It is now three months since Belarusians said they had enough of the rule of the “last dictator in Europe” and rose up against rigged elections. Every day of these three months, Belarusians from all regions and walks of life resisted by holding protests, pickets, rallies, marches, strikes, solidarity chains, and mini-concerts. They defied the threat of criminal prosecution and even death, withstood police torture, and kept hanging up the banned white-red-white flag every time it was torn down.

As the protesters have remained defiant, so has self-proclaimed president Alyaksandr Lukashenka. After a ghastly crackdown in the several days after election day on 9 August, his regime appeared to grow more tolerant of the insubordinate populace, which led to a proliferation of creative protest forms, including multi-hundred-thousand marches, all over the country.

[boxright][/boxright]

Lukashenka, who is widely believed to have stolen the election, was unfazed.

He jailed or expelled all the remaining active opposition, including his challenger Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, viewed by the protesters as the rightful president-elect, and is pushing through changes to the Constitution while again cracking down on dissidents, who he derogates as “terrorists” steered from abroad. At least 17,000 have been detained across the country, with the riot police using stun grenades, rubber bullets, water cannons against the protesters, amid reports of torture in police departments.

From exile, Tsikhanouskaya gave the embattled strongman Lukashenka a deadline of two weeks to resign, put an end to police violence and release political prisoners, warning that he would otherwise face a nationwide strike from 26 October.

Can it force the dictator, who is seemingly unperturbed by EU sanctions against him and his entourage, finally heed the rallying call of the protests, “Leave!”? Or will the dissident nation be pacified into submission?

Students come to the forefront

[boxright]THIS IS THE BELARUSIANS SECOND ATTEMPT AT A STRIKE. THE FIRST ONE TOOK PLACE IN AUGUST:

[/boxright]Wave of strikes sweeps over Belarusian industry on third day of protests against rigged elections

Compared to the first attempt at a strike in August, which was announced by anonymous Telegram channels directing the nascent protest movement, the participation of enterprises is now somewhat lower. That is not surprising given that the authorities had managed to frazzle the August strikerrs through intimidation and threats of layoffs.

On the first day, 26 October, over 255 people were detained at strikes and other protests in the country, according to the human rights organization Viasna. Students in several universities refused to attend lectures and marched in Minsk in protest. Hundreds of small private companies declared Monday a non-working day. Meanwhile, shops and cafes closed their doors, with their owners and employees forming human chains all over Minsk.

Students are increasingly coming to the forefront of resistance. The first university to join the strike was Minsk State University, where 100 students held a “sitting protest,” leading to the administration announcing that mass events will be limited in the following days.

Other universities on strike included the Minsk State Linguistic University, where teachers submitted a strike notice to the university’s chancellor, the Belarusian State Economic University, the State Medical University, and the Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radioelectronics, where approximately 35 employees announced an indefinite strike. Several teachers had resigned, while students held numerous protest actions.

Minsk State Linguistic University teaching staff officially went on strike.Decision was handed over to the dean.They want to make their protest public and to encourage others to join in. Meanwhile Lukashenko demanded to dismiss anyone striking: medics, students, workers etc. pic.twitter.com/ciHBLwwE01

— Franak Viačorka (@franakviacorka) October 27, 2020

At least 138 students and 15 teachers have been expelled as of 3 November. One of these students is Karina Kalinka, who together with three other students was disenrolled from the Academy of Arts for her political stance.

“I was motivated by my conscience and solidarity with people risking their future, going out in the streets,” Karina told Euromaidan Press. After the start of the strike, the management of the university ramped up pressure on the students and teachers critical of the Belarus regime. It seems to be working: one of her teachers did an ideological U-turn and is now loyal to Lukashenka, at least in words.

“I, as an artist, want to live in a free country, where there would be no censorship for media and artists so that anybody could express her opinion without fear of persecution,” Karina explained her motivation.

Censorship permeates Belarusian society, especially the arts. Karina experienced this herself when she and her co-students, one of whom was also expelled, created an art installation criticizing the Belarusian political system, replete with descriptors such as “violence,” “impunity,” “lawlessness,” “violence,” “corruption,” “murder.”

