May is a month for commemorations. Today, May 18, is the 71st anniversary of the deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar people from the Crimea Peninsula during World War II. This mass deportation, ordered by Soviet leader Josef Stalin who claimed to be rooting out Nazi collaborators, displaced 200,000 people and cost many thousands of lives as women and children were herded in cattle cars under inhumane conditions while the men fought in the Soviet Red Army.

Crimean Tatars have commemorated this ignoble act yearly by meeting in Lenin Square in the Crimea's capital, Simferopol, lighting candles and other rituals to remember and honor the victims who were unjustly exiled from their homeland. Last year, however, after Russia annexed Crimea, the annual commemoration was banned.

While Russia has denied a people the right to commemorate an event so significant to their history, Russia has just wrapped up the biggest commemoration in its history. Last weekend Russia marked the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II with a lavish military parade and a moving march of families remembering the victims.

Now that Victory Day has come and gone, it’s a good time to reflect on this year’s commemorations. It’s especially important and revealing to do so today, when the peace and stability forged in the wake of that war are being challenged by a Russia that has unilaterally redrawn Europe's borders by force.

In Europe May 8th is known as VE Day, Victory in Europe Day. It’s the day Nazi Germany officially surrendered to the Allied Forces, marking the end of World War II. It was widely celebrated in Great Britain, France and across Europe as a day of remembrance and commemoration, with events such as concerts and parades featuring the now quite elderly veterans of the war. This year Ukraine broke with its Soviet past and held its first official “Day of Remembrance and Reconciliation” on Europe’s VE Day also, and even adopted the British red poppy as a visual symbol of war remembrance.

Russia also commemorated the end of World War II but quite differently both in tone and spectacle. Russia held a Victory Day military parade on May 9 to mark its enormous contribution to ending what is commonly known as the Great Patriotic War. Western leaders were noticeably absent from Moscow’s biggest celebration to date.

So what do these commemorations mean, and how do they contribute to our understanding of current world affairs?

To commemorate is to remember the past, but a special kind of remembering, one that happens socially, together with others. Commemorations are intended to honor, salute, and celebrate in a manner that’s by definition public. This public remembering together usually takes place in a ceremony, often formal, ritualized, always with special symbols, traditions, narratives, and the like. As shared celebrations, commemorations are based in shared experiences and collective memory. It’s how we acknowledge our shared history.

To commemorate is to remember the past, but a special kind of remembering, one that happens socially, together with others. Commemorations are intended to honor, salute, and celebrate in a manner that’s by definition public. This public remembering together usually takes place in a ceremony, often formal, ritualized, always with special symbols, traditions, narratives, and the like. As shared celebrations, commemorations are based in shared experiences and collective memory. It’s how we acknowledge our shared history.

This is significant for a number of reasons and helps us understand commemoration as a political event. While our individual experiences differ, it is some shared core of memory that forms the basis for commemorations. As memories fade, witnesses pass away, symbols and stories necessarily take on more importance as a way to keep those memories “alive.” It is here that we see how fragile memory is and how susceptible it is to manipulation and distortion, even indoctrination. Because if we recognize that collective memories require the use of symbols and narratives, who controls those symbols and narratives will control the memories and ultimately how history is remembered.

While witnesses are alive, we are fortunate to learn history through their memories. Even though I have grown up in the US, for example, my “shared history” is shaped by the stories I heard from survivors from Eastern Europe.

I emigrated from the Soviet Union. My parents were Jews caught in the war in Belarus and Ukraine. Most of their families were killed in varied and horrific ways near their homes or while serving in the Red Army. My mother and father each managed to flee and survive. But their experiences and losses never left them. Remembering the war in my family was not something done lightly or often. But we did remember it, annually, during Passover seders. As a little girl, I remember my family seders as long, gloomy crying fests. My small family of survivors, some of whom were liberated by Americans, others hidden in homes and forests, reunited every year to remember the Passover story. It was during the telling of the Jews’ exodus from Egypt and right when the cold salty soup with hard boiled eggs would hit the table that the wailing, some quiet some not, would begin. The salty soup was there to represent tears of our ancestors, but we generated plenty of our own. I cried too because everyone cried. Even at a young age, I knew that my relatives weren’t just remembering the Passover story. They were remembering their own frightful experiences of expulsion and exodus from war torn eastern Europe. Their memories became my memories.

So as May 8th approached and images started appearing in social media on Europe’s VE Day celebrations, and news agencies called for personal remembrances and photos from 1945, I was a bit horrified. The Guardian tweeted lovely photos of smiling, cheerful young people filling the streets of London. You could almost hear the champagne corks popping. How weird, I thought, that they were actually smiling. It was jarring. My parents would never have thought to celebrate the end of the war that way. That just wasn’t their experience. They didn’t have cameras to take snapshots. They were shattered and their surroundings were devastated. And they were in the Soviet Union. They didn’t feel happiness or elation or victorious. They just survived. They were “happy to be alive,” which really meant relieved that the horror might be over. Their feelings of relief and gratitude were overshadowed by profound pain, loss and trauma, forever lodged in their memory. To remember even the end of war meant to relive that pain.

