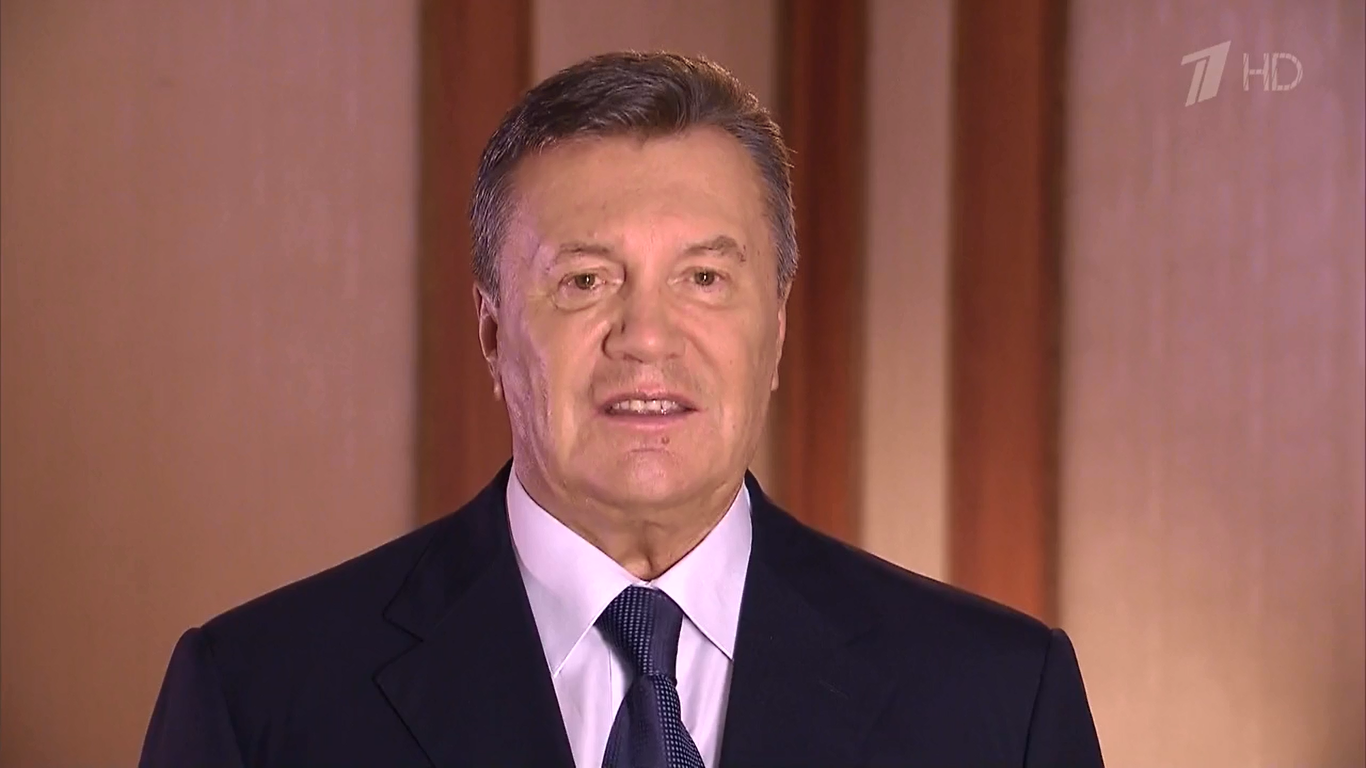

While many in the West celebrate the negotiation process between the government and the opposition in Ukraine, it is important to realise that virtually no compromise has been attempted by the authorities so far. Below I am providing a brief summary of the key ‘concessions’ made by President Yanukovych and explain what they really mean.

1. An offer to the opposition to join and even head the government.

This is a smart tactical step which pursues numerous goals. Reported by the Presidential Administration minutes after the negotiation round was over, it created a storm of indignation among the protesters who felt that even contemplating such an offer meant the opposition’s pursuit of power and betrayal at the expense of people’s expectations and sacrifice. As a result, the opposition leaders had to explain away to the people rather then present and discuss the negotiation results with them.

While it may sound as a division of power attempt to the West, it’s worth remembering that in Ukraine President can appoint and dismiss any minister (except Prime Minister) at any time. The ruling Party of the Regions has a Speaker and a strong majority in the Parliament. The Ukrainian economy is in dire straits and Russian loans, promised to resigned Mykola Azarov, will hardly come if the opposition takes the Cabinet of Ministers (well, under Azarov it was hardly guaranteed, too). In fact, a year ahead of the presidential elections, it would just play into Yanukovych’s hands to blame the opposition for any problems or undelivered promises. So, if Arseniy Yatseniuk by any chance decided to take Yanukovych’s offer, it would be totally suicidal for his political career.

2. Repeal of the ‘dictatorship laws’.

Opposition MP Lesya Orobets provided an excellent analysis of this step here. In addition, Yanukovych has not signed the law passed in the Parliament on Tuesday (January 28) yet (the condition upon which the law comes in force) and going on sick leave is a likely trick never to do this. According to one of the sources, he openly declared that he wasn’t going to sign it during the PR faction meeting on Wednesday.

3. The law on the amnesty of the detained protesters.

This law was indeed passed on Wednesday (January 29) after hours-long session in the Verkhovna Rada. Importantly, four bills were registered in the Parliament, two of which envisaged the liberation of the detained protesters unconditionally. While there were enough votes to pass one of them (according to ‘The Insider’, an independent online media, 52 Party of the Regions MPs were ready to vote for it), President Yanukovych himself arrived at the Parliament and summoned a faction meeting. After this, a bill prepared by the Representative of the President in the Verkhovna Rada Yuriy Miroshnychenko was voted in. It foresees the liberation of the detained protesters only after all streets and administrative building are freed by the demonstrators. These conditions are unacceptable to the protesters since they mean giving up effective leverage on the authorities and no guarantees against further detainments, abductions and torture. In effect, the President himself intruded in the Parliament’s work so that no consensus between his party and the opposition could be reached. Speaker of the Parliament Volodymyr Rybak conceded yesterday that Yanukovych had threatened his deputies with the Parliament’s dismissal.

All these steps are taken by Yanukovych to placate the West with seemingly democratic solutions. In fact, these are all imitations aimed at blaming the opposition leaders for derailing the negotiations. Meanwhile, detainments, crack-downs on the protesters in the region and repressions persevere.

Yanukovych’s supporters like to stress that Yanukovych was democratically elected. True, and this was the last thing connected to him which had anything to do with democracy.

Kateryna Zarembo, deputy director of the Institute of World Policy in Kyiv, Ukraine.