In the third part of the four-part series, 30 Years of Freedom, ten speakers from Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, Russia, and the Baltics elaborated on how their countries built their national identities and unified their nations after the disintegration of the USSR, key events for nation-building, and how they reappraised their historical narratives.

All four parts are based on the comments of our speakers, including quotes from their published essays:

- Part One. Demolishing monuments not enough to destroy post-Soviet nostalgia, but property rights help | 30 Years of Freedom, p.1

- Part Two. The post-Soviet oligarchy and how it shaped national state politics | 30 Years of Freedom, p.2

- Part Three. The end of the Soviet Man: How ex-USSR states forged their national identities | 30 Years of Freedom, p.3

- Part Four. How to stop Russian wars in post-Soviet states? | 30 Years of Freedom, p.4

In 1920, when hopes were high for the creation of an independent Ukraine, Georgia, Belarus, and Baltic states, the national independence struggles were mostly ended with occupation by the USSR. The Baltic states, Moldova, and western Ukraine were engulfed by the “Prison of Nations” a bit later, in 1945, the end of WWII.

During the times of the USSR, communist authorities constructed an artificial "Soviet identity." In the post-WWII period, its cornerstone was the myth of the Great Patriotic War which attempted to coalesce differing nationalities around the myth of the Great Victory of the Soviet people. At the same, the secret Nazi-Soviet Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was smearing national resistance movements that fought against the Soviets during WWII.

In 1991, at the downfall of the Soviet Union, the national identity and consciousness of the nascent states were still unclear. As sociologists concur, the majority of people in post-Soviet states were disoriented when the USSR fell apart.

Roughly a third identified themselves merely as residents of a certain town or region. Another third named different identifications, including “Soviet (wo)man” – a popular terminology of the time. Only the last third considered themselves primarily as citizens of the new Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, and so on.

The issue was further clouded by Soviet demographic policy. On the one hand, it created proxy and quasi-folk national identities, and on the other tried to mix or resettle populations and assimilate them into the Russian world. This largely explains why in the 1990s, the Russian language was popular and people were diffident about the simulacra of their national cultures.

Today things are changing as integral, modern national cultures evolve.

Central to many discussions is the deconstruction of the Great Patriotic War myth: viewing the events of WWII not through a victorious, but a tragic lens, as well as reassessing the role of insurgents who fought against the Red Army.

As our speakers outline in detail, Ukrainians, Moldovans, Belarusians, and Georgians have undergone a difficult process of reassessing WWII and rediscovering key events of their history, in the journey to reach their unique formula for consensus – albeit still fragile.

Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia tried different ways to deal with strong Russian opposition and prevent the Russification of their states – a process also relevant for other post-Soviet states.

In today’s Russia, the opposition seeks to revive the idea of a democratic Russia and construct a political model for it, contrary to Putin’s narrative of reviving the empire.

Belarus

Shreibman: Belarusians' appreciation of their national identity is not similar to that of Ukrainians' because it is not centered on the issue of language, nor on the issue of national symbols or ethnocultural issues. Belarusian nationalism is sometimes described as civic, i.e. centered on statehood. It is a very distinctive kind of civic nationalism.Belarusian nationalism is sometimes described as civic, i.e., centered on statehood

According to the polls, Belarusians don’t support merging with Russia, for example. These numbers are in the single digits – five, six, seven percent, depending on how you ask the question. An additional 12-15% might support deeper integration with Russia, in some sort of EU structure. Everyone else supports preserving independence.

Independence has become a value. It was not a quick process, but a very gradual one. The majority of Belarusians are pro-Russian in that we are friendly towards Russians as a nation and support an economic union with Russia, unlike Ukrainians, for example. At the same time, there is a similar appreciation of independence, as you see in Ukraine. Let’s not understand these words as black and white, rather as the reality at the ground level. Belarusians are not in favor of any kind of concessions in terms of their sovereignty.

Speaking Russian in these circumstances is not a contradiction to Belarusians. They see it possibly in the same way as the Irish see their independence from the UK. Belarusians have their separate identity which is important to them – the Belarusian identity for the Belarusians.

Ben: How do people in Belarus perceive WWII?

