The results of the February 27 referendum claimed 65.16% support for the changes in the Belarusian constitution, strengthening Lukashenka’s hold over the country and shedding Belarus’s neutral and non-nuclear status. This came as no surprise, given the dictator’s history with election fraud.

Just a few days later, Lukashenka appears to officially join the war against Ukraine, with reports of Belarusian troops moving to Chernihiv Oblast.

So how and why did Lukashenka allow virtual occupation of his own country, and aided an attempt of conquering another?

Playing both sides

Unlike his early years, the past decade or so of Lukashenka’s rule has been characterized by a cautious foreign policy. Motivated by economic benefits and the fears of losing independence to Moscow, Belarus’s leader carefully played off both the West and the East.

Belarus remained closely tied to its eastern neighbor through structures like the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), and most importantly, the Union State of Russia and Belarus.

But Lukashenka made sure not to put all of his stocks into the Kremlin. Russian leadership was not happy about his refusal to recognize South Ossetia or Abkhazia.

Similarly, when the Russian aggression against Ukraine began in 2014, he did not formally recognize Crimea as Russian territory. Instead, he tried to position himself as a mediator between the West, Kyiv, and Moscow.

As late as 2019, the dictator of Belarus still advocated for closer ties with both the EU and NATO, while pushing against the Kremlin’s attempts at deeper integration within the Union State.

Putin grew frustrated with Lukashenka, but he rightly judged that the 2020 Belarus presidential elections can become a watershed moment. The country was plagued with economic problems and civil liberties were heavily repressed. This made its president deeply unpopular.

Even before the elections, the Kremlin worked on undermining Lukashenka’s position, possibly hoping to replace him with somebody more loyal.

Arrests of presidential candidates and overt electoral fraud sent hundreds of thousands of Belarusians into the streets. Neither they nor the West recognized Lukashenka’s “victory” as legitimate, voicing their support for his challenger Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya.

Isolated from the West and abandoned by his own people, in a truly Faustian manner Lukashenka decided to sell Belarus’s independence for saving his position. He asked Moscow for help.

Putin saw the chance. A $1.5 billion loan was provided to Lukashenka, and the Kremlin announced that Russian security officers are ready to help suppress the protests. With Moscow at his back, Belarus’s dictator survived the attempted revolution through mass repressions and torture.

The new constitution

In 2021, Lukashenka revealed planned changes to the Belarusian constitution, reportedly to answer the calls for reform. In reality, the revision was pushed forward by Russia, which provided inspiration with its own 2020 constitutional amendments.

The new rules set a two-term limit for the presidential office. However, all the changes would come into effect only after the current officials’ end of term. This means that in 2025, Lukashenka could run for two new terms, allowing him to stay president until 2035.

In a clear move against exiled oppositionists, Belarusians who resided abroad during the past 20 years are not allowed to run.

An ex-president will automatically receive a seat in the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly, with the possibility of becoming its chairman. The People’s Assembly is a state body parallel to the National Assembly (the parliament of Belarus), hosting representatives from all the sectors of the government and business.

Not coincidentally, the proposed changes strengthen the power of the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly. It can approve further constitutional changes, draft laws, appoint judges, select members of the Central Election Commission, and has great sway over economic, security and foreign policies. Its chair is given the right to impeach the standing president.

If Lukashenka were to become the head of the People’s Assembly, he can remain the de facto

leader even after the end of his presidency in 2035.

Silent occupation of Belarus

Putin found a new appreciation for the more submissive Lukashenka. The dictator of Belarus proved himself a useful tool in hybrid warfare against the West, mainly by orchestrating the 2021 refugee crisis.

To ensure Lukashenka’s loyalty, several more articles in the constitution had to be changed.

Namely, the segments about Belarusian neutrality and non-nuclear status disappeared. In a bitter irony, the revised paragraph merely stated that Belarus will not allow military action against a foreign country from its own territory.

In September 2021, Lukashenka flew to Moscow to discuss closer cooperation within the Union State. Two months later, a new military doctrine was adopted, preparing deeper integration between the Russian and the Belarusian armed forces.

The same month, Lukashenka told Kiselov he is willing to host Russian nuclear weaponry and recognized the “legality” of the occupation of Crimea.

On February 10, 2022, weeks before the constitutional referendum and amidst the Russian buildup at Ukraine’s borders, the Allied Resolve drills kicked off, bringing 30,000 Russian troops onto the Belarusian territory.

Given the new “relationship” between Minsk and Moscow, it became clear that Russian troops' presence is nothing short of occupation. Despite the dismay of the local population and protests of the exiled opposition, the Belarusian government announced the Russian troops will stay “as long as needed.”

Stepping stone for Ukraine

As the current events reveal, the timing of the military drills was no coincidence. In fact, Putin planned to use the same troops to capture Belarus and Ukraine in a single stroke.

The presence of the Russian military ensured the constitutional changes went as the Kremlin wished them to. With its puppet government backed by the Russian military, the fate of Belarus would be decisively tied to the Russian orbit.

Then there was nothing stopping Moscow from using Belarus against Ukraine.

First, Lukashenka allowed Russian troops and missiles to attack Ukraine from the territory of Belarus.

Now, according to the most recent reports

, on March 1 Lukashenka finally decided to fully join Russia’s war, sending his troops to Chernihiv.

The decision to join the conflict likely resulted from the Kremlin’s pressure and went against Lukashenka’s better judgment. It remains to be seen what will be the extent of the Belarusian involvement and how effective will it be.

