The repressions Russia is unleashing against the Crimean Tatars today are an “intentional extermination of his people” that continue Russia’s persecutions of the 18th, 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, he tells Crimean Tatar activist Luftiye Zudiyeva.

Remembering the past

Shukri Seytumerov knows every street, every alley, every building of old Bakhchisaray. He is a historian and ex-head of the Department for Monument Protection of the Bakhchisaray Historical and Cultural Museum. He is familiar with the history of each house and all the local mosques, of which there were more than forty before the Soviet era.

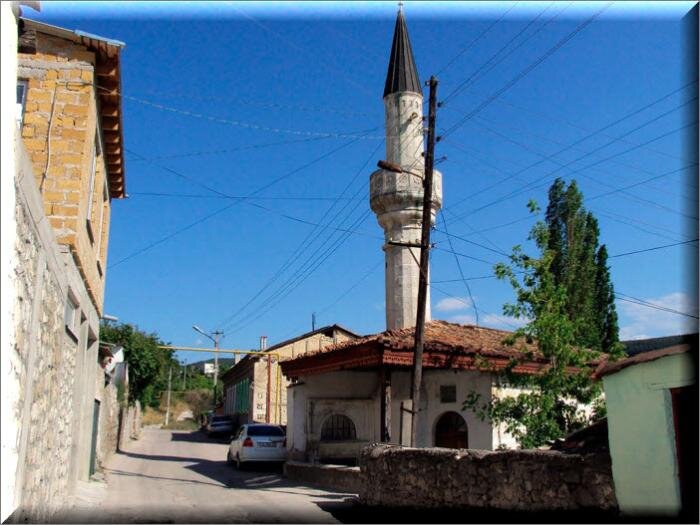

The car stops at the Takhtali-Jami Mosque. It was built by the daughter of Khan Selim Giray – Bekhan Sultankhani in the 17th century and is located just a few minutes’ walk from the Khan’s Palace. It was originally constructed with wooden boards, which is why it is called “Takhtali Jami – Wooden Mosque”. In 1923, the mosque was closed for visits and religious ceremonies, but in 1979 it reopened to visitors.

Shukri Seytumerov stands near the mosque and, with a slight tremor in his voice, recounts the story of his family’s deportation and exile to Siberia.

“We’re standing near the location of my grandfather, Mustafa Murtaza’s old home. He was taken away in 1938. My grandfather and my mother lived in a house that no longer exists, but the territory still belongs to the Takhtali-Jami Mosque.

One evening, two guards came and took my grandfather away. Later, his family learned that he’d been arrested along with several religious persons by the Bakhchisaray regional department of the NKVD. His cousin, a surgeon trained in Istanbul, was also arrested. They’d been denounced by some men who reported that my grandfather had a newspaper with a photograph of Joseph Stalin in the wrong place, and that they’d heard my uncle voicing disparaging remarks about Stalin’s speech. No one ever saw them again. My mother was deported from Crimea in 1944,” says Shukri Seytumerov quietly.

Crimean Tatar Mustafa Murtaza, born in 1882, was a native of the ancient village of Salachyk, located on the outskirts of Bakhchisaray. He received a higher spiritual education in the Zyndzhyrly Madrasah (school) and served as imam (holy man/priest) at the Takhtali-Jami Mosque. The archival certificate that Shukri Seytumerov shows me says that Mustafa Murtaza was sentenced to death at the age of 56 for “participating in a counter-revolutionary nationalist group aimed at liberating Crimea from the Soviet Union and annexing it to Türkiye, and systematically carrying out counter-revolutionary terrorist propaganda”.

Mustafa Murtaza was arrested on 12 February, 1938. He was imprisoned in Ekaterinskiy prison in Simferopol, which is now the only pre-trial detention center in Crimea. An extra-judicial NKVD troika sentenced him to death and confiscated his property. Murtaza was executed on 4 April, 1938.

