Almost immediately after signing the “Memorandum on Security Assurances in Connection with Ukraine’s Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons” (commonly referred to as the Budapest Memorandum) in Budapest, Hungary on 5 December 1994, then-President of Ukraine Leonid Kuchma (1994-2005) commented, “If tomorrow, Russia goes into Crimea, no one will raise an eyebrow. Besides… promises, no one ever planned to give Ukraine any guarantees.”1

Reading these words today makes them seem almost prophetic; in 2014, twenty years after the signing of the Budapest Memorandum, Russia annexed Crimea after a stealth military operation and began infiltration of two regions of Ukraine, Donetsk and Luhansk. Ukraine is now the source of much geopolitical tension in Europe, causing structures such as the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to shift their positions on a number of issues and security policies. The United States is also heavily invested in the resolution of the conflict(s) between Ukraine and Russia, as an emerging aggressive power coming from Russia threatens world security and the world order.

However, the Budapest Memorandum, at first glance, was signed to prevent anything like the above-described scenario from happening, as its text specifically highlights the territorial integrity and political independence of Ukraine and the co—signatories of the Memorandum – the Russian Federation, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom – affirmed, confirmed, and reaffirmed their agreement to uphold Ukraine’s independence, sovereignty, and its existing borders.

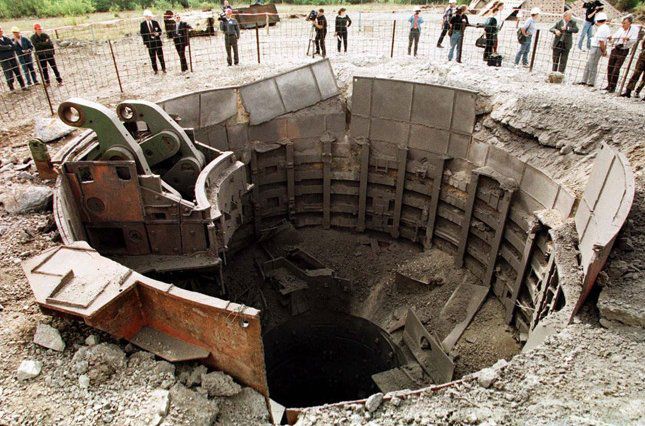

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine inherited strategic and tactical nuclear missiles, making it the third-largest nuclear power in the world behind the US and Russia. (Most Ukrainians were not aware of this fact in 1994.)2 Belarus and Kazakhstan also inherited considerable amounts of nuclear power and technology from its existence within the Soviet Union, and both Belarus and Kazakhstan signed similar memoranda on 5 December 1994 to get rid of their nuclear arsenals and join the non-proliferation movement.3 The nuclear arms held in Ukraine were under the ownership of Ukraine in terms of territory, but the controls and codes for launch or operation of the nuclear technology were inherited by Russia. Therefore, Ukrainian missiles were transported to Russia, where they faced a fate determined and brokered by Russia, or they were destroyed altogether.4

In the text of the Budapest Memorandum, there are six confirmations that each Head of State endorsed with their signatures.

1. …reaffirm their commitment to Ukraine, in accordance with the principles of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, to respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing borders of Ukraine;

2. …reaffirm their obligation to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine, and that none of their weapons will ever be used against Ukraine except in self-defence or otherwise in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations;

3. …reaffirm their commitment to Ukraine, in accordance with the principles of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, to refrain from economic coercion designed to subordinate to their own interest the exercise by Ukraine of the rights inherent in its sovereignty and thus to secure advantages of any kind;

4. …reaffirm their commitment to seek immediate United Nations Security Council action to provide assistance to Ukraine, as a non-nuclear-weapon State party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, if Ukraine should become a victim of an act of aggression or an object of a threat of aggression in which nuclear weapons are used;

5. …reaffirm, in the case of Ukraine, their commitment not to use nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear weapon State party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, except in the case of an attack on themselves, their territories or dependent territories, their armed forces, or their allies, by such a State in association or alliance with a nuclear-weapon State;

6. …will consult in the event a situation arises that raises a question concerning these commitments.5

In exchange for these “affirmations”, Ukraine gave up its entire nuclear arsenal, the Ukrainian government received financial aid from the US, energy supplies from Russia at a discounted price, and slightly closer ties to the Western World.6

The most coveted feats of the Budapest Memorandum, however, were the security guarantees that were promised to Ukraine. At the time, this semblance of security for a newly independent state, after decades of Cold War relations with the outside world, was priceless. Today we know that these promises were not kept and Ukraine’s security, since the beginning of Russia’s aggression in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, is not guaranteed. Russia has violated the Budapest Memorandum and the co-signatories, in keeping with the promises, are obliged to react.7

What was Ukraine trying to achieve in signing the Budapest Memorandum?

