The EU has imposed a partial oil embargo as part of its 6th sanctions package. Yet, between 24 February and 31 May, EU countries paid over EUR 55 billion for oil and gas imports from Russia. That’s the equivalent of roughly 15,000 T-14 Armata tanks or 60,000 cruise missiles. The EU may pay Russia an additional EUR 100 billion by year-end. Here is what can realistically be done to exhaust Russia's petroleum-based incomes -- and what stands in the way.

What does the oil embargo mean?

The European Union has introduced an embargo on Russian oil imports. The embargo will cover all Russian imports by ship. In addition, Germany and Poland agreed to stop buying Russian oil imported by pipeline. Together, this may cover less than 90% of Russian oil imports to the EU.

However:

- Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia are allowed to continue importing Russian oil by pipeline (which represents roughly 13% of Russia’s oil exports to the EU). This is the first time since February that the EU allowed exceptions for specific countries in its sanctions against Russia.

- The international oil prices initially climbed on the news of the oil embargo. At least in the short term, Russia’s income from oil sales will remain stable.

- The embargo will only take effect from 1 January 2023. Until then, Russia may possibly earn an additional EUR 100 billion from oil and gas exports to the EU.

Forbes predicted that “when in six months Europe will give up crude oil from Russia, a huge amount of [Russian] energy resources will not find another demand.” In the meantime though, Russia continues to receive tens of billions to continue to fund and re-arm its military. The embargo may come too late to save Ukraine.

Has the EU done enough, having imposed a partial oil embargo?

This is doubtful. By the nature of the industry, oil imports can be re-routed very quickly in many instances.

Crude oil cargoes are available in large quantities – in many cases, an oil cargo changes ownership many times once it leaves its port of departure. Even in the absence of an EU oil embargo, some companies have avoided buying Russian oil – either due to reputational reasons (e.g. Royal Dutch/Shell) or because of commercial risks (e.g. no insurance being available for Russian oil tankers) or because they were directed by the government to do so (for state-owned companies).

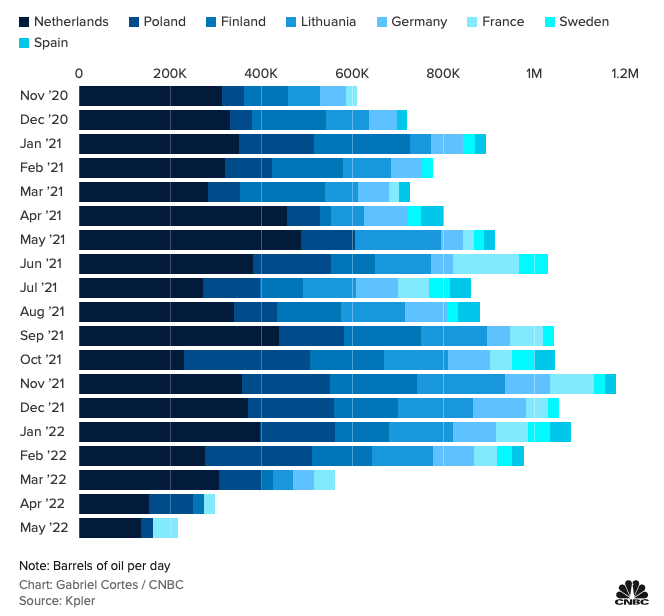

Several EU countries – including Germany, Netherlands, and Finland – have already significantly reduced their Russian oil imports since 24 February (see chart below). But other EU countries such as Italy and Hungary have not tried to reduce Russian oil imports. It should be possible for the whole EU to go the extra mile more quickly.

There are, of course, some difficulties to overcome. Some Soviet-era oil refineries in Eastern Europe have been built to suit Russian crude oil and their equipment must be re-engineered to receive other crude oil types. Crude oil imported by pipeline from Russia to Hungary or Slovakia must be replaced with something else.

However, technical changes to equipment could have already been made since 24 February, while alternative pipelines can bring oil from coastal ports to these countries. A recent Euromaidan Press analysis suggested that even Hungary could replace all Russian oil imports within a year, if there were the political will to do so.

Hungary can switch to non-Russian oil in less than a year, energy expert claims

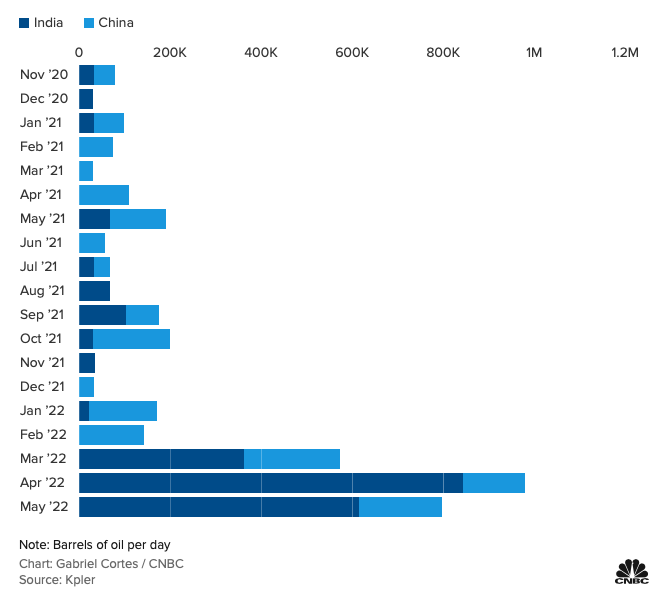

One of the big holes in the EU sanctions is that Russia can find buyers in other parts of the world. Since February, Russia has already been able to divert many tankers to India and China (see chart below). The Russian state budget lost a lot of money, as the Russian oil is now sold at over $30 discount on the normal oil price, but Russia’s oil exports of about 8 million barrels/day are close to pre-war levels.

