Four German political experts and politicians describe the scope of the Russian financial and media influence in Germany. They further explain the German policy not to provide weapons to Ukraine and name the German-Ukrainian cultural and political bridges that should be built.

The many disagreements between Germany and Ukraine on foreign policy include Germany's refusal to supply defensive weapons to Ukraine, amid a growing threat of a Russian invasion, as well as blocking access for Ukraine to purchase weapons from NATO; Germany's active promotion of Nord Stream 2 pipeline that finances Putin's regime as well as a refusal to recognize Holodomor, the Soviet man-made famine in Ukraine, as genocide. The main question is how to build a German-Ukrainian understanding.

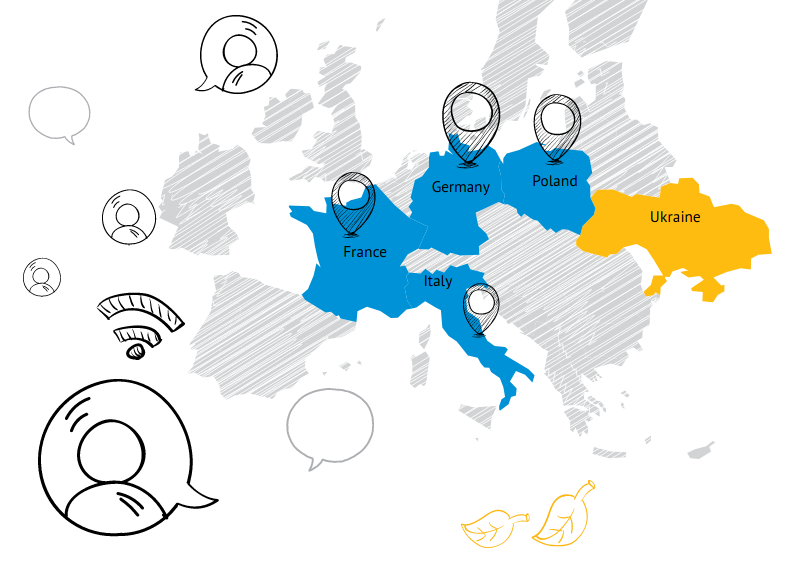

The participants in this interview series are:

- Marieluise Beck served as an MP from The Greens until 2017. She is a member of the German-Ukrainian Parliamentary Friendship Groups and co-founder of the Zentrum Liberale Moderne think-tank.

- Susanne Spahn is a political scientist, historian, and journalist. Her research interests are Russia’s foreign policy in the post-Soviet area, Russian information policy, and the Russian-speaking community in Germany. Spahn’s work includes six research reports on Russian media in Germany.

- Hannes Adomeit is a German political scientist focusing on foreign policy, security and defense, and transatlantic perspectives in Europe. He is a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Security Policy at Kiel University.

- Andreas Umland is a political scientist studying contemporary Russian and Ukrainian history as well as regime transitions. He is a Senior Expert at the Ukrainian Institute for the Future in Kyiv as well as a Research Fellow at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs in Stockholm.

The strategy of Russian media in Germany is to address the dissatisfied

Marieluise Beck adds that Russian media propaganda has a long history in Germany, whereas the mild government response of providing facts and figures has only recently begun.

Spahn: The most popular Russian media in Germany is Russia Today (RT) and Sputnik news agency (SNA). The audience of the RT has developed very dynamically. During the elections last year there were 1.4 million users on the main social media platform.

It’s very interesting to look at the strategy of Russian media in Germany. They present themselves as an alternative to the mainstream. And their image is to show the truth. They accuse the mainstream media of hiding the truth saying that we, the Russian state media, show the truth. It really works successfully. We have many people in Germany who are tired of the corona restrictions, who have lost trust in our mainstream media, and now many people are really attracted to Russian state media.

RT editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan in her 2013 interview to Lenta.ru explained herself that the strategy of RT is to address the discontent and dissatisfied people in western societies. RT and SNA also present themselves as leaders of so-called alternative media.

Currently, I am working on a project with Berlin-based think tank Zentrum Liberale Moderne, and you see that RT Germany is the leader among alternative media. Their funding is EUR 30 million a year.

There is a high presence of Germans who lobby Russian interests and are also very present in the media. I’m talking first of all about former chancellor Schroeder. Apart from that, influential people support the Russian narrative, for example, the head of the German-Russian forum Matthias Platzeck and journalist and author of many books Gabriele Krone-Schmalz. They have a huge influence on German public opinion.