The polls that I have seen demonstrate a couple of things. First of all, victory in the Second World War and Victory Day is still the key event in historical memory. Belarusians are less tolerant towards the renaming of streets, relocation of Soviet monuments, and other decommunization proposals. This reflects a very important myth about the Great Patriotic War, as many still call it in Belarus. Every fourth Belarusian died in the Second World War, and everybody has relatives who suffered – that’s why it is the cornerstone of national memory.Every fourth Belarusian died in the Second World War

I’m not aware of any regional differences. Generally, Belarus is quite a homogeneous country. It is different from Ukraine in this regard. There are very small differences in terms of support for Lukashenka. In the east of Belarus, it’s slightly higher but not by much. However, there are no significant differences among Belarusians on these historic issues.

Khadanovich: Belarusians also have their Golden Age, and this is the Grand Duchy of Lithuania when Belarusians, or those who are now called Belarusians (then named differently) were an important part. Then, the language of the ruling elite, the language of literature, and the language of legal documents – such as the Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania – was a language that can be called, with a certain approximation, Old Belarusian. I think that Ukrainians also see a certain role in the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

It was a state in which several nations coexisted. It just so happened that modern Lithuanian historians acted early and interpreted their legacy with respect to their international image first. Belarusians seemed to find themselves homeless orphans.

Regarding WWII, the Soviet myth also tried to erase everything that was anti-Soviet. All non-Soviet partisans were taboo and were not mentioned. Belarusians who developed Belarusian culture during the Nazi occupation were unequivocally called collaborators.

Our national white-red-white flag is banned by Lukashenka. This is the flag under which people protest today. In fact, the colors of our flag and its Coat of Arms are the same as those of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, albeit the horse’s tail is depicted somewhat differently.

The God Almighty accompanied by the scenes of Belarusian protests, one of the unofficial anthems of free Belarus:

Moldova

Erizanu: There is no difference between the Moldovan and Romanian languages – officially we don’t have a Moldovan language. We have the state language, but obviously it is Romanian. The president for instance says “Romanian language,” not “Moldovan language.” The Moldovan language is something the Soviets invented to prevent national sentiment.

I think I’m both a Romanian and Moldovan writer, and I also have both citizenships. Definitely, over a million people have this double citizenship.We have moved on from a sentimental discourse between Romania and Moldova to a stage when close identity is manifested in actual pragmatic support

The discussion about political unification with Romania is now promoted only by a few small political parties and the media. Some of the parties are quite controversial – not really aiming to unite with Romania, but perhaps just aiming to divide society. It seems to me that right now at the forefront of peoples’ political ambitions and needs is the reformation of the state into a functioning democratic state that serves its citizens.

Our ties have become closer with Romania since Maia Sandu was elected Moldovan president in 2020. Romania has provided a lot of help to Moldova; for example, restoring kindergartens across the country, the National Art Museum, and so on. So it feels like we have moved on from a sentimental discourse between Romania and Moldova to a stage when history and close identity – or even the same identity – is manifested in actual pragmatic support.

Soviet authorities in Moldova tried to reinforce Moldovan identity as distinct from Romanian identity. I think our cultural opposition to the regime during Soviet times was much linked to these identity issues. For example, writers in the 1960s wanted to go back to writing Romanian in the Latin alphabet and some were declined by publishers because of their position on this matter.

In the late 1980s, that kind of spirit revived once again and the independence movement was led by cultural figures – by writers in particular, as well as vocalists, and so on. They heralded the things we shared with Romanians and had in common with them prior to forced Russification by the Soviets.

On the other hand, beyond these kinds of movements – which were called national liberation movements. We had some artists who tried to find their freedom of expression and how to pursue their art without openly opposing the regime, but neither supporting it – just having their way. Sometimes they were supported by the authorities, at other times they were suppressed and had their opportunities dismissed.

They tried to create their own islands of freedom. For instance, Valentina Rusu Ciobanu, a painter who is now 100 years old.

In the 1980s, literary events gathered thousands of people. They were very influential, but a few years later this changed, and now I would say that culture is quite marginalized, especially economically. There is no systematic support for independent culture from the state – no strong cultural policy.

Negura: During Perestroika, national emancipation came to the fore of public discourse. All people declared and demanded a better position for nationals in the Soviet system, as well as a better standing for the national language. The key demands of the new political forces were national and nationalist, and not economic or ideological.

One of the highly controlled – and even forbidden – topics that became popular during Perestroika was everything related to nationalism and nation; for example, Bessarabia, having been part of Romania in the interwar period. These topics were quite widely discussed during 1988-1991. The same was true about modernist authors, be they Romanian or international.

