Popular American writer Jonathan Franzen recently gave an interview to Russia's Meduza where he expressed regret that "unfortunate Ukraine" became a "pawn" in a "geopolitical battle." His now-former fan, who since February 2022 defends Ukraine from the Russian invasion, sets him straight, from the trenches, where he dreams of an M777.

In his first hit novel The Corrections, Jonathan Franzen refers to Ukraine as "the Ukraine," it's Ukraine's colonial name used by Russia internationally until the late 1990s and, occasionally, even now. In his recent interview with the Russian news site Meduza, Mr. Franzen stated (translated from the Russian original):

"I was shocked by what President Biden and Congress are doing, and especially what they are saying. They actually went to escalate the conflict [it's regarding the US military aid to Ukraine, - Ed.]. Unfortunate Ukraine has become an unwitting participant in the proxy war. [...] Ukraine becomes a pawn in a geopolitical battle between two great powers - and this, of course, really resembles Vietnam."

A Correction (For Jonathan Franzen)

As I stand in the sand, staring, enhanced, far into a field in front of me through the lens of a high-end rangefinder, measuring distances and angles to upcoming aims, and the smoke where our last shell hit is clearing, the colonel is repeating the word corrections behind me.

I’d just relayed to him the distance and angle of our last hit, and he and the lieutenant are calculating new firing data taking into account wind speed, temperature, and our previous hit: the corrections. I cannot overstate the importance of the corrections, says the colonel.

A lieutenant colonel comes by, takes out of a pocket of his uniform what looks to be a page from a book, tears it up into neat rectangles, and throws it down on the sand: there’s your wind speed, boys, he says.

Bits of the page fall in a rough ellipse, like a soft vase broken upon soft sand. He takes two big, meter-long steps to the middle of the ellipse: that’s four meters a second. Tear the page, throw it to the ground: there’s your corrections.

It was as if he was addressing me – I’d just finished re-reading The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen yesterday in bed (a yoga mat on a wooden floorboard). I look around: is there anyone I could tell the story I see here?

Dear Jonathan Franzen, I’m sure you’re so, so tired of this shit, but I have a correction. The gist of it is so simple and poignant that even you couldn’t make that shit up. It’s “Ukraine,” not “the Ukraine.” No definite article, as with other countries – we’re just like them.

The Corrections refers to my country, in passing, as some kind of enclave or region, while Belarus, which gave free rein to Russia to launch their missiles at us from their territory, is treated with greater respect in the same sentence.

I’d always suspended my disbelief there, choosing to refuse the notion that this book that made me wipe away tears on the subway, that I forced upon my reluctant friends, was written by an American man, who sees Ukraine and me just as one would expect, and the story is a lie, all sound, and fury that adds up to nothing at all.

Twenty years later, the, the echoes: a Z on a tank crushing charred civilian bodies, and a guiding light, Zelenskyy, the president.

I’d chosen to believe it was a slip on the part of your editor, they would’ve fixed it if they looked over the text one more time. Hell, I was saying “the Ukraine” occasionally until like the fifth grade.

Now I am standing in the sand in a uniform, in my pocket a phone randomly buzzing with a chat’s Discourse On Franzen. I find a moment to read a screenshot from Meduza, a Russian media interview, and am crestfallen.

How could he speak to Russians, how could he say these things! A friend says, I never managed to get past one-tenth into The Corrections, I hated the guy. I think of responding how, yeah, I know, I hate Chip, what a fucking jackass, he’s just like me, but instead I type “he also calls us ‘the Ukraine’ in the book.” The message won’t go through.

Now, late at night, again where I finished The Corrections yesterday, I’m imagining you tell your editor, a shadowy figure over a desk in a dark room, the light from a desk lamp turning your glasses all walleye, ‘The 'the' stays. I know what I’m talking about." You may or may not be smoking a European cigarette. Didn’t happen, who cares.

Have you ever considered laser eye surgery, Jonathan? I’m clutching a $10,000 rangefinder, the smallest in its class, in the middle of a sand storm. The wind has picked up. The rangefinder’s laser stumbles over the sand in the air, returning a distance value of D = 8.3M. "Not good," I yell to the colonel.

Man Interviewed Says He Doubts His Abilities To Judge Good and Bad, Proceeds To Judge.

Man says, how can you write off an entire country just because it’s got an evil tyrant at the helm.

I tell the man: my American, no-one’s writing anyone off; in fact, we’re writing it all down. I tell him: my dude, Russia is a country all right, with a history, and its days are numbered, and it’s about fucking time we took a long hard look at what the history of that country actually was.

