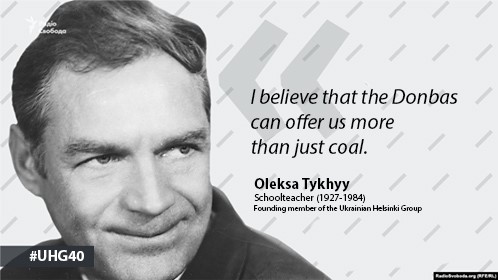

In his article “Reflections on my native Donetsk” (Думки про рідний донецький край, 1972), Oleksa Tykhyy wrote the following:

“Who am I? Why am I here? These questions have always troubled me. I think about them, constantly searching for answers.

Today, here’s what I think:

I am Ukrainian. I am an individual endowed with a certain congeniality, the ability to walk on two legs and speak a distinct language, the ability to create and consume material goods. I am also a Soviet citizen, but, first and foremost, I am a citizen of the world – not in the sense of a bastard cosmopolitan, but as a Ukrainian.

I am but a tiny cell of the vibrant Ukrainian nation. Individual cells die, but the body continues living. Some people die sooner, some later, but the nation lives on because nations are immortal.”

Tykhyy underlines that Ukrainians must gain their independence through language and culture, and thus take responsibility for their future. But, he is convinced that without a good education and knowledge of the world through world classics (not just those recognized by the Soviet regime), as well as travels and new ideas, it is impossible for a nation to achieve esteem, status and recognition.

Village intellectual and teacher

Oleksa Tykhyy was born in the village of Yizhivka, Donetsk Oblast on January 27, 1927. Thanks to his academic abilities, he was able to attend the Faculty of Philosophy at Moscow University.

Even then, at the age of 21, he almost went to prison for criticizing controlled, non-alternative elections in the USSR.

After his studies, Tykhyy worked as a village teacher, teaching Ukrainian children “how to do good, how to raise their material and cultural level, how to search for the truth, and how to fight for justice, dignity and civil responsibility”, applying the old wisdom: “Man lives not by bread alone”.

Oleksa Tykhyy declared that the state cannot dictate the language of communication, or how to spend leisure time, what books to read and what interests to pursue. Moreover, the Komsomol and Soviet taboos cannot be used to educate independent and responsible individuals. Tykhyy severely criticized Soviet young people and their automated daily life, “glorifying the party, Lenin and communism”.

“Young people need to see living, concrete things; they should have the right and the opportunity to search and find their way in life, their freedom. Sometimes, there may be mistakes and deviations, but this would not be as harmful as their total dependence on elders, when young people are ordered to obey without doubt or hesitation.”

The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: “The Soviet regime has reached a dead end”

More than 20,000 Hungarian protesters were injured during the Budapest uprising against the pro-Soviet policies of the Hungarian government. Soviet army tanks rolled into the capital in order to prevent Hungary from leaving the Soviet sphere of influence. Oleksa Tykhyy publicly criticized the killing of peaceful protesters and wrote a letter stating that “it’s no longer possible to build communism in the Soviet Union”.

For such “anti-Soviet views”, he was sentenced to seven years in a penal colony and five years of imprisonment and sent to the Vladimir prison, commonly known as the Vladimir Central, and then to Dubravlag, Mordovian ASSR.

The court verdict stated the following:

“Oleksa Tykhyy slandered the CPSU and Soviet reality. He justified the actions of Hungarian counter-revolutionaries and rebels, called for the overthrow of the Soviet state.”

“I want my native Donetsk to offer the world more than just football fans…”

After serving his prison term, Oleksa Tykhyy could no longer find a job as a teacher. He worked in libraries in different cities, attended advanced qualification courses, visited historical places, and supported his friends who were imprisoned, writes Vasyl Ovsiyenko, member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, ex-political prisoner, publicist, historian, member of the Kharkiv Human Rights Group.

Oleksa Tykhyy published many articles about the russification of Donetsk Oblast and the need to restore Ukrainian culture, about restoring the Ukrainian language in schools and universities. He opposed any policy of assimilation of ethnic groups. Those who call Russia their Motherland should be ashamed of themselves, he wrote in his Reflections on the Ukrainian Language and Culture in Donetsk Region (Роздумах про українську мову та культуру в Донецькій області).