Let’s compare with the Ukrainian presence. For example, we had a discussion on our national broadcaster just on 6 February 2022 concerning “the Ukrainian conflict” as it is called, not “Russian conflict” but “Ukrainian conflict.” There were three politicians who were reluctant to assist Ukraine by delivering weapons, including those for self-defense. We had one American journalist and historian Anne Appelbaum who was speaking in favor of Ukrainian interests and finally we had the Ukrainian Ambassador in Berlin.

In total, only one person represented Ukraine directly, but even this is progress. Compared to 2014, you could hardly find any Ukrainian representative on TV. There were only representatives of Russia and "Russia-understanders" talking about Ukraine and shaping public opinion.

73 East Europe experts call on Germany to “fundamentally correct” Russia policy

Beck: Russian propaganda has been part of public life in Germany for as long as I can think. So the anti-nuclear weapon movement was partially supported by DDR and Russian money and propaganda in order to weaken Western military capacities.

Since Maidan and 2014, Russian efforts to influence German citizens have become much more vivid, especially using the possibilities of social media. Germany was very careful not to intervene in the basic right to freedom of information. It took too long until we finally started at least offering facts and figures in order to counter the Russian propaganda.

Many German journalists are still reluctant or afraid to research and write about Russian influence in the German economy and in lobbyism

A proposal to establish a fact-finding committee in the Bundestag receives little support as long as the SPD is in government. According to Susanne Spahn,

journalists in Germany can be easily sued if they disclose Russian influence, as was the case with Catherine Belton.

Beck: Our media is the main driver in revealing the Russian subversive structures in economy and politics. Unfortunately, we know way too little about Russian money flow into our markets. This would need much more research capacities in the public sector and it would have to be part of an international strategy.

DIE ZEIT or some other big newspaper just revealed a big network which you must call Schröder - Gazprom connection in Germany. It is very big, Gazprom has been systematically creating a network since Schroeder left the chancellor’s office with outgoing and active political representatives who got well-paid jobs in the energy business. They mainly belong to the SPD but you also have CDU guys, who, for example, lost their mandate and thus were easy to get.

There has been a proposal to set up a fact-finding committee in the Bundestag. But of course, as long as the SPD is in the government they will block it.

Spahn: Generally I must say that knowledge about Russian political influence and lobbyism in Germany is not very well known because this is a very sensitive question, you can be sued very easily. An example is Catherine Belton and her book Putin's People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took On the West. She works in the UK. She debunked this Russian network and then she was sued by Russian oligarch Abramovich.

A well-known example of Russian lobbyism in Germany is the Schroeder network, including former deputy chancellor Sigmar Gabriel. It is well-known that Schroeder started the Nord Stream 1 project when he was in office. After 2005, Schroeder got high-ranking positions in the Russian company Rosneft and the pipeline companies Nord Stream 1 and 2.

There were some publications in Tagesspiegel: how Schroeder together with Gazprom head Miller were meeting with ministers Gabriel and Brigitte Zypries in order to promote the project Nord Stream 2 – that was in 2015-2017, despite the annexation of Crimea. Schroeder regularly commented on Germany’s Russian policy, and the public did not know about his lobbyism for Gazprom for a long time.

“Historical guilt” as an excuse for not supplying weapons to Ukraine is “false rationalization” because the same guilt argument is not applied to Ukrainians. Germans still fear Russia

Marieluise Beck and Susanne Spahn tell about the lack of knowledge among Germans about Holodomor as well as about Ukrainians who suffered from both Russian and German totalitarian systems. It is an essential task for teachers of history and researchers to break the false identification of Soviet people with Russians and build a more nuanced picture. The main lesson from WWII on which all speakers agree should be “no longer support an appeasement policy towards the aggressor country,” rather than overemphasize the importance of dialogue.

Adomeit: It is of course absolutely ridiculous when we talk about historical responsibility that the vast majority of those who suffered casualties during WWII, proportionally to the population, is higher in Ukraine and Belarus than in Russia.

So, we have just the case of false rationalization by those trying to appease Russia.

Many people have the idea, that I consider just a false rationalization, that anything enhancing deterrence, including weapons supplies is, literally, “destabilizing,” “provocative,” and escalation. This goes back to the time of NATO maneuvers in Poland called Anaconda.

Steinmeier said that war-saber-rattling does not help to defuse the situation.

