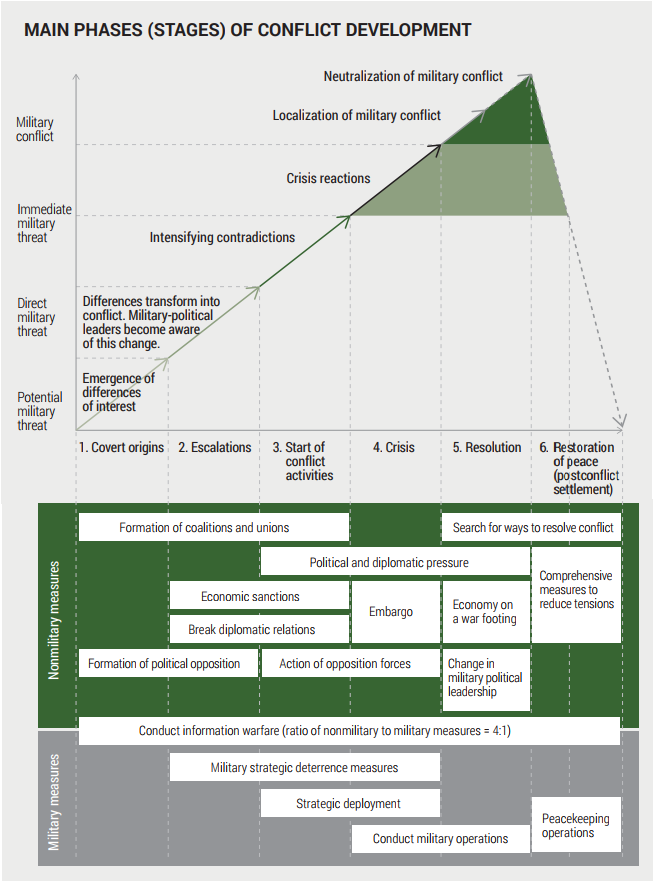

In February 2013, a year before Russia invaded the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea and unleashed war in eastern Ukraine, General Valery Gerasimov, Chief of the Russian General Staff, published a short piece on “the value of science in forecasting,” in which he outlined the contours of future warfare, predicting its such key features:

- it will be undeclared.

- it will see a broad use of kinetic and non-kinetic tools in close coordination.

- the distinction between the military and civilian domains will become still more blurred.

- battles will take place in the information space as well as in physical arenas.

Predictions such as these illustrate the so-called hybrid warfare. The term refers to the use of both kinetic, related to the motion of material bodies and the forces, and non-kinetic operations, seeking to influence a target audience through media, computer networks, electronic warfare etc. Alternatives to the hybrid warfare term include a return to “asymmetric warfare” and a move to the newer “ambiguous warfare.”

Modern information technology now serves as a force multiplier on an unprecedented scale and its effective use of the information space may compensate for deficiencies in the physical arena much more today than until very recently.

Russian hybrid war

Gerasimov’s 2013 article has since been condensed by many in the West into the “Gerasimov Doctrine.” There is no official doctrine and Gerasimov was, rather, depicting the world which Russia is confronting. “Hybrid warfare” in Russian parlance is described as a tool usually employed by the West, while the preferred Russian terms are “nonlinear warfare” or “new generation warfare.” However, many Western observers see Gerasimov’s 2013 article as a semi-official statement on Russia’s approach to warfare and as a blueprint for Russia’s 2014 occupation and subsequent annexation of Crimea as well as its involvement in the conflict and war in eastern Ukraine.

According to Russian military thinkers and analysts, [highlight]hybrid warfare basically encompasses any type of action designed intentionally to weaken an opponent[/highlight], even through, for instance, economic, cultural, or environmental policies. The essence is often described as “controlled chaos.”

Thus, Russian thinkers often depict a kind of “chaos button,” which may be used to adjust the level of chaos inflicted on a target state.

[highlight]The aim is to cause and feed instability, to weaken the social fabric of a society and to complicate and undermine decision-making[/highlight]. The target state should, ideally, be decisively weakened along the two overall dimensions of legitimacy which serve to define its position on a continuum of strong and weak states. Firstly horizontal legitimacy, defined here as the extent to which the population of a state accepts their inclusion in this. And secondly, vertical legitimacy, defined here as the extent to which the population of a state accepts the right to rule of those who rule.The “chaos button” may be used to adjust the intensity of both kinetic and non-kinetic operations. The former may cover the full spectrum of weapons available, but the focus is usually on small-scale and covert operations conducted by special operations forces or by irregular insurgents (in the Russian writing on the issue often referred to as ‘partisans’) or even terrorist groups supported by the enemy state(s).

