On 22 December, the Ukrainian President signed changes to the law “On the status of veterans of war, social guarantees for them.” Members of several Ukrainian civil and military organizations of the 20th century were included in the list of veterans who will have social support from the state.

The law targets first of all members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), though dozens of other organizations are also listed as those which fought for the Independence of Ukraine: the Polissian Sich, the Ukrainian People's Revolutionary Army, the Ukrainian military organization etc.

This amendment is the finalization of a long process of recognition of insurgents who fought for the independence of Ukraine and against the Soviet partisans and Army.

Already in 2015, more than 20 Ukrainian organizations of the 20th century were recognized as fighters for the independence of Ukraine in the law “On the legal status and honoring the memory of the fighters for the independence of Ukraine in the XX century.” However, they didn’t get the state social support that Soviet partisans and soldiers have in Ukraine. This changes now, as they are officially considered veterans.

It took 27 years of Ukrainian independence to officially and fully recognize the fighters for Ukrainian independence who fought against Soviet troops and the NKVD secret police, as well as with the Nazis once it became clear that they will not support a Ukrainian State.

But still, despite the official recognition, the discussion about personalities and even some organizations, including OUN, continues. The recent decisions by the council of Lviv Oblast and the Ukrainian parliament regarding the policy of commemoration in 2019 were especially debated, as they glorify Stepan Bandera, the most controversial leader of the OUN(b).

Why are historical topics so complicated?

Generally, history can be viewed on two levels: the level of particular facts and the level of narrative, which stems from the self-perception of a certain community. The second one, of course, should be based on facts, but they’re not so important by themselves. History really matters for us because of the intentions behind certain actions, because of the feelings of those who lived then, and, finally, because we connect ourselves with previous generations into a single community.

The facts are always complicated and gray, showing the entire complexity of life in a certain period, but they never reveal the whole picture, being fragmented, with many parts missing. The narrative is always simplified but tries to show the full picture of a certain epoch in its connection with past and future.

These very short remarks about the philosophy of history are worth mentioning, as facts and narratives are confused quite often in the current political discourse. Some people may take one single fact, blow it up and, appealing to it, condemn the whole narrative, while others may be so frightened by the single fact which contradicts the general narrative that they will try to falsify history. And quarrels erupt.

A recent example worth mentioning is the parliamentary adoption of the list of observances and commemorations for 2019. The fact that Stepan Bandera, a controversial leader of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, was included to the list. And even media were concentrating attention only on his personality.

However, not much was spoken about those 100 famous people who were also at the list or about dozens of important events worth to notice and to write about. The general narrative of Ukrainian way to freedom is overlooked in public discourse while one person becomes a subject for inflammatory disputes.

Thus, let's take a look at the development of historical narrative of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and Ukrainian Insurgent Army (OUN-UPA) and also consider the influence of the most controversial facts - concerning (non)participation of Stepan Bandera and his segment of OUN in Lviv pogrom in 1941, the role of UPA in the Volyn tragedy were many Polish and Ukrainian civilians were killed.

