had left in the world.

Then, my friend Denys called me and said, “Come to Odesa.” He gave us shelter, food, and everything to get settled. I am eternally grateful to him.

Zabrisky: And this is how your family stayed in Odesa?

Sort of. After we arrived, we took our son to the beach to see the dolphins in the Dolphinarium. As we looked at the sea, three missiles flew over our heads. In Mariupol, I saw everything but the missiles. My son got so scared. We made a decision then: my wife and kid went to Bulgaria. First, they had some financial assistance but not anymore and it is expensive. I work very hard but that’s all right. I got my first job at fourteen and worked all my life, so it’s not a problem for me. I run an online computer store. I also have to send money to my mom in Mariupol.

Zabrisky: Is your mom still in Mariupol?

Yes. My parents lived in a different district. The last time I saw her was on March 5 when I drove there under shelling to bring her food. After that I couldn’t make it there: I couldn’t even run across the street. Everything was exploding, burning, boiling. And so, my mother stayed.

Zabrisky: Can she get out?

I tried to get her out. I went back to Mariupol from Odesa, took a train back to Dnipro, and drove to Zaporizhzhia. Some people from a local church loaded a bus with humanitarian aid, and a friend and I drove it back to Mariupol through the mined roads and mined bridges, all the way to the Russian and Chechen checkpoints. At a Russian checkpoint right next to the city they told us that a battle was going on and didn’t let us in. We had to leave the humanitarian aid at a village nearby and return to Zaporizhzhia. We tried a few more times but never made it into the city.

On the way back from my last trip, the Russians undressed me, as usual. This time, one Russian officer decided that the tattoo on my back was the national coat of arms of Ukraine. They took me to the commandant’s office and put me in a room next to a young Ukrainian bleeding on the floor. He was shot in the leg and the walls and the chairs were covered in blood.

Zabrisky: How did you get out?

I kept explaining that I wasn’t a military person and was there to save my mother. They let me go but I can’t go back to Mariupol. They now run filtration camps. I returned back to Odesa.

Zabrisky: How is your mom? Can you talk to her?

Life is really hard in Mariupol now. Only basic food. The Russians give out some humanitarian aid: flour and pasta. The price of food is too high to buy anything. No running water. Her building is half-destroyed, and all windows are broken. It’s okay for now while it is warm but I can’t imagine what will happen when winter comes. My mom has to go around to catch wi-fi. Every day, at a certain time, she calls me. I still dream of getting her out of there.

There are no jobs in Mariupol. My friend works for 170 hryvnias a day, hauling corpses. He’s a young man, my age, actually, thirty years old.

Zabrisky: How do Russians treat Mariupol residents?

For the most part, common people don’t have any direct contact with the Russian military. It’s safer to keep your mouth shut, though. A friend wrote to me that one man was imprisoned for selling Ukrainian beer.

Zabrisky: When Ukraine wins, will you return?

For now, I can’t read or watch any news or anything at all about Mariupol. Even one thought, one memory tear me apart from within. I want to live in Ukraine, of course, but I don’t want to go back to Mariupol. It will never be my own hometown the way it was before — never.

I remember everything. Each time a rocket fell next to me, I remember. Every moment is horrifying in its own way. And every day, when things are exploding right next to you, burning, and it feels like you are going to die one hundred times a day. This feeling doesn’t leave you. I am talking to you now but I feel it, it is always with me. I am trying to sort it out now and take care of my mental health.

You know, I was close to the Mariupol Drama theater when the bombing happened. We didn’t know about it because we had no Internet. Just a few hours before that, my friend Serhiy called me. His family was hiding in the theater and he asked me to go find them. I used to go to the theater every day around 11 am or midday, to check about the green corridor, to see if we could leave.

That day, I was busy cooking on the fire outside and I didn’t go. A few hours later, a man came and said that the drama theater was bombed. I felt tears coming because I realized that Serhiy’s wife and kid were there. They were lucky, though, and survived. He managed to come back and get them out of Mariupol — but so many stayed there forever. So many close to me died.

I knew some Azovstal defenders. They are now prisoners of war in Russia. I also knew a lot of regular civilians who also died or were wounded. When someone calls from Mariupol, I am happy but there is always a horrid story. Each person has a horrible story.

