I grew up in the West, where few people know much about Ukraine. In the USA—my home country—most people grow up thinking Ukraine is a part of Russia. They call it “The Ukraine.” If they have grandparents from Kyiv or Odesa, they say “my grandparents emigrated from Russia,” or describe their ethnicity as “Russian.” Ukraine is a footnote in Western history books—a part of various empires, history without a nation.

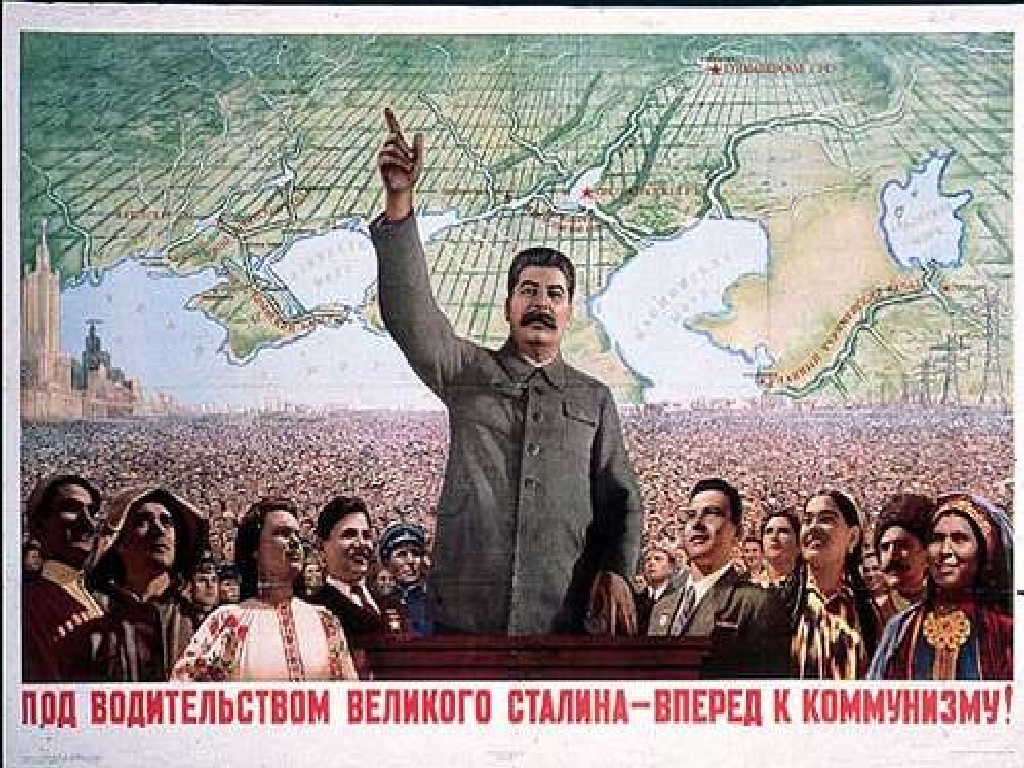

Maybe this is why most Westerners, when they come to Ukraine, fail to understand the culture. They don’t see Ukraine’s cultural evolution in its proper context, because the historical lens is skewed. What happens instead is one (or both) of two things. First, Westerners tend to echo Soviet-era propaganda—Ukraine has always been part of Russia, it’s within Russia’s sphere of influence, Ukrainian is an invented language, Ukraine is a fake country. Second, Westerners tend to make claims about Ukrainians and Eastern Europeans that would in any other context be described as racist. The two places where this is most conspicuous is when it comes to Western discussions of corruption, and of how Ukraine values human life and treats its civilians.

Maybe this is why most Westerners, when they come to Ukraine, feel entitled to lecture Ukrainians about how to be good global citizens.

Ukrainians understand their own history fairly well—certainly no worse than any other country’s citizens, and better than many (including citizens of the USA who routinely begin their country’s history in the early 17th

century with the arrival of the Pilgrims). There aren’t serious consequences for Westerners (British, Americans, Germans, Italians, French, and etc.) being ignorant about the various struggles and ordeals of Ukrainians over the centuries—it’s all part of the same broad, dismissive hand-wave Westerners normally assign to the Middle East, Africa, and countries from Ukraine all the way up to Finland. “What’s their history?” “Ah—I dunno. Russia. That whole Russia thing.”

Ukrainians are accustomed to this ignorance, and are eager to share the many important ways their country’s history diverges from Russia’s. Ukrainians appreciate that old feeling of kinship with the other Europeans they resemble, physically and culturally—it reminds them that Russia is a very recent part of Ukraine’s history, and reassures them that the antipathy with which they view that association is well-founded. They are so eager to please Western Europeans, in fact, that they lose sight of an important if not overwhelming historical fact—that Europe abandoned them in the 20th century. Once if you look at the outcome of World War One and the British, French, and American failure to protect Ukraine and Kyiv from the Soviet Red Army. Twice if you consider how World War Two played out. Three times if you count the Budapest Memorandum—and you should. You should definitely count that.

They’re so used to being called “little brother

” by Russians, and dismissed as antisemites (by Jewish refugees who only remember what the Ukrainians they encountered did in the concentration camps) or fascists (by Europeans who remember only what some Ukrainians did in WWII) that they’ve developed an inferiority complex of epic proportions. Their inferiority is so powerful, runs so deep, that it never even occurs to most Ukrainians that they actually have the upper hand—that, like Israel, they can hold history over the heads of the safe, comfortable Europeans and Americans who are so eager to criticize Ukraine.