“They closed the door, threatened us with reprimands, locked the auditorium up so no photos would, God forbid, leak into the media. The censorship is very strong when it concerns politics. When it concerns other topics they don’t like, it’s softer — like, go away and don’t show this to anyone.”

Photos: courtesy of the artist

Like many other people of her age, she was not politically active prior to the rigged elections. That has now changed:

“Prior to the protests, we were all divided, did not communicate; now I am witnessing the revival of the Belarusian nationality, everyone starts talking, making friends, incredible things are happening, in my opinion.”

Now, having been expelled, Karina will continue protesting and supporting her striking friends.

Like other expelled students, she is eligible for support from the BySol fund, one of the many funds set up to help striking workers who have been fired. As well, several western universities have set up scholarships for Belarusian students expelled for their political activities.

The teachers who do not give in to political pressure could be dismissed or fired, like it happened to one of the best specialists in the Italian language and culture, Associate Professor Natalia Dulina. After emerging as a strike leader at the Minsk State Linguistic University, she was called upon to voluntarily resign by its management. Upon refusing to do so, she was kidnapped by law enforcement, driven away to a detention center, and given 14 days in jail.

Yana, a 23-year-old teacher of the Polish language at the private Minsk-based Center for Slavic Languages, took part in the strike as well, together with other teachers and students. It lasted one day — the employees and students met to write letters to political prisoners while the Center was put on a “technical pause.” But there’s no major sense from her private school taking part in the strike, she says:

“While small private firms take part in the strike, it won’t reach its goal, unless the strike will grow to the national level, like with Solidarity in Poland, when everything stopped for long.”

The strike was supported by the service sector: dozens of bars and restaurants announced a “technical break” on 26 October. There were closures of markets in Brest and Lida due to strikes, as well as shopping centers.

“The cafes and companies take part in the strike so that those who are afraid of losing their jobs at the factories knew that they are not alone, that we’re not afraid, either; we all take part in the strike and all lose money,” Yana explains.

Hundreds of enterprises and businesses supported Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya's call for National Strike. pic.twitter.com/6TetYAw1E5

— Franak Viačorka (@franakviacorka) October 26, 2020

She and other teachers donate a fraction of their salary to solidarity funds which offer compensations to strikers who were fired for their political position. As of 3 November, these funds have paid $2.7 mn to such people. They include employees from all walks of life across the vast state sector of the Belarusian economy, including 14 artists from the Minsk theater of drama. But factory workers are under the greatest pressure: it is the state-owned factories, preserved from the Soviet era, that fill up the state coffers propping up Lukashenka’s regime.

“It’s sad that they didn’t start striking at the large factories: they had a chance in August [at the first strike], but didn’t start. After several days of threats of dismissal, they returned to work. There are many initiative groups of 5 people who started striking, they were fired and jailed. Unfortunately, you can’t really go out on a strike in our country. The fact that they are being fired doesn’t help the protests grow — others see and decide that it’s better to not join the strike.”

The Belarusian regime finds ways to pressure the private sector strikers as well. The cafes that were on strike on Monday are all being shut down for three months and more, after sudden raids of state sanitary inspection services found such violations as scratches on pots and imperfections in mask-wearing.

Of factory workers

Several medium-sized enterprises attempted to join the movement, but so far, the major players had not joined the fray.

Striking workers were reported at the companies Belarusneft, fertilizer giant Belaruskali, automakers Minsk Automobile Plant (MAZ), MZKT, BelAZ, and Belkommunmash, tractor manufacturer MTZ and appliance maker Atlant, Hrodna Azot, BelarusKali, the Minsk Electro-Technical Plant carried out strikes. No enterprise stopped completely: the strike was limited to separate departments and workers.

According to the latest data from the independent trade union, only 84 state factory workers joined the strike, with the number incrementally growing each day. Nevertheless, this was enough for strikebreakers to be detached to Hrodna Azot, a major nitrogen fertilizer plant. They didn’t help: on 10 November, two departments at the factory stopped working, most likely due to the plant being understaffed because the management keeps firing “problematic” workers.