I don’t have any videos or photos left — I wanted to make a movie — but we had to delete everything because the Russians were checking our phones at the checkpoints.

Zabrisky: How do you feel about speaking Russian?

I speak both Russian and Ukrainian. We are used to speaking Russian at home, we go back and forth, fluent in both. At work, I write documentation in Ukrainian. It doesn’t matter to me.

We could never think that it is possible, that our “neighbors” as we used to call them, would attack us. We all have relatives in Russia. My father and both my grandfathers were in the Soviet Navy. And now I come to Odesa and the rockets are being launched at Odesa from the ship — it is inexplicable for me. My relatives live in Krasnoyarsk and Murmansk. They used to come to Mariupol in summer for vacation, every year. In 2014, it abruptly stopped. These days, we are not in touch. I don’t feel like reaching out. I don’t know if they know anything about us.

I have been to Russia so many times, to Moscow, and St. Petersburg. I had so many friends, my groupmates from Mariupol industrial college.

Zabrisky: Are you in touch with them?

My groupmates from St.Petersburg were reaching out, trying to find me to see if I have survived. They do not support the war. I don’t hate them, my attitude to them didn’t change. They are just common people. I don’t think they can do anything. Just think about it: what can a regular young man with two little kids and a wife from Mariupol do? He had never served in the Russian army. He just happens to live there. How can I hate him? It is stupid to hate all people.

Yes, I am angry but I am trying to not let this feeling take over me because it is destructive. I am a man of faith. It helps me a lot. I go to church and speak to priests and fathers.

Zabrisky: Is it Christian forgiveness?

Who am I to forgive or punish? I am just an ordinary person who happened to be caught in this war. I can’t either forgive them nor —Yes, I am angry, and I am very sad about it, but forgive or punish? Unfortunately, it is not up to me.

Zabrisky: Who do you think should punish the ones who commit these crimes?

I would very much love to believe that the high providence would punish them. You know, how they say there is a power that punishes people for their wrongdoings with troubles or diseases. Of course, I do not wish it on anyone. Not to one person in this world.

Zabrisky: Even Putin?

Well, even Putin. With Putin, I’d commit the sin, though. For sure. And those, who are supporting him. They are not worthy of being on this planet. They are monsters from hell. The others are the slaves of this regime.

You know, I wasn’t surprised by this war. I just knew that I needed to survive. I was praying for days on end. I think it’s working. A lot of people are saying that they got out with God’s help. So many people told me that their cars were running out of gas but kept driving, miraculously. Just take our car. If the wheel did fall off, that would be the end of us. One needs to believe. If someone is telling me that they are an atheist, I tell them that they would turn to faith in Mariupol.

Zabrisky: I am an atheist and I respect your feelings and your faith. I also hope that people’s justice will find those guilty of these crimes. And I hope that your life gets back on track.

Life goes on. I realized that I need to go on and be useful to people. I gathered a volunteer team and started to fundraise and collect donations. My friends, athletes from the different parts of Ukraine, collect what they can, send it over and I distribute the funds, helping internally displaced persons.

Every day, people from Mariupol come to me for help. I also got involved in the international anti-drug association. My team holds many events. On Children’s Day, in the Odesa Zoo, we organized an event: local restaurants provided meals — sandwiches, ice cream, juice and sweets, lunches, and fed more than 2,000 people. We are planning to do much more and are looking for funds and organizations to support us.

My future is in Ukraine. I don’t want to go anywhere else. There is no place for me outside of Ukraine. I am here; I am surrounded by amazing people. The war reveals true friends and I am so grateful for them. I also know that you have to rely on yourself.

Related:

- War diary: “Terrified of what He saw, God has left Mariupol, my neighbor said”

- Martyred city of Mariupol wiped out of existence by Russia’s incessant shelling

- “At first, I did not want to live.” Ukrainian nurse got married after Russian mine took her legs

- “Dearest daughter, it’s total Hell. Death is everywhere” – Ukrainian father on the frontline

- Escape from Mariupol. “I begged God to let me die quickly!”