And I tell him that I was born in a country that saw that history unfold at its front door and had been a long-suffering neighbor in a house that had been robbed many a time. Even in my 27 years, I’ve had a front-row seat, and I hated the view.

Who wrote who off? I hold the people accountable. What happened to all the "would you kill Hitler?" party talk, I remember that was a thing at parties. Or do Russians usually say "I’d probably sit it out and try not to think about it"? Can that be cured? These people have a Hitler, and it’s been twenty years, and nothing’s happened!

Man says, now’s the time to come to Russia and support those opposed to the government. Now’s the time to spend your time, money, and mind there, pay taxes, now is the time to pay for Russian oil to make sure the inflation does not hit too hard those poor Russians that are opposed to the regime, even if you end up mostly sponsoring a genocide. Can’t forget about those good Russians, they’re good folks, they didn’t vote for him, never hurt a fly, they’ve sat at home and been real quiet for twenty years, cause Russia is scary stuff.

Man says, did someone expect literature to prevent this? Aren’t books a bit like apples, and would you blame yourself if you ate apples from a Russian garden and the apple trees could not stop the war? Oh, man. Did you buy the apples? Aren’t apples a bit like gas and coal, and would you blame the EU if it paid 35 billion euros (this happened) to Russia and it didn’t stop the war? No, dude. Both with the apples and the gas, I’d feel pretty fucking shitty and complicit.

Here’s the thing, man. Ukraine is a country. Always has been. Our history has not differed much from many countries of the world you would not deny an agency like that in an interview with the Russian media.

An American seems to believe this is, again, about America, and boy does that help Russia – let’s doubt Ukraine exists, make it about the superpower beef thing, and if the battlefield (that I just happened to have been born on) gets genocided a little, well, tough. Russia is killing Ukrainians, but yeah, they meant the USA, who cares, starts with U, a dictator gets confused.

No.

Russia and us, we had a history for centuries, from way before the Native Americans were first told to beat it. We sat next to a bully all school year and he beat us up and took our lunch every day.

This is not a war between Russia and the USA. We did not "become involved in a proxy war" – I can’t believe I have to say this – the Russian Army entered Ukraine and Russian soldiers began a genocide, murdering, raping, torturing and putting into camps people of all ages, starving us to death in besieged cities, capturing and stealing our grain supplies, burning our literature in schools and libraries.

Their methodic perverted cruelty, their giddy slaughter, is aimed at Ukrainians specifically, it is the culmination of centuries of shit they put us through, hating us, envying us – this is not new. This is just the end of the school year, when the quiet kid calmly takes off his glasses and socks the bully in the jaw, hard.

Every day since February 24th ranks somewhere among top 100 worst days of my life. And you speak as if I am an idiot, fooled into obeying something I don’t understand, while I just want the murder to end and I ask the USA for ammo.

This laser I am holding is so powerful, I could probably pop people’s eyes like popcorn.

As an artilleryman, let me make this plain: I WANT THE M777. I THINK IT IS GOOD, AND I LIKE IT.

I want one so bad. I have been training on weapons using 6000 mils but this rangefinder switches to 6400 NATO mils with a couple of clicks, and I am adaptable too.

I’ll type up a neat manual for my fellow artillerymen if there’s no Ukrainian one, and I want to fire the M777 at Russian soldiers who are trying to kill me, who are killing as I type this. I have a mind of my own and there is no moral wrong in me wanting this.

I, newly a Ukrainian soldier (because I did not want to die), am asking for weapons (because I do not want to die); it just so happens that the Ukrainian president does, for the first time in my life, speak for me, and is relaying my message to the world.

It is a feeling I have never known before, and it brings me to tears if I think about it too much, a sun of righteous anger so bright it makes my eyes burn.

If I could hit a sniper in the scope with this laser, it would probably hella completely fry up a brain. Man, it’s like that bit in Infinite Jest.

On The Simpsons, I hit Jasper in the eye with my laser: "My cataracts are gone. I can see again"; then he is gruesomely obliterated by a 120 mm shell.

The counterfeit Monopoly

My twelfth New Year’s was marked by my first attempt at willful abandon of consumerism. Year after year I’d seen, with increasing clarity, various hints my parents would drop regarding how unaffordable for us the presents I wanted were: a German H0 gauge train set, a camera; but I chose to not understand, and my parents would somehow deliver.