Why we need a discussion about Germany’s historical responsibility toward Ukraine

Beck: The reason for the majority in Germany opposing the delivery of weapons to Ukraine is a fear of Russia and the wish not to be drawn into a military conflict. I think that there is a hidden memory in many families of the horrible suffering in the two world wars in the last century. So the “never again” is very strong.

Also, Russia obviously managed to turn the feeling of historical guilt towards the Russia of today. It is not well known enough anymore, that the beginning of WWII was planned by the two European totalitarian systems: Hitler Germany and Stalin's Soviet Union, and that they divided Poland between themselves. There is not enough awareness to say again and again: The Wehrmacht attacked the Soviet Union and this means the territory of the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine of today.

There is not enough knowledge that the forced laborers who were forced to work in Germany were not Russians alone but millions of Ukrainians and other nationalities.

There is not enough knowledge about the Holodomor. Even the term is very unknown until now and I think we need more documentaries, more movies like Agnieszka, Holland's great movie about that tragedy.

Hunger for Truth: Documentary about Canadian journalist who was first to report about Holodomor

Spahn: Many Germans feel guilt because of the second WW. I think this is not very logical because they feel guilt only in relation to Russia but not to Ukraine, Belarus, or the Baltic countries, although they also had millions of victims. Unfortunately, the majority of Germans feel this guilt exclusively in relation to Russia. Our experts and journalists should spread more information about Ukraine.

Many Germans, when they think about the Soviet Union, think about Russia. For them, Russia is identical to the USSR, even though the majority knows that it is not accurate. For example, when elderly Germans speak about WWII, they say “Russians are coming,” not Ukrainians or Belarusians.

During the war, we had many workers in Germany, the so-called Ostarbeiters. Now people know many of them are from Ukraine but they still say these people are Russians.

The main message that is currently in Germany’s heads is “no war again” and “no participation of Germany in a war again.” This is the main thinking that has been supported since the end of WWII. Now things change and international challenges also change, Germans should adapt their thinking to the new reality. This is also the task for history teachers and experts in history to draw different conclusions.

German weapons are not especially important for Ukraine, but what is important is to unblock supplies from other countries

Adomeit: This idea of weapons deliveries is actually the very opposite of being provocative and dangerous. Not delivering weapons increases the risk of a Russian invasion.

73 East Europe experts call on Germany to “fundamentally correct” Russia policy

Why I believe it is so important that Germany delivers weapons is precisely because Germany is one of the most important countries that has been so favorable towards Russia. If the German government would now adopt a tough policy towards this gang of criminals in Moscow, it would really deter Putin. But unfortunately, this isn’t happening.

Umland: This decision about weapons is not related specifically to the conflict between Russia and Ukraine but it is a decades-old official policy of Germany not to export weapons to countries that are in active conflict. I think this discussion that has developed is unfortunate because it demands Germany change its general policy, its foreign affairs philosophy. It may be wrong, I don’t agree with this policy but this whole tradition is unrelated to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

It is interpreted in Ukraine as an anti-Ukrainian and pro-Russian decision, but it is not. I think this is a superficial debate going on right now which will not end well. It simply polarizes relations between Germany and Ukraine and it also polarizes journalists, experts, and analysts within Germany.

German weapons are not so important but it is certainly necessary that Germany lifts its ban on weapons’ purchases by Ukraine. The weapons that Estonia wanted to give Ukraine contained German technology. I think the story with the NATO procurement agency and that Germany blocks the purchase of weapons by Ukraine from other countries is really Germany's mistake.

Germany blocks Ukraine’s arms purchase from NATO as unofficial arms embargo on Ukraine continues

Germany’s “special relationship” with Russia can be partially explained by common cultural elements; the Ukrainian argument for Germany could be that Putin suppresses Russian culture as well

Beck:

There is still some deep-rooted emotional feeling of being made “out of the same dough” with Russians. Russia has Dostoevsky, Germany has Goethe. Catherine the Great was a German princess. Our sentiments, our feeling of “being deep-rooted with our deep souls” is something that is seemingly being our connection. The opposite to Americans with their modernism, jokes, and always optimistic way of life.

Umland: I think a special relationship has existed between Germany and Russia for a very long period of time. It was even before this pacifist approach to international affairs was adopted in Germany...

The Ukrainian argument could be that current rulers of Russia came out of the old Soviet repressive organs, the KGB. These former KGB officers are not only repressing Ukrainian, Georgian, Estonian national identity and so on; but also the KGB repressed Russian culture, the Russian Orthodox Church, science, and philosophy. They do not represent the Russian nation. That could be an argument that will work. Russian intellectual life was very influenced by Germany and vice versa. That is why it is hard for contemporary Germany to just stop these special relations with Russia.