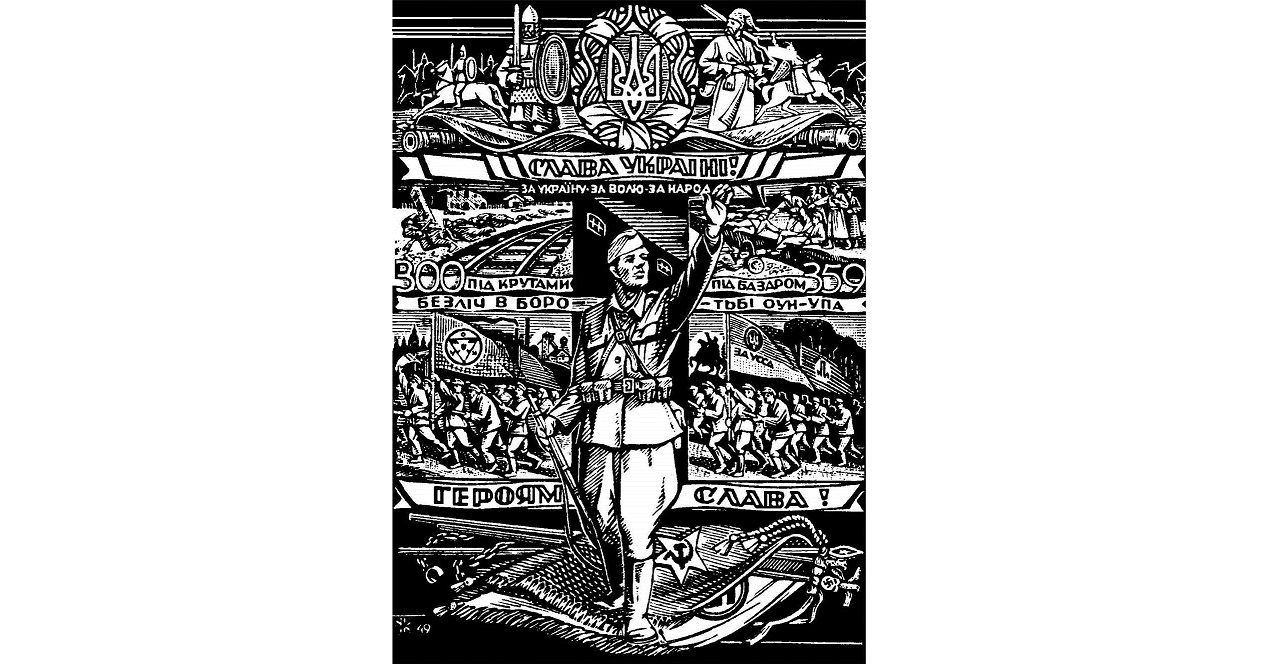

The historical narrative of OUN-UPA

During the period of Ukrainian independence two common narratives of the Second World War were always competing: the Soviet Army and Soviet partisans as those who fought down Nazi Germans and, subsequently, Soviet soldiers portrayed as heroes; and the Ukrainian nationalists, OUN-UPA in particular, who were fighting for the freedom of Ukraine, having some agreements with Germans at the beginning of the War, but later fighting both against Soviet and Nazi armies.

These two narratives were speculated upon at all times and were always used by politicians during elections. The most well-known case is the TV show “Great Ukrainians” which took place in 2008. Ukrainians had to vote for the person whom they perceived as the Greatest Ukrainian (the question for the voting is highly speculative itself because there are different criteria for the greatness in different spheres and professions, which are hardly comparable).

In the final stage of the show, as it was expected, the discussion about Stepan Bandera began. He was holding the 3rd position from the top and had a lot of votes from people of Western Ukraine but strong opponents in the East.

[editorialright]

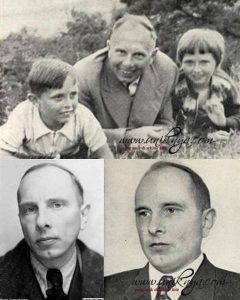

Stepan Bandera was the leader of a radical part of OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) named OUN(b) which split from the initial OUN. He was one of the organizers of the proclamation of the act of restoration of the Ukrainian state in Lviv on 30 June 1941, immediately after the German occupation of the city. Germans didn’t accept this proclamation and arrested Bandera on 5 July.

[/editorialright]

As Borys Bahteiev wrote in 2008 in his analysis of the show, “the society examines not geniuses or heroes, but itself.” Indeed, there were many discussions about facts, stressing one fact or another, but the real discussion was about people’s self-perception and the idea of Ukraine as something either closely affiliated with the Soviet and Russian states or as a fully separate national state.

The eastern part of the country was skeptical about OUN-UPA’s struggle for independence during World War II not because they had a tremendously different version of history, but because that struggle against the Soviet regime was alien for them, especially for those who served in the Red Army. And from the current perspective of 2018, after the war in the east has been ongoing almost for five years, the situation of those pre-war years receives important highlights which were not so visible in 2008.

Behind this telling TV-discussion about whether OUN and UPA are an integral part of Ukrainian history, a more substantial division was visible. And Russia tried to play with it right away.

Actually, at that time 1/3 of Ukrainians were disappointed in Ukraine and, if had such a choice, wouldn't support the Proclamation of independence today, as the sociological polls of the Group “Rating” revealed. This disappointment geographically was perfectly juxtaposed with the strong rejection of OUN-UPA artificially linked to the only image of Bandera, overlooking other leaders and participants of Ukrainian military troops. Stepan Bandera was becoming one of the symbols of Ukrainian internal quarrels between the west and east and Russia actively exploited it since 2009 at least.

For example, in 2009 a propagandist video broadcast in Russia was spread in Ukraine. The video tried to show Bandera as an anti-hero. It used facts, but showed only one side of the personality and omitted context. Russia tried to deepen the already existing split, fueling the radicalization of each part. The same discourse was later fully exploited during the Euromaidan and in the course in the war in Donbas, showing Ukrainians as “banderites” and “fascists.”

Yet, there is an important change in Russia’s messages today, compared to 2008-2009. Now the “fascists,” according to Russian propaganda, are not only the western Ukrainians but the whole country and President Poroshenko himself.

Currently, a trend toward more and more people recognizing the OUN-UPA as freedom fighters is observed all over Ukraine. The official recognition took place against the background of a change in the societal self-perception of Ukrainians and the persons and organization in history with which they affiliate themselves.