Perhaps, my train set was one of the simpler, passenger variety ones (an engine, three identical cars), but it was of the very same brand I’d carried around catalogs of, with my set present in the back pages. It became a permanent fixture on the carpet in my room for years, even though the motor of the train quickly took in hairs and dust from the carpet, and it wouldn’t depart unless I gave it a push or dragged it along.

Seeing an object from a catalog of a German toy company materialize in my bedroom was my first taste of the realness of an unfathomable world beyond Ukraine. Idly sitting in school and considering that colorful pictures of train models in catalogs reflected reality, that these trains existed somewhere in the world, and were played with by kids like me, made my head spin, like trying to imagine how much a million of something is.

Next year, at twelve, I thought, it’s time to be an adult and help my parents out a bit. I asked them for a Monopoly, equating my willingness to embrace a less identity-shaping present with maturity (unlike the train, I knew I had no way to play it daily), and thinking a board game had to be cheap enough to save the sides of the transaction the awkwardness. I’d played Monopoly before, with my cousin and her beautiful friends (and occasionally in the less terrifying company) a few times. It is all an anxious blur, but the first time we played it I was probably somewhere between the age of admiring the craftsmanship on the car figurine and wanting to put it in my mouth.

On the evening of New Year’s Eve, my father came home at the usual lateness, with a shopping bag in his hand that seemed to carry a flat box – which had to be my Monopoly, had to be. He did come into my room and put the bag on my bed, standing by it with a stilted smile. He wished me a happy new year in his ironically formal, uncool way; the bag contained a local generic version of Monopoly, called Monopolist.

I wasn’t then privy to the pitfalls and virtues of generic products; the thrift of a plain cereal or apple juice; the box seemed identical to my best recollection of real Monopoly, and yet, in the substitution of one sans serif font for another and dethroning of monocled Mr. Moneybags, the magic had somehow been drained from the box.

I knew my father couldn’t have possibly bought the wrong game by accident: some of his most prized possessions were a Parker pen, a vintage Levi’s belt with a beautiful relief buckle, and a Hohner harmonica. His stoic insistence on only buying licensed CDs in a country that record labels barely knew existed meant that his Bowie catalog was sadly lacking, limited to 1995-2003 and a hits compilation.

He prided himself on having never been a smoker; his possessions over many years amassed light signs of wear, but were, otherwise, anonymous, as if out of respect for the things, or in preparation for having to sell them. He seemed intent on living by the slogan "the best or nothing," and life had taught him a hard lesson on how often he’d have to choose the latter.

"That Monopoly is SO expensive!" my father finally said, wrinkling his nose in mock disbelief, his smile now seeming apologetic, and I smiled too. We sat on my bed quietly, both feeling guilty despite having done nothing wrong, both smiling to make each other think we were happy. Somehow, for no reason at all, this evening had become one of the saddest of my life. I loved my father and pitied both of us so, and there was nothing I could do.

The properties on the board, when they came to me, instead of the sophisticated Park Lane and Pall Mall were all Kyiv streets: the stuffy, hot Khreschatyk, that as a kid I couldn’t see for all the tourists, Lesi Ukrainky Boulevard, which I only knew as a drudgery of smog and traffic on the way to my father’s office where I pirated Bowie mp3s.

The dream of worldliness had been evicted by the smell of printer ink. Instead of weighty and peculiar metal player tokens of Monopoly, there were plastic cones, instead of festive red and green figurines of houses and hotels - cardboard disks with house and hotel icons. Their cardboard was thick, layered like a cheap cake, with a little sharp bump on one side of the circle where it had been machined out of a larger cardboard piece.

I took a few out of a ziplock bag they came in, made sure they held nothing of interest on the reverse, and limply put them down. I surveyed this newly conquered domain, disheartened by how barren it was, my face flushed with sudden hot disappointment.

Who could stay in a hotel like this, who could flatten themselves to the two-dimensionality of this cardboard disk? Could I ever ask that of any of my few and precious three-dimensional friends?

And as my room over the years had become shameful to me, embarrassing to show to school buddies, so had this box, in a matter of minutes, because it too contained evidence, fresher and more incriminating, of how poor and dull our family surely was. I saw a fundamental truth so clear it was like steam had been wiped off a mirror in my mind.

I never dared to inflict upon my father the shame of playing that game; the next morning, I quickly stowed the box away on a low shelf under old coats in the wardrobe, and never once took it out after. Years later, whenever it caught my eye as I took my father’s old coat, the word MONOPOLIST in generic font, an unplayed game’s silent reproach, was a punch in the heart, a rush of guilt to the head.

