Ihor Popovych is a 83-year-old resident of Lviv who lived through the horrors of the Soviet totalitarian system - eviction from the family apartment, transit prisons, Gulag, and years of hard labour in the Far East. What scenarios were imagined by the infamous NKVD to liquidate members of Lviv’s elite? How did the Soviet system attempt to destroy Galician families?

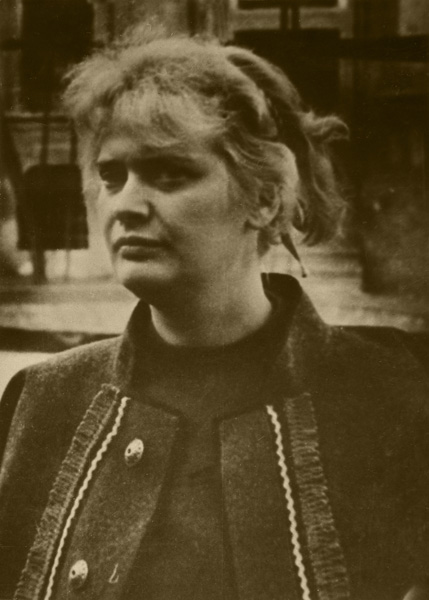

“I’m exhausted…” says Ihor Popovich as he opens the door to his apartment. He writes poetry, has an incredible memory, his eyes fill with tears when he tells us about his grandmother Teofilia, wife of Lev Yurchynsky, a Greek Catholic priest from Zbarazh (Ternopil Oblast). His grandmother’s strong will and patience helped him survive psychologically and physically during the long years of the family's exile in the Far East. He shows me boxes and photo albums that he reveres like relics. When NKVD officers came to evict the family from the apartment in 1949, these family mementoes followed them into exile.

Ivan was born in Warsaw, where his father Stepan, a former Ukrainian Sich Rifleman, worked as an engineer. The family returned to Ukraine during the Second World War, settling first in Ternopil region, where the grandmother Teofilia and grandfather Lev Yurchynsky, a priest, lived. When Ihor's grandfather died, the family moved to Lviv.

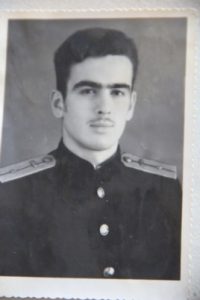

“I attended School No.44 in Lviv. But then it was time to join the Komsomol. That was in 1949. I was advised to change schools. Again, I got everything wrong… my marks were too high (I always got top 5s), but if I’d gone with 3s, I could’ve avoided the Komsomol. In short, I was given a high recommendation and sent to the district Komsomol committee. Everything went quite well until they asked me whether I believed in God. I went home and knew there’d be trouble. It was December. A few days before Christmas, at two in the morning, I heard cars screeching to a halt on our quiet street. Heavy steps on the stairs, the doorbell rang and there, on the threshold, stood three officers and six soldiers. We were given two hours to pack. Mom told us not to cry; we were being taken away. They searched our home, planted some documents about the history of Ukraine in our encyclopedia – it would make for faster and easier accusations. We packed what we could, took our pictures, and got in the car with my younger brother Borys, my grandmother, and Mom and Dad. Then, the colonel ordered my mother to go with him for an hour or two, and these two hours turned into long years of imprisonment and hard labour.”

The Popovych family was taken to the prison in Bibrka, and then moved to a Lviv transit prison, where the NKVD interned families from all over Western Ukraine.

“There were very, very many people. A small room with rows of three-tier bunk beds, more than 30-40 people per room, elderly persons and many children. A close-stool stood at the door; the food was awful… I was 16 years old. We were allowed to go outside for half an hour.”

The family did not know what had happened to Natalia Popovych, Ihor’s mother. The NKVD accused her of taking part in the Ukrainian underground movement. Natalia’s sister, Iryna, was in the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army-Ed.), so the whole family fell under Article 54/1, and was charged with “treason”.

Ihor’s mother later told him how the NKVD officers had staged a whole scenario to get her to confess… Their car supposedly broke down as they were taking her away. When the Soviet officer went to the village to look for a mechanic, the car was approached by some alleged “UPA” soldiers. They took Natalia to a kryyivka (underground bunker-Ed.), and interrogated her for three days about her alleged involvement in the underground movement. They obviously wanted information on her work with the UPA and the partisans.

“My mother knew this was all a sham, so she read poetry to them because she was a marvellous speaker. And then, the NKVD moved on to the second act - the soldiers threw a grenade into the kryyivka, dragged my mother out, and took her to the Prison on Lontskoho in Lviv. That was the end for her; there was no need for them to invent another reason for her imprisonment.”

Natalia Popovych was imprisoned for ten years. Her family - her 75-year-old mother, two sons and husband - were deported to Khabarovsk in the Far East.

“We were packed into animal transport wagons. There were three-tier bunk beds in each wagon. The youngest children slept on the top beds. I kept my cap on when I slept, but both my cap and hair froze to the metal pipes running along the roof. It was bitterly cold; we travelled for a whole month. There was one close-stool for all of us. The women were allowed to go and get food for the whole wagon. We’d stop at a train station, the soldiers would open the door and escort one woman to the kitchen where some slop was poured into a bucket. There were times when we had nothing to eat, so the train just moved on to the next station. There were many nice people in our wagon. I remember a family from the village of Mokrotyn; they had many orchards back home and were allowed to leave with a bag of dried fruit. When we had some charcoal, the man would stew the fruit and offer it to everyone in the wagon. We had some potatoes; nothing else was allowed.”

Ihor says they were lucky because they landed up in Khabarovsk Krai in the Komsomolsk Forestry Administration, where they were forced to cut trees and build roads. They were happy because Japanese military prisoners had left solidly built barracks and lots of wood they could use for heating. Each barrack housed several families; each family had a small separate corner with several plank beds. Ihor’s grandmother always had a cheerful word for everyone, radiating warmth, love and comfort.

“Grandma cooked for us while we were at work. Everyone loved her. She always wore long dresses. One day, a piece of charcoal fell on her dress and burnt her body. The forestry director was a good man, and he sent eight workers to help take grandmother to the hospital. The lake was shallow, and they pulled the boat with my grandmother lying in it for 18 kilometres. But, it was too late…she died in hospital. Only my father was allowed to attend the funeral. Grandmother is still buried somewhere on a mountain in Amurstal.”

Natalia Popovych learned about her mother’s death much later. She was released in 1956, travelled to the Gulag to see her family, and stayed with them until they were rehabilitated in 1961.

The family returned to Ukraine with no money or belongings. They had nowhere to stay, and for many years lived with relatives and friends. Ihor never went back to the house he had been forced to leave. He says it’s all in the past now…

Ihor Popovych graduated and worked in the construction industry in Lviv. He still writes poetry. His mother was completely blind when she died at 97.

In 2001, when His Holiness John Paul II visited Ukraine, Natalia Popovych wanted to give him an embroidered icon and a rosary that she had made with tiny pieces of bread during her internment in the Prison on Lontskoho. She had managed to preserve these objects during her detention, the Gulag period and resettlement. However, the Pope refused to accept them, saying that such important relics should be kept in Ukraine, and not in Rome. These objects are currently displayed in the Prison on Lontskoho Museum.

The war, repression, prison and exile were difficult for everyone. No matter how hard the Soviet totalitarian regime tried to destroy our people’s will, no matter how devious and destructive their mechanisms were, it was not able deprive them of their dignity and honour.