Of the interesting debate organized by LibMod – Zentrum Liberale Moderne’s project “Ukraine Verstehen” (eng. Understanding Ukraine) around the petition submitted to the Bundestag to acknowledge the mass starvation of rural Ukrainians in the thirties, the Holodomor, as pictured in Agnieszka Holland’s “Mr. Jones” (2019), I mainly keep in mind three remarks made by Manuel Sarrazin, a speaker for eastern European politics of Bündnis 90/ Die Grünen in the Bundestag since 2018.

Most of Ukraine’s present problems are post-colonial.

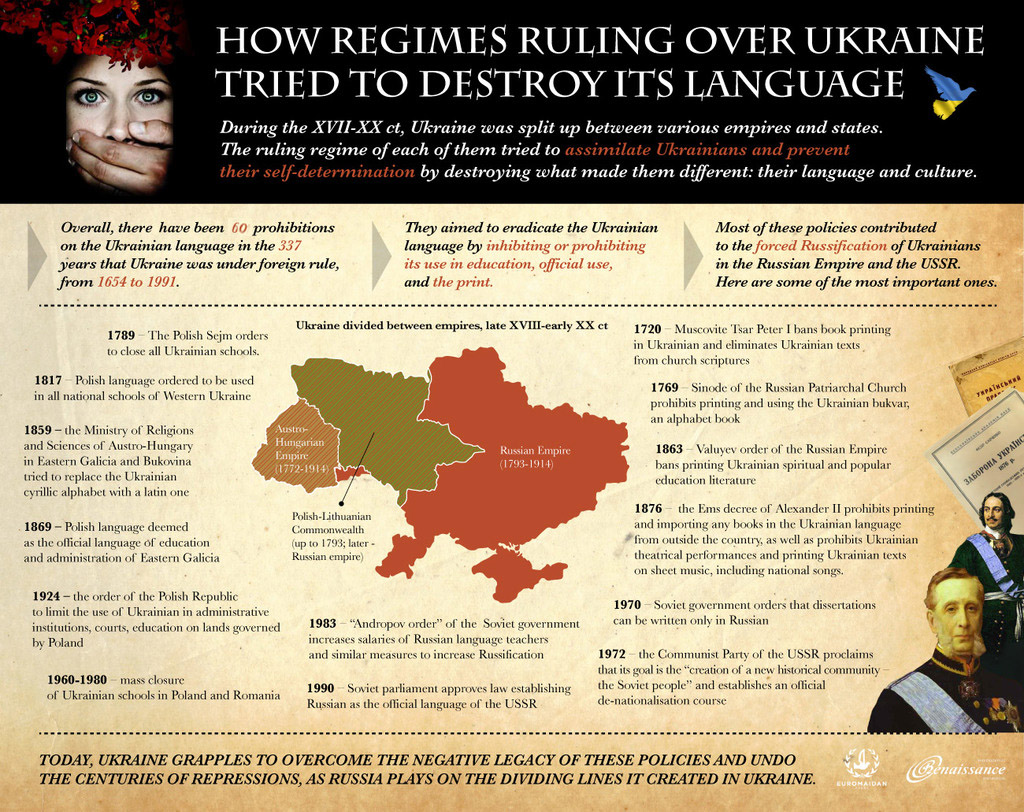

Indeed, partly because of Ukraine’s historical past: Kyivan Rus was already the cultural center of a brilliant civilization, long before the tiny principality of Muscovy even existed. The Tsars and Stalin constantly repressed all things Ukrainian, going as far as forbidding the public use of the Ukrainian language for hundreds of years.

Taras Shevchenko, a Ukrainian national treasure, was punished by forty years of forced labor in the most forbidding fortresses of the tsarist Russian Empire. Shevchenko's writings formed the foundation for the modern Ukrainian literature to a degree that he is considered one of the founders of the modern written Ukrainian language. Shevchenko's poetry contributed greatly to the growth of Ukrainian national consciousness. His influence on various facets of Ukrainian intellectual, literary, and national life is still felt to this day.

Starting in 1720, Peter I’s decree banning the printing press in the Ukrainian language and Ukrainian texts and continuing on through to 1990s, where the Russian language was granted official status by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Law, to 2014 when the Ukrainian language has been banned in Crimea, and regions of occupied Luhansk and Donetsk. Between 1914 and 1916, a huge Russification campaign was started by Nicholas II, and the prohibition of the Ukrainian word, education, and church took place.