“How should we understand an individual who lives in Ukraine’s Donetsk region, but claims that Russia is his Motherland? Is he an immigrant or an occupier? How would you look at a Hindu or Canadian citizen who claims that England is his true Motherland (on the grounds that India and Canada are part of the British Commonwealth)?”

Oleksa Tykhyy was against discrimination on the basis of nationality, but stood up for the protection of the Ukrainian language and culture in the Donbas.

“I believe that Donetsk can offer us more than just football fans, Russian engineers, agronomists, doctors and teachers, but also patriotic Ukrainian specialists, Ukrainian poets and writers, Ukrainian composers and actors.”

Oleksa Tykhyy’s views were completely in line with those of other Ukrainian activists and dissidents, who announced the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group on November 9, 1976 to monitor human rights in Ukraine. The founding members included Mykola Rudenko, Oksana Meshko, Oleksandr Berdnyk, Petro Hryhorenko, Ivan Kandyba, Levko Lukianenko, Mykola Matusevych, Myroslav Marynovych, Nina Strokata and Oleksa Tykhyy. Other famous public figures, such as Vasyl Stus, Yuriy Lytvyn, Yosyf Zisels, Mykola Horbal, etc. joined the group in the late seventies. By 1982, most of the members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group had been arrested and sentenced.

“You will live in great agony and not for very long”

It did not take long for the Soviet authorities to start persecuting and punishing the human rights activists. On July 1, 1977, Oleksa Tykhyy was accused of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” and illegal possession of firearms, and sentenced to ten years in a strict regimen camp and five years of internal exile.

According to UHG members, this sentence turned out to be fatal for 50-year-old Tykhyy, whose health and physical well-being had suffered greatly after ten years of incarceration in hard labour camps.

Almost all the political prisoners detained in Mordovian prison camps suffered from some sort of digestive or cardiovascular problems. Tykhyy had a stomach ulcer, but nevertheless, he started a 52-day hunger strike to protest the inhumane conditions of political prisoners.

Oleksa Tykhyy was kept in a small cell. He lay on the damp floor; the mosquitoes feasted on his bare flesh; he weighed no more than 40 kilos. He underwent surgery, but his hernia grew larger, causing more pain and discomfort.

“You will live in great agony and not for very long,” one of the doctors told Tykhyy. Vasyl Ovsiyenko testified that during the following operation, the doctor sewed up Tykhyy’s stomach in the form of an “hourglass”, thus making the digestion process unbearably painful.

The camp authorities were particularly cruel and cynical towards the severely ill dissident, who was regularly deprived of visits from his relatives. However, despite all this brutality and violence, Oleksa Tykhyy never confessed to “his crimes” and never wrote a “note of repentance”.

“It is an heretic that makes the fire, not she that burns in’t” (William Shakespeare, The Winter’s Tale)

In 1980, Oleksa Tykhyy was transferred to a political prison camp in Kuchino. Other members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, including Vasyl Stus, Valeriy Marchenko, Yuriy Lytvyn and Levko Lukianenko, also served their terms there.

Vasyl Ovsiyenko was in the same cell as Tykhyy. He recalls the following moments:

“Oleksa never complained. He had an iron will, and constantly initiated conversations on philosophical topics. One of his favourite topics was pedagogy. He was destined to become an outstanding teacher and scholar, but, instead of working as head of a faculty, he spent most of his life in hard labor camps. Tykhyy clearly understood that the best persons would have to be sacrificed before the nation could be liberated.”

Oleksa Tykhyy was placed in solitary confinement three times for 15 days, which led to further deterioration of his already fragile health. He was transferred to the hospital from which he returned to the cell “looking as if he’s just been lifted from the cross.” wrote Vasyl Stus in his Notes from Daily Camp Life (Таборові записки).

Oleksa Tykhyy died in the prison hospital on May 6, 1984. In memory of their friend, inmates Levko Lukianenko and Vasyl Ovsiyenko declared a hunger strike.

“Oleksa was my best friend. He was an exemplary Ukrainian nationalist with a very generous heart,” said Levko Lukianenko.

In her preface to Oleksa Tykhyy’s book Reflections, published in the US in 1982, Nadiya Svitlichna wrote the following words:

“For many years, Oleksa Tykhy stood burning on the pyre for a single heresy – to be able to state his opinion!”