So as May 8th approached and images started appearing in social media on Europe’s VE Day celebrations, and news agencies called for personal remembrances and photos from 1945, I was a bit horrified. The Guardian tweeted lovely photos of smiling, cheerful young people filling the streets of London. You could almost hear the champagne corks popping. How weird, I thought, that they were actually smiling. It was jarring. My parents would never have thought to celebrate the end of the war that way. That just wasn’t their experience. They didn’t have cameras to take snapshots. They were shattered and their surroundings were devastated. And they were in the Soviet Union. They didn’t feel happiness or elation or victorious. They just survived. They were “happy to be alive,” which really meant relieved that the horror might be over. Their feelings of relief and gratitude were overshadowed by profound pain, loss and trauma, forever lodged in their memory. To remember even the end of war meant to relive that pain.

Soviets, many of whom were also Jews, share a collective WWII experience that thoroughly traumatized the people and the nation. RT describes it this way: "Soviet victory over Nazism required the largest sacrifice in human history." Soviet citizens, particularly Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians suffered tremendously, having lost upwards of 27 million people, leaving no family untouched, between the years of 1941 and 1945. Russia deserves to honor its profound contribution to the war’s end.

But there is something deeply uncomfortable about watching Russia’s commemoration. It’s jarring but in a different way from Europe’s smiling faces. It's not just that the experiences were different and so collective memories are different. And it's not even that the lack of recognition of the millions of non-Russians from the many Soviet Republics who share in the victory and sacrifice. It's that Russia's commemoration is a public remembrance of the past which ignores critical historical facts and even distorts memories in furtherance of the state's political goals.

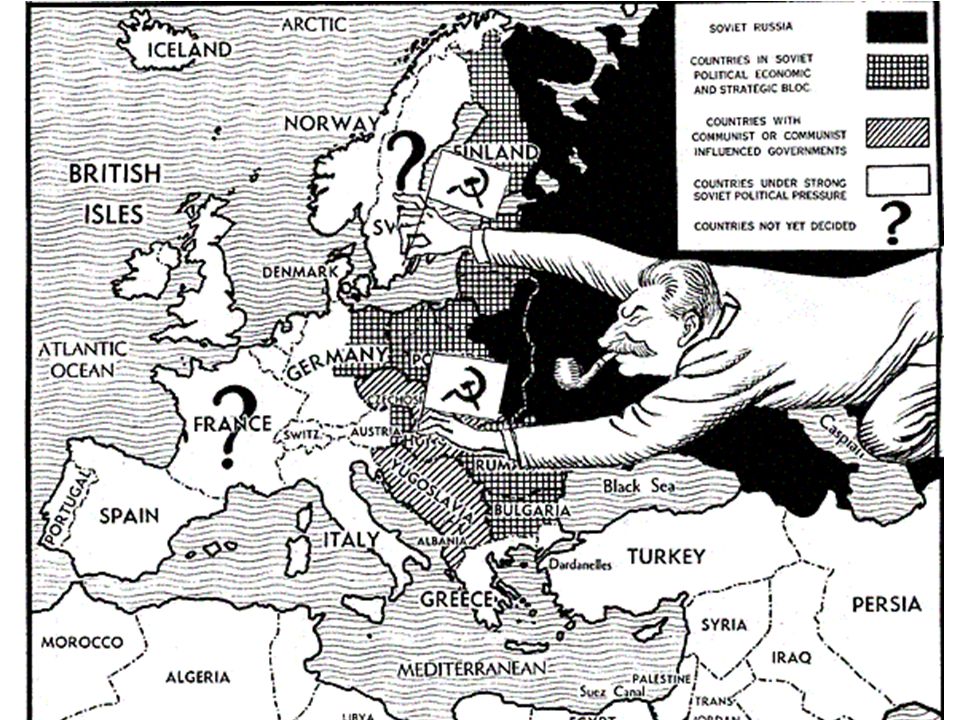

First of all, it’s impossible to ignore that the war didn’t start in 1941, as the backdrop to the Red Square stage prominently announced. WWII in fact began in 1939 with Stalin and Hitler forming an alliance to divide up Eastern European between them. So while Russians like to point out all the ethnic groups that collaborated with the Nazis in the years between 1939 and 1941, Soviet leaders were actually the first to collaborate with the Nazis. I know this is a loaded word and it should be. The Soviet Union and Nazi Germany did in fact collaborate in 1939 and that collaboration didn't just start a war; it gave Hitler the green light to march into Poland to see through his Final Solution to “the Jewish problem,” the Holocaust.

