Before the presidential elections of 2020 in Belarus, observers could not anticipate the massive mobilization against the long-lasting authoritarian ruler. It was believed that Lukashenka will duly win yet another campaign under the usual slogans of stability and order.

However, the president’s poor treatment of the COVID-19 pandemic and his misjudgment of other candidates backfired tremendously: frustrated with the rigged statistics of infected with the COVID-19 and outraged with the dirtiest-ever presidential campaign, the Belarusians swarmed the squares, despite the threats of the authorities.

[boxright]

Further evidence of post-election torture, beatings, and humiliation uncovered in Belarus

[/boxright]

Even more Belarusians poured out into the streets to demand Lukashenka’s resignation after the news about the tortures and brutal beatings in the prisons emerged. The violence documented by passers-by and activists over August 9-12 was on everyone’s lips and led to a political awakening of those on the sidelines.

The collective actions drew worldwide attention due to their scope, the emergence of new narratives, extensive usage of various innovations both in technical terms (such as e.g. Telegram-messenger, Zubr and Voice platforms); and in terms of practices of protest: various art-performances, chains of solidarity, blockage of roads, symbolic appropriation of urban space, etc.

At the same time, the authorities introduced a series of new practices to contain the growing discontent: besides using brutal force, they also arranged multiple pro-government meetings and tried to engage in the symbolic struggle by tearing off historical white-red-white flags and propagating official symbols.

[boxright]

Three months of Belarusian gridlock: do the protesters have a chance?

[/boxright]

However, despite the massive character of the protest actions and the inadequate measures used by the authorities to repress the collective action, the situation, in fact, ended in a stalemate: the political elite seems to be still loyal to Lukashenka, while the scope of the collective actions slowly decreases.

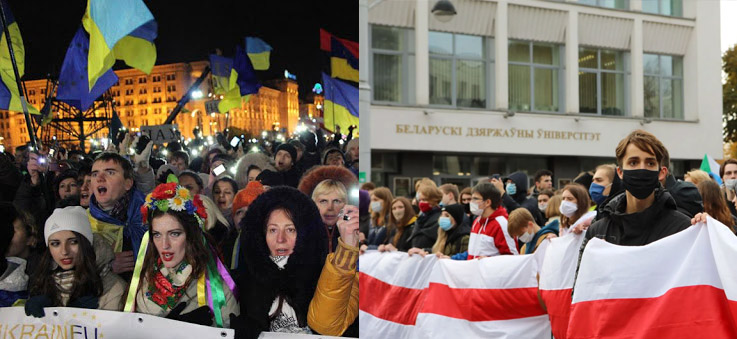

Although largely the world keeps admiring the determination and pronouncedly peaceful character of the Belarusian protest (or the Revolution of Consistency as we term it), certain observers have been calling to a forceful resolution of the situation. In their view, this would have allowed them to avoid unnecessary deaths and tortures and solve the situation rather quickly, referring to the EuroMaidan as a blueprint. Still, in our view, the political and social context in both countries have been radically different, which influenced the trajectories of protest.

In what follows we will enlist the main similarities and differences between the Euromaidan and the Belarusian protest, which, we suggest, defined the specificity of the events in both countries.

What's similar?

Observers see the following similarities in the 2020 Belarusian and 2014 Ukrainian protests:

- The main goal of both revolutions was (and still is in the Belarusian context) to overthrow the current political regime and democratize the public administration system. This goal had determined the peaceful character of protests in both cases.

- At the initial stages of the revolutions, people formed solidarity networks and gathered at the central squares of major cities, where they could voice their demands to the authorities and media (at the later stages protest in Belarus became more decentralized).

- The leaders of both countries (Viktor Yanukovych in Ukraine and Alyaksandr Lukashenka in Belarus) lost mass support due to the ineffective policies and the lack of political will to launch long overdue reforms: the Ukrainian president refused to sign the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement in 2013, while the Belarusian president blatantly ignored the catastrophic situation with the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

- Instead of listening to public demands, the presidents decided to brutally repress the unrest, which resulted in the exacerbation of conflict.

- Russia did its best to support the authorities while condemning the actions of the protesters: this is partially done, first, to prevent similar events from happening within the Russian boundaries, secondly, to continue its general strategy of weakening the leadership in the neighboring countries and increasing their dependency.

- But Russia’s involvement was dissimilar in the two countries: while in Ukraine it annexed part of the territory, launched military action, and created a conflict zone, in Belarus it up until this moment tries to interfere rather indirectly (via strategic advice and propagandist means). Still, the interference in the internal affairs of both states and infringing national sovereignty has decreased Russia’s support in the eyes of both states’ inhabitants.

- Initially, neither Ukrainians not Belarusians saw relations with the EU as a “civilizational choice” or a refusal to maintain relations with Russia. However, aggressive messages which mushroomed in Russian media in support of Yanukovych and then Lukashenka’s regime and in condemnation of the allegedly radical protesters made citizens change their initially neutral stance towards the Eastern neighbor.

- The hot phase of the conflict started after the security forces’ brutal actions against protesters.