Strangely, many people who became active nationalists in the late 1980s had collaborated relatively well with the Soviet establishment in the 1970s. They wrote poetry about Lenin and the party, and they were quite prominent in the literary establishment, such as the Writers’ Union. But in the 1990s, the nationalists, whom they had joined, failed to keep power. Subsequently, the topic of unification with Romania dwindled. These developments were discussed a little in some political circles but did not become a real public issue.

Ben: Can we look at Moldovan history as part of Romanian history in terms of nation-building?

Yes, Moldova and Romania had a complicated relationship, especially during the interwar period from 1918 to 1940 when Moldovan Bessarabia was part of Romania. Added to this is perhaps the war period itself when Ion Antonescu was in power. Antonescu was quite proto-fascist at that time and went so far as to instigate a Holocaust in Bessarabia and Transnistria. But beyond this episode of WWII, Romania ruled Bessarabia for 22 years.In the interwar period, Romania helped develop the intellectual elite of Moldova, which was important for nation-building

This may not be considered very long, but enough for the nation-building process in Moldova. However, this nation-building was without Transnistria, because Transnistria at that time was a Soviet republic within Ukraine – an autonomous Soviet republic within the territory of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

In the interwar period, Romania helped develop the intellectual elite of Moldova. Those 22 years were very important in Moldova’s nation-building process.

However, I don’t mean to overemphasize the importance of Romania when it comes to Bessarabia. Yes, Moldova had a 22-year history with Romania, but we also had close to a century under the Russian Empire and then a further 50 years under the Soviet Union.

Even though it was the Romanian authorities who started mass education in Moldova, especially in the countryside, they did not complete the process.

Just to give you one example, in the late 1930s almost half of our population were still illiterate. In this, I would say, lies a large part of the failure of the Romanian modernization effort, which is why the Soviets succeeded (perhaps only slightly more than Romania) in promoting a Soviet nation-building agenda. In other words, encouraging a Moldovan identity apart from that of Romanians.

Ben: As you mentioned, during WWII Moldova was part of Romania. How does this fact impact the contemporary perception of WWII? Was it a victory or occupation when the Soviets arrived?

We have two big extremes in the spectrum of public discourse about WWII. At one end is the argument that is pro-Russian, promoting WWII only as a victory against fascism. At the other end is a discourse that interprets these events in terms of occupation by the Soviets. In everyday life, we have a kind of banal nationalism with people placing the insignia for Georgievskaya lentochka on their cars, and at the same time other people placing the traditional Romanian tricolor flags on their cars.

But at the same time between these extremes, we have a silent majority that manages to cooperate in everyday life without major conflicts. So, I would say that WWII is not a strong issue in our society. Many people in Moldova, in Chisinau, display this Georgievskaya lentochka and nobody pays attention. We don’t have a "Crimea" yet in our recent history, which could explain the absence of aggressive sentiment.

Ben: What would you recommend to read, or otherwise, learn about Moldova?

Starting with literature, I would recommend Tatiana Țîbuleac who wrote a series of novels. She lives now in Paris but was a TV journalist in Moldova during the 2000s. She still writes in Romanian and has translated many works into other languages, such as French and English.

I would also recommend Iulian Ciocan who writes about regular life under the Soviets; specifically, the late Soviet period. He also explores the post-1991 transition, leading into the present. He is a type of chronicler, depicting everyday life.

Georgia

Ideological, ethno-cultural divisions and the WWII narrative are relatively not important for contemporary Georgians. Conversely, both ethno-cultural divisions and the WWII narrative were actively exploited by the USSR – and currently the Kremlin – to divide Georgia and justify the occupation of its regions.

Jishkariani: WWII is not discussed as much in today’s Georgia as it is in Russia and Ukraine. Of course, the population of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic participated in WWII and Georgia received many refugees. But on the territory of Georgia there was no Nazi occupation and no military operations.WWII was not as important for Georgia as it was for Russia

For Georgians, WWII is an event that affected people, but it was not as important as it was for Russia, where WWII is the core of the new Russian identity. WWII is discussed in Georgia annually on only two days: the 8th and 9th of May. And the discussion is predominantly about when to celebrate, on the 8th or 9th.

Yet, there is great reverence for soldiers who fought in the war, because it was a tragedy for young people to have experienced these terrible events. In almost every village, you can find small monuments with names of soldiers who left the village and never returned. These monuments were erected during Soviet days, but sometimes when they have deteriorated local villagers gather to restore them.

Another difficult question in Georgian history is how to consider those who fought with the Nazis. Like Ukrainian battalions within the Nazi army, there were also Georgian battalions. The question is whether we need to equate them with the Red Army soldiers. Both of them believe they were struggling for Georgia.