“Judging by the materials related to my grandfather’s criminal case, there were two witnesses. Their testimonies were found in the state prosecutor’s version. We know the name of one of the witnesses, as it’s been in our family for decades and has been passed by word of mouth,” continues Shukri Seytumerov.

The other name was classified. The interrogation was conducted by junior lieutenant Starodubtsev of the Bakhchisaray district department of the NKVD. The family has also remembered his name.

On 18 May, 1944, Mustafa Murtaza’s family – his wife, 38-year-old Reykhan, and two daughters – were deported with thousands of Crimean Tatars from their homes in Crimea to Central Asia. The family was forced to live in Samarkand Oblast of the Uzbek SSR. According to official data, which differ greatly from that of historians and human rights activists, 183,155 Crimean Tatars were deported from Crimea in 1944. 46% of them died during the first year and a half of exile,.

“On 5 July, 1990, the prosecutor’s office of Krymska Oblast announced that my grandfather’s case fell within the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated 16 January, 1989 – “On additional measures to restore justice in relation to the victims of repression that took place in the 1930s-40s and early 1950s”. Thus, the prosecutor’s office recognized that my grandfather had been illegally persecuted and convicted. But, no one could return him from the dead. Moreover, the men responsible for his arrest and execution were never prosecuted,” says Seytumerov bitterly.

Russian FSB targeting Crimean Tatar activists

But, the Tahtali-Jami Mosque has played yet another tragic role in Shukri Seytumerov’s life story. 82 years later, the past has returned to haunt his family. This time it concerns Shukri Seytumerov’s two sons.

“We were finally able to return home from exile to Crimea. In the early 1990s, Takhtali-Jami was open to anyone who wanted to learn more about their religion. Our religious instructors began conducting classes (sukhbets). We were all eager to learn what we’d forgotten or lost over the years due to deportation and exile. This is a natural desire in all human beings.

In fact, this mosque holds a special place in our hearts. First of all, it was a place where I and later my children received basic knowledge about Islam. Second, it’s a place that’s associated with grief, pain and loss,” says Shukri Seitumerov.

Today, Shukri Seytumerov’s sons – 29-year-old Osman and 33-year-old Seytumer – are in prison. In March 2020, they were arrested by the Federal Security Service of Russia (FSB) in Bakhchisaray on charges of terrorism and anti-constitutional activities.

The Takhtali-Jami Mosque, which their great-grandfather frequented and where Osman and Seytumer gathered with other Crimean Tatars to pray, had been bugged by the Russian FSB. The meetings, conversations and prayers of the Muslim congregation were monitored and recorded daily, eventually leading to several arrests and criminal trials. On 11 March, 2020, the FSB arrested Shukri Seytumerov’s two sons and his wife’s brother, Rustem Seytmemetov.

More than 100 Muslim Crimean Tatars have been arrested in occupied Crimea. Many of them are closely related.

According to the criminal investigators, the Seytumerovs were preparing “a violent seizure of power through total Islamization of the local population”. The accusation is based on two wiretaps in the mosque and the testimony of two secret witnesses known as “Kerimov” and “Osmanov”, which cannot be verified. No evidence of weapons, explosives, ammunition or terrorist plans was produced during the trial.

“It sounds strange, but my sons are accused of visiting the Takhtali-Jami Mosque, praying and discussing spiritual, religious and historical topics with the others. Speaking in court, my youngest son Osman pointed to the fact that mosques were now forbidden to Muslims, and that discussions about the tragic history of their people posed a direct threat to the constitutional order of the Russian Federation. Today, Crimean mosques have become places of suspicion and fear, where the FSB searches for new victims,” says Shukri Seytumerov grimly.

Since the 1990s, the mosque has organized sukhbets, discussions, festive dinners during the Ramadan month, and duas on Fridays (prayers of invocation, supplication or request). In the evening, between prayers, the faithful discuss the history of the Crimean Tatars, politics and daily life. There are no secrets or hidden messages. On the recordings, one can hear people freely entering and leaving the mosque.