As the research of the Rating Group shows, after the beginning of the war in Donbas in 2014, the recognition of OUN-UPA as fighters for the independence of Ukraine has nearly than doubled in Ukraine. For the first time since the country’s independence in 1991, more people support their status as freedom fighters than oppose. Particularly, in Eastern Ukraine, the recognition of OUN-UPA has grown 4 times comparing 2012 and 2017 accordingly to the Rating Group.

Positive attitudes towards the proclamation of Ukrainian independence in 1991 also rose, which indicates that Ukrainians increasingly believe in their own country.

The readiness to fight for the territorial integrity of Ukraine has generally gone up as well, though last year the last number has fallen a bit because people are already tired from war. The current pro-Russian parties in Ukraine try to exploit this mood in their messages “we need peace” without any explanation how do they plan to stop the war in Donbas without capitulating to Russia.

Last but not least, the willingness to have an own independent Ukrainian Orthodox church has risen dramatically among Ukrainians during the last year, accompanying the processes for attaining Church Autocephaly, which culminated in a Unification Council on 15 December 2018.

All in all, despite the efforts of Russian propagandists, Ukrainians become more and more unified in their views on history, church, state and in their readiness to protect their homeland. The clear-cut controversy about the historical narrative of the 20th century is getting smaller, though the divide is still there.

The Volyn tragedy and the recent Bandera controversy: some facts

Despite the growing public support for OUN, UPA, and many other similar entities, the topic remains quite contradictory, especially when it comes to any specific statements about concrete persons or events. During WWII, the region was home to combat actions of both the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and Polish Home Army. This led to tensions. UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) wanted to have reliable support from the inhabitants of the area while Poles were not just indifferent but also hostile to Ukrainians in Volyn. The сhronicle of the very beginning is unclear, though after UPA performed the first “cleansings” the latent mutual hostility arose to armed conflict. Civilian losses were significant because the Home Army together with Polish Shutzmans (policemen) destroyed Ukrainian villages and UPA destroyed Polish ones. The overall deaths are estimated as 16000 among Ukrainians and up to 40000 among Poles, accordingly to Volodymyr Viatrovych who also says that calculation of deaths is the work not yet properly done.

The series of ethnic cleansings called “Volyn massacre” in Polish historiography and “Volyn tragedy” by Ukrainian historians is a part of OUN history which in the last years has become a bone of contention between the two countries.

In Ukraine’s view, it has not been investigated sufficiently to be a foundation for decisive political statements like that of the Polish Sejm on 7 July 2016, which classified the tragic events as a genocide of the Polish people.

Most Ukrainian historians view the series of killings as an international armed conflict, accusing the Polish side of inflating Polish death tolls and drawing attention to killings of Ukrainians in Volyn performed by Polish policemen who had support from German Reichskommissar Erich Koch. The killings of Ukrainians and the destruction of Ukrainian churches in the Holm district began already in 1941. In 1943, accordingly to the Polish policemen’s descriptions of their own work in Volyn, "The village of Podluzhnyi was surrounded and burned, and the inhabitants were shot.”

- Read also: Ethnic Cleansing or Ethnic Cleansings? The Polish-Ukrainian civil war in Galicia-Volhynia

However, this mutual blame game has led to nothing but mutual hostility which is beneficial neither to Ukraine nor to Poland. It may be helpful only for Russia with its attempts to isolate Ukraine from its allies.

That’s the reason why in 2016 Ukrainian intellectuals and former presidents signed an open appeal to the authorities of the Polish state, where they “ask forgiveness and, equally, forgive...” There was similar response received quickly by Polish intellectuals. Nevertheless, almost immediately after, the Polish Parliament voted for the recognition of the Volyn tragedy as a genocide of Polish people.

The Volyn tragedy is probably the most controversial part of the history of OUN-UPA and the ongoing discussion is yet another piece of evidence that it’s time for historians, especially joint Ukrainian-Polish commissions to work on, not for politicians to speak out their opinions.

Bandera the antisemite?

The most recent example of the disputes regarding OUN, this time related to the Jewish massacre in Lviv, is the statement of the Ambassador of the State of Israel in Ukraine Joel Lion. On 13 December he wrote that he “was shocked to hear the decision of the Lviv Oblast declaring 2019 as the year of Stepan Bandera. I cannot understand how the glorification of those directly involved in horrible antisemitic crimes helps fight antisemitism and xenophobia.”

Statements like this have a double meaning for Ukrainians. On the one hand, they call for the critical examination of own history which is, of course, necessary to build their own historical narrative based on proven facts. On the other hand, this particular statement is itself not based on the confirmed facts and serves as a provocation not so much different from Russian provocations. Therefore, it also measures the level of self-control of Ukrainians who should respond abstinently, avoiding groundless conflicts in this case.

Let’s consider this example in details referring to reliable sources.