Indeed, out of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine – Ukraine faced the most difficult road to the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which each country joined only after signing their individual Memorandums.8 After the world had seen two world powers face off with nuclear weapons, threatening to destroy one another and the entire world, during the Cold War, a state had to declare itself as non-nuclear to join the new world order led by America and its “non-proliferation diplomacy”.9

The prolific American diplomat Henry Kissinger wrote in his book Diplomacy, “The nuclear age turned strategy into deterrence, and deterrence into an esoteric intellectual exercise.”10 Kissinger also explains that American leaders were concerned about “the problem of multiple triggers” for nuclear power around the world posed a challenge for American foreign policy, and American leaders were therefore determined “to avoid being forced into a nuclear war against their will.”11

This stance, taken on during the nuclear age of the 1950s-1960s, explains America’s approach to non-proliferation following the collapse of the Soviet Union. To avoid the “multiple triggers” problem, to carry out effective deterrence, and to create unified control of nuclear capability, America had to broker deals with countries such as Ukraine to become non-nuclear. In America’s view, the only way to do this was to have trilateral negotiations with both Ukraine and Russia, as America still viewed Russia as the guarantor of security in the region.

“In the initial periods after the proclamation of Ukrainian independence, the US essentially pursued a ‘Russia first’ policy and concentrated most of its attention on Russia. Ukrainian concerns were largely subordinated to US concerns about nuclear proliferation,” wrote Stephen Larrabee for Harvard Ukrainian Studies’ publication of Ukraine in the World.12

In addition, Stephen Pifer comments, “Nothing in the post-Soviet space commanded more attention from the Bush 41 and Clinton administrations than making sure that the Soviet Union’s demise did not increase the number of nuclear-armed states.”13

Therefore, America’s approach to Ukraine in its immediate post-independence years and the post-Soviet world as a whole was two-pronged:

- forge closer ties to Russia;

- nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament.

Accordingly, in keeping with its role, the US had financial and reform assistance to offer Ukraine in exchange for helping complete its non-proliferation agenda.

While Sherman Garnett, writing for Arms Control Today, views the US policy toward Ukraine in the 1990s as successful due to its “marriage of US nuclear proliferation policy with broad-based policy that supported economic and political reform and [addressing] Kyiv’s security concerns”14, he also remarks that “it would only be a slight exaggeration to say that US policy toward Ukraine before mid-1993 could be summarized as being absolutely right on nuclear issues and absolutely wrong on everything else.”15 Ukraine might agree.

Ukrainian diplomat Volodymyr Vasylenko once proclaimed, “By being a nuclear power, Ukraine could not have full independence.”16 Then-Prime Minister of Ukraine Leonid Kuchma echoed the concerns of Vasylenko, with his understanding that “a nuclear-armed Ukraine would not only justify Russian pressure and intervention but would also isolate the country from the West.”17

Ukraine had the technical capabilities to work toward establishing operational control over the weapons located on its soil, but its economic problems could not ignored.

Upon gaining its independence, Ukraine went through the nuances of state-building from scratch with very little money and had no use for nuclear weapons or nuclear power (especially after the Chornobyl nuclear disaster in 1986) – except as a bargaining chip.18

“The greatest threat to Ukraine’s independence is not military but economic,” wrote Larrabee.19 Failure to address economic instability in the country led inflation to reach 10,000 percent a month at one point in time and threatened economic collapse.20

It ultimately needed both political and economic assistance from the outside address its internal turmoil, which included the threat from Russia on its Eastern border.21

Larrabee observed, “Many Ukrainian officials feared that if Ukraine gave up nuclear weapons, the US would no longer pay attention to Ukraine.”22 Leading up to 1994, there were widely publicized debates in the Ukrainian parliament over whether the country should keep the nuclear weapons for its own security reasons.23 Polls even showed that while a majority of Ukrainian may have considered Russian policy towards their country as aggressive (even in 1992-93), only one-third of the population favored “retaining nuclear weapons as a deterrent.”24

The Ukrainian parliament voted on November 16, 1993 to accede to the Non-Proliferation Treaty and attached severe conditions to its ratification of the START I Lisbon Resolution, a precursor to NPT accession.25

Moscow naturally had problems with Ukraine joining a major international regime and world order such as the one espoused by the Non-Proliferation Treaty. As Russian troops entered Crimea and poured into Eastern Ukraine in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was quick to remind the world that it was now Russia which was on the list of one of the most powerful nuclear nations in the world, and not its neighboring countries as was once the case.26

Writing in Foreign Affairs, John Edwin Mroz and Oleksandr Pavliuk emphasize, “Ukraine has ample reason to suspect Moscow’s long-term intentions.”27 It was clear as early as 1939 what those intentions were. In the book A Difficult Neighborhood, John Besemeres writes, “Moscow regards its territorial acquisitions under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, whereby Hitler and Stalin divided up Eastern European countries between them, as still valid.”28