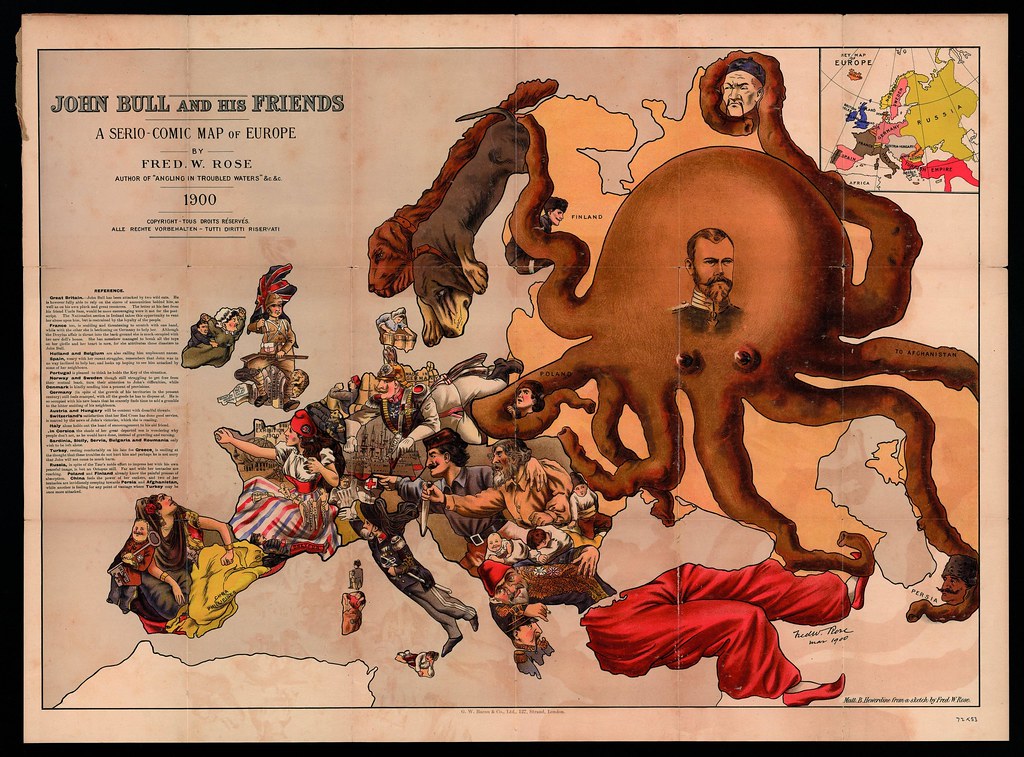

Comparing French and Russian colonialism

In order to compare colonial attitudes, [highlight]the French, for their part, established a highly centralized administrative system that was influenced by their ideology of colonialism and their national tradition of extreme administrative centralism.[/highlight]

Their colonial ideology explicitly claimed that they were on a "civilizing mission" to lift the benighted "natives" out of backwardness to the new status of civilized French Africans.

For example, potential citizens were supposed to speak French fluently, to have served the French meritoriously, and to have won an award, and so on. If they achieved French citizenship, they would have French rights and could only be tried by French courts, not under indigénat, the French colonial doctrine and legal practice whereby colonial "subjects" could be tried by French administrative officials or military commanders and sentenced to two years of forced labor without due process.

However, since France would not provide the educational system to train all its colonized subjects to speak French and would not establish administrative and social systems to employ all its subjects, assimilation was more an imperialist political and ideological posture than a serious political objective.Most of Western Europe follows Russia’s example in refusing Ukraine the right to being a nation.

As a colonialist power, the French were no better than the Russian Empire and it is quite revealing that, in spite of the wounds left by the Algerian war on the French psyche, [highlight]the present Algerian government is hardly ever accused of nationalism by the French.[/highlight]

In fact, most of Western Europe follows Russia’s example in refusing Ukraine the right to being a nation.

When today’s Germany thinks of Ukraine, this thinking is heavily influenced by Germans who themselves have lived in the GDR or who transmitted to their descendants a lot of what can be considered a “sovok” mentality (“sovok” which has come to be considered an insult, describes a provincial mentality heavily influenced by the Soviet ideals).

In the GDR, Ukraine as a bearer of a distinct identity was a total taboo. The recent controversy triggered by ex-chancellor Schröder contemptuously brushing off criticism by calling the Ukrainian Ambassador to Germany “a dwarf” echoes my baba’s protests about being constantly called “little Russian,” which she correctly saw as an insult. On the other hand, Mr. Melnyk, the Ukrainian Ambassador to Germany is to my knowledge taller than Schröder, if anyone is comparing sizes.

Identity reconstruction derided as "Ukrainian nationalism"

Ukraine must restore its poetic and musical language to its glory and free it from Russicisms imposed for centuries by Tsarist imperial decrees and secret commissions.

Such work of Identity Reconstruction requires intelligent patriotism.

What in Western Europe is considered fascism, in Ukraine, means going back to the roots of Ukrainian identity, the regaining of once-lost freedom from imperial and Soviet shackles. [highlight]A patriotic identity is being mistaken for nationalism.[/highlight] It has no ties to far-right movements gaining attention, footing, and power in the Western world, especially in the US as of lately.