“They, the FSB, couldn’t come up with something new. They’re following in the footsteps of their ancestors – the notorious NKVD – but they forget what fate befell their ancestors – Beria and his ilk.

82 years later, the descendants of the same NKVD, now called the FSB, break into our family home, arrest three members of our family, and charge them under exactly the same article as the one that our great-grandfather was charged with. History repeats itself – like our great-grandfather, we are accused of visiting a mosque, and will serve our sentence in the Ekaterinskiy prison in Simferopol,” said Shukri Seytumerov’s son Seytumer during the trial.

Intentional annihilation of the Crimean Tatar people – both then and now

“82 years ago we had the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, also known as the RSFSR. Today we have the Russian Federation, also known as the RF. The same state, only the letters have changed, but what they’ve done to my grandfather and to my sons in the space of almost one century is basically the same. This is the intentional extermination of our people,” concludes Shukri Seytumerov.

We return home. Shukri takes out a thin paper folder with several documents. It contains material that he’s managed to collect about his murdered grandfather – copies of archival certificates, black-and-white photographs, and yellowed copies of protocols from the case file. For the Seytumerov family, this is an important archive, to which new documents have now been added.

Shukri Seytumerov sighs and closes the file. He underlines that there is no normality in Crimea, that Crimean Tatars are being persecuted and arrested every day. He invites skeptics to look at the family documents, and then look him in the eye and tell him that his grandfather and his sons had a “fair trial”.

The history of the Crimean Tatar people shows that these persecutions go back many, many years. They began several centuries ago, and continue today. Seytumerov’s grandfather was executed, his mother was deported, and his sons were imprisoned.

“50 years after my grandfather was executed, the prosecutor’s office ruled that there was no evidence pointing to his involvement in such crimes.

Do we now have to wait another 50 years for someone to come to their senses or for the government to change?”

Shukri Seytumerov is convinced the repressions against the Crimean Tatar people will continue. The criminal case against his sons reflects the tragic reality of the entire Crimean Tatar people today. Since 2014, hundreds of men have been imprisoned or sent to penal colonies for “terrorism and extremism”. More than two hundred children have become orphans. Shukri Seytumerov’s own grandson is growing up without a father. Tens of thousands have been forced to leave their homes and emigrate.

Read more:

- Crimea and the Crimean Tatars: Centuries of competing claims and forgotten history

- Documentary “Crimea. As it Was” shows the very beginning of Russia’s occupation of the peninsula

- Moscow’s claims of ‘historic right’ to Crimea don’t stand up, Popov says

- How Stalin destroyed the Crimean Tatar intellectual elite

- Ukrainian parliament declares 1944 Soviet deportation of Crimean Tatars an act of genocide

- 7 myths driving Russia’s assault against the Crimean Tatars

- Why the Kremlin fears the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatars

- Crimean history. What you always wanted to know, but were afraid to ask

- Portnikov: Crimea’s past and Kremlin’s falsifications

- Sürgünlik: Remembering Stalin’s deportation of the Crimean Tatars in 1944

- Russian occupiers continue to destroy history and culture of Crimean Tatars

- Ukraine’s water blockade of Crimea should stay, because it’s working

- Crimea and the Crimean Tatars: Centuries of competing claims and forgotten history

- Documentary “Crimea. As it Was” shows the very beginning of Russia’s occupation of the peninsula

- Moscow’s claims of ‘historic right’ to Crimea don’t stand up, Popov says

- How Stalin destroyed the Crimean Tatar intellectual elite

- Ukrainian parliament declares 1944 Soviet deportation of Crimean Tatars an act of genocide

- 7 myths driving Russia’s assault against the Crimean Tatars

- Why the Kremlin fears the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatars

- Crimean history. What you always wanted to know, but were afraid to ask

- Portnikov: Crimea’s past and Kremlin’s falsifications

- Sürgünlik: Remembering Stalin’s deportation of the Crimean Tatars in 1944

- Russian occupiers continue to destroy history and culture of Crimean Tatars

- Ukraine’s water blockade of Crimea should stay, because it’s working