Regarding contemporary Georgian political identity, one may say that independence from Russia – cultural and political – is more important than the anti-Soviet or decommunization policies. The USSR was considered through the lens of struggling against Russian domination.The USSR was considered through the lens of struggling against Russian domination

At the same time, the USSR had its clear ethnic policy with the aim of constructing a Georgian nation, while demanding their policies be imposed vis a vis Ossetians and Abkhazians [ethnic groups in Soviet Georgia at times recognized as autonomous regions -ed.]. We have to understand that constructing nations was a process – the Georgian nation was constructed, as were other nations, and now this process continues.

When the collapse of the Soviet state was imminent – already knocking on the door – the administrative policy, the language policy, and the national policy could no longer continue in the old way. The problem started in the 1980s, during the Georgian nationalist movements, when it became impossible to find a place for other ethnic groups within a Georgia-centered movement. This was not only a problem of the Georgian movement for an independent Georgia. The same problems arose in Armenia with the Azerbaijan minority.

Of course, living in the Soviet Union at times facilitated the creation of those identities, but living without the Soviet Union, you have to solve your own problems. The political elites that were formed under the Soviet Union were absolutely assimilated into the Soviet political system. For them, it was not easy to function with the new realities and new challenges. Today, we do not need revolutionary changes – rather we need work to be conducted with a long-term perspective by real grassroots movements and a new generation of historians.

- Donald Rayfield Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia

- Stephen Jones Socialism in Georgian Colors: The European Road to Social Democracy, 1883–1917

- Ronald Suny The Making of the Georgian Nation

Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia

Voren: I don’t think there is any discussion about whether Lithuania was occupied or not by the Soviets. It was occupied.

Discussion around WWII centers on several other points. One is the issue of the Holocaust. I think the younger generation understands and accepts the role of Lithuanian security battalions in the liquidation of Jews. But Russia tries to use this.

Another is that you cannot deny that for 45 years the country was part of the Soviet Union. You can not just take it out of your history – it’s there. To what extent do you place this fact into your history in an honest fashion? There were many Lithuanians who lived happy lives during the Soviet occupation in Lithuania, not everyone suffered. So yes, it was an occupation, but it should be assessed honestly within the broader picture.

The Netherlands were occupied by Germans for five years, but even there the discussion is that not all Dutch were good and not all Germans were bad. In Lithuania, this is much more complex, and on top of that is the history of 50 years – two full generations.

Policies regarding Russian minority

We in Lithuania, have a relatively small Russian minority, in comparison to Latvia or Estonia – around seven percent. That is why Lithuania was very lax in giving the Russian minority Lithuanian citizenship. Unlike Estonia, where they were required to learn the national language first before they could apply for citizenship.

In Lithuania, it worked the other way – they got their citizenship and started working in jobs where knowledge of Lithuanian was needed. So they learned it, because it was useful for them, not because it was forced. I think this significantly changed the situation, and now Russia is trying to use the Holocaust card in Lithuania, accusing Lithuanians of being bloody fascists who killed all the Jews and so on.

Estonia was very strict in imposing limitations on the large Russian minority for getting Estonian passports. My attitude towards this is quite dualistic. On the one hand, I understand the fear of having too many potential agents within your country. On the other hand, I see that the Lithuanian way to address this by simply granting them citizenship was helpful in making them feel part of the country – not outcasts.

For Lithuanians, being part of Europe is very important because they consider themselves European – they are Europeans by heart. They were part of Europe, but they were grabbed by Russia. It's much more important for them to be part of the European house than for people in the Netherlands, for example. In the Netherlands, you can easily be critical about the EU because you are part of Europe anyway.

Liekis: Latvia and Estonia kept the principle of restitution. All those that were citizens prior to 1940 could get citizenship. People who moved to Latvia or Estonia during Soviet times received residence but not citizenship. The situation changed later, because the requirement to live at least five years in the country, learn the language, and so on, was fulfilled by all those who wished to do so. This is no longer the issue. In Latvia, if I’m not mistaken, there are only 15,000 “stubborn” Russian citizens left, who only have residence status but not citizenship.

But in Lithuania, you had this zero option of granting citizenship for everyone who was already resident.

