The 74-y.o. mother of the prisoner Natalya has sent a wrathful letter to Russian President Putin, where she expresses her indignation over the political repression that has befallen her family.

Natalya Balukh emphasizes that the only appropriate answer to her letter would be to correct the lawlessness committed against her son as she does not want to listen to the idle talk of Russian propaganda anymore.

“Every day,” she writes to Putin, “you declare from TV screens the greatness of the [Russian] state and the exceptional spirituality of the Russian people, you call on this people to protect “their own” state and defend it from someone.

You keep talking in my TV set and I’m not turning it off because I’m afraid of staying completely alone in a lorn house: I just mute it and feel for sure with each cell of my exhausted body, with all the fibers of my suffering soul: [...] this very state is seizing my son, whom I have not seen already for eight months and fear not to see him ever—as nobody would wish even to an enemy such a life when, on your 75th year, you are losing the dearest one, your hope and support, when the pivot, which connects you to this world, is pulled out from you with flesh and unbearable pain.”

Volodymyr Balukh is a farmer who lived with his family in north Crimea. Starting from December 2013, when the Euromaidan Revolution of Dignity was underway, he raised the Ukrainian flag on the roof of his private house. After the revolution was over in Kyiv and Russia occupied the Crimean peninsula, he installed a plaque with the inscription “Heroes of Heavenly Hundred Street” on his facade. The plaque was to commemorate dozens of activists killed in the center of the Ukrainian capital in February 2014.

This latter fact was enough to make him an outcast in the eyes of the local occupation authorities and collaborators among the residents of his village. Since the spring of 2015, masked officers of the state security with machine guns routinely invaded his house, searched it and tore down the flag from the roof.

Russian police detained Balukh four times under the pretext of “disobeying” their demands before a more sophisticated criminal case was fabricated against him.

“It is clear why law enforcers want to shut Balukh up in jail,” explained the lawyer Olga Dinze:

“He has an active stand regarding Crimea and its incorporation into Russia. He considers himself a citizen of Ukraine, whom he essentially is, and is not going to accept Russian citizenship in any way. He is against this and clearly shows [his position], demonstrating a Ukrainian flag on his houses [that is, his own house and his wife’s one]. Of course, the officers of Crimean state security dislike him. And so they simply decided to take him away.”

Volodymyr tells that he was openly offered a choice: to leave Crimea or to go to prison. He was ready to move to mainland Ukraine with his family but his mother refused to escape from the land where her ancestors were buried.

At the end of 2016, Russian law enforcers again arrived to search his wife’s house. One of them climbed up to the loft (right beyond the roof, where the flag had been waved) and “found” there a package with five TNT blocks, seventy cartridges, and nineteen shells. According to the allegations of the occupation police, the materials appeared in the house because Volodymyr had “often gone to [mainland] Ukraine.”

The cartridges, as noted in the criminal case file, were produced in Barnaul (Russia’s West Siberia) back in 1982. The court turned down the prisoner’s request for the use of polygraph during the questioning.

After the arrest, Balukh was openly blamed for not renouncing Ukrainian citizenship and refusing to admit the Russian one.

In his last word before the court, Balukh admitted that he could have avoided the real prison sentence if he had broken down and acknowledged his “guilt.” However, he said, that was not an option for him:

“I don’t want my descendants, the children of all of Ukraine, to reproach me for acting cowardly or being weak.”

This is not the only case when the Russian law enforcement had persecuted people for publicly displaying Ukrainian symbolics. For instance, in August 2014, a school teacher was detained in St. Petersburg for a “provocation”: he had a blue-and-yellow cap with the word “Ukraine” on his head during the celebration of the Russian Flag Day. In March 2016, Russian security officers beat the Moscow University postgraduate Zakhar Sarapulov after he hang the Ukrainian flag out of the window of his room in the dormitory on the third anniversary of the annexation of Crimea. Later Zakhar was expelled from the University.

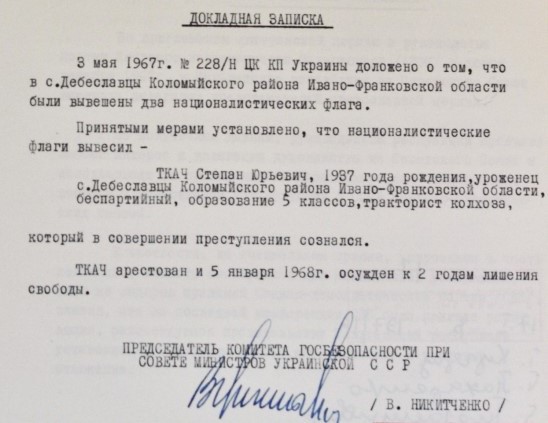

With these and more similar acts, Russian authorities reproduce the ugly practices of the Soviet KGB, which for decades hunted for the “criminals” who installed blue-and-yellow flags all over Ukraine. For instance, fifty years ago, in 1967, the KGB arrested a village tractor driver Stepan Tkach, who “confessed” to raising two “nationalist” flags in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, West Ukraine. Tkach was later sentenced to two-year imprisonment.

The 2017 sentence in the Balukh case, which is almost two times longer, is unprecedented even against the background of the general atmosphere of paranoid Ukrainophobia in today’s Russia.

The authoritative watchdogs, Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, Crimean Human Rights Group, and Human Rights Information Center recognized Volodymyr Balukh as a prisoner of conscience. They also called on the EU and governments of democratic countries to introduce personal sanctions against the 23 judges and officers of the Russian Federal Security Service, Investigative Committee and occupation police linked to the political persecution of Balukh. The Ukrainian Helsinki Union, in addition, lodged two complaints regarding his unlawful conviction to the European Court of Human Rights.