The verified fact is that the massacre of Jews indeed took part in Lviv after the German occupation on 30 June - 2 July and continued later from 25 to 29 July. However, the role of the OUN as an organization is not proven despite loud conclusions by several researchers, particularly Prof. John-Paul Himka. In his article "The Lviv Pogrom of 1941: The Germans, Ukrainian Nationalists, and the Carnival Crowd," Prof. Himka writes that the Pogrom was mainly organized and performed by Ukrainian police, organized by OUN(b) with a “blessing” from the Germans — a statement which has already leaked to Wikipedia. However, the author neglects the fact that at the time of the first pogrom in June, that police was not yet created. Regarding the second pogrom on July the role of the Ukrainian auxiliary police which numbered much less than one hundred is possible but not well verified. However, the situation becomes even more complicated because at first there were Ukrainian People’s Militia and Ukrainian auxiliary police - the first subordinated to OUN and the second to Germans while both were called “Ukrainian militia” and sometimes the same people belonged to both. Prof. Himka takes facts and quotes out of context many times, faults by overinterpretation and totally neglects that the pogrom was performed by “the population of Lviv” accordingly to German documents and testimonies of witnesses. Organizing of any pogrom on 30 June was against the priorities of OUN and its official documented plans and reports. These are some of the dozens of other arguments which are provided by Ukrainian historian Serhiy Riabenko in his critique of Himka’s reasoning in the long article “On the footsteps of John-Paul Himka’s "Lviv pogrom".

All in all, indeed, many local Lvivians of different nationalities, as well as German Einsatzgruppe C, took part in the Lviv pogrom, but it all appears to resemble more the anger of the crowd, not an action well-planned by any organization. An important fact to which Serhiy Riabenko also appeals is that the number of Jews in the NKVD between 1939-1941 was tremendous. For ordinary people, Russian violence during this two-year occupation of Western Ukraine to a high extent was associated with Jews. This association didn’t correspond to reality: in fact USSR authorities denied “Jewish nationalism” and burned synagogues while the part of Jews in the highest organs of USSR was neither many nor few 18 out of 69. Nevertheless, fueled by German propaganda and by the opening of the Lviv prison where thousands of corpses of people killed by the NKVD were found on 30 June 1941, the public anger towards the Jewish population revealed itself in mass public violence, which was continued later by Germans.

Read also:

- Remains of executed victims found in Lviv’s Prison on Lontskoho Museum

- Lists of NKVD victims killed in mass executions in 1941 published online

In the light of these facts, the statement of the Israeli ambassador is frivolous. The events are not yet analyzed enough by historians to make any ultimate conclusion. They should be studied, but any hasty conclusions lead not to mutual understanding, but to new conflicts.

However, the declaration of 2019 as the year of Stepan Bandera by Lviv Oblast council may not be thoughtful either. Bandera’s history has offered fertile ground for Polish, Russian and also Ukrainian propaganda over the last 70 years. The latter is the case because of the conflict between two wings of OUN, one of which was led by Stepan Bandera, and the other by Andriy Melnyk. Whether Stepan Bandera’s role was helpful for the fight for Ukrainian independence at that time is still disputed.

However, the Ukrainian Institute for the National Memory strongly rejects any accusation of Stepan Bandera as a foolhardy or ambitious person, who strategically didn’t contribute significantly to the Ukrainian struggle. Volodymyr Viatrovych, the head of the Ukrainian Institute for the National Memory, explains that the incorporation of the Ukrainian military organization (1920-1928) in OUN in 1929 is a result of Bandera’s work - one among other examples of his achievements.

The bottom line

It’s highly important for Ukraine that Ukrainians are steadily moving away from Soviet historical narratives and creating their own narrative. This is mirrored in the official policy of the creation of Ukrainian independent church and recognition of the fighters for the independence of Ukraine.

Speaking about the middle of the 20th century, it’s a history of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, where more than 200 000 Ukrainians served from 1941 to 1953. Those people are, without any doubts, worth of commemoration and recognition as fighters for the independence of Ukraine.

However, the history of unique persons, leaders, and political organizations of that time is still to be studied thoroughly. Only between 1917 and 1945, there were more than 20 different Ukrainian organizations which struggled for the independence of Ukraine. It may be disputed which of them used more effective means for the goal, it may be revealed that some of these organizations or persons weren’t so honorable, and then Ukraine will need to face these unpleasant pages in an adult manner and without denialism. However, in no way do some particular facts about particular persons ruin that whole history of thousands of Ukrainians sacrificing their lives for the independence of Ukraine as members of the OUN, UPA, and many other smaller organizations.

Read also:

- Four Myths about Stepan Bandera

- Addressing the great “Jewish Communist” conspiracy

- Historical documents detailing Vistula operation to deport 150,000 Polish Ukrainians now online

- From CIA archives: Stepan Bandera’s 1954 interview to German radio

- Spoiling Ukrainian-Polish relations: next phase in Kremlin’s hybrid war