The research paper "Resilient Ukraine: Safeguarding Society from Russian Aggression" by Mathieu Boulègue and Orysia Lutsevych issued by Chatham House discovers Russia's drivers of negative influence on Ukraine, Ukraine's current approach to conflict resolution, analyses four cases of successful responses to social disruptions in Ukraine, and formulates recommendations how to improve resilience to Russian aggression.

Here we publish some key finds of the paper.

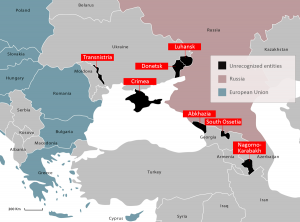

Since Ukraine's Euromaidan Revolution that toppled pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych from power in early 2014, Russia has deployed a range of measures – short of an open declaration of war – to undermine Ukraine’s European and Euro-Atlantic aspirations. Russia's full-spectrum war against Ukraine exploits domestic vulnerabilities to sow chaos and challenge the state.

Fortunately, despite Russia’s aggression, economic pressure, and information war, Ukraine has persevered as an independent state thanks to its resilience and determination to defend its own future. Moreover, Ukraine has largely maintained its democratic reforms thanks to its resilience and determination to decide its own future. The country is gradually developing the capacity of its state institutions and civil society to address the political and social consequences of Russian aggression.

Kremlin's levers of influence in Ukraine

The Kremlin seeks to exploit these vulnerabilities to promote polarization and encourage a clash between Ukraine’s citizens and its governing elite by taking military action, manipulating the corruption narrative, supporting pro-Russia parties, and fuelling religious tensions through the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) that still controls a large share of Orthodox parishes in Ukraine.

The corruption narrative was prominent during the 2019 presidential election and Russia continues to use it against Ukraine. Transparency in public affairs has increased across the board in Ukraine and the volume of investigative reporting has soared.

However, some content violated international standards of investigative reporting. Moreover,

All these factors have contributed to [highlight] an increased perception of corruption.[/highlight] The oligarch-controlled media have vilified then-President Petro Poroshenko and the ruling elite.

The Kremlin clearly endorsed the Opposition Platform – For Life (OPFL) during the 2019 electoral campaigns. The party eventually made it to the Parliament, and its deputy head who owns several several TV channels and a business empire, Victor Medvedchuk, has actively pushed the Kremlin's agenda for Ukraine including the idea of autonomy for Donbas, for Kyiv to directly negotiate a peaceful solution with the Russia-backed separatists, and a nationwide referendum on a future peace deal.

In the religious sphere, Russia remains influential through the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). The situation has escalated after the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople signed a decree granting autocephaly to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) in early 2019.

Societal polarization and the government's efforts to address Russian aggression

With no clear way to end the armed conflict, there is a growing risk of societal polarization. Conflict resolution particularly requires engagement with Ukrainians in the non-government-controlled areas (NGCA).

‘Conflict resolution’ and the ‘safe reintegration’ of Donbas have become new catchphrases in domestic political discourse. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has demonstrated a genuine willingness to achieve peace and has applied a human-centric approach to managing the conflict. However, his strategy is constrained by a lack of clear actionable steps, an absence of effective coordination between various agencies, and reluctance to engage civil society in decision-making.

Zelenskyy desired to reboot international diplomacy around the Donbas. The last round of the revived Normandy Format discussions in December 2019 did not deliver a breakthrough. It led to further exchanges of prisoners, the creation of three new priority disengagement areas by March 2020, however the recommitment to the ceasefire did not last long, 11 Ukrainian servicemen were killed in the east in January 2020.

Case studies

Societal cohesion is a necessary element of resilience. Currently, [highlight] weak civic agency is challenging this cohesion,[/highlight] with just 10% of the population regularly participating in civil society and few opportunities for the public to take part in decision-making at the local level.

This is particularly the case in the southeast and is reflected by low levels of trust in authorities.

Low levels of media literacy among Ukrainians leaves the country vulnerable to manipulation and disinformation. In this context, the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX) has been implementing media literacy courses through the Learn to Discern in Schools program since 2015 and the program has so far had good results.

Participatory politics supported by local media is crucial to societal resilience against disinformation and information manipulation. The Kharkiv-based independent sociopolitical media group Nakipelo is used as a platform to raise citizen concerns about local problems and voice them to the local administration.

The Legal Hundred (Yurydychna Sotnia) is a Ukrainian non-profit organization working on veteran affairs and issues related to defense and security since 2014. The organization is playing a leading role in the process of reforming the legal framework that defines the status of veterans and conflict-affected civilians.

In 2016, the Ukraine Crisis Media Centre (UCMC) engaged museums in small cities – including some cases close to the line of contact as well as displaced museums from Donetsk and Luhansk – in a thought-provoking exercise about their own development and role in the community. The project team ensured a wide range of voices were heard: local historians, history teachers, children, and communities.

Areas of focus could include promoting the resilience approach, supporting independent media, strengthening cognitive resilience, and prioritizing social cohesion.

Read the full text of the research online.

Read more:

- Kremlin lambastes alleged Ukraine's deviations from Minsk and Normandy processes

- Kozak-Yermak plan on Donbas: The fine print

- Shady agreements legitimizing Russia’s puppet “republics” likely signed in Minsk

- Russian-occupied Crimea: Lessons of hypocrisy

- What if? Hybrid War and consequences for Europe (part 1)