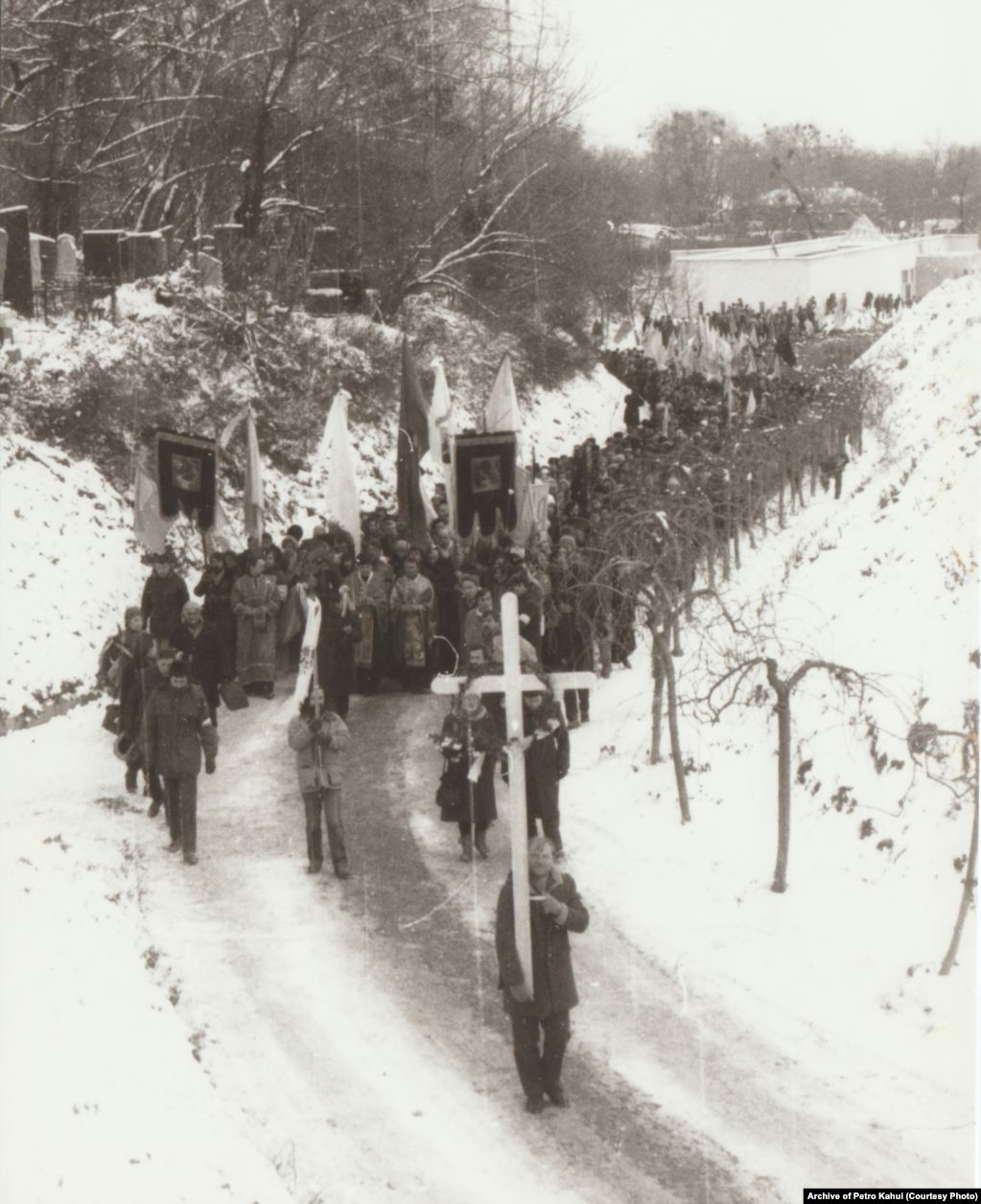

On November 19, 1989, Oleksa Tykhyy, Vasyl Stus and Yuriy Lytvyn were re-buried at Baikovy Cemetery in Kyiv. Despite their fear of the KGB, thousands of Ukrainians thronged the streets of Kyiv and accompanied the funeral procession to the final resting place of the Ukrainian dissidents.

Photo gallery of the re-burial of Oleksa Tykhyy, Vasyl Stus and Yuriy Lytvyn