The state waging a hybrid war is attempting to identify vulnerabilities in the target state(s), which may be used to further their own interests.

The Russian media landscape

Under Putin’s presidencies and his premiership, what is labeled a “neo-authoritarian” or “neo-Soviet” media system is being established in Russia. According to media watchdog Reporters Without Borders, with a score of 49.03, Russia in 2016 ranked 148 out of a total of 180 states surveyed. On a par with states such as Malaysia, Pakistan, Mexico, and Tajikistan.

The pressure on independent media has grown steadily since Vladimir Putin’s return to the Kremlin in 2012. Leading independent news outlets have either been brought under control or throttled out of existence. While TV channels continue to inundate viewers with propaganda, the climate has become very oppressive for those who question the new patriotic and neo-conservative discourse or just try to maintain quality journalism.

The government also has strong control of the media environment and has been able to retain domestic support despite an ongoing economic slump and strong international criticism.

Given the existence of this independent public sphere, how can the Russian media sphere be part of an authoritarian system? John Dunn has used the Italian term lottizzazione to describe what is essentially a two-tier system where the most important media outlets, that is, those in the larger tier one, are tightly controlled, whereas the less important ones are allowed a measured degree of freedom in the second smaller tier. We should see this as a politically controlled process, where members of the regime decide the fate of a vast number of media outlets by assigning them to either tier one or two and by subsequently promoting and relegating them according to their public impact: [highlight]all the influential outlets are found in tier one and have a pro-regime editorial line, whereas the less influential ones are in tier two and enjoy relative editorial freedom.[/highlight]

Tier one contains, most importantly, television which has become, as elsewhere, the main source of news, entertainment, and information for Russian media consumers. State-controlled television is considered one of the most trusted and authoritative institutions in the country and among these various television stations Channel One (Perviy Kanal), controlled by the Kremlin through a state majority ownership, has the largest share of viewers and thus possibly the largest impact.

The internet is still in tier two. However, while, as noted, in principle it remains accessible, the Russian authorities have taken measures to deny public access to an increasing number of addresses under the pretext of combating “extremism” as well as measures putting greater pressure on service providers such as social media site Vkontakte to shut down anti-regime fora.

This short description of the Russian media landscape is important for understanding how the Russian authorities may use the media to further a particular set of interests. In the influential tier one, in general, executive, legislative and judicial voices blend and are echoed by editorial and op-ed sources, expert commentators and voices from the street – all combine to create a well-controlled media space with a minimum of dissonance.

The basic tenet of the Russian disinformation strategy is the claim that all news is constructed and therefore contested. In the best postmodern tradition, there is no ‘objective news’ – only different, rivaling interpretations which purport to show different aspects of what may be called “reality.”

The weaponization of information

The term “the weaponization of information” is often used to describe this highly instrumental use of the media, including social media, to further particular interests. Slightly dramatic perhaps, within the present context the term alerts us to the fact that [highlight]the media is incorporated into Russian political thinking not as a constraint but as an asset to be used in the pursuit of various goals.[/highlight]

A current meta-narrative in Russia may be the claim that “the West is locked in centuries-old conflict with Russia.” It is reinforced by the heavy focus on military preparedness in Russia, ranging from the emphasis on patriotism to the very public celebration of the country’s nuclear arsenal. The claim is put forward at such an abstract level that it is mainly a matter of personal belief. Its dominant use by the Russian media should, therefore, be regarded as a case of extreme one-sidedness and untold stories, that is, strong media bias.

[highlight]The day has come where we recognize that the word, the camera, the photograph, the internet, and information in general have become yet another type of weapon, yet another expression of the Armed Forces.[/highlight] This weapon may be used positively as well as negatively. It is a weapon which has been part of events in our country in different years and in various ways, in defeats as well as in victories.The state-controlled Russian media serves as a force multiplier. It augments other capabilities, kinetic as well as non-kinetic, which the Russian state may employ in its pursuit of political goals. It is difficult to assess how great a force multiplier the media is, but there is no doubt that the greatest effect is felt within the domestic neo-authoritarian media space. Within this setting, it serves as a defensive tool mainly, as [highlight]it is designed to protect and preserve the existing political order.[/highlight] As alternative Russian voices are few and far between and, quite literally, on the periphery, and external voices find it hard to penetrate this media space, there is ample opportunity for the Russian regime to offer its meta-narratives and smaller narratives in a largely uncontested manner.

