The Ukrainian state’s strategy concerning the more than 2 million citizens who remain in Crimea is this: Ukraine considerers all of them its own citizens, despite that fact that the lion’s share of these people was forced, under coercion, to take on the citizenship of the occupying country. After the de-occupation of the peninsula, Ukraine guarantees that it will not take any action against any except well-known collaborators.

However, while the liberation of Crimea remains distant, the people who remain under occupation and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) from Crimea require real help immediately. What kind?

Aid for political prisoners

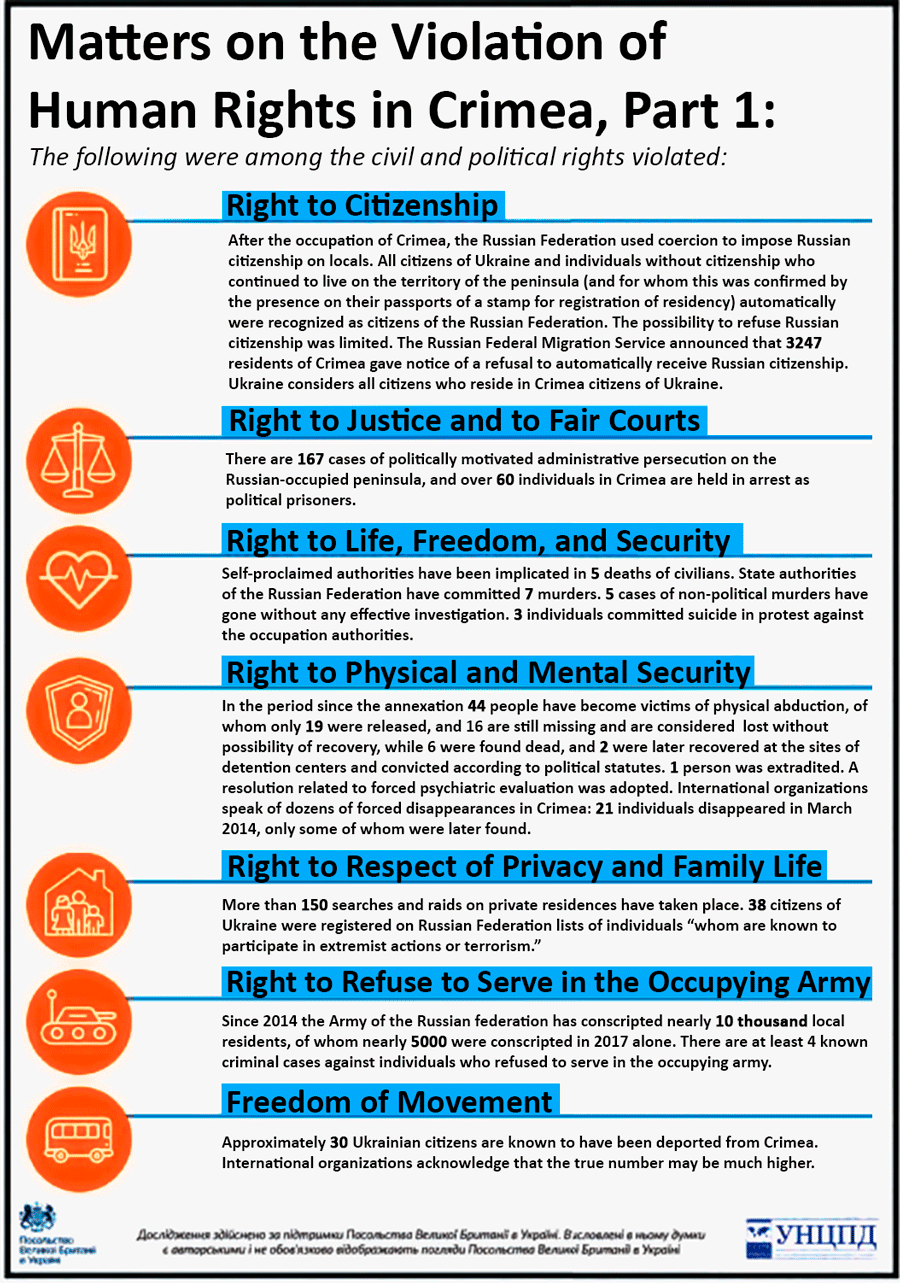

Above all Ukraine must support its own compatriots whom the occupation authorities persecute for their political positions, such as those who refuse to recognize Crimea’s annexation.

