The first proclamation on 22 January 1917 was followed almost immediately by battles with the Bolsheviks to defend that independence. Leading the struggle were the Eastern and Western Ukrainian People’s Republics, headquartered in Lviv and Kyiv, who ultimately were defeated.

In 1941, during WWII, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) declared the establishment of the Ukrainian state, again in Lviv.

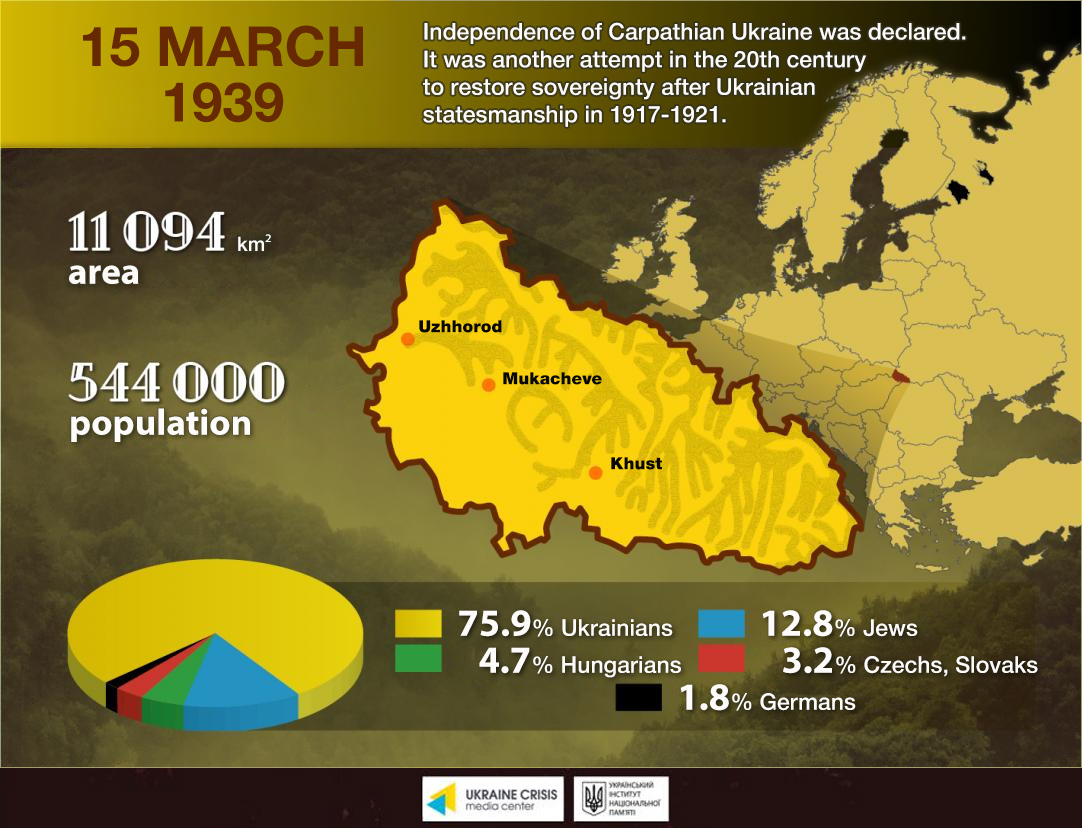

The least known declaration of independence — but equally important — was the creation of an autonomous Carpatho-Ukraine, in the westernmost Transcarpathian region (Zakarpattia) in 1938. Officially proclaimed to be an independent state in the spring of 1939, it was soon overtaken by Hungarian troops. Thus, WWII started for Ukrainian territories, half-a-year before the German and Soviet occupations of Poland.

The documentary, SilverLands: Chronicles of Carpatho-Ukraine 1919-1939, produced by Taras Choliy and Taras Khymych at the Invert Pictures Film Studio, sets out the history of the region. Mixing re-enactments of events with real-life interviews of eyewitnesses, the documentary brings this period of history to life in vivid detail.

Why the history of Carpatho-Ukraine is important for contemporary Ukraine

The Transcarpathian, or Zakarpattia region was isolated from other Ukrainian lands geographically and politically for centuries. It was populated mostly by regionally self-identified groups, such as Lemkos, Hutsuls, and Boikos. As a whole, they were usually grouped together as Ruthenians (Rusyns), and still associated themselves with the Ukrainians of Galicia and central Ukraine. The region was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the end of WWI. In fact, many young Ruthenians were conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian army and forced to serve in the Balkan wars (1912-1913).

In 1919, after the end of the First World War, the Transcarpathian region proclaimed unification with the greater Ukrainian People’s Republic. However, once the republic was occupied by the Soviets and Poland, Transcarpathia became part of Czechoslovakia as a de jure autonomous region, cemented by the Trianon Treaty.