An ex-colony does not get to hang out with empires

What has private Ukraine in my head known but this? Very little. A much-corrected history of taught inferiority, the state of being lesser, existing as a Russia with a twist. Our history books that I was taught on looked lame, seemed fanatical, and were subjective: and our history seemed impossibly unfair. I couldn’t internalize the terrors we’d been through as a kid. How easier it was then to almost anticipate the Western leftist discourse: we must’ve been stupid to let ourselves get genocided so often, #peace.

Actually! In the 12th century Moscow pops up on the map (Kyiv has been around for over six centuries, and a capital of proto-Ukraine, Kyivan Rus, for three).

The Mongols siege Kyiv and occupy, eventually ceding control to Poland and Lithuania. By the 15th-century things get so dire under Poland that a due rebellion is carried out. Meanwhile, the Golden Horde export us as slaves to the Ottoman Empire, totaling about 2 million people over the next two centuries. Then, in the 17th century, a Cossack Hetmanate, the direct ancestor to Ukraine, is established through another rebellion and finds itself surrounded by the same tedious enemies: Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania to the West, Tsardom of Muscovy to the East, and Ottoman Turks to the South.

The Cossacks, an anarchic, cosmopolitan, and intelligent bunch, had little respect for the antiquated imperial wretchedness surrounding them, and had no rulers but instead a Hetman – military leader that was elected democratically. Unable to watch their way of life fall by the wayside, Russia struck deals with Cossacks, until in 1775 Russian Tsar gave an order to her general to occupy the Cossack Sich, as a state that had no right to exist.

Enter the night of Ukraine: we are nowhere, split between Austrian and Russian empires for the next 150 years. The Ukrainian language is banned from study and use. Ukrainians are serfs – peasant slaves for sale, including our most beloved poet and painter, Shevchenko, his self-portrait now on the 100 hryvnia bill.

WWI reaches us a colony in the process of self-determination, again, fighting for our right to exist, but the world turns inside out, and Ukrainians from fighting outward must switch to fighting inward, on different sides of the front. Now it is so dark blinking makes no difference. The USSR comes, and in modernized misery, starves millions to death by exporting all our grain in 1930s Holodomor. Millions die in WWII and millions in Soviet repressions.

The light comes moments before I open my eyes: a chance to catch our breath, 30 years of freedom, 27 of which I have lived. There’s no way it really was as bad as the history books say, right? Watch this, Russia says.

I’ve lived my adolescence in books and Bowie mp3s, my adulthood in screens and on keyboards of word and melody. I’ve been inside yet looking in, I let the world tell me about the country outside my door, and they had little good to say.

Fundamentally, I think, it just wasn’t obvious, growing up, that one couldn’t blame the newly free Ukraine for the dowdiness and boredom of my childhood. When I was born, it had only existed for three years.

But unlike Russian propaganda, the authority of a foreign people that have never tried to genocide you, but still saw you as lesser, we were not immune to.

This ends now, though. The scales fall off eyes country-wide and now we know everything Ukraine has been told about Ukraine was either wrong or a lie.

When I was a musician, I would occasionally venture into Europe, whose point of view on us I had internalized, to play a show, and I would feel a refugee for the time spent, always conscious of my behavior and clothing, always worried about breaking some unspoken rules in this high society, always wanting to fit in.

I’d agree with most of what Europeans had to say about Ukraine, complicit, I’d even pile on about how terrible Ukrainian music is, how bad the architecture, and how insufferable the arts community is. I had something to prove, speaking my acceptable English, wearing my one good coat (my father’s), playing the best music I could make – all to back up a claim that I am, while second-rate by origin, the same; yet I felt like an exotic animal all the more I tried.

People seemed intent on sussing out what was different (bad different) about me, what character flaws exactly it entailed that one was a Ukrainian. And familiar blameless guilt would return, be it in a Berlin bar or meeting the eye of an airport official, who lingered on my passport for a bit too long, while I would be repeating a flawlessly pronounced thank you, have a good night in my head, which would come out hoarse, rushed, or mangled.

We were always told we were stupid. An ex-colony does not get to hang out with empires. All the cool bands are playing tonight: NATO, European Union, The Human Rights, but the bouncer says, looking away, sorry, buddy, not tonight. Have a night of your life.

