Read the previous parts:

In the West, much sympathy existed with Hitler on the basis that the treaty of Versailles had treated Germany too harshly and the belief that Hitler was simply getting back what many thought rightly belonged to Germany.

On September 26th, 1938, Hitler proclaimed that the Sudetenland was his “last territorial demand in Europe.” But given that this demand threatened to ignite a war that neither the British or French wanted, Brtish Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain most infamously acquiesced to it calling the settlement of the Munich agreement “peace for our time.” The Czechoslovak government left without support from the West was browbeaten into accepting Munich even though it left the rest of the country vulnerable.

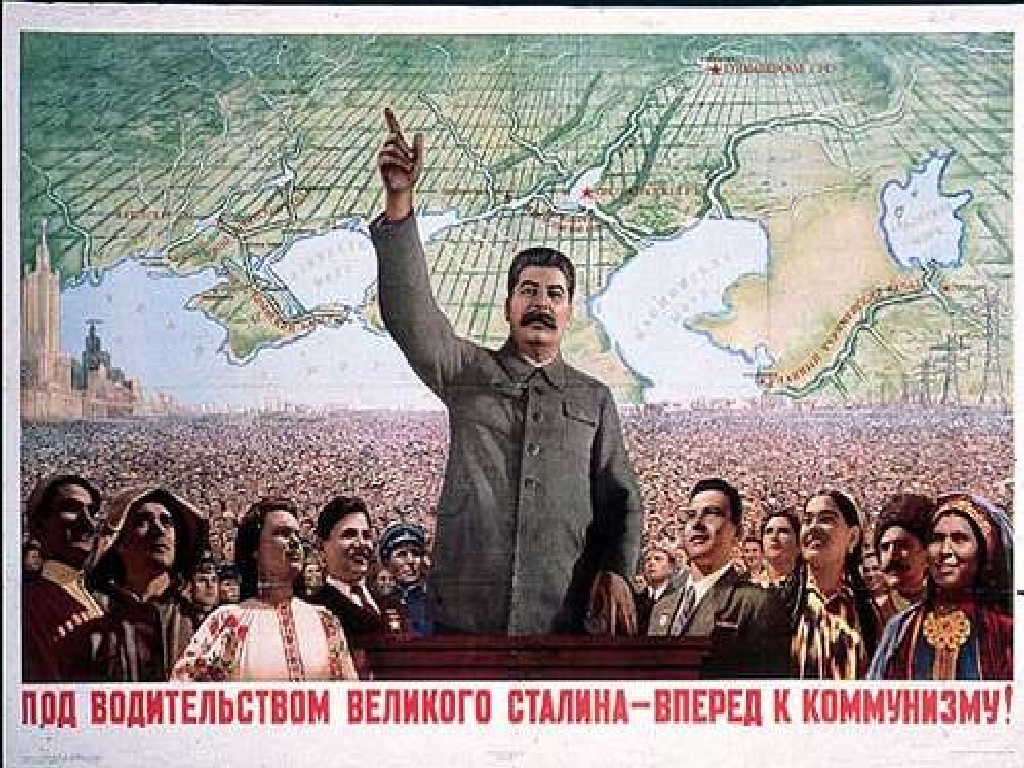

Stalin's "poker worldview"

The Soviet Union wasn’t invited to the discussions and this has prompted much commentary. According to the interpretation by a contemporary Russian propaganda agency, this “proved” that the West was in the process of creating a conspiratorial proto-NATO bloc in order to threaten the USSR.

To Stalin, this was evidence that the West wasn’t serious about either Hitler or him. On March 10th, 1939, Stalin gave a speech claiming that the world was being divided into the spheres of influence of aggressor and non-aggressor states alike. Britain and France, he claimed, were making concession after concession to the aggressors (here an oblique reference to Hitler) because they were eager for a war between the “aggressors” and the Soviet Union so that they would “weaken and exhaust one another” to the point where the USSR would be forced to accept the dictates of capitalism. [1]

This rhetoric was but a mirror image of his own. On January 19th, 1925, for example, Stalin gave a speech claiming that the pre-conditions for a new war analogous to World War I were being sown by the divisions of the capitalist powers and that “if war breaks out we shall not be able to sit with folded arms. We shall have to take action, but we shall be the last to do so. And we shall do so in order to throw the decisive weight in the scales, the weight that can turn the scales” towards the establishment of Soviet rule all throughout Europe. [2]

Simon Sebag-Montefiore in his biography of Stalin summarized that the Soviet dictator viewed diplomacy as a “game of poker,” in which each player (the USSR, Nazi Germany, France along with Britain) was aiming to let the other two destroy each other in order to collect the winnings. It that speech on March 10th, Stalin warned the West that he would not be pulling the “chestnuts out of the fire” for anyone.