But again the EU can do more to stop this from happening: by putting pressure on other countries to stop buying Russian oil, by withholding insurance for Russian oil cargoes, and, above all, by banning EU ships from carrying Russian oil. However, a plan to ban the EU shipping industry from carrying Russian crude has already been dropped earlier because of the opposition from some EU countries.

The scope of the EU energy dependence on Moscow and practical ways out

What about a gas embargo?

EU countries paid about EUR 25 billion for Russian gas imports between February and May.

Many EU countries, including Germany and Austria, continue to oppose an embargo on gas imports. An embargo on gas imports is unlikely to be even discussed by EU leaders as part of the 7th round of sanctions against Russia.

Russia has imposed a partial gas embargo on itself by cutting off gas supplies to several countries. In effect, Poland, Bulgaria, Finland, the Netherlands, and Denmark have been cut off from Russian gas.

However, this was a partial victory for Russia, as it helped to blackmail other countries to pay for gas in rubles, which undermines EU sanctions against Russia. Companies from several countries agreed to pay for Russian gas imports into new Russian bank accounts at Gazprombank. They include RWE from Germany, ENI from Italy, Engie from France, and OMV from Austria.

We need to acknowledge that gas imports from Russia cannot be replaced as quickly as oil imports. Gas requires physical infrastructure: you either need pipelines to bring the gas directly from the gas-producing country (e.g. Russia-Europe, North Africa-Europe) or you need Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminals to re-gasify gas that is transported from producing countries by ship in liquid form. It takes years to plan and build LNG terminals. Whilst Poland anticipated Russia’s aggression a long time ago by building an LNG terminal, for example, other countries like Germany have not done so.

But there are solutions too. Lithuania became the first country to stop imports of Russian oil and gas altogether. It is possible to lease LNG terminal ships, which can re-gasify and store the imported gas. Following Russia’s decision to cut off gas supplies, Finland was able to quickly lease an LNG ship that will be in place before the coming winter. The ship will be hooked up to Finland’s national pipeline system and LNG will be imported from third countries. Elsewhere, the existing onshore LNG terminals can expand capacity. Poland has been in talks with the Czech Republic to expand the Polish LNG terminal and then re-export some of the gas to the Czech Republic.

The International Energy Agency says that the EU would be able to replace more than half of its Russian gas by the end of this year. A gas embargo with a final timeline sometime in 2023 would be realistic.

But all of this is expensive. Countries like Germany oppose a gas embargo not because it is technically impossible, but because they think it would cost them too much. The German logic is that a gas embargo may tip Germany into a recession. But it is Russia’s invasion that risks tipping the whole world into a recession.

What could the EU do right now?

The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) recommends that the EU should:

- end all fossil fuel purchases from Russia to strengthen the effect of the sanctions and help end the war.

- end trans-shipments of Russian fossil fuels to third parties.

- institute tariffs on imports from Russia, which would encourage buyers not to purchase from Russia whenever possible, and curb the price paid to Russian suppliers on spot markets.

- create a plan to replace Russian fossil fuels with clean (non-fossil) energy, energy

efficiency, and energy savings measures as soon as possible.

Are these recommendations realistic?

The recommendation to transition to clean energy sources is not realistic in the short term. Approving the construction of new solar energy facilities or wind farms often takes years, replacing gas-powered electricity power plants cannot be done overnight.

But ending all purchases of Russian oil within 2-3 months – instead of 6 months – is realistic for almost all EU countries. A gas embargo will be costly but it is realistic. Ending trans-shipments should be relatively easy to legislate. Instituting tariffs was actually suggested by the Polish Prime Minister a few days ago and was previously suggested by the US Treasury Secretary and others.

In addition to these measures, EU countries could support radical energy conservation measures in order to slightly reduce the need for energy imports in the first instance. One could add mandatory curbs on energy use in the public sector, for example, by reducing the number of hours that street lights are switched on at night, and offer new public grants for insulation of family homes – to be spent before the coming winter.

What is missing is the political will in many countries. This is why European citizens must help bring about a policy change more quickly.

Related:

- Hungary can switch to non-Russian oil in less than a year, energy expert claims

- The scope of the EU energy dependence on Moscow and practical ways out

- US slaps embargo on Russian oil and gas. Will Europe follow suit?

- Activists block Germany-Poland highway, сall on EU to stop trade with Russia

- Academic publishers continue “business as usual” in Russia

- French companies continue doing business as usual in Russia