The swastika originally was not a Nazi symbol until the 1930s, but a symbol of auspiciousness and good luck in Western Europe. As a symbol, it is a sign of divinity and spirituality in Indian religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Because of World War II and the Holocaust, many people in the West still strongly associate it with Nazism and antisemitism. As such, this is another post-colonialist wound: being denied identity symbols for reasons specific to the colonialists.

Genocide

Mr. Sarrazin’s further remarks opened up also new and interesting avenues for genocide research and discussion around this term.

Research and terms of genocide have considerably broadened as of lately, particularly in the field of international law. As a concept introduced by Raphael Lemkin, genocide has a far broader definition today.

[highlight]Genocide defined is not a spontaneous hate outburst, but an organized crime with intent. [/highlight] As the Soviet archives gradually open up in the former Soviet republics and especially in Ukraine, we receive more proof of genocidal intent vis-à-vis all the tragic events that happened in Ukraine during the Soviet rule.

If mass starvation, the Holodomor, was essentially targeted towards the Ukrainian peasantry, the intelligentsia was likewise removed from the Soviet path, as more previously unknown mass graves are being discovered in Ukraine every day.

An additional admission of guilt is the proof of systematic destruction of the civil registers of starved villages between 1932 and 1937, which showed that there was a sudden demographic deficit of eight million Ukrainians in the regions affected by Holodomor. No demographic census has been published until 1938. Many employees of the National Census Bureau, as well as the director, were shot. All of the above, including the deliberate demographic change, are today considered as markers for Genocide.

People from all around the Soviet Union were given houses and lands of the starved Ukrainian farmers, in some cases new owners entering their new premises while the past owners were still dying. Planned ethnic repopulation is one of the markers for genocide intent.

If I only refer in this article to Mr. Sarrazin that does not at all mean that, other debate speakers were not interesting. It was Mr. Sarrazin’s call to reconsider both the notions of Genocide itself as well as intent of genocide correspond to the conclusions I had drawn recently by reading Drelingas v. Lithuania conclusion:

A summary by J. Zilinskas for the blog of the European Journal of International Law:

“The European Court of Human Rights on 12th of March 2019 issued a judgment in the case of Drėlingas v. Lithuania (Application no. 28859/16). The case at the ECHR was considered under Article 7 and focused on the principle of nullum crimen sine lege. However, in broader terms this case dealt with the definition of genocide and the protected group issue in particular. This judgement continues a series of judgements related to Soviet mass repressions in the Baltic States after they were occupied and annexed by the Soviet Union and “sovietised” in a most brutal way from 1940 up to Stalin’s death in 1953. First of all, it challenges a widely accepted view, that Soviet Union and communist regime repressive policies cannot be considered as “genocide” because they were imposed on the basis of social and political rather than national ethnic attitude. Second, it brings us back to the discussion, started by the father of the concept of genocide – Raphael Lemkin – whether protection of political groups must be included in the genocide ambit, this time through the back door. Third, with the concept of crimes against humanity reserved for an attack against a civilian population, it looks that those who are resisting an inhumane regime as brothers in arms may still be an object of protection within the bigger picture.”

Newly defined intention markers the International Court of Justice at The Hague with the court’s decision in the case of Gambia v. Myanmar of this year broaden the intention markers of Genocide, as we know them:

This is a very significant decision in legal terms, for the rights of the Rohingya and in the fight against impunity. Relying on the Belgium v Senegal case at the ICJ (where the Convention Against Torture was the source of obligations), in the words of the court, “It follows that any State party to the Genocide Convention, and not only a specially affected State, may invoke the responsibility of another State party with a view to ascertaining the alleged failure to comply with its obligations erga omnes partes, and to bring that failure to an end.” (para. 41, 23 January Order).

The Court observed that, in accordance with Article I of the Convention, all States parties thereto have undertaken “to prevent and to punish” the crime of genocide. Article II provides that “genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

It will be some years before the ICJ makes a final ruling on Gambia’s genocide allegation. However, in the interim it has ordered Myanmar’s government to take emergency measures to protect the Rohingya and report to the ICJ on a six-monthly basis on its related actions. The first report is due at the end of May.

We are witnessing a considerable expansion of the concept of genocide in the field of international law. In a century filled with Genocides, it should also influence our reflection of the past. With new markers of definition for genocidal intent, we should now also be concerned with genocide prevention.

Read also:

- The Man and the Nation nobody expected: Andrei Sheptytskyi and Ukraine

- Orientalism reanimated: colonial thinking in Western analysts’ comments on Ukraine

- Postcolonial syndrome, or Why do revolutions occur one after another in Ukraine?

- Ukraine and the Kremlin’s myth of the “polite” invader

- Nazi dreams of an enslaved Ukraine: the blind spot of Germany’s historical memory – Timothy Snyder

- How Moscow hijacked the history of Kyivan Rus

- Taras Shevchenko. The case of a personal fight against the Russian Empire

- A short guide to the linguicide of the Ukrainian language | Infographics