Again it was a sign that Stalin was willing to work with those who would further his interests best. On May 3rd, 1939, Stalin announced that he had fired his foreign secretary Maxim Litvinov, who, it was publicly noted, was of Jewish origin, and replaced him with the more stout ideologue Vyacheslav Molotov.

If you follow contemporary Soviet apologists, you might find yourself stumbling upon a 2008 article from the British newspaper Daily Telegraph reporting that on August 15th, 1939, Stalin proposed an anti-German alliance to the British and French 8 days prior to the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, even after Czechoslovakia had been dissolved!

The key demand Stalin made to the British and French was that the Red Army ought to cross Polish territory. How convenient a detail is because, as we know in retrospect, once the Kremlin orders its army into another's territory, it attempts to stay there for eternity. The claim that Stalin turned to destroying Poland with the Germans because he couldn't destroy Poland—the very country that he was for so long obsessed with conquering—with French and British assistance more than ought to raise eyebrows.

As the Telegraph article points out, the British and French at the time didn't meaningfully respond to the Soviet demands. The British representative Sir Reginald Aylmer Ranfurly Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax had actually arrived in Moscow by slow steamship and without the authority to conduct diplomacy causing Stalin to comment: “They’re not being serious. These people can’t have the proper authority. London and Paris are playing poker again…” [3]

At any rate, neither the British nor the French had any appetite for fulfilling Stalin’s demand for Poland. On March 14th, 1939, Hitler moved to annex the remainder of Czechoslovakia creating the “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.” It gave away his propaganda lie that his expansions were only to “protect” Germans and to an extent jolted Britain and France into supporting Polish independence with a guarantee on March 31st.

On April 6th, both London and Warsaw pledged to formalize the guarantee as a military alliance which would eventually be concluded with a pact signed on August 25th. It was something that other than a declaration of war on Germany on September 3rd, 1939, the British and French absolutely failed to fulfill.

Even today, there are numerous apologists of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, from Putin’s nationalist-dictated Russia to pro-Russian parties abroad that try to draw a moral equivalence between the Nazi-Soviet alliance and Chamberlain’s policy of appeasing Hitler over Czechoslovakia. Yet this is wrong. After Munich, the British government gave the Czechoslovak government loans and donations and also set up a "Czechoslovak Refugee Trust" to deal with those who had fled to Czechoslovakia to escape persecution from German-occupied Sudetenland and from Nazi Germany.

Obviously, these actions were too little and too late to alleviate the consequences of appeasing Hitler but they do illustrate a fundamental difference in attitude between the British with regards to Czechoslovakia and the USSR with its alliance with Nazi Germany. After all, when Hitler moved his army into the rest of Czechoslovakia, they were not met by the British Army to hold a joint victory parade in some symbolic city. Both the USSR and Nazi Germany had war and territorial conquest in mind in September 1939. Britain's effort in the Sudetenland crisis was a fundamentally foolish effort to preserve peace with a dictator that it thought could be reasoned with.

Nazi propaganda claimed that the annexation of the Sudetenland represented a popular triumph of the Fuhrer and his will, though in private Hitler did complain that Chamberlain had cheated him out of a war. Regardless, the annexation of the Sudetenland only fuelled Hitler’s lust for expansion. In a speech to a selected group of journalists on November 10th, 1938, Hitler talked about the way he presented himself:

“Circumstances have forced me to talk almost exclusively of peace for decades. Only by constantly stressing Germany’s desire for peace and peaceful intentions was it possible for me to win the German people their freedom bit by bit and to give the nation the arms which were always necessary as the prerequisite to the next step. It is obvious that such peace propaganda, carried on for decades, also has its dubious aspects; for it can easily lead to fixing in the brains of many persons the notion that the present regime is identical with the decision and the desire to preserve peace in all circumstances.