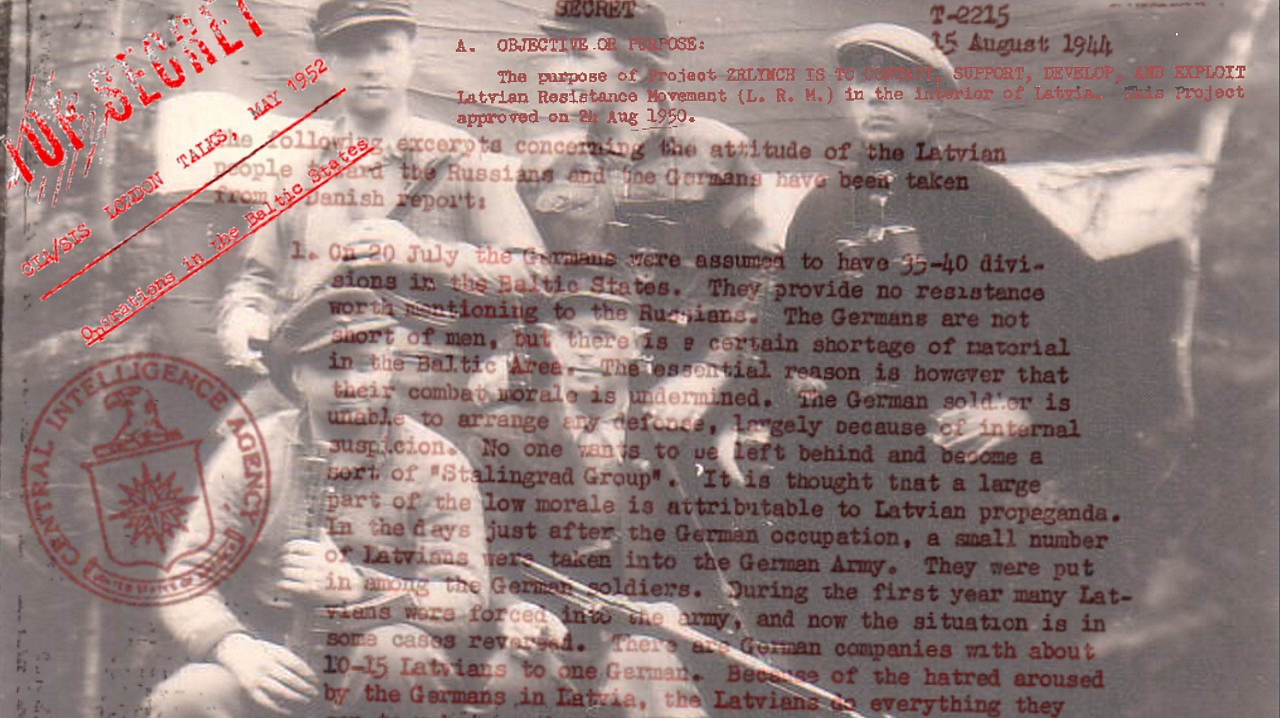

It’s time that Ukrainians recognize and embrace the fact that were it not for their suffering, the burden they bore for eighty years, it’s likely that the Red Army would have washed over Austria and Germany in 1919. Had it not been for their frequent and fervent rebellions from 1944-1954—the war they fought with Poland and with Russia, in which tens of thousands died, and hundreds of thousands deported—that Central Europe would have groaned under the yoke of totalitarian tyranny much earlier (in the case of Hungary and Czechoslovakia) and Western Europe might not have survived.

So the next time an American or Western European decides to lecture a Ukrainian about the choices Ukraine makes in its present moment or about its complicated history, instead of attempting to justify or defend it, Ukrainians should simply say “well, if you hadn’t abandoned us three times in the 20th century, maybe we wouldn’t have these problems. Oh, and by the way—what exactly have you done for us lately? Nothing? Yeah, thanks for that. Sorry—continue with what you were saying before.”

Adrian Bonenberger is a writer and Army veteran living in Ukraine. His accomplishments include publication in the New York Times

Adrian Bonenberger is a writer and Army veteran living in Ukraine. His accomplishments include publication in the New York Times

, Washington Post, Foreign Policy, and not believing obvious Russian propaganda.

Related:

- Orientalism reanimated: colonial thinking in Western analysts' comments on Ukraine

- Why do many Westerners show sympathy to Russia and Communism -- but not to their victims?

- How Russia's worst propaganda myths about Ukraine seep into media language

- Holodomor: Stalin's genocidal famine of 1932-1933 | Infographic

- History, Identity and Holodomor denial: Russia's continued assault on Ukraine

- The Ukrainian who saved Krakow from destruction and other little-known WWII heroes

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 1

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 2. Stories of Ukrainians in the Red Army

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 3. Of German plans and German collaborators

- Moscow's propaganda about Ukrainian anti-Semitism -- response to Ukrainian resistance, Ackerman says

- Ukrainians call upon Poles to establish mutual Day of Remembrance for Volyn tragedy victims

- Moscow historian Andrey Zubov: Banderites are an example of the great lie of the Soviet system