Today over 60 individuals in Crimea are imprisoned for political motives, the overwhelming majority of whom are Crimean Tatars who lead a peaceful resistance to the occupation authorities. One-hundred children remain without fathers.

“97 million Hryvnia are assigned in Ukraine’s budget for helping political prisoners and their families,” explained Yusuf Kurkchi.

However, though MinTOT together with expert support has drafted legislation which will become the basis for the establishment of a Fund for aid for political prisoners, this draft legislation has until now remained stuck in the Verkhovna Rada.

Limited administrative services

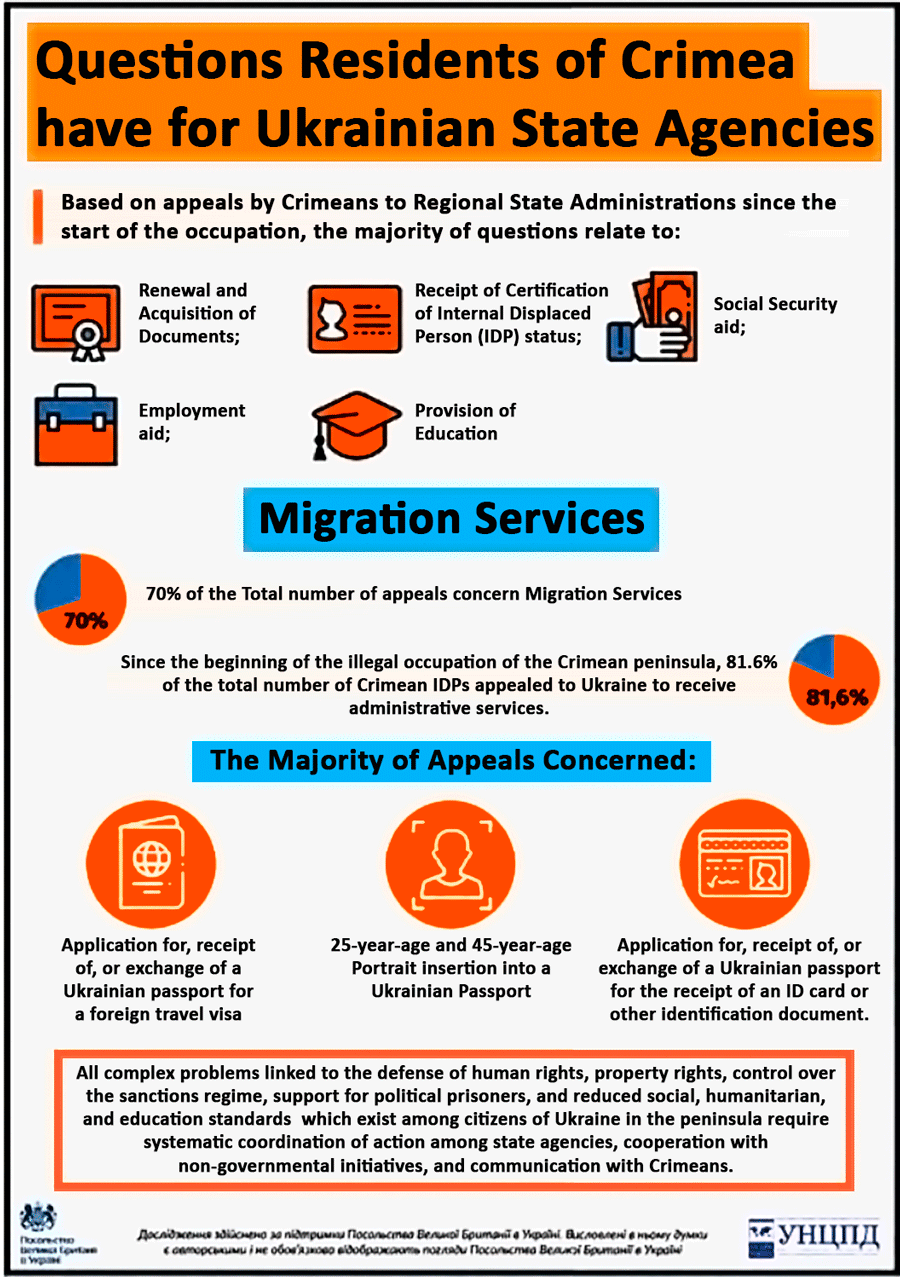

The mass of Crimeans and IDPs from Crimea require elementary things – the timely and effective provision of administrative services. This has, however, become no small problem for Ukraine throughout four years since the annexation of the peninsula by Russia.