Among Russians in Lithuania, one-quarter arrived as early as the 18th century. Those people had very different attitudes to everything. They usually did not identify with Moscow and didn’t want anything to do with it. This category, plus a huge group of Russian technically educated specialists, became very well integrated. I think the state should ensure social mobility for people, and then there is a chance for them to find their position within their new world.

We have no discussion about the Russian minority being discriminated against. Yes, we have some state-funded Russian schools, but less than three percent of kids go there. Some subjects are bilingual. However, the Polish schooling system is more extensive than the Russian in Lithuania.

Russia

Zubov: The resolution adopted by PACE in September 2019 is a guidebook to understanding the events at the beginning of WWII. Two destructive regimes, Nazi and Communist, divided Europe in this foul treaty of Molotov-Ribbentrop pact – which led to many enormous crimes, like that of Katyn (mass execution of Polish military officers by the Soviets during World War II -ed.).

Speaking about the end of the war. It could have been different. Instead, Hitler attacked Stalin’s state and Stalin inevitably became an ally of the Entente. The “enemy of your enemy” is at the very least your ally. By the way, the US, unlike France or the UK, never named the USSR as an ally, rather referring to the “common enemy.” After the end of the war, Stalin occupied half of Europe. We can’t say that the French or English occupied the other half because free and democratic states were established in the other half which later freely united to the EU and NATO.

Subsequently, while the whole world celebrated victory over Nazism, the USSR (today Russia) celebrated the empowerment of dictatorship from Korea to East Germany and Albania.

Ben: What would the new counterpoint of Russia’s path forward look like for a democratic Russia?

I would emphasize the example of the US or India. We can also speak about Canada or Switzerland here – the states which unite many ethnicities but maintain democratic regimes.

Each state deposits its positive and negative coins into the common world “piggy bank,” so to speak. So far, Russia has dropped a lot of negative coins into the bank of world ideas and experiences. However, if we build a free and democratic state in Russia, then I think it will be a huge positive investment for the future of the whole of humankind.

A new Russian generation of people younger-than-40 thinks differently today. They are not “Soviet.” The Internet opens the window. So the youth is not Soviet, but they aren’t anything. We have to educate them as well. We, people of the older generation, and I, as a lecturer by profession, try to explain the past to our youth. It’s important not to lie, not to distort facts. This is my function and that of my party.

Ukraine

Hrytsak: Ukrainian identity and the nation’s political pathways have always been under the powerful influence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the era of the Cossacks.

A unique feature of the commonwealth was the tradition of the free election of monarchs and local parliaments. The same was true under the Cossacks who conducted free elections of the hetman leader and other political structures. I’m not saying that this was transmitted directly, but the Cossack myth has encrypted it – the Cossack myth which is the central myth of Ukraine.

The Cossacks are not only about heroism but also political structures, such as self-government and self-organization. The Cossack myth is essentially a myth of the aristocratic democracy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, only rewritten in the Ukrainian style. Simply put, “nothing about us without us.”

I also emphasize language as the criterion of identity. In other words, the Ukrainian language is the religion of Ukraine, and the poet is its prophet. The central place in the Ukrainian national pantheon is occupied not by politicians but by three writers: Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko and Lesia Ukrainka. This tendency was demonstrated in the 20th century by writer Volodymyr Vynnychenko and journalist Symon Petliura – leaders of the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic (1917-1920) which was destroyed by the Bolsheviks. In 1989, poets Ivan Drach and Dmytro Pavlychko headed the Ukrainian Rukh movement, analogous to the Polish Solidarity or Lithuanian Sajudis movements.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, in Independent Ukraine, the new Ukrainian identity has been most actively articulated by leading Ukrainian writers Yuriy Andrukhovych, Oksana Zabuzhko, and literary critic Mykola Riabchuk.

Other Ukrainian intellectuals that emerged in the 20th century based their ideology on the works of Viacheslav Lypynskyi and Ivan Lysiak-Rudnytskyi. Their thinking can best be reduced to the formula: the main difference between Ukraine and Russia is not language or folk culture, but a very different political tradition and a belief in the self-organization of society. The main reason for these differences is that Ukrainian lands, through the mediation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth for many centuries, were part of Western European civilization, from which the relevant political traditions were adopted.

It is easy to see that the distinction between the "literary" and "historical" versions of Ukrainian identity corresponds to the concepts of ethnic and civic nation. The competition between these two models is the most dramatic in the political and cultural life of modern Ukraine.