“The shifts have halved, and it takes at least a year to train a replacement: six months of obligatory internship plus six months of practical work. The higher-ups gave the management two orders which were made public several times: fire all the strikers and keep the plant running. This is an opportunity to test whether it is possible to execute these orders in reality. It isn’t. And it’s only going to get worse,” the strike committee of Hrodna Azot told.

Employees from various large enterprises report that the most active factory workers who take part in solidarity actions are questioned by the management. Leading to fears for their livelihood and curbing the spread of the strike movement, many strikers have been fired.

One of them was Vitaliy, a member of the strike committee of state-owned BelarusKali, the flagman of Belarus’ mining industry which produces 1/6 of the world’s potassium fertilizer.

Only 59 of BelarusKali’s 17,000 workers joined the strike, Vitaliy says, but many more are hesitating and in the meantime hold a so-called “Italian strike” at their workplaces, stalling production by demanding that the management ensures its workers are protected by all safety measures, which are routinely ignored in Belarus.

Funds supported by the Belarusian diaspora help the strikers who are fired, but management tries to discourage recalcitrant workers by issuing premiums and raising wages — a sign that it is panicking, according to the strike participants.

The demands of the strikers remained stable throughout the months of protests:

- to hold real democratic elections without Lukashenka,

- bring the perpetrators of police brutality to responsibility,

- and release the political prisoners.

Lately, the list has been topped up with economic demands, as workers were stripped of many of their guarantees and bonuses, Vitaliy says. He believes that the number of strikers on the state-owned enterprise will grow, leading to falling revenues to the state.

What can the EU do to support the protests of the Belarusian workers? One promising avenue, Vitaliy says, is holding off contracts with state factories while repressions of Lukashenka’s regime are ongoing. One such company is Norwegian Yara International, one of BelarusKali’s largest clients, which has hinted it may drop contracts if the factory management keeps firing strikers:

“Support us… It’s difficult to deal with the regime from inside the country. Our demands are simple — we want economic and trade relations with all the countries of the world, with Russia, Ukraine, the West, we just want a normal life and development. We want to just live in peace and raise our children, but not with this regime. Either we can stop the situation with peaceful strikes, or Lukashenka will shed blood. Nobody needs this.”

What keeps the protests going?

Why did the first strike, launched right after the election, fail? Anton Ruliou, editor at the analytical center Belarus in Focus, explains that it was an emotional reaction to the uncovered monstrous falsifications. It died out because the mandatory “Sectors for ideology” present in all state factories pressured the workers into submission: some were intimidated, some were jailed. But at the same time, the strikers saw that they were in the majority.

The present strike that started on 26 October is the second attempt to set the wheels spinning, and it is better planned: the first time, there were no funds for workers who lost their jobs for expressing their political position. Now they don’t need to worry about losing their income: the funds will keep them afloat until they find another job in the private sector.