In her words, one of the most pressing concerns is the provision of migration services (70% of the total number of appeals relate to this).

From the beginning of the illegal occupation of the Crimean peninsula, 81.6% of the total number of Crimean IDPs appealed for the provision of administrative services. The majority of these appeals regarded application, receipt or exchange of passports; the insertion of personal photographs into the passport at age 25 and 45; application for ID cards, or application for different forms of social security payments.

Clearly, Tyshchenko concludes, there is an urgent need to establish a sufficient number of administrative service centers in the region adjacent to the occupied peninsula.

Movement over the Crimean isthmus

As the report explains, despite the only way to get to mainland Ukraine from Crimea being driving after public transport was severed, residents of Crimea are still mobile.

According to data provided by the National Police, over 2.5 million individuals and 410,000 vehicles crossed the line of demarcation between mainland Ukraine and the Crimean peninsula.

To better understand: in 2013, Crimea's population was only 1.97 million people.

“Believe it or not, the goal of these crossings is not to go to a store, but to solve problems: to issue a birth certificate to children, to receive an external passport, to insert photographs at reaching such an age and so on. This is a link which binds the citizens of Ukraine in Crimea with their state,” Yusuf Kurkchi said.

“But it is very common that overviewing documents is all the state does. Our task is to bring the centers of administrative services closer to the people of Crimea,” the Deputy Head of MinTOT explained.

Unfortunately, administrative border checkpoints are not very convenient. For example, the border guard must needlessly consider whether to drink his bottle of water or wash his hands with it, because there is no water available at the checkpoint and he must instead bring it with him from the “mainland.”

Crimeans are not able to ignore the striking contrast between Ukrainian checkpoints on the administrative border and the well-furnished Russian checkpoints.