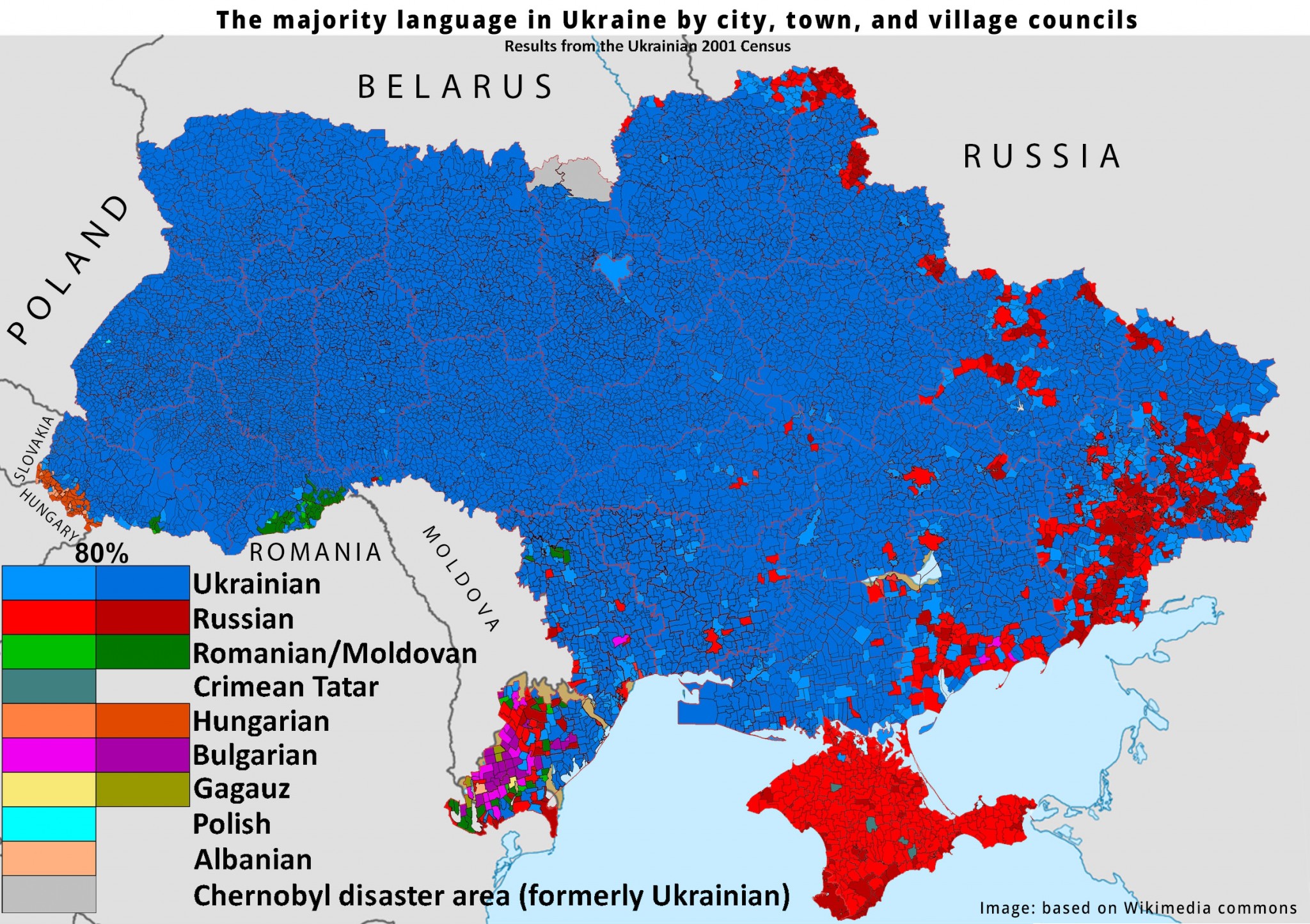

Ben: In post-Soviet Ukraine, the Russian-speaking minority is still strong. How should the presence of the Russian language correlate with Ukrainian identity?

The proposal which was developed earlier by a group of scholars from Germany and Ukraine includes three simple theses: one, Ukrainian is the only state language – period; two, Russian or other languages may have the status of a regional language; but, and this is the third, a status only on the basis of certain procedures.

Procedures, among others, mean that two languages operate equally in those regions that speak both Ukrainian and Russian. This means that all officials must be fluent in two languages and respond by the one addressed to them.

I believe that this thesis was good before the Russian aggression. But after the Russian aggression, Russian became the language of the enemy, so it is clear that the Ukrainian elite will displace it.