That, however, would lead to a false idea of the aims of this system. Above all, it would also lead to the German nation’s… being imbued with a spirit which in the long run would amount to defeatism and would necessarily undo the achievements of the present regime. The reason I spoke only of peace for so many years was because I had to. It has now become necessary to psychologically change the German people’s course in a gradual way and slowly make it realize that there are things that must, if they cannot be carried through by peaceful means, be carried through by the methods of force and violence…. This work has required months, it was begun systematically; it is being continued and reinforced.” [4]

Poland between the hammer and the anvil

Polish foreign policy has also come in for some spotlight. One might think that the Carpathian mountains have always provided a natural border for the Poles to the north and Czechs/Slovaks to the south but the mountain passes such as at Cieszyn/Těšín were ethnically mixed. This gave way to competing territorial claims.

On January 23rd, 1919, Czechoslovakia invaded and fought a short war with Poland over the mountain passes which Poland duly lost. It is certainly true that Warsaw’s relations with Prague were marked by a sense of revanchism which motivated the Polish seizure of the passes on October 1st, 1938, against a weakened Czechoslovak state. Of note, we have the diaries of Jan Szembek, Polish undersecretary for foreign affairs at the time, and Józef Beck, longtime Foreign Minister under Józef Piłsudski. Reading both, one gets the idea that the way they justified the annexation of “Cieszyn-Silesia” was to actually save the area from German occupation.

Szembek goes on to mention that Beck had long-term ideas for an anti-German dam from Poland to the Balkans on the back of a disintegrated Czechoslovakia. Perhaps this may not be an emotionally convincing explanation given that the creation of this anti-German dam necessitated scenarios that didn’t come to pass. But Soviet apologists have a tendency to go further and conjoin this to Józef Piłsudski’s signing of a non-aggression pact with Hitler in 1934.

In 2009, a self-styled documentary titled Secrets of the Secret Protocols was aired on Russian TV alleging that the 1934 pact contained secret protocols aimed against the USSR, which would carve up the whole of the rest of Europe with Hitler. Among its most notable contributors was Alexander Dyukov, a Russian nationalist historian known after his denials of the scale of Soviet mass deportations undertaken under Stalin. But even he could only bring himself to claim that the existence of these protocols was only an assumption without evidence. It should be telling that the Polish-German pact of 1934 was a different type of treaty to the one the USSR made with Hitler in 1939. In fact, it is more akin to the aforementioned Polish-Soviet pact of 1932.

What is less known about Polish diplomacy during this era is the arguably circumstantial evidence that, before the signing of the Polish-German pact, Piłsudski proposed to the French the idea of a preventative war against the Germans, which the French rebuffed, causing Piłsudski to sign the agreement with Germany.

“As the Marshal [Piłsudski] said to me, he had thoroughly examined the pros and cons, and all the chances of a preventative war, before taking the decision to negotiate with Germany... In the military sphere, the Marshal calculated that the weakest point of our armed forces was the higher command. The weakness of our eventual allies in that period made us abandon the idea of a preventative war.”

Regardless of the public platitudes that the two pacts with Germany and the USSR generated, it is clear that privately Piłsudski and his successor Edward Rydz-Śmigły saw both Nazi Germany and the USSR as threats to the Polish state. As a result, two distinct military plans were drawn up to deal with either threat: Plan Zachód to deal with Nazi Germany and Plan Wschód to deal with the USSR.