Education and healthcare

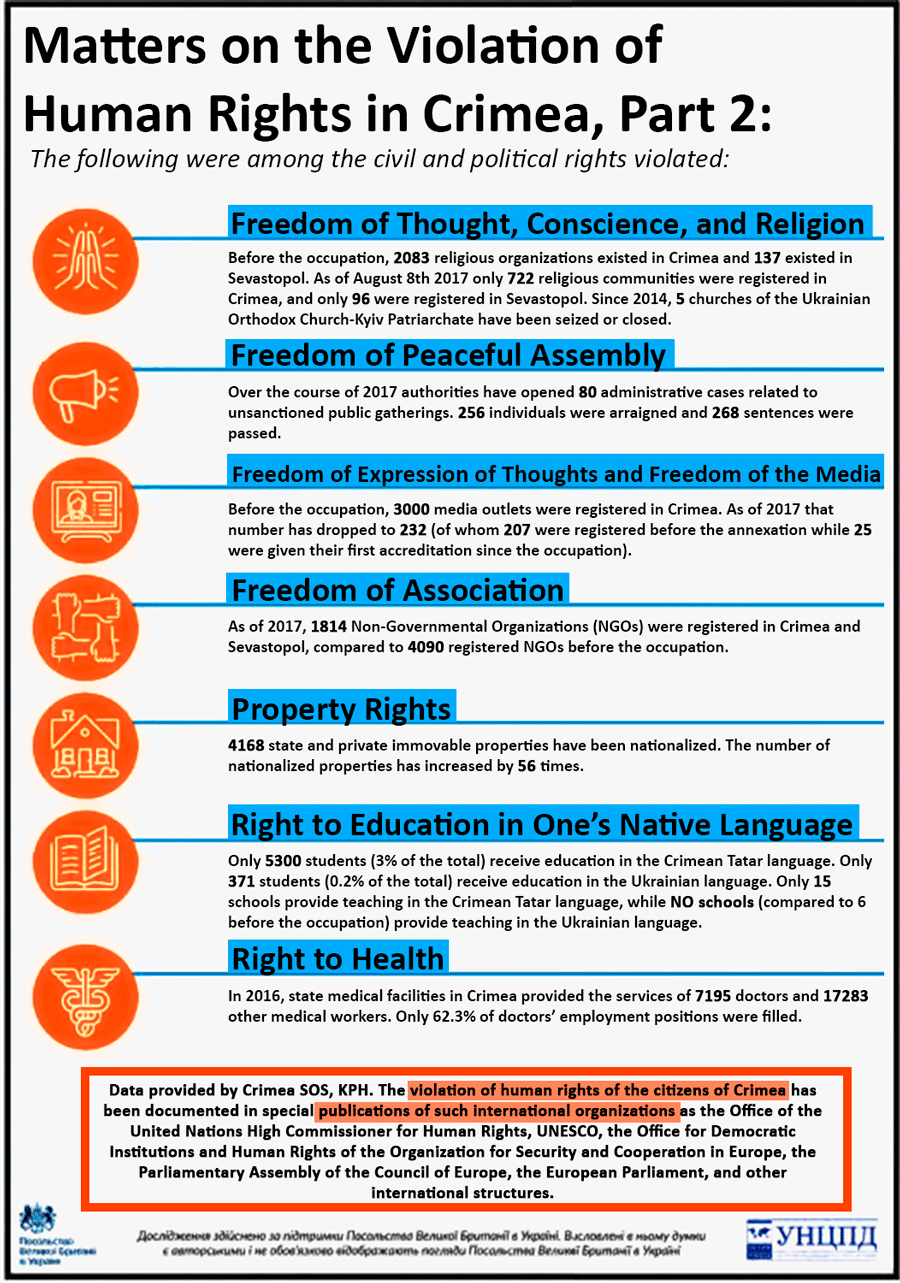

During the presentation, Yuliya Tyshchenko also outlined the different spheres of services which the state gives its Crimean residents. She separated out education from the rest.

Education, the analyst explains, is one of those few sectors where the action plan for Crimeans wishing to study in Ukrainian universities is clearly defined.

In contrast to the sphere of education, according to Ms. Tyshchenko, “the allocation of medical services is a ‘terra incognita’: even in the context of medical reform no one has offered an answer to the possibility of medical services for residents of Crimea.”

Lack of experience and countless gaps

How can the activities of state authorities become systematic and effective in the duel with Russia over Crimeans and the Crimean peninsula?

Andriy Duda, a Ph.D. in State Management, argues objective challenges derive primarily from Ukraine’s lack of experience connected with occupied territories.

“The world generally does not have much experience with creating methods of action for state authorities with regard to occupied territories. The experiences of Georgia, Cyprus, Transnistria, the former Yugoslavia all relate to small territories which cannot compare to the scale of challenges which Ukraine has encountered in the occupation of Crimea,” Duda explained. “Therefore Ukraine cannot benefit from these experiences.”

At the same time, the expert noted the gaps which for four years have not been filled. Importantly, Ukraine still has not reformed its state agencies to the new conditions, and they remain dependent on old legislation and normative bases.

As an example, Duda named the existence of a representative of the President of Ukraine to the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the partial functions of monitoring of human rights in Crimea, which belong to the authority of the Verkhovna Rada’s Ombudsman. “This creates an incorrect picture of management, a duplication of functions, a redundant waste of resources,” the expert from the UICPR explained.

“There are no ‘points of entry’ of information nor are there agreed ‘points of issuance’ for management decisions. But such ‘points’, as recognized, must be within the MinTOT,” Duda said.

Today, according to expert conclusions, the functional workload for MinTOT does not match the resource base provided to the ministry by legislation

Read more:

- The Crimean Tatar Palace and other historic sites Russia is destroying in occupied Crimea

- Military base instead of a resort: Crimea four years after the occupation

- Ukrainian taxi driver tortured and jailed to prove Russia’s “Ukrainian saboteur” scam

- PACE urges Russia end support to illegal armed groups in Donbas, cease repressions in Crimea

- Crimean court sentences activist who flew Ukrainian flag in gravely falsified trial

- Uprooted Crimean Tatar Restaurant Finds New Home in Kyiv

- New documentary: “A struggle for survival of the indigenous people of Crimea”

- How falling for Putin’s Crimea narrative will feed Russian expansionism

- Russian occupiers now hold at least 70 political prisoners in Crimea

- UN report condemns Russia over human rights abuses in occupied Crimea

- Crimea remains Ukrainian despite annexation