Not only did Stalin want an alliance with Nazi Germany, he sacked his own Jewish foreign minister Litvinov for Molotov to ingratiate himself further into Hitler’s good graces. Stalin knew full well that Molotov’s signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact would have a devastating impact on Poland’s Jews, the largest Jewish community in Europe.

This Pact started the march of war and the murdering of Jews across Eastern Europe, and that same war jumped the border into Soviet territory in 1941. The killing didn’t end until the Soviet Red Army, made up of Russians, Ukrainians, Jews and others, finally, after years of brutal and unbearable war, stopped the Nazis.

The Soviets ended the war they were instrumental in starting. This fact doesn’t negate their contribution of course, or diminish the fact that Russian people and soldiers suffered and fought valiantly. But it begs us to pause to consider what history is missing from Russia's Victory Day commemoration and why.

And this is where the next discomfort with Russia’s commemoration comes into play. An important function of commemorating war's end is to understand the depth of the cost of war in order to not let it happen again so easily. And yet, here we are, racking our brains trying to figure out solutions to situations remarkably similar to those in the years preceding WWII. Russia has not only annexed another state’s territory, Ukraine’s Crimea, it is now waging war in eastern Ukraine. Real war. Tanks, shells, bombs, and all the resulting death and destruction. Boris Nemtsov’s posthumous report “Putin. War,” published just days after Moscow’s Victory Day celebration, provides a wealth of evidence of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, combining in one place much of what journalists and soldiers have been telling the world for over a year.

Russia’s commemoration of the end of war, its Victory Day, was in fact a glorification of war. It was a formidable show of force, boasting proudly its numerous weapons of war through Red Square. On the one hand, the message might be a defensive one: “Nobody will ever touch us again, look at how we are protected.” But on the other hand, one can't forget that these same weapons have been used and are still being used in Ukraine by so-called “separatists” in an obvious if undeclared offensive war. Even the surface to air Buk missile system like the one that brought down flight MH-17 paraded through Red Square. And many of those who marched and were celebrated in the military parade have had a hand in the war in Ukraine and have been decorated for their participation in Crimea's annexation.

Remember the current context. Russians have been bombarded for over a year with intense round-the-clock propaganda to implant into the Russian consciousness the Kremlin narrative of a Nazi junta taking over Ukraine’s government in an American-led coup. Through direct closures of independent media outlets, severe prohibitions and penalties on protests, nonstop vilification of anti-war dissenters as “fifth column” saboteurs funded by America, Russia’s pro-democracy liberals, who want to see Putin out of office, are branded as lowlife traitors to the homeland. There are people who proudly contend Boris Nemtsov deserved to be assassinated at the foot of the Kremlin and worse. Add to this the activity and prominence of Russia’s “patriotic” groups like NOD, SERBs, and Anti-Maidan staging mass rallies with banners extolling hatred in the same breath as glorifying Putin, and you sense a kind of mass vigilantism spreading throughout Russian society like a virus.

Russia's rise of patriotism is not a popular bottom-up movement, however. This is a carefully choreographed response by a Kremlin propaganda machine that uses symbols and narratives of flag-waving patriotism, including the fervent embrace of the main symbol of war in Ukraine, the ubiquitous orange and black St. George ribbon, on everything from tanks to babies. This is probably the last major commemoration to include people who witnessed the war, veterans and survivors. As they pass, and their memories pass with them, it will be the symbols and narratives that will be left to tell the stories of history. With the Kremlin in firm control of Russia’s narrative, you can’t help but feel Putin has stolen the sacred legacy of the Great Patriotic War to prop up his brand of patriotism and policies that include even the unthinkable–war. Putinism is really just keeping him and his circle in power. It’s a patriotism grounded in fear and resentment of imagined enemies external–Ukraine, US, the West–and within. A patriotism that abhors and ruthlessly punishes dissent. And now it’s a patriotism cloaked in the Great Patriotic War too.

Against this backdrop, the parading of weapons of war before the world in Red Square–weapons we've seen on streets in Ukraine–seems at best a justification for Putin’s war in Ukraine and at worst a mobilization of the Russian people for some inevitable confrontation with the West. That doesn’t seem to fall within any common understanding of commemoration. This is something quite different.

Russia’s commemoration has moved from one whose focus was remembrance to one of showing off as a way to intimidate and worse. It remembers some history, the noble parts, while denying the uncomfortable ignoble truths. To honor the sacrifices of the past in a meaningful way means accepting history "as is," the good and the bad. Because there is always bad history. Russians have yet to claim their responsibility and reconcile with their WWII past. Instead of guiding their people through a painful but ultimately necessary process, one that would allow traumas to heal and result in a stronger nation, Russia’s leadership prefers to saber-rattle and deny their past. It’s a cheap way to boost ratings. And it cheapens the memory of Russia’s heroes, of which there were so many.