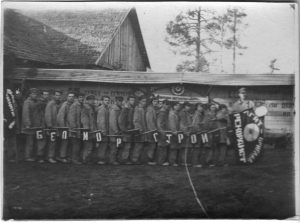

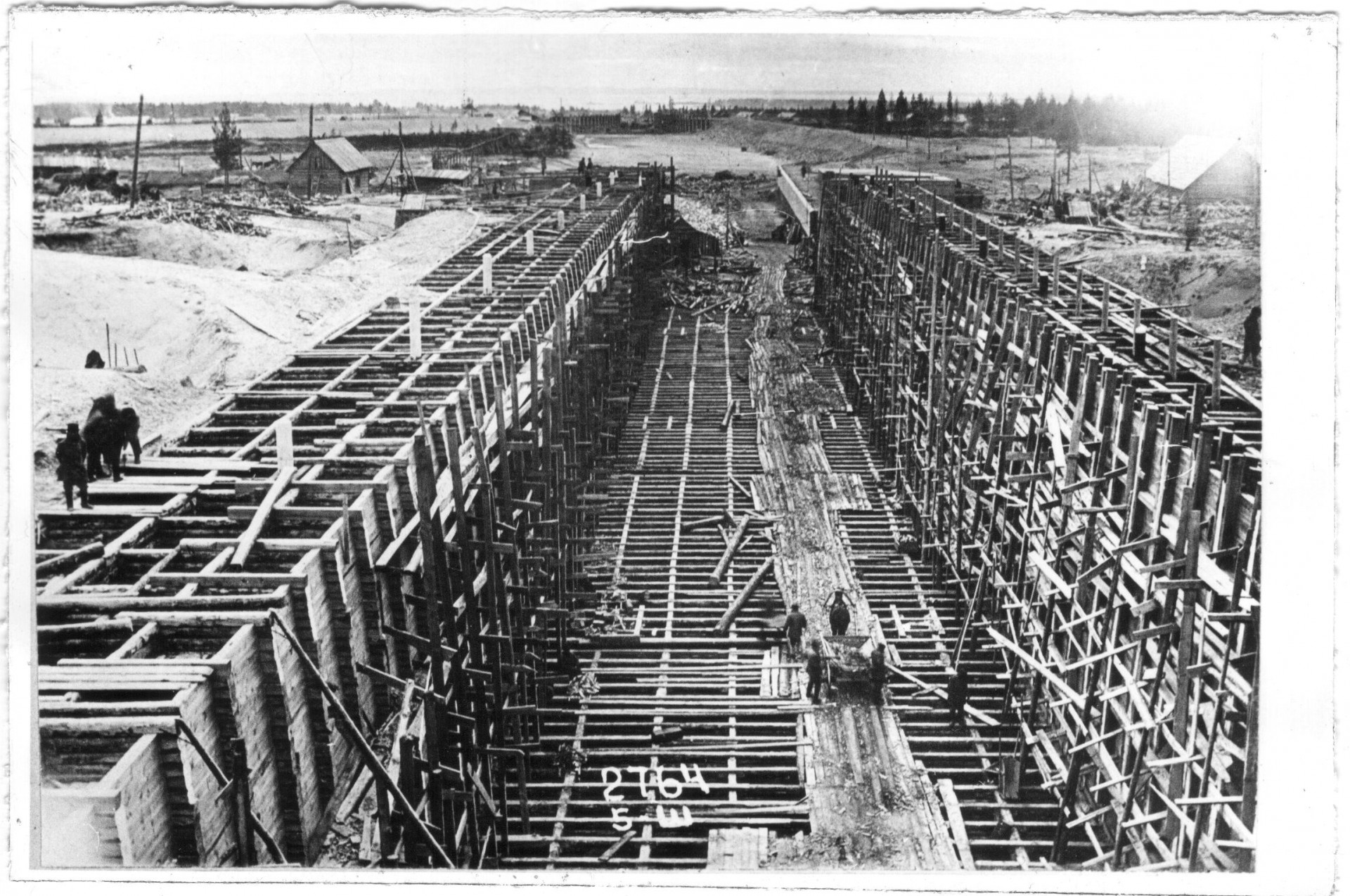

In Petrozavodