The 20-year-old ban on regional-level political parties, put in place when President Vladimir Putin came to power in 2001, actually turned Russian regions into political “clones” of one another (Region.Expert, September 3). Today, local civil communities in Russia’s 85 federative subjects (this includes the illegally occupied Republic of Crimea and Federal City of Sevastopol belonging to Ukraine) can try to express their interests only through federal-level parties; but these attempts are often unsuccessful because each of these parties is controlled from Moscow and pursues a centralizing policy.

Nevertheless, regionalism sometimes “sprouts” even in those parties whose opposition to the Kremlin is highly doubtful. The most illustrative example was the mass protests of 2020 in Khabarovsk (in the Russian Far East). Demonstrations erupted following the arrest of the freely elected governor from the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDNR), local native Sergei Furgal, who defeated Putin's United Russia party appointee. Protesters took to the streets carrying flags of Khabarovsk Krai—an unprecedented sight in today’s Russia.

Since then, however, the Kremlin apparently learned lessons from that incident. Anton Furgal, the son of the former governor, tried to run for the State Duma elections this year. Yet despite enjoying support from the local population, the electoral commission did not allow him to register, under several dubious pretexts, including the “incorrect filling of signature lists” (Sibir.Realii, August 13).

Some regional branches of federal parties differ significantly from their Moscow leadership. An illustrative example is the head of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) in the Komi Republic, Oleg Mikhailov, who two years ago said that Moscow was pursuing a “colonial policy” toward the regions (Region.Expert, January 14, 2019). Mikhailov was one of the leading members of the protest movement against the construction of a giant landfill in the Russian High North to receive Moscow’s surplus garbage. The Moscow leadership of the CPRF notably did not support him in those protests at that time, since it adheres to an imperial-centralist ideology. However, today, he heads the local list of the CPRF in the elections to the State Duma. Probably, Gennady Zyuganov and other central leaders of the CPRF understand that without the help of notable activists like Mikhailov, the Communists might lose all popularity in the region.

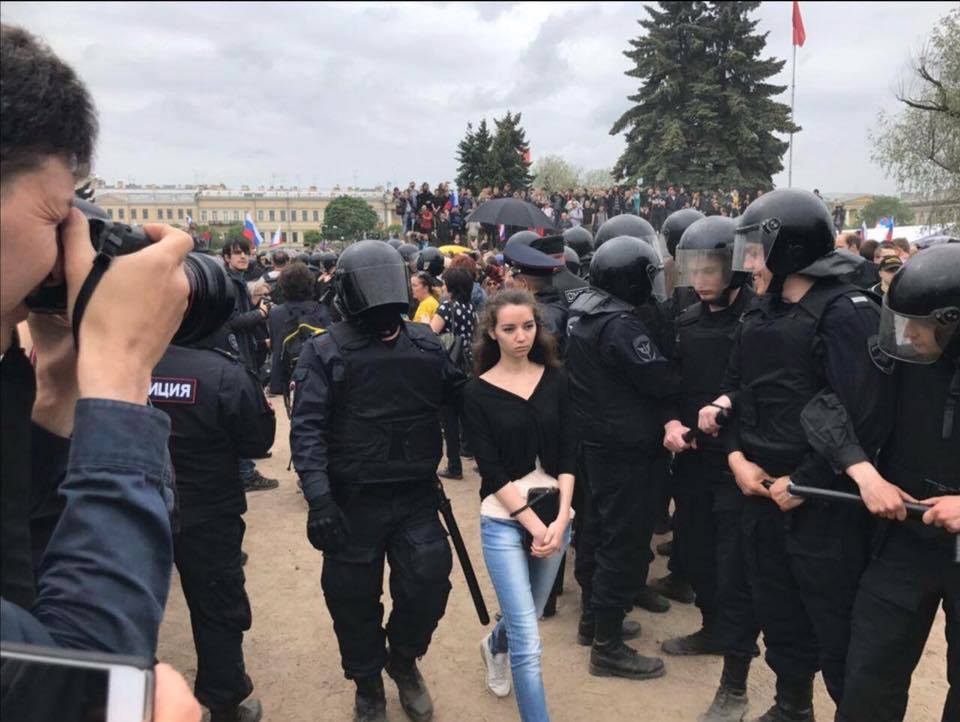

As for the opposition movement of Alexei Navalny, it is presently largely defeated: he himself is in prison, and his regional headquarters have been declared “extremist organizations,” making it impossible for them to participate in the elections. Even those politicians who were not members of Navalny’s movement, but simply participated in rallies for his release, are blocked from the elections. This happened, for instance, in Novgorod Oblast (7×7-journal.ru, August 28).

In neighboring Pskov Oblast, the prominent politician Lev Shlosberg was also removed from the elections, both to the State Duma and to the Pskov regional parliament, and for the same reason: “for supporting Navalny.” Such an accusation seems farcical—Schlosberg is a member of the Yabloko party and, thus, a political opponent of Navalny’s movement (Svoboda.org, August 26).

But perhaps the greatest absurdity was the authorities’ demand that YouTube block the recording of the pre-election debates, where one of the participants openly demanded the release of Alexei Navalny. YouTube obeyed this requirement, fearing that it might become banned from the territory of Russia. Thus, even the mention of Navalny’s name was barred in the Russian information space (Svoboda.org, September 7).

This demand for freedom for Navalny was expressed by the leader of the Russian Party of Freedom and Justice (PFJ), Maxim Shevchenko. This new faction sometimes makes liberal statements to boost its popularity, but it remains quite safe from coming under threat of removal from the elections, since its platform is actually quite close to that of the ruling United Russia. In August, in the capital of the Republic of Tatarstan, Kazan, Shevchenko participated in a roundtable on the topic of federalism. His party is trying to win over public figures in the non-Russian republics to its side, but the PFJ’s particular interpretation of federalism effectively excludes any treaty relations between the regions. Shevchenko states that the main principle of the federation is a ban on withdrawal from it (Business-gazeta.ru, August 30).

In early 2021, a group of politicians and public figures from various regions tried to register the Federative Party, which declared in favor of the principles of inter-regional treaties and of political decentralization in Russia (Svoboda.org, May 7). They hoped to take part in the Duma elections. However, their party was not allowed to register, and its leader, a deputy from Lipetsk, Oleg Khomutinnikov, was forced to leave Russia under threat of criminal prosecution.

Read More:

- Western sanctions regime must be fundamentally revised because Russia is a mafia state, Gessen says

- Moscow complains about campaign against Russian speakers in Ukraine while waging a far more sweeping one against Ukrainian speakers in Russia, Yatsenyuk says

- Moscow’s labeling of Protestant groups with Latvian and Ukrainian links ‘undesirable’ has other Protestants in Russia worried

- Ukrainian Foreign Minister reminded his Russian counterpart what Russia was called until the 18th century

- In 1991 Russia, ‘no one was ready for democracy or really wanted it’ and not much has changed, Lev Gudkov says

- Russia resembles a cemetery through which an armed man is walking, Martynov says

- Jailing innocent Crimean Tatars to insanely huge terms: a how-to guide from Russia

- Is Shoygu preparing to become Russian President?

- Putin better reflects underlying Russian values than does the opposition and his system will thus outlast both, Pastukhov says