The lies, the lies, why did I ever listen. On day one, German Finance Minister Lindner told Andriy Melnyk, Ukraine’s Ambassador, that Ukraine had mere hours left and there was no use in helping us now – he was wrong, or he lied. He probably had his best apologetic smile on, too. Mere hours ago, then, Putin had refreshed Russians’ memory on the big, strategic, infuriating things they’ve been taught about Ukraine. If his nose grew for every lie told, he would’ve violently destroyed the camera and sniffed the inside of the camera person’s brain.

If I had listened to Minister Lindner and his German authority, I may have never had enlisted, instead cowering in the bathroom, guilty, waiting for the rocket. If I listen to American leftists now, I am told Ukraine either never existed, or is all Nazis, for not wishing to return to Mother Russia’s rotten womb.

Gee, I wonder who told them that. They’re all for peace, naturally; shame peace, in this case, means stop struggling and enjoy your rape. And naturally, our rejection of surrender is seen as fighting in someone else’s interests – because weren’t we Russia just recently?

You call this a proxy war, which echoes the Russian narrative, assuring that rare Russian soldier that didn’t hate us already that by killing a Ukrainian in his home he is somehow fighting the USA. He is freeing a colony from its new empire. It’s a shame that by this logic we are all not only Ukrainians but also American agents.

Everything I’ve been told about us was a lie

I’m done believing we’re the stupid ones. I’m done listening.

Fascist Russia’s Z, a badly-drawn half-swastika, I discovered, has at least one true meaning – Russia had no plan B for this war, and this cowardice and chaos is it, the last, the only plan. What we’ve been through already contains an entire alphabet of erasure, destruction, mass murder, in specific events, and this is its last letter, their last attempt. The fascist of today gets no chance: he is knocked out before he can finish drawing his swastika. Soon, after this, we will finally be free.

I don’t know why the past was what it was, why a litany of our faults to a melody unresolved. Where we are thrust now the only possible music is stripped of harmony and only the rhythm, a fish skeleton of a waveform, remains. To write the first chord, we play on towards a beat of our own: the mortar launch a kick, the crash on Russian metal a cymbal, until nothing is left but the pulses of our wet hearts. We have been fucked with by nerd ass jock empires all our life.

Now at this war, I have proof everything I’ve been told about us was a lie. I discovered that we are wonderful.

I printed your college literary zine, man. Small Craft Warnings, Swarthmore College. I was so fascinated by a possibility of a sudden plunge, out of time or place, into a wealth of young and careless poetry, that it just about made me dizzy.

I wanted to print up and read a whole lot of them, go through them like historical documents, and I dutifully started with the edition where you took over as editor, and your future wife’s ambitious poem about anniversarial dismemberment, was. I read your poem too, and a short story about the church, and it gave me hope that I also didn’t have to always write the way I do now. It made you seem more real.

And that Russian media interview was a correction, Jonathan Franzen, and now you are farther away.

God, what terrible timing, I thought, for about a millionth time in life: I’d just given my girlfriend an ebook of The Corrections I had hastily bought for eight bucks off eBooks.com. It was then only downloadable as some disgusting DRM-infested riddle of a file that neither of us have, and never will, manage to open. I just wished I could somehow put my well-used paperback into her hand from here, to reach her from this war.

I don’t know if she’ll finish the book now, though. Jonathan Franzen, it turned out, to a Ukrainian is an ambassador of the country of This-Shit-Again-Land. You can kind of foresee it in the Lithuania chapter, I guess.

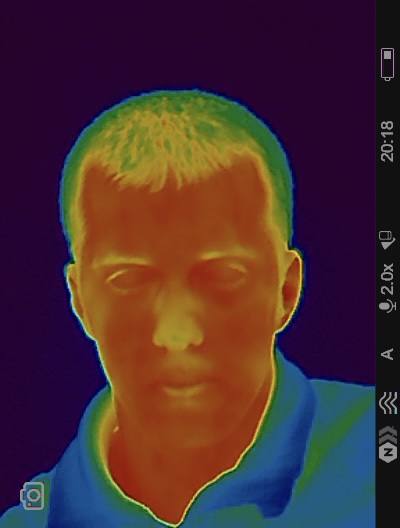

I don’t know if they really were the struggling exporter of sand and gravel pictured in The Corrections then, but they certainly make state-of-the-art thermal scopes now.

Today I called my girlfriend to tell her all this, we exchanged loud, ironic hellos. Then, clipped chunks of her voice telling some story I’ll never hear, then an air raid warning and my phone went dead, and I lost my heart.

Timur Dzhafarov is a Ukrainian electronic musician and visual artist from Kyiv, since February 2022 he serves in the Armed Forces of Ukraine.