This is important to consider because for Russia, the non-nuclear status of Ukraine, or Belarus and Kazakhstan, was not of utmost importance -

In being allowed to join decision-making on a multilateral issue involving Ukraine, Russia marked its territory. Up until 1997 Russia has refused to negotiate the exact borders between itself and Ukraine. In the period leading up to the signing of the Budapest Memorandum and for some time afterwards, the Russian parliament did not annul its 1993 resolution declaring Sevastopol a Russian city, nor did it cease its orders to review the 1954 “transfer” of Crimea from Russia to Ukraine.29 Zbigniew Brzezinski once noted, “Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire.”30

Of even more concern to the US is that a truly independent Ukraine transforms the geopolitics of Europe for the better, but the reincorporation of Ukraine into a Russian-dominated sphere if influence would be devastating for European security as a whole.

The largest and most important security organization presiding over both Europe and the United States is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

The 1997 “Charter on a Distinctive Partnership between the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and Ukraine” reads much like the text of the Budapest Memorandum and includes stronger language. The Charter includes five chapters that outline the potentials and limits of the relationship between Ukraine and NATO, including recognizing Ukraine’s security as critical for building a stable, peaceful, and undivided Europe.

The Charter addresses the Budapest Memorandum directly in stating, “NATO welcomes and supports the fact that Ukraine received security assurances from all five nuclear-weapon states parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) as a non-nuclear weapon state party to the NPT, and recalls the commitments undertaken by States and the United Kingdom, together with Russia, and unilaterally, which took the historic decision in Budapest in 1994 Ukraine with security assurances as a non-nuclear weapon state.”31

The document also states that NATO Allies support Ukrainian “sovereignty and independence, territorial integrity, democratic development, economic prosperity and its status as a non-nuclear weapon state, and the principle of inviolability of frontiers, as key factors of stability and security in Central and Eastern Europe and in the continent as a whole.”32 This statement of support is further affirmed by the creation of a “crisis consultative mechanism” in case of violation of the aforementioned tenets of independence and territory.

The Budapest Memorandum may be called a document full of empty promises, but the NATO-Ukraine Charter, written only two years after the Budapest Memorandum, takes things one step further and commits NATO Allies to upholding at least some of its promises to Ukraine.

The Soviet Union signed the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, which both Russia and Ukraine inherited, and both Russia and Ukraine are party to the provisions of the CSCE Treaty and the UN Charter. 33

There cannot possibly be any explanation as to why Russia was able to blatantly invade Ukraine and annex a part of its territory. The incessant argument that Russia is acting in defense against NATO expansion does not hold up in this case. Unlike the supposed agreement made between Russia and NATO not to expand further east, the Budapest Memorandum is a document that was written down and signed according to international protocols. Ukraine received its written assurances for security; Russia, perhaps fearing taking a subordinate role, did not. In the NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997, it was agreed that NATO would not deploy any significant military hardware or personnel in the new member states, such as Ukraine. NATO has upheld its promise and written assurance.34

The NATO-Ukraine Charter ends with the following last statement: “NATO Allies have no intention, no plan and no reason to deploy nuclear weapons on the territory of new members nor any need to change any aspect of nuclear posture or nuclear policy - and do not foresee any reason in the future to do so.”35

In March 2014, following the unlawful referendum in Crimea, the consultation mechanism outlined in the Budapest Memorandum was enacted.36 Suddenly, the Budapest Memorandum became relevant once more and Ukraine breathed a sigh of relief. Since then, countries such as the US and Canada, the European Union as a whole an individual European countries have enacted sanctions against Russia for its actions in Ukraine.37

This was a delayed and underwhelming response, but the Budapest Memorandum did serve its purpose in relieving some economic tensions following 1994. Inflation in 1994 decreased to 150 percent, total trade volume grew by 32 percent, Ukraine’s trade with the West grew by 40 percent, and for the first time in 60 years, Ukraine began exporting its grain.38 Since 1992, Western firms have been among the top investors in Ukraine and the European Union drafted its support strategy for Ukraine in 1994.39 Ukraine has avoided being shackled to the Commonwealth of Independent States during that time, and today enjoys a visa-free regime with the European Union and closer economic ties with the West than ever before.40 The Budapest Memorandum put forth momentum in the relationship between Kyiv and Washington D.C. that has continued to this day. Ukraine has been able to show the world its commitment to Western values, but it has paid a dear price for it.

Henry Kissinger continued his thoughts on deterrence in Diplomacy by positing, “Since deterrence can only be tested negatively, by events that do not take place, and since it is never possible to demonstrate why something has not occurred, it became especially difficult to assess whether the existing policy was the best policy or just barely an effective one.”41

This is the case of the Budapest Memorandum; from America’s point of view, it was certainly either the best policy it could have toward Ukraine or just barely an effective one. In the post-Cold War world, there was little distinction and little room for error.