Hannes: It is rooted deeply in this basic conceptual approach that the SPD, but not only SPD, has attempted to pursue since the collapse of the USSR. It is encapsulated in these slogans that by interlinking we can achieve change through trade and human contacts.

Of course, this hasn't worked at all. The occupation of Crimea and intervention into eastern Ukraine occurred when the German and Russian economic relations were at their height. This idea hasn’t worked, but it is typically human that if you have strong ideas and strong convictions in your head, you don’t want to admit that you were wrong. You lean to this conception despite the cognitive dissonance that is produced.

This idea worked with France because it was supported by both sides, by the French government as well. The principle of this reconciliation is right if we have both parties pulling in the same direction. But if we have one party pulling in one direction and the other in the exact opposite direction then of course it can’t work.

Demands to sanction Putin’s German agents of influence as Chancellor Scholtz visits Ukraine

Germany’s reluctance to be in full alliance with the Anglo-Saxon world still plays its role in contemporary support for Russia

Spahn: It is questionable whether Germany is still a reliable partner anymore in the EU and also for the US because the majority of politicians support appeasement policy. In the summer of last year, head of the Greens Robert Habeck and Greens MP Viola von Cramon traveled to Ukraine and stated that Germany should supply Ukraine with defensive weapons. And then, of course, a public discussion started in Germany. And the overwhelming reaction was: no, no deliveries.

I think this is bad for Germany. It leads to Germany's international isolation. It turns out we have these special relations with Russia that I think Germany should stop this policy. In the majority of cases in history, it was bad for the world. We had the second World War and the Hitler-Stalin pact. Our policy should support democracies in Eastern Europe more actively, especially Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova which are partially occupied by Russia.

Nord Stream 2 also leads to German isolation and to our dependence on Russia. Currently, Germany gets 55% of its gas from Russian resources. When we start the pipeline this share will even increase which is a bad development for Germany. We should diversify our supplies and import more liquid gas as Poland has done.

Germans like to say that the US is against Nord Stream 2 because it wants to sell its own liquid gas. This is what German politicians often say. This is misleading, I think. It is not only the US. We have many producers of gas worldwide.

Realistically Ukraine will not join NATO soon, but bilateral relations with allies is the best approach at present

Umland: Unfortunately there is a very small chance that Ukraine will join NATO. I’m afraid Ukraine will be able to only enter NATO when it no longer needs it. The problem is that it is not NATO that decides on the membership, but each of the 30 member states has to agree.

I think the emphasis on NATO membership was a mistake of both Poroshenko and Zelenskyy. What should have been done is to develop a bilateral relationship with Poland, with Romania, with the US, with the UK, Intermarium idea. This is, I think, the primary way to go. If it was the real perspective, I would say that Ukraine should join NATO today. But unfortunately, it is not, and the best way is to develop bilateral relations with those countries that support Ukraine.

Cheap airlines and human contacts are the best way to develop German-Ukrainian bridges

Beck: There is not enough knowledge about Ukraine becoming more and more like a modern Western society. There has not been enough tourism to Ukraine yet so that our people see that Ukraine is Europe and belongs to Europe.

Although being a member of the Greens I can only quote Karl Schlögel, one of the best-known historians in Eastern Europe. He says that the best way to make people know each other is by flying with cheap airlines. And it is true: if young people can fly at low cost for a weekend trip to Odesa or Lviv or the Carpathians (where even I have never had time to go) -- we will start knowing each other, losing prejudice and gaining normality as Europeans. Lets pupils exchange for one or two weeks, students take part in the Erasmus program. It is about meeting, meeting, meeting…

Related:

- “Germany bears a special responsibility for European security”: Ukrainian Jews appeal to Chancellor Olaf Scholz

- Scholz in Kyiv confirms Germany won’t arm Ukraine, stays mum on Nord Stream 2

- Euromaidan, rebirth of the Ukrainian nation, and the German debate on Ukraine’s national identity

- Germany exports dual-use products to Russia despite EU sanctions, beefing up Russian military

- Why we need a discussion about Germany’s historical responsibility toward Ukraine

- Echoes of Nagorny Karabakh. Why Germany is worried about Ukraine’s drones in the Donbas war

- Why does Germany refuse to export arms to Ukraine?

- Demands to sanction Putin’s German agents of influence as Chancellor Scholtz visits Ukraine

- 73 East Europe experts call on Germany to “fundamentally correct” Russia policy