The last hiding place of this small Jewish community was identified below Soborna Square in the historic city centre of Lviv, where the team found remnants and evidence of human presence from those dark, tragic days. The diggers announced their sensational discovery on September 8, 2021.

Historical background

During World War II, millions of people were murdered by Nazis across Europe, including Jews, Poles, Ukrainians, Roma, Soviet prisoners of war, intellectuals and the disabled.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union began on June 22, 1941 and on June 30, Nazi troops marched into Lviv, western Ukraine. By the end of November virtually all of Ukraine was under their control.

Nazi authorities moved rapidly to implement their “racial” policies. Over 160,000 Jews lived in the city of Lviv. Most were herded into railway cars and dispatched to extermination camps, such as Auschwitz-Birkenau and Bełżec in Poland. Some were shot or hanged; others starved to death or died from disease, “medical" experiments, or committed suicide. By the end of WWII, less than 1,000 of Lviv’s Jews had survived.

In June, 1943, the Nazis began liquidating the Lviv Ghetto. To escape certain death, many Jews fled into the sewers. Most were found and killed. Of the 70 Jews who descended into the sewage underworld only ten survived, two of them children. Among them was the Chiger family with two children – Krystyna and Pawel, both of whom survived the Holocaust.

In her memoirs - The Girl in the Green Sweater - Krystyna Chiger writes:

“I will never forget the panic that night when we went into the sewer. The Germans… threw grenades through the manhole openings. The noise of the explosions. The darkness. The terrified screams of so many desperate people. It was beyond imagining.

My father disappeared through the hole in the basement floor. I was frozen with fear. He reached up to grab my legs, and I made a small leap into his arms. Then he set me down and turned to grab little Pawel. I was crying and screaming.”

As they stumbled through the dark passages, the group suddenly came upon three sewer workers – Leopold Socha, Stefek Wroblewski and Yuriy Kovaliv. A deal was struck between the Jews and the three men. They would help the Jews if they were paid a certain sum per day. The men brought food and supplies each day. The German police watched everyone and everything, so Yuriy Kovaliv stood guard on the street. The sewer workers brought bread, margarine, onions, and sometimes sausages. They even provided a Jewish prayer book and shared news about the war.

Krystyna Chiger was seven years old at the time, and she later wrote her book The Girl in the Green Sweater. Her father, Ignacy Chiger, also wrote his memoirs, which were later published in Świat w mroku. He describes the sewage system in great detail and how his group moved through the dark, winding tunnels.

'In Darkness' (W ciemności) by Polish filmmaker Agnieszka Holland, released in 2011, tells the story of the Chiger family.

Exploring the sewer conduits of Lviv

Historians Hanna-Melaniya Tychka, aka Handzia and Oleksandr Ivanov from Lviv University joined the team of diggers (Urban Explorer.Lviv). They were both familiar with this story and had attempted several times to follow the underground route taken by the Jews 75 years ago.

When they discovered the site of the final hiding chamber - below Soborna Square - they recruited well-known Lviv digger Andriy Ryshtun and his team, who have been exploring Lviv’s underground Poltva River for many years.

It was thanks to Ignacy Chiger’s memoirs that the group of explorers was able to find its way to the final hiding place.

“We watched the film 'In Darkness', and it seemed a bit surreal, because it wasn’t shot in Lviv. Then, I read Krystyna Chiger’s book, and later – her father’s memoirs, which really helped us a lot. Krystyna was only seven years old at the time, and her memories are more emotional than factual,” recalls Hanna-Melaniya Tychka.

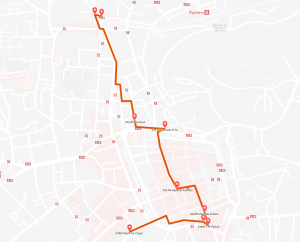

First, the diggers found the place near today’s Chornovola Avenue, where the Jewish fugitives descended into the sewers. They crawled through the sewer passage to the first site mentioned in Chiger’s book. It is located below today’s Dobrobut market, near Hotel Lviv. Krysytyna Chiger gives a chilling description of this underground area:

“There was about a foot of raw sewage at our feet. The smell! The spider webs! Everywhere you looked, there were rats underfoot. And a thick slimy layer of worms, covering the walls, the rocks, the mud.”