Western states and organizations should evaluate existing counter-measures and, if necessary, design and implement additional ones.

Cognitive resilience

As mentioned earlier, the Russian media strategy seeks to exploit the vulnerabilities of liberal democratic media. For the EU, for instance, the challenge is how to counteract information spread by internal or external actors, which is deliberately false or is characterized by omitted facts or one-sided analyses and is seeking to undermine support for the fundamental norms – or collective identity – of the Union.

In response to this challenge, the EU has established the East Stratcom Task Force, possibly the most widely recognized, and criticised, anti-disinformation unit set up to handle Russian disinformation. Several similar agencies, within state structures or organizations, exist.

All states may legitimately ban certain utterances, but it is futile to attempt to prevent disinformation from entering the information space.

The active debunking of disinformation, via a meticulous deconstruction of the news items, is advisable in extraordinary circumstances, such as the risk of heightened tension or even outbreak of conflict within a state or between states, as well as for educational purposes. It may alert the public to the fact that disinformation exists and help news consumers distinguish between different forms of information and better identify the false or biased stories. The challenge of disinformation should be viewed as a systemic challenge, however, and [highlight]the search for possible solutions should therefore focus on systemic responses.[/highlight]

The DIIS report suggests focusing on the build-up of greater cognitive resilience, that is, the ability to withstand pressure from various ideas spread, for instance, through disinformation. The term “resilience” is now widely accepted as a concept relating to the protection of critical functions of society and the “cognitive resilience” term is very similar, only it plays out in the cognitive domain as opposed to the physical domain. In essence, it will allow for the free flow of information, including from Russian state-controlled media, but it will establish a cognitive “firewall,” which prevents the disinformation from taking root and being internalized by members of the target audience. Unless extraordinary circumstances dictate a (temporary) ban directed against specific media outlet(s), and this may be fully legitimate, the flow of information should remain uninterrupted.

Ideally, the cognitive firewall should be installed at both the collective and at the individual level. At the society-wide level, the ability to recognize and subsequently reject disinformation and not give it the attention which it demands should be improved.

The contribution of the non-systemic responses should not be underestimated, but the main deficiencies of these relate to time and adaptability. Thus, [highlight]by the time a piece of disinformation has been debunked, the world of media has moved on, producing a vast number of new items in the process.[/highlight] And as sites are being flagged for disinformation content, new ones will emerge.

There will not be any easy or fix-it-all solutions to this development. Rather, liberal democracies, especially vulnerable as a result of their free media culture, should prepare themselves for a long-term commitment to countering disinformation and to building up cognitive resilience to ensure that the former has minimal effect. It is important to continuously evaluate and adjust, if only for the reason that the producers of disinformation will also do so.

Read the full report Russian Hybrid Warfare – A Study Of Disinformation by Flemming Splidsboel Hansen (pdf).

Read more:

- Russia using “organized chaos” to subvert Ukrainian government – analyst

- Disinformation across ages: Russia’s old but effective weapon of influence

- Kremlin disinformation campaign extremely successful – EU East Stratcom

- Internet bots are key players in propelling disinformation: study of 9 countries

- Baltic past and present successes explain Moscow’s schizophrenic propaganda response

- How Kremlin propaganda made the EU an enemy in the eyes of Russia

- Media in Russian-occupied Donbas increasingly like those of North Korea, study finds

- Moscow enjoying great success with far left parties in Europe

- Inside RT and Sputnik: What is it like to work for Kremlin’s propaganda media?

- 25 ways of combatting propaganda without doing counter-propaganda

- The propaganda schemes of TrumpPutinism

- Belarusian study highlights six aspects of Moscow’s new geopolitical strategy

- Russian propaganda exploits German feeling guilt for attacking USSR – Yuriy Durkot

- Human sacrifices for the Kremlin’s propaganda machine: meet the “Crimean saboteurs”

- European security experts call upon EU to triple defense against Russian propaganda

- Intimidation as a propaganda tool in the Nordic countries

- Email chains and other Russia’s propaganda tools in central and eastern Europe

- Putin’s anti-Ukrainian propaganda playing role state anti-Semitism did in Soviet times

- “Immortal regiment” march in Toronto – shameful display of Russian propaganda

- In the depths of disinformation: this is how RT propaganda works

- A Russian propaganda site incites breaking up Baltic countries