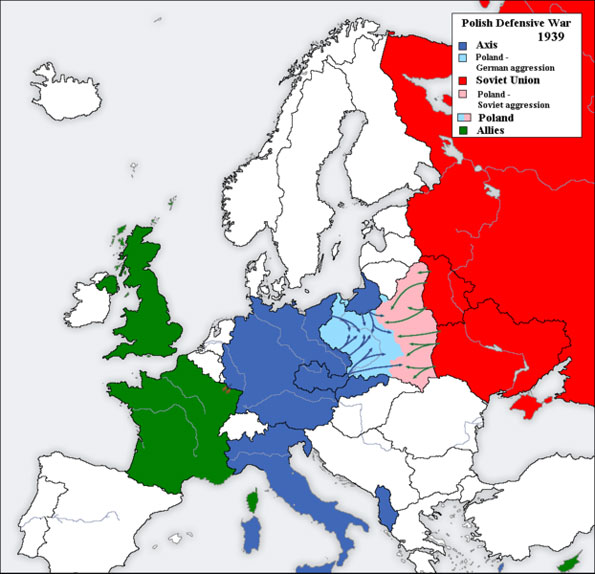

Neither plan though anticipated both threats being allies. Plan Zachód, the plan enacted in September 1939 revolved around keeping hold of South-East Poland (Western Ukraine) so that Western supplies and aid could be drawn from the Romanian port of Constanta. The Poles relied on promises from both France and Britain that they would receive aid in the event of a German onslaught. In reality, no such aid ever came and the Soviet invasion made Plan Zachód redundant.

Pillars of Nazi-Soviet "friendship"

Regardless of the “wrongs” of Polish or Western foreign policy before 1939, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact represents a completely different category of malevolence.

On August 19th, 1939, Stalin was reported to have given a speech in which he stated that "our aim is to ensure Germany can continue to fight for as long as possible, in order to exhaust and ruin England and France. They must not be in a condition to rout Germany. Our position is thus clear… remaining neutral, we aid Germany economically, with raw materials and foodstuffs. It is important for us that the war continues as long as possible, in order that both sides exhaust their forces."

Whilst this seems to chime with what we know of Stalin’s motives and Soviet ideology, the very existence of these words has been put into question by Russian historians. Whether or not they are Stalin’s words or a caricature of Stalin still remains up for debate. What we do know is that on July 1st, 1940, Stalin told the then British ambassador to the USSR Stafford Cripps:

“During the pre-war negotiations with England and France, the USSR had wanted to change the old equilibrium... England and France had wanted to preserve it. Germany had also wanted to make a change in the equilibrium, and this common desire to get rid of the old equilibrium had created the basis for the rapprochement with Germany.” [5]

Molotov in his later years commented in the context of early Cold War diplomacy: “My task as minister of foreign affairs was to expand the borders of the fatherland as much as possible. And it seems that Stalin and I coped with this task quite well.” The Soviet alliance with Nazi Germany must also be seen in that way. Stalin’s lust for land and getting Hitler to turn west have to be factored as the major reasons for him agreeing to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact.

Read also: Seven decades ago, the Soviet Union entered the war as the chief “accomplice of Hitlerism”

Why Hitler agreed to such an alliance with Stalin is usually seen as much more straightforward. Though Von Ribbentrop claimed it “as his very own idea” that he convinced Hitler to pursue, he admitted: “because I sought to create a counter-weight to the West and because I wanted to ensure Russian neutrality in the event of a German-Polish conflict.” [6]

Regardless of whether Von Ribbentrop knew it or not, this line played straight into the hands with Stalin.

Hybrid war, 1939

In the run-up to the outbreak of war with Poland, Hitler employed the same tactics as he did prior to the Sudetenland crisis, trying to convince his own people and the West that he was a man of peace and that Danzig, in particular, would be his last demand. Curiously, the Germans also employed a prototype version of what we now call “hybrid warfare.” On August 4th, 1939, the “Danzig customs crisis” erupted after a German Militia had been formed and supported by Albert Forster who in turn had taken his cues from Berlin to foment German-Polish agitation. By late July, this Militia had been bolstered by SS troops, who had entered the city in the guise that they were all going to a sporting contest.

Their intent was to disrupt with physical force the Polish customs officials monitoring imports so that German arms could flow freely into the hands of any sympathetic German residents of Danzig. All the meanwhile, the German army began mobilizing on the border. On August 4th, this came to a head when Warsaw called Hitler’s bluff by threatening to enact a shutdown of the port completely to all German supplies, including food imports. In Nazi propaganda, this was claimed as an example of “Polish terror” against the Germans of Danzig.

Read also:

- Plagiarism scandal in Russia: Hitler’s speech copied for Crimea annexation

- Hitler’s anschluss and Putin’s: Similarities and differences

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HLNa7XCmnDg?ecver=1]

Throughout 1939 and particularly in the lead up to the outbreak of WWII, Nazi propaganda openly intensified against the Poles, culminating in what is commonly dubbed “Operation Canned Meat” or “Operation Himmler.”