Before the war, local women sold fresh bread and produce here [Dobrobut market]. I remembered the smell of the wonderful Kulikowski bread. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine it.”

The Explorer group continued searching for more than a year, moving along sewer conduits to site no.3 (below the church of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, 2 Snizhna Str.), site no.4 (Neptune fountain on Rynok Square), site no.5 (manhole on Serbska Str.) and finally, site no.6 (the so-called “palace”, a vast underground chamber below Soborna Square).

“The walls were wet and covered with mold and cobwebs. Mud covered the ground. Rats were everywhere. Paulina Chiger said - “It’s like a palace. Here we can stay,” writes Krystyna.

The diggers first came across site no.6 - below Soborna Square - in 2019, but it was only in August-September 2021 that they began exploring the underground chamber. They returned several times, recorded everything on photo and video equipment, and finally on September 8, 2021, announced their discovery.

“In the [underground] Poltva River, there are almost no places where people can survive for a longer period of time. There’s water everywhere. This collector sewer could accommodate a large group of people. It was there that we found objects that clearly testified to human presence during the German occupation,” says Andriy Ryshtun.

Searching for evidence of human presence

Ignacy Chiger referred to the chamber as an L-shaped cave with rough stone walls. Another proof of human presence was the broken glass between the stones. Chiger wrote that rats crawled through the cracks in the stones to get to the food stocked on homemade shelves, so the Jews filled the gaps with broken glass. Nails were also driven into the walls, on which clothes or bags of food were hung. In her book, Krystyna Chiger explains:

“… My father figured out how to store food so that those hungry rats wouldn’t be able to eat everything. He made a small shelf where he wanted to keep food that spoilt quickly. But, those rats found this shelf and climbed the walls to get to it. Then Dad had an idea - put some broken glass on the shelf to protect our meager supplies of bread. It worked for a while, but then those clever rats crawled along the bottom of the shelf, clinging to the wood with their tiny claws, and then, finding a crack in the wall, climbed onto the shelf without hurting themselves.”

This finding is indisputable proof that someone actually lived in this tunnel.