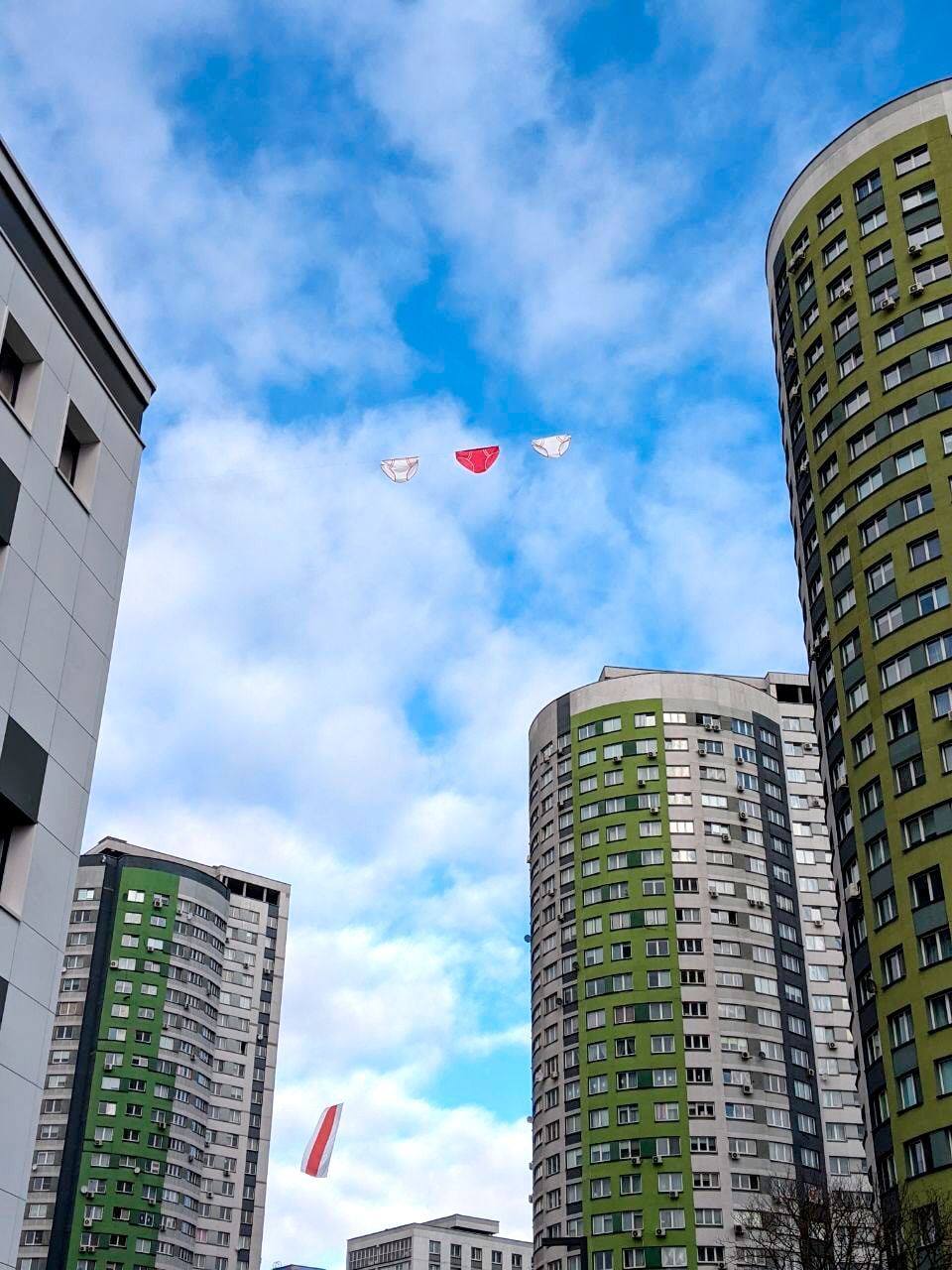

Solidarity and a decentralized, incessant protest is how he describes the events of the last three months. The protest tactics are incredibly diverse. 100,000-200,000-strong Sunday marches, self-organization initiatives such as community get-togethers in the city neighborhoods, solidarity chains, strikes, boycotts of state goods, flyers, stickers, symbols — any form of disobedience chips away at the facade of Lukashenka’s regime. IT workers bring pizza to striking students. Students hold rallies in solidarity with detained medical workers.

Symbols are of special importance. Utility workers are obliged to remove symbols like the banned national white-red-white flag or the Pahonya knight, but they often can’t keep up: whenever one gets removed, three spring up in its place.

“The regime goes into overdrive to extinguish all the fires. For instance, the riot police first chases the participants of the Sunday march and throws stun grenades, and on Monday they again run across the whole city the whole day. They complain that they don’t see their families. It’s important to understand that the regime’s resources are not endless,” Anton Ruliou told Euromaidan Press.

According to him, Interior Minister Karaev claimed that in the regions, he needed to admonish the police so they would repress local protests. The mayors are reluctant to put a clamp on rallies, as in small towns, residents all know each other, and such unpopular measures draw public reprehension.

[boxright][/boxright]

According to a Chatham House study, 85% of protesting Belarusians are ready to take part in them until victory — a year and more.

