Brexit presents several new challenges for Ukraine.

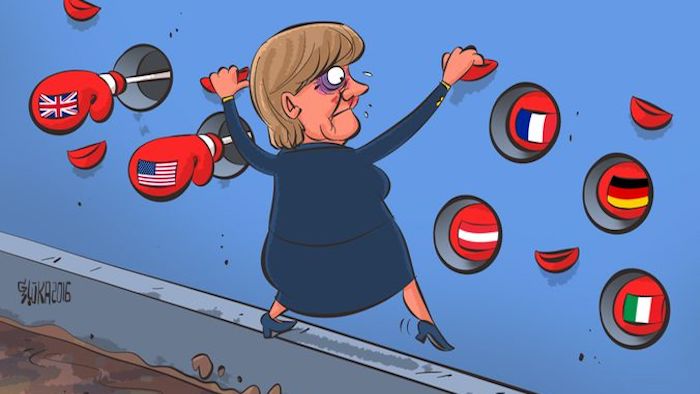

The balance of power within the European Union will change.

What should Ukraine do?

And, unfortunately, Ukraine receives these challenges before it is prepared for them.

Yevhen Hlibovytkyi is a Ukrainian expert of long-term strategies. He studies value systems and is a participant of the Nestor expert group, an informal gathering of intellectuals, experts, and civic activists working on developing a strategic vision for Ukraine.