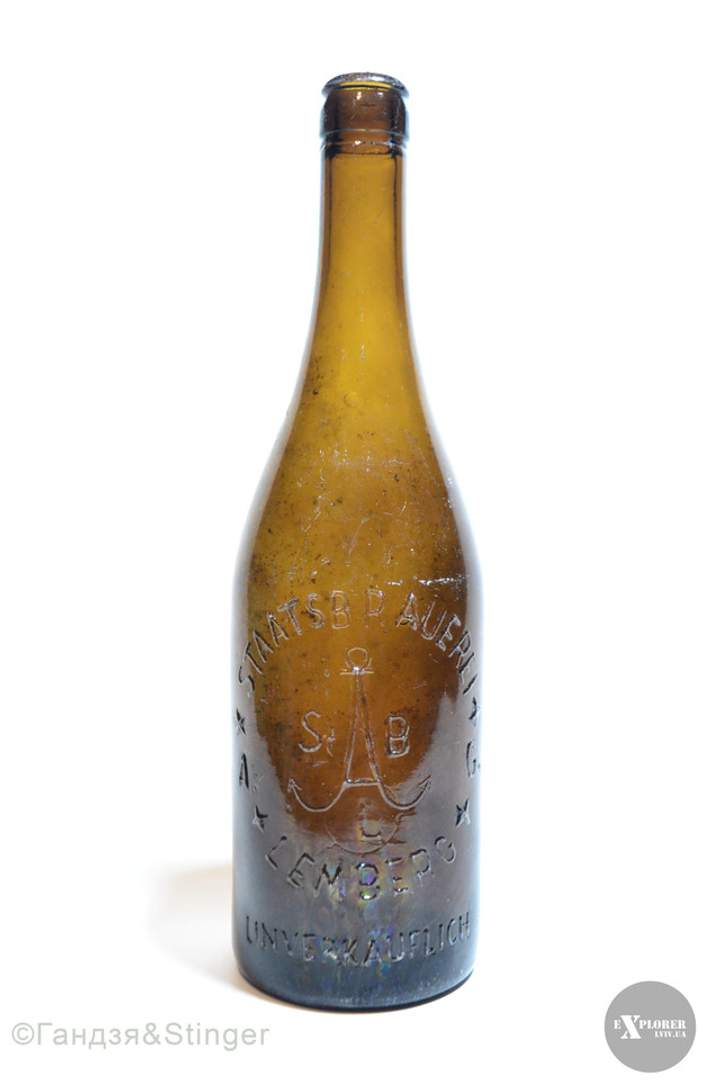

Another surpriseing discovery was a bottle of Lviv beer with an inscription in German - Staatsbrauerei Lemberg Unverkauflich (Lviv State Brewery, not for sale). Experts confirmed that such bottles were produced during the years of German occupation.

In his book, Ignacy Chiger mentions that his group joined the three sewer workers in joint celebrations of Christian holidays. In fact, Hanna-Melaniya Tychka discovered a small Easter lamb figure, which in the Polish Catholic tradition is made of solid cast plaster and used to decorate the festive easter table. Chiger also mentions that when they no longer had anything to give in return, the three communal workers fed them for free.

The diggers’ biggest find was a flashlight made by the Polish company Elekrtrodyn, which at that time was used by Polish soldiers and police, as well as civilians, including employees working in the sewer systems of Lviv.

“When I first entered the collector sewer, I suddenly had the impression that I’d broken into someone’s private apartment. I didn’t find anything at the beginning, but I had an eerie sense of human presence,” Hanna-Melaniya Tychka recalls.

In his memoirs, Ignacy Chiger writes that they used a Primus stove and kitchen utensils to prepare their food. The group had two Primus stoves – one that they had brought from the ghetto and another delivered to the group by Leopold Socha. One of the women, Genia Weinberg, prepared potato soup for lunch every day.

The escape manhole

Hanna-Melaniya Tychka underlines that the search was difficult due to the stifling air, narrow manholes and passageways.

“But, the main point that confused us all was that, according to Chiger’s recollections, the Jews emerged from their underworld through a manhole situated in a courtyard, 2a Soborna Square. In the 1990s, two diggers were photographed near this manhole, and the photos were published in Krystyna Chiger’s book, so no one doubted that the hiding place was right there. In fact, the large chamber below Soborna Square had a drainage system, so it was impossible to get out of the sewers in that place. Therefore, the group had to crawl to the nearest manhole situated in a courtyard on 2a Soborna,” explains Hanna-Melaniya.

On July 26th, 1944, Soviet forces entered Lviv. Four days later, Leopold Socha ran to a sewer grate on Soborna Square and shouted to the group that they could come out of their hiding place.

“We reached a small courtyard behind a cluster of apartment buildings, where a large crowd had gathered. Socha reached a hand to lift me from the manhole opening, and with his hand he hoisted me toward him in a great hug. He twirled me and I was dizzy with emotion. I could hear clapping and shouts of congratulations, but when I opened my eyes, everything was colored in orange and red.

We were like cavemen, like some band of primal animals, but we were alive!” recalls Krystyna Chiger.