Do they get tired? Anton says the fatigue is building, but the protesters can take a break from protesting and then return with renewed energy — unlike the riot police. Multi-hundred-thousand Sunday marches, which, however, the regime managed to suppress the last two weeks, are something that gives protesters strength and motivation.

For many protesters, Lukashenka’s savage crackdown right after the elections, on 9-12 August, was an eye-opener: they didn’t imagine that our country was permeated with such atrocities. They were shocked: they don’t want those who started the war against their own people to remain in power. Moreover, if the protests stop, everyone who participated and stood next to them will be caught. Retreating is more dangerous than not retreating.

Constitutional amendments plan wins little support

Critics believe that the Constitutional reform that Lukashenka has peddled since October is but a method to distract the protesters. It’s not working very well, say my Belarusian interlocutors.

“With Lukashenka in charge of the country, no Costitutional reform is possible. The man clearly indicated that power for him equals life, and he isn’t about to give it up. To propose such things, there has to be a certain level of credibility; you can’t suggest such things and simultaneously lie, threaten, and intimidate the protesters. Many times over, Lukashenka said the protesters were high on drugs. They do not trust him at all, and therefore, his proposals aren’t trusted, either,” Anton Ruliou explained.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya called upon Belarusians to vote against Lukashenka’s project. An online poll on the alternative vote count platform Golos revealed that out of the 460,000 participants, 99% voted against adopting Constitutional amendents before new presidential elections would take place.

But there is little detail on what the reform would be about. Despite hints being dropped that they would serve to curb presidential powers, a leaked project document revealed no such plans.

Mr. Ruliou believes that the amendments will be adopted not through a referendum, but through the Belarusian People’s Gathering, consisting of the so-called “best people of the country,” such as the ideological workers at factories or loyal business groups. The protesters will not accept this decision.

“I believe that the Constitutional reform is Lukashenka’s attempt to distract us from our main goal, with which we come out to the streets. We want Lukashenka to leave. We were cheated at the elections, the president is illegitimate,” believes Yana.

What next?

[boxright]AS A RESULT OF THE CRACKDOWN, PROTESTERS ARE NO LONGER ABLE TO HOLD THEIR REGULAR SUNDAY MARCH:

[/boxright]Lukashenka’s crackdown on protesters is increasingly brutal, over 1000 detained this Sunday

Amid the intensifying crackdown, a sense of desperation grows among the protesters. During a dispersed Sunday march in early November, protesters were shot at and beaten by swarms of riot police. Those detained are facing criminal charges of organizing mass unrest, instead of merely participating, which is punishable up to 10 years in jail.

“I personally started being afraid to come out,” Yana shares. “It’s bearable if you get jailed for two weeks, for a month. But three years, 10 years, and criminal charges? The perspectives are totally different.”

What can the world do to support Belarus?

“Don’t forget that the nightmare is growing in Belarus.

Many of my friends were simply kidnapped from their apartments. There are many missing people and many dead bodies found, many more than are officially declared. So when a friend doesn’t pick up his phone, I am scared that we might end up finding him in the forest.

You can help with moral support — I would like to thank the Poles, who mention us during their protests, this really helps. Please support the funds helping refugees — now there are many who flee because of the criminal charges.

Please don’t forget what is happening here; it will continue for a long time. The ideal revolution didn’t happen. Considering that our new Interior Minister [Minister Ivan Kubrakov replaced Yuriy Karaev on 29 October – Ed] is even harsher than the previous one… We know that they will beat our pensioners, shoot at them.

Terrifying things are happening, but it’s valuable that the people are peaceful. There are no firearms from our side, we don’t track them down, don’t ruin their life. But, unfortunately, the story is not mutual,” Yana told.

Read also:

- Why we will cover the protests in Belarus – Editorial

- Meet the 73-year-old granny who became an icon of the protests against Lukashenka

- Policeman who fled Belarus: Lukashenka’s siloviki brainwashed into supporting the regime

- The world’s first Telegram revolution: how social media fuel protests in Belarus

- How Alyaksandr Lukashenka stole the Belarus presidential election