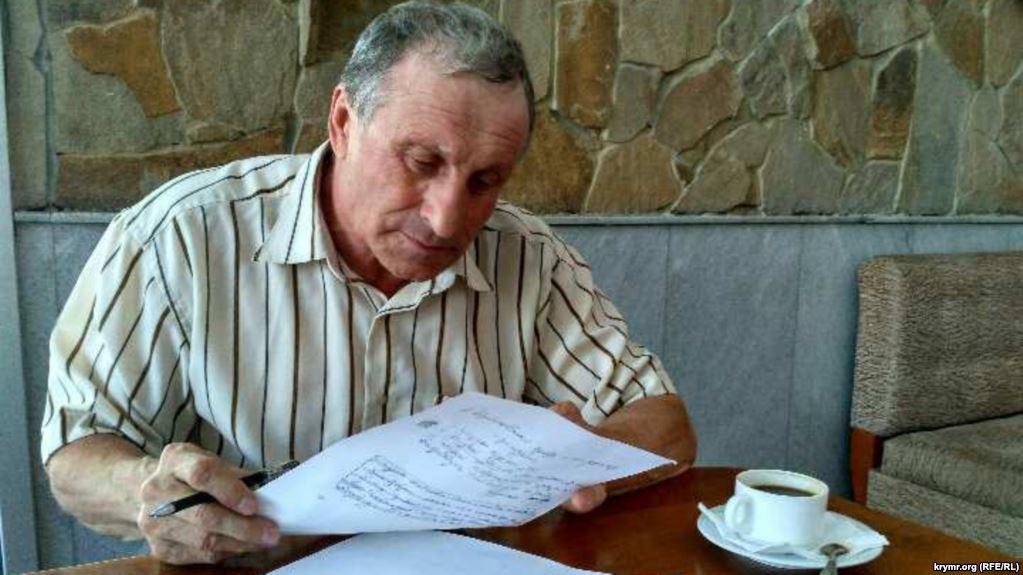

Here we publish the translation of Semena’s last word he delivered in the Moscow-controlled Zheleznodorozhny District Court of Simferopol on 18 September.

Your Honor! Respected Court! All the participants in the trial are witnesses to the fact that I was extremely frank here, spoke honestly and sincerely, the same way as I had written my books and my articles in newspapers, magazines, and the Internet.

By doing so, I relied both on international law and on domestic Russian and Ukrainian legislation and earnestly argued my position in all cases. I think this is exactly how any conscious and law-abiding citizen of any state, Ukraine or Russia in particular, should act. And not only does the state have no legal right to judge him for that, it has no moral right to reproach him, especially as far as it guaranteed both freedom of speech and freedom of opinion in the constitution. Otherwise, this state is doomed.

I do not understand how it is possible to persecute a journalist for a text which is marked as an “opinion” three times, under Article 280.1 [of the Russian Criminal Code devoted to the “public calls for actions violating the territorial integrity” of the Federation], if there is Article 29 of the Constitution specifically dedicated to the right of citizens to an opinion and Article 52 forbidding its illegal restriction, which elevates this concept from the moral to a purely legal level.

Read more: Meet Mykola Semena, the Crimean journalist prosecuted for disagreeing with Putin’s landgrab

And so now I can state that my opinion on the issue of Crimea concurs with the opinion of the most of the world, all the international organizations, and the governments of the vast majority of countries. Moreover, it concurs with the opinion of a large portion of Russian politicians, who openly say today that Crimea belongs to Ukraine even under Russian law.

By no means, therefore, this criminal case is based either on the requirements of the constitution or international law, which is on mandatory for Russia as a member of the UN, or the legislation currently in force in Russia.

What have we seen as a result of the judicial inquest? Obviously, in relation to Crimea, the [Russian] authorities themselves violated international law, their numerous foreign obligations, as well as internal laws, acted contrary to the signed treaties and commitments, although there was a real opportunity to resolve this issue in accordance with international law and without all the complications they received in response.

Now this regime, which is guilty itself, is trying to shift its blame on others, including journalists and me in particular, and trying to make sure that no opinion different from that of the authorities, is published in the country. But this is essentially a violation of the Constitution.