Fear, horror, anger, despair, solidarity, apathy, and glee. 100 days of Belarus protests in photos

What's different?

The two protests had the most commonalities in their initial phase. But their subsequent development leads us to see their differences:

[highlight]Varying political and social context[/highlight]

A violated social contract is one of the reasons for the Belarusian protest

One of the problems that led to mass dissatisfaction in Ukraine was the chasm between expectations and real life: a sizeable part of Ukrainians hoped Ukraine will move towards a European future -- to which Yanukovych had his own say.

Belarusians, on the other hand, were for a long time content with authoritarianism as long as life was more or less stable.

However, the situation started decaying as early as in 2011 and went downhill ever since – the poor treatment of COVID-19 and the associated consequences of the pandemic was the last straw that broke the camel’s back. The brutal violence of Lukashenka's regime against the protesters and officials' lies about those cases made the situation worse: now, only the resignation of Lukashenka and his government is considered a viable option for the future of Belarus.

Society in Ukraine was more polarized than in Belarus

Before the Euromaidan, Ukrainian society was divided into what can roughly be classified as the pro-Russian and pro-European camps. While the former preferred close ties with Russia and consequently were less inclined to support Ukraine's national identity, the latter put forward the necessity of national revival and deepened integration with the EU.

Tellingly, after the short period of the pro-European presidency of Yuschshenko, pro-Russian Yanukovych won the elections. Born and raised in Donetsk, a region neighboring Russia, Yanukovych was supported by the pro-Russian part of the population, which is predominantly located in South-Eastern Ukraine.

Belarus never saw such polarization ahead of the 2020 presidential elections. Its geopolitical orientation and national culture have never been a bone of contention. Still, the society got mobilized under national white-red-white flags due to their traditionally “protest” connotations. Also, Lukashenka was universally despised by society as a whole and could hardly have earned bonus points from a certain geographic region.

Russian involvement was different in both cases

[boxright]

[/boxright]

Both Ukrainian and Belarusian protesters were concerned with the possibility of Russian interference in the events because they realized that Russia could try and use the situation of political crisis for reaching its strategic aims. Military assistance from the Russian side in these conditions meant an escalation of the conflict and start of the war. This is why the peaceful character of protests lasted until harsh repressions and brutal actions of the police. The pronounced reluctance of protesters in expressing their geopolitical preferences (choosing rather the integration with the EU, than the relations with Russia) was rather a strategic choice: the main grievances of the protesters were connected to the absence of civil rights, harsh beatings, and persecution. In Ukraine, mass change in the preferences towards European integration occurred after the annexation of Crimea and military intervention in the Donbas region. On the contrary, after four months of the revolution, Belarusians still do not recognize Russia as the main adversary, and a significant part of Belarusians still have a positive perception of Russia.

[highlight]Organization and leadership[/highlight]

The Belarusian protest is leaderless

In Ukraine, opposition activists stood behind the organization and maintenance of the collective actions: they relied on the existing networks of solidarity to mobilize the supporters and arrange public support. The Ukrainian political environment was divided between various influence groups long before the Euromaidan, which allowed for a representation of multiple political ideas and facilitation of the decentralization reform afterward. Given that the opposition occupied about 40% of seats in the parliament, it is not surprising that their voices were pretty resonant, with the popular political leaders playing an active role in the protest itself.

Belarus in this respect is radically different: the Belarusian opposition has never had an opportunity to influence the decision-making process in the country. Not only were elections regularly falsified, but the opposition leaders also had restricted access to media (and hence, no possibilities to weigh in on critical problems and win the votes of the public), and were subjected to co-optation, “soft” and “harsh” repressions.

For nearly 26 years, the authorities successfully implemented the “rule and divide” policy, allowing members of the opposition party to get into the Parliament only once, during the 2016 elections.

That is why the 2020 Belarusian protest has been largely leaderless: presidential candidates and symbolic leaders (Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, Veranika and Valery Tsapkala, Maria Kalesnikava, Viktar Babaryka, etc) were either incarcerated or forced to leave the country. The authorities have been ruthlessly hunting town and arresting any potential leader, which is why “old-style” opposition politicians being almost invisible vis-à-vis the Brownian dynamics of ordinary participants.

The Belarusian protest is decentralized

The success of Euromaidan can be largely attributed to the synchronized and tireless work of various actors who mobilized the supporters and maintained the protest by providing much-needed resources. Also, the tent camp, situated at the central Kyiv square Maidan Nezalezhnosti, was the heart and soul of the protest. In other words, the Ukrainian protest had a clearly defined center, which was supported by the whole country.

Alternatively, the Belarusian protest was fundamentally decentralized, because all the central squares were occupied by a heavy concentration of police. As a result, specific routes for the marches was generated ad hoc: people self-organized proceeding from the generalized plan given by Nexta Telegram-channel (it has over 2 million subscribers, informing about the most vibrant events in the country and allowing to organize the protests). Sometimes instead of moving to the central parts of the city, they simply marched through the urban districts, creating plenty of problems for the police who could not block the protesters.