In 1938, after Nazi Germany annexed the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, that country entered into crisis, coming close to falling apart. Attempting to prevent catastrophe, the Czech government granted more rights to Slovaks and Ukrainians. In particular, the autonomy of Transcarpathia — previously only considered as de jure — was implemented. A Ukrainian Government was created in the region, headed by the Uniate priest Avgustyn Voloshyn.

The official term for these Ukrainian autonomous lands was Transcarpathian Rus, however, it was also known as Carpathian Ukraine or Carpatho-Ukraine. On 12 February 1939, the Ukrainian National Union party won 92% of seats in the local parliament.

Within a month, on 13 March, Hungarian troops, supported by the Third Reich and by Poland, began the occupation of Transcarpathian Rus. As Czechoslovakia was not able to defend the autonomous region, the parliament of Transcarpathian Rus with its 92% Ukrainian majority, declared the independence of Carpatho-Ukraine on 15 March and organized a military defense.

The defense was led by the troops of the Carpathian Sich (Carpathian army) created by OUN. The number of Ukrainian troops is estimated to be 4,000, while the Hungarian army was at least 18,000, with many more reserves. With such overwhelming forces, the small Ukrainian republic stood no chance.

Nonetheless, as Mykhailo Kolodzinskyi, a member of the General Staff of the Ukrainian Sich said:

"When there is no longer a reasonable way out of the plight, one must be able to die heroically, so that such a death is a source of strength for younger generations."

As can be seen, the other two attempts for Ukrainian independence in 1917 and 1941 had at least some semblance of hope for success. In the end, the brave battle of the Carpathian Sich was entirely symbolic, having little political but huge historical meaning.

Overall, 430 Ukrainian soldiers died during this short Hungarian-Ukrainian war. In addition, at least 500 captured Ukrainian soldiers were shot by Hungarian troops on the Polish border, and a subsequent terror campaign started against other patriots. Although the official date of the beginning of WWII is 1 September 1939, when Germans invaded Poland, the first true military conflict had already taken place six months earlier, 14-18 March, in Carpathian Ukraine.

How Europe reacted to the proclamation and occupation of Carpatho-Ukraine

During the pre-war period, Hitler’s policy regarding the “Ukrainian issue,” was ambivalent. In 1938 he -- at least -- publicly supported the idea of the “Great Ukraine,” advocating for the disintegration of interwar Poland and the Soviet Union, both of which held Ukrainian territory.

Great Ukraine was a hot topic in the European press at the time. According to Istorychna Pravda, British publications made some 1,000 references to Carpathian Ukraine, from September to December 1938. In December, more than 300 lengthy articles were published about Ukraine in leading French newspapers and magazines, not to mention The New York Times.

Anne O’Hare McCormick was a prominent journalist and was the first woman to receive a Pulitzer Prize for her outstanding work. In 1939, she visited Khust, the capital of Carpatho-Ukraine, as a reporter for The New York Times.

In 1938, many highly-placed European diplomats believed that Hitler planned to support Ukrainian nationalist sentiment to create “Great Ukraine.” In doing so, they upheld the view that this would lead to the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

Thus, on 24 November 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain told French Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet, "The German government apparently expects to begin the destruction of Russia (USSR – ed.) by supporting agitation for an independent Ukraine."

British Prime Minister David Lloyd-George was convinced that the Fuhrer would separate Western Ukraine from Poland, before uniting it with Carpathian Ukraine and Soviet Ukraine. Such a scenario was not considered dangerous for Western Europe.

However, once Hungarian troops occupied Carpatho-Ukraine, hope for support from Nazi Germany for the creation of “Great Ukraine” vanished. Ukrainians found that their aspirations were dashed, with little hope of uniting their lands under their blue and yellow flag -- until 1991.

The documentary SilverLands: Chronicles of Carpatho-Ukraine 1919-1939

The documentary Silverlands was produced in 2012 by Invert Pictures Film Studio and directed by Taras Khymych. Beginning in 2010, Khymych began producing hundreds of musical clips and worked on several historical documentaries. His latest film is a historical drama about Galician King Danylo (1202-1264).

The producer of the film was Taras Choliy, a founder of the Western Ukrainian Historical Research Center and a former director of the Territory of Terror memorial museum, in Lviv. The museum is located in a former prison that experienced mass executions by Soviets during the first days of the Second World War.

Silverlands tells the story of the entire 20 years of Carpatho-Ukraine while under Czechoslovakian rule, with specific attention to the period of independence leading up to the Second World War. It not only depicts the life of Ukrainians in Transcarpathia, but reveals the whole complexity of international relations in central Europe before the war.

Read more:

- Top-6 Soviet World War II myths used by Russia today

- Kyiv during World War II and today: photocollage

- The Ukrainian who saved Krakow from destruction and other little-known WWII heroes

- “Man with a Movie Camera”: One day of a 1920’s Ukrainian city in the early Soviet times

- The Hunger for Truth: Documentary about Canadian journalist who was first to report about Holodomor

- Slovo House — how a special Soviet apartment block for writers became their prison