Eurasianism by definition is diverse because it argues that Russia to one degree or another has roots in both Europe and Asia, with some of its advocates stressing one and others the other. But few ever went as far in stressing the Asian nature of Russia as Erendzhen Khara-Davan whose ideas are now being discussed in Moscow.

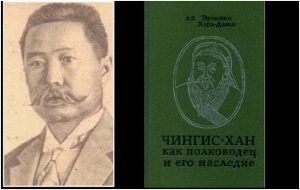

Born in 1883, Khara-Davan was a Kalmyk national democrat and enlightenment figure. In 1920, he emigrated along with the Russian White Army and settled in Yugoslavia where he earned his living as a doctor and wrote articles and books stressing the Asian nature of Russia and Eurasianism.

As Pavel Pryanikov points out in his blog today, Khara-Davan “occupied the extreme Asian position in the Eurasian movement among the White emigration. He was certain that before Peter I, Moscovy (the country that in Peter’s time started to be called Russia) had nothing in common with Europe but were part of Asia” and that the Mongol horde created Muscovy and Russian centralization” for its convenience.

According to the Kalmyk theoretician, Pryanikov says, “the Horde created Russia,” a step that he saw as historical progress. Had that not happened, Khara-Davan argued, “the pro-Moscovy’s principalities would have been swallowed up in a Western Polish-Lithuanian Rus and no Russian statehood or nation would have formed.”

If Khara-Davan is remembered at all today, it is less for his Eurasianist ideas than for his support of Hitler and his proposal at the end of the 1930s to resettle the Kalmyks, other North Caucasians and the Cossacks in the emigration in northern Mexico where they could create “a steppe autonomy” and block “American expansion to the south.”

Nothing came of that, and Khara-Davan’s cooperation with the Germans did not last long – he died in 1942 – but his ideas, according to Pryanikov deserve to be remembered because of their originality and their capacity to generate debate about Russia’s origins and also Russia’s future.

As presented in his most important book, “Chingiz Khan. The Great Conquerer” (Belgrad, 1928, 320 pages, available for online reading), Khara-Davan’s ideas are striking if far from convincing in all respects.

According to the Kalmyk Eurasianist, Russia’s “uniqueness” resides in the fact that it did not have social strata like European feudalism until the 16th century and that its cities, rather than having a special status that allowed them to develop differently than the countryside, were “bases of agrarian colonization.”

Thus, Khara-Davan argued, “there was no feudalism in Kyivan Rus’” and in Russian areas subsequently, the veche in which so many Russians even today place their faith was in fact “an anachronism” because it did not have regular meetings or form continuing representative organs.

“The feudalization of Rus took place in the Mongol period,” the Kalmyk Eurasianist said. “It involved primarily the Moscow principality, which transferred from the Horde into the service of the prince with many Tatars who brought with them a special eastern feudalism, based on the Turkic instate of tarkhanism” which is perhaps best translated as state service.

Tarkhans served the khan and everything they had and all of their status was dependent on him, Khara-Davan wrote. As a result, “Eastern feudalism did not carry within itself the democratic institutions” that Polish-Lithuanian feudalism did in the case of Western Rus with all the subsequent consequences that entailed.

Indeed, Khara-Davan said, “the Horde was a more progressive society than the Muscovite” since even under the Chingizides, the power of the khan was limited by the kurultay and later by the Islamic clergy, developments which did not extend to Muscovy which preserved the older model of society and governance.

“The organization of Russia which was the result of the Mongol yoke was undertaken by the Asian conquerors of course not for the good of the Russian people and not for the elevation of the Moscow grand principality but for the Mongols’ own interests and the convenience of administering a large conquered territory.”

Instead of the usual practice of promoting control by a policy of “divide and rule,” the Mongols imposed a single center of control, something that Muscovite rulers often followed in the future just as they accepted from the Mongols three key features of Muscovite statehood: autocracy (the khanate), centralism, and serfdom.

According to Khara-Davan, the Mongols did establish “something like an administrative hierarchy which prepared the ground for the establishment of a centralized state. And the Russian people, as the single ethnos on a defined historical-geographic space, thus owes its origins to Mongol rule.”