The strikes are important but not yet massive

For quite a long time Belarusian opposition repeated a mantra: “who wins over the factories, will win the struggle for democracy.” The workers have been deemed Lukashenka’s voters, as he claimed to “save” the factories by not allowing them to be privatized in the mid-90s. This allowed extinguishing the protest potential of workers - they were paid decent salaries, but in exchange obliged to support the governing regime (or just simply stay out of politics).

In a surprise twist, these social strata played a substantial role at the initial stage of the protest. However, the overall involvement was not as significant as was expected given the circumstances (a weakened economy and catastrophic situation with COVID-19). Still, the strikes made it possible to prove that Lukashenka’s support within the working class is not consolidated.

In Ukraine, vice versa, factories were successfully privatized in the 1990s, and the oligarchs owning them pursued various aims within the Euromaidan. This made strikes as a tool for reaching political aims relatively unpopular during the 2013-2014 revolution.

[highlight]The strategy and ideology of the protest[/highlight]

The intensity of the Belarusian protest has been lower while police remain loyal

Euromaidan's dynamic of confrontation between the protesters and law-enforcement agents was considerably more intensive compared to the protests in Belarus.

While the Ukrainian demonstrators blocked buildings, burned tires, and violently responded to attacks of the authorities, the Belarusians have been moderate in their struggle against the police.

In Ukraine, security forces had been less coherent and loyal, media were not controlled by the state, and, more than that, Yanukovych has not been prepared for such a large-scale revolution; as a result, initially he tried to solve the crisis via peaceful means.

Lukashenka, on the contrary, already was aware of the dangers of protest movements, because he closely followed the Euromaidan. He did everything in his power to prevent anything similar from happening in Belarus:

- mobilized available administrative resources and law enforcement agents to prevent large-scale protest actions;

- blocked access to the Internet;

- launched a propagandist campaign against the protesters;

- hampered access to fair information and data after the elections,

-- but he still was not able to stop the protest.

At this moment his power rests upon sheer violence: the salary of riot police was raised manyfold: compared to the average salary ($450), payments to riot police reached up to $1000, depending on the seniority and rank.

In Ukraine, the security forces did not have such a financial motivation to keep the regime of Yanukovych intact. That is why they sided with the people's militia after the conflict was exacerbated. In Belarus, high rewards paid to the police helped Lukashenka to keep the police under complete control.

The Belarusian protest is more cohesive ideologically

The Belarusian protest relies on several main demands:

- the necessity to stop the violence;

- conduct new fair and transparent elections;

- and make Lukashenka resign.

These three claims are simple enough to unite the protesters from various political camps, formulate a clear political agenda shared by the majority of protesters.

Alternatively, the ideology of the Euromaidan has been a mixture of various political preferences (from public reflections on democracy foundations to the vector of strategic movement and the geopolitical orientation of Ukraine), because of the heterogeneous composition of the protest movement.

Conclusion: the Revolution of Consistency is in full swing

In a certain sense, the duality of the Ukrainian Euromaidan proved to be so influential that it determined two trends visible in the trajectory of the Belarusian protest:

- its exemplary peaceful character and longing for large-scale transformations on the one side,

- the brutal repressions from the side of the state on the other side.

The Revolution of Consistency, as we prefer it to call due to the determination, resilience of the protesters, and their pronounced commitment to peaceful means of protest, has fundamentally changed Belarusian society.

This aspiration to destroy the centralized power system and longing towards deep systematic transformations is something that makes the protest similar to the Euromaidan.

In the end, the decentralization reform launched by Ukraine in the post-Euromaidan era was to guarantee that backsliding into authoritarianism is no longer possible.

In this sense, Belarusians have learned the lesson provided to them by their southern neighbors.

Besides using the violence extensively, they also arranged multiple pro-government meetings and tried to engage in a symbolic struggle by tearing off historical white-red-white flags and propagating official symbols. However, the protesters and civic activists responded with a series of conceptual and technical innovations to bypass the impediments posed by the regime: the collective actions were noticeable for their scope, the emergence of new narratives, extensive usage of various innovations both in technical terms (such as e.g. Telegram-messenger, Zubr and Voice platforms); and in terms of practices of protest - various art-performances, chains of solidarity, blockage of roads, symbolic appropriation of urban space, etc.

Despite Lukashenka being “the dead man walking,” and the massive character of the protest actions in Belarus, the situation is still uncertain: the political elite seems to be still loyal to the incumbent, while the scope of the collective actions slowly decreases. However, in the end, the Revolution of Consistency is doomed to success.

This is an adapted version of a text which appeared in the book Let the World Hear, published by Stockholm Free World Forum (Frivärld).

[boxleft]

Dr. Olga Matveieva is head of NGO “Ukrainian Expert Foundation” (Dnipro, Ukraine).

Dr. Olga Matveieva is head of NGO “Ukrainian Expert Foundation” (Dnipro, Ukraine).[/boxleft][boxleft]

Dr. Vasil Navumau is a visiting fellow at the Center for Advanced Internet Studies (Bochum, Germany).

Dr. Vasil Navumau is a visiting fellow at the Center for Advanced Internet Studies (Bochum, Germany).[/boxleft]