Simultaneously, Hitler’s regime fomented ethnic tensions between Germans and Lithuanians over Klaipėda (Memel) Region as a prelude to an ultimatum issued on March 20th, 1939, to the Lithuanian government. The ultimatum demanded to give up the region to Prussia and to ensure that Germans in the remainder of Lithuania be given full protection in exchange for a Lithuanian Free Zone. By March 22nd, Lithuania had capitulated to these demands finding that the United Kingdom and France (signatories to a 1924 agreement stating that Klaipėda was Lithuanian) were still in appeasement mode and that the Germans were threatening invasion if they didn’t get their way.

Klaipėda was Hitler’s last territorial gain prior to September 1939 that involved not firing a shot. When the Soviets issued their ultimatum to the remainder of Lithuania in June 1940, the Germans helped put pressure upon the Lithuanians to accede to Soviet demands.

So the propaganda that both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union employed to justify their imperial conquests during 1939—41 bears considerable similarity to one another. When Stalin turned to conquering the Baltic states and Finland, Stalin fomented ethnic Russians and Communist agitators to cry that they needed “saving” from each government. The Mainila false-flag operation that Stalin used to ignite the Winter War against Finland in late 1939—early 1940 is highly comparable to the Gleiwitz false-flag operation that Hitler used to ignite the German invasion of Poland in September 1939.

As to the claim that the Soviet expansions were simply for defense, that raises more questions than answers. It certainly does not explain the depth to which Stalin’s regime collaborated with Hitler’s Germany between 1939—41, which has been expounded upon elsewhere. It doesn’t explain why old fortifications like the Stalin line were deliberately weakened. It also doesn’t explain why the Red Army performed so badly in the autumn of 1941.

Read also: Hitler-Stalin pact still casts a shadow over Europe 77 years on

As it turned out, the Soviet doctrine that the Red Army be ready to export "world revolution" put men and munitions into offensive rather than defensive posturing, which, in turn, played straight into the hands of the Wehrmacht. In the final analysis, the sheer depth of the collaboration between Nazi Germany and the USSR directly fuelled the same German aggression that the USSR would eventually be succumbed to in 1941.

Read also: June 22, 1941 – the day Hitler and Stalin ceased to be allies

Censoring history Putin-style

Much of contemporary Russian historiography is based around the concept that the USSR had always been engaged in a heroic and virtuous struggle against fascism, loosely defined. Putin has long made moves to make it illegal to criticize the Red Army, even on a tactical level. If you even point out that handfuls of Red Army soldiers looted and raped as they advanced against the Wehrmacht, particularly in the later stages of the war, you will be accused of promoting Nazi propaganda, as military historian Antony Beevor found out.

Read also: Fascism exploited and distorted in Putin’s Russia for propaganda’s sake

All the meanwhile, the Russian dictator has attempted to justify the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact on the basis of the propaganda lines outlined above to the point he claims that the USSR never invaded Poland in 1939. Criticize these lines and you will be accused of "dissemination of deliberately false information on the activities of the Soviet Union during the Second World War," which in Russia is a criminal offense, as Perm-based Russian blogger Vladimir Luzgin found out to the cost of 200,000 rubles when he wrote a post pointing out Nazi-Soviet collaboration.

Read also: Putin needs both: a Great Victory and a Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Even though this article deals mainly with the rationale behind why the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact came into being rather than its consequences, the fact that this article challenges Putin’s propaganda lines means that reading and sharing this post or translating it into Russian is now illegal in Russia.

For those who want to learn more about the consequences of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, the best contemporary introduction in English is The Devils' Alliance: Hitler's Pact with Stalin, 1939—1941 by Roger Moorhouse. As I type, it awaits both Russian and Ukrainian translations.

[1] The Collected Works of Joseph Stalin, Vol. 14, p. 366.

[2] Ibid., Vol. 7, p. 14.

[3] Quoted in Montefiore, Stalin, p. 273.

[4] Quoted in Joachim Fest, Hitler, p. 536—7.

[5] Quoted here

[6] Quoted here