Several times during the investigation, different people offered me to avoid a trial. Perhaps this was a joke, or a provocation, or they wanted to test my mood. But I agreed with my lawyers from the very start—and they can confirm this today—that we would do nothing at odds with the law. It is because of the orderliness that I abandoned this path and went through this trial from the beginning to the end. And I fully agree today with what my esteemed lawyers have said. We did this because we did not want to be identified with a state that itself violates its own laws, that encourages lawlessness and ignores the laws, norms, and rules by which the whole globe, all the countries, and all the world policy live today, in the 21st century.

In order to understand what happened to all of us, between court sessions, I re-read lots of literature telling about the repression in Russia in all periods of her history from the Tsarist period, even from the Decembrists, to the present time. I can say that today, as a result of all the political processes that are going on in Russia, I foresee that, in a very short time, all the currently-repressed will be rehabilitated, and a new powerful stream of prison literature will soon appear in the society. There will be many new Dostoyevskys, new Solzhenitsyns, new Shemyakins, a new Children of the Arbat and a new One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, there will be a new Gulag Archipelago, there will be many new writers who will write in detail the Crimea’s history of 2014–2017, describe this annexation, these trials, and this prosecution, and this is how this period will go down in the history of Russia.

The history of Russia in 2014 will be restored much earlier than the history was restored and the truth was said about the repressions of the 1930s, very soon. And years 2014–2017 will go down in history as they are.

And I do not understand why this huge nuclear country, which could become the richest and happiest country in the world but preferred the disgrace of prisons, prison camps and political trials, preferred poverty and trampling on the rights of her citizens, needed all this today.

What does today’s Russia need this for? What for, in the 21st century, when the whole world already lives by normal laws, when all the countries respect their citizens, and citizens respect their state? What does Russia, which flagrantly demonstrates disrespect for her citizens, while the citizens show contempt for their persecutor state, need this all for? Such a Russia is difficult to understand, this cannot be measured not only by “ordinary yardstick” but this is incomprehensible both for common sense and the law!

Therefore, it is obvious that Russia is standing today on the eve of major qualitative changes in politics. It will take a little time—I think up to 2–3 years—and the political situation in the country will radically change. All the political cases will be reviewed and their victims will be rehabilitated. How will the participants in these political trials for the prosecution’s side feel then?

I foresee that within the next 2-3 years, the world community will again decide on the status of Crimea, and then all possible options will be considered: the return of Crimea to Ukraine, the Crimean Tatar national republic, and the options of an independent state, and all the other options. But one thing is clear: that none of them will concur with its current status as unlawful, that the decision will be made on the basis of international law, and that all those guilty of violating the law in 2014–2017 will be punished.

In the first place, the right of citizens to express their opinions will be restored.

Today, unfortunately, as already mentioned, we have a paradoxical legal collision. On the one hand, there is part of the legislation drawn up in accordance with international law and respecting the rule of law. On the other hand, there are recently written new laws contradicting both the Constitution and previous laws, where the principle of the rule of law is not observed, which are not harmonized with international law, politically biased, and lead to politically motivated sentences.

Freedom of speech is the fundamental function of civil society, which ensures the right of citizens to information, and only then will they be conscious citizens, builders and reformers of their state when they have full and genuine knowledge of the processes in society, can judge all things freely and knowingly, without deception and mistakes.

Therefore, this verdict, if it proves to be damning, is a verdict not so much to me, a Ukrainian journalist, but rather to all journalism in Russia. For if there is no freedom of speech for all and no freedom of expression for all, there is no journalism as such, if there is no freedom of speech, there is no civil society, and if there is no fair justice, there will be no lawful society, and then citizens cease to be citizens and become vassals. Only one thing is necessary, that is, that everyone has the political will for that. And, to my mind, it will emerge soon.

On the other hand, a verdict in this case based on international law will give hope to all Russian journalists that not only their professional rights but the right of all citizens to know the truth and to freely obtain information about all events can be protected.

And now, Your Honor, against this whole political, economic, international, legal, and literary background, I am in your will. I have said everything as it is and how it should be in life.

/Mykola Semena, Crimean journalist, author at Radio Svoboda and Krym.Realii