Some experts cast doubt on the effectiveness of the Belarusian military. Many of its 50,000 troops are conscripts, and due to Lukashenka’s cautious foreign policy, the soldiers have little-to-none real combat experience. Furthermore, Russian attempts at modernizing Belarus’s Soviet-era equipment have not made significant strides.

Motivation to fight against Ukrainians also comes into question. Given the cases of low morale among the Russian soldiers, one can assume the Belarusian army will suffer similar problems.

Direct participation in the war will definitely mean stronger sanctions against Belarus and costs of war in life and material.

Trending Now

However, the continuous threat Belarus poses is by allowing Russia to pour more and more reinforcements into Ukraine, by providing a safe rear to the Russian military, and by hosting rockets and shells that fall on its southern neighbor.

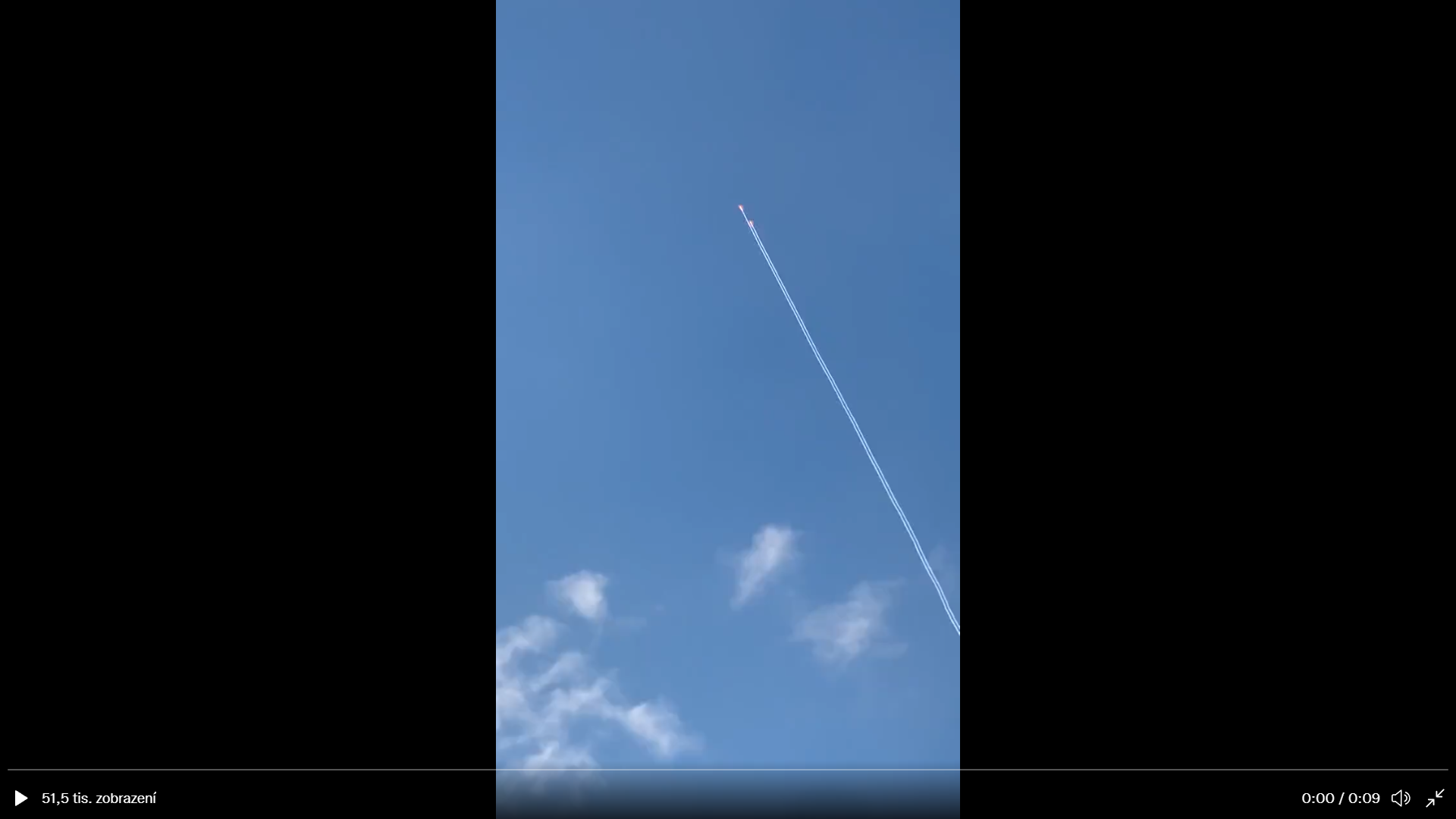

Iskander missiles fired from the vicinity of Mozyr, Belarus. Source

Lukashenka’s actions allowed Chernobyl to be taken, and Kyiv to be bombed and attacked in the very first days of the conflict. His decision could put nuclear warheads close not only to Ukraine’s northern border but also to NATO countries. And now, he ordered Belarusians to fight a nation, with which they have never been at war.

His actions made Belarus a stepping stone for Putin’s dream of a renewed Russian imperium.

Related:

- The year that changed Belarus: where Lukashenka’s regime stands after a year of protests

- Belarus could become Russia’s Northern Ireland if Putin pushes for unity, Grashchenko says

- Belarusian propaganda machine launches attacks to support regime’s instrumentalization of migrants