The credibility of security assurances is at stake, as is world security. In 1994, the US wrote Ukraine a blank check when signing the Budapest Memorandum along with Russia and the UK. It is not quite accurate to say that the US never expected Ukraine to cash in on those promises written in the Budapest Memorandum, but the US should have anticipated that there might come a time when it faces a similar situation and will need to learn from its mistakes.

In negotiating with North Korea on nuclear proliferation, North Korea may easily look to Ukraine and the Budapest Memorandum as an example of those mistakes, which would undermine the case for sovereignty and territorial integrity, the most basic needs of every state, around the world.

REFERENCES:

1. Budjeryn, Mariana. "LOOKING BACK: Ukraine's Nuclear Predicament and the Nonproliferation Regime." Arms Control Today 44, no. 10 (2014). Pg. 38. ^

2. Goncharenko, Roman. “Ukraine’s Forgotten Security Guarantee.” Deutsche Welle. (DW.com) 05 Dec 2014. ^

3. See above. ^

4. See above. ^

5. United Nations General Assembly, Security Council letter 7 December 1994 [from the Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation, Ukraine, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General on the General and Complete Disarmament and Maintenance of international Security], 19 December 1994, A/49/765*, S/1994/1399*. ^

6. Goncharenko, Roman. “Ukraine’s Forgotten Security Guarantee.” ^

7. Emily Crawford. "Introductory note to United Nations General Assembly Resolution on the Territorial Integrity of Ukraine." International Legal Materials 53, no. 5 (2014). Pg. 930. ^

8. Budjeryn, pg. 35. ^

9. Pifer, Steven. “The Budapest Memorandum and US Obligations.” Brookings Institute. (Brookings.edu) 04 Dec 2014. ^

10. Kissinger, Henry. Diplomacy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994. Pg. 608. ^

11. Kissinger, pg. 609 – 610. ^

12. LARRABEE, F. STEPHEN. "Ukraine's Place in European and Regional Security." Harvard Ukrainian Studies 20 (1996). Pg. 255. ^

13. Pifer, Steven. “The Budapest Memorandum and US Obligations.” Brookings Insitute. (Brookings.edu) 04 Dec 2014. ^

14. Garnett, Sherman W. "Ukraine's Decision to Join the NPT." Arms Control Today 25, no. 1 (1995). Pg. 7. ^

15. Garnett, pg. 9. ^

16. Budjeryn, pg. 35. ^

17. Garnett, pg. 8. ^

18. Garnett, pg. 9. ^

19. Larrabee, pg. 255. ^

20. Larrabee, pg. 250. ^

21. Riabchuk, Mykola. "Ukraine's Nuclear Nostalgia." World Policy Journal 26, no. 4 (2009). Pg. 100. ^

22. Larrabee, pg. 255. ^

23. Cirincione, Joseph, Jon B. Wolfsthal, and Miriam Rajkumar. Deadly Arsenals: Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Threats. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2005. Pg. 374. ^

24. Garnett, pg. 8. ^

25. Garnett, pg. 7. ^

26. BESEMERES, JOHN. "Russian Disinformation and Western Misconceptions." In A Difficult Neighbourhood: Essays on Russia and East-Central Europe since World War II. Australia: ANU Press, 2016. Pg. 358. ^

27. Mroz, John Edwin, and Oleksandr Pavliuk. "Ukraine: Europe's Linchpin." Foreign Affairs 75, no. 3 (1996). Pg. 53. ^

28. Besemeres, pg. 365. ^

29. Mroz and Pavliuk, pg. 53-55. ^

30. Larrabee, pg. 249. ^

31. "Charter on a Distinctive Partnership between the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and Ukraine." Harvard Ukrainian Studies 20 (1996): 340-46. ^

32. See above. ^

33. Synovitz, Ron. “Explainer: The Budapest Memorandum and its Relevance to Crimea.” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. (RFERL.org). 28 Feb 2014. ^

34. Besemer, pg. 364. ^

35. "Charter on a Distinctive Partnership…” ^

36. Budjeryn, pg. 38. ^

37. Goncharenko. “Ukraine’s Forgotten…” ^

38. Mroz and Pavliuk, pg. 54-56. ^

39. See above. ^

40. “Ukraine Celebrates Visa Free Travel to EU.” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. (RFERL.org) 11 June 2017. ^

41. Kissinger, pg. 608. ^

Read more:

- The Budapest Memorandum: Brother, Can You Spare a Security Assurance?

- Austrian neutrality is no model for Ukraine

- Is Neutrality a Solution for Ukraine? | Infographic

- Non-fulfillment of Budapest Memorandum showed the absurdity of disarmament, Turchinov says

- Moscow refuses to discuss Budapest Memorandum

- Was Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament a blunder?