Another country, another life

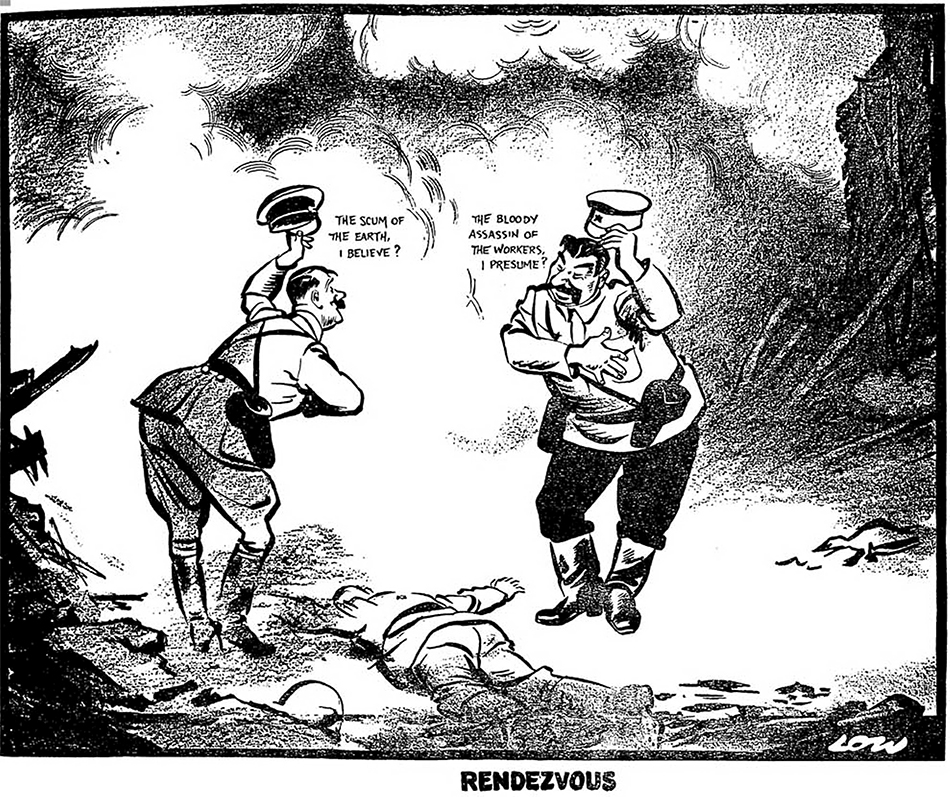

The Soviet occupation of Ukraine did not guarantee freedom to the Jews. Many of them were labeled as “undesirable bourgeois elements” and often placed under police surveillance. In February, 1946, the Chiger family left Lviv because of threats from the NKVD. They lived in Krakow, Poland for twelve years where Ignacy Chiger worked in an office. In 1957, the family moved to Israel.

Ignacy Chiger died in 1975 at 68. Pawel was killed in 1978 at age 39 while serving in the Israeli military. Paulina Chiger passed away in 2000 at age 90. Krystyna left Israel and moved to New York City. Her green sweater, which she wore during her escape, is displayed in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

The State of Israel recognized Leopold Socha, Stefan Wroblewski and their wives as “Righteous Among the Nations.” This prize honours non-Jews who saved the lives of Jews during the Holocaust. One hundred other people in Lviv also received that distinction.

The survivors

Jacob Berestycki - a devout man who held Shabbat services

Ignacy and Paulina Chiger and their children: Pawel and Krystyna

Klara Keler - a young woman whose sister was held at Janowska Camp in Lviv

Mundek Margulies - a comedian

Chaskiel Orenbach - a quiet hard worker, whose brother was murdered

Genia Weinberg - a young pregnant woman, who lost her child

Halina Wind - an intellectual

A new book and a memorial plaque

Olha Lidovska, a representative of the Jewish community and director of the Tracking the Galician Jews Museum (Слідами галицьких євреїв) at the Hesed-Arieh All-Ukrainian Jewish Charitable Foundation, confirms that this place of refuge had never been fully explored, or at least had not been successful. She says that the Centre for Urban History has created a map of the movements of Jews in the sewers of Lviv. After checking the map, Olha Lidovska agreed that this was the most likely hiding place.

“This group of diggers has done something really incredible! Back in the 1990s, there were a lot more investigations, but unfortunately, very little has been accomplished in the past few years. It’s very important that Ukrainian historians and residents of Lviv found this place. The conditions are very difficult down there; the directors of the film refused to shoot there. But, this team of young enthusiasts has closed this chapter once and for all,” says Olha Lidovska.

Based on this discovery, the diggers agreed that the city council should place a memorial plaque near the manhole, and include this site in tourist routes.

“Ideally, you can place a ladder and a light in the manhole so that tourists can climb down and take a look. There’s no water in that underground area,” points out Andriy Ryshtun.

Hanna-Melaniya plans to exhibit these objects in a public space and later donate them to the museum. The items are not valuable, she says, but they have historical and emotional significance. Moreover, they are quite awe-inspiring, especially for the Jewish community of Lviv. She also plans to inform the academic and scientific community about their work, organize further explorations, and possibly write a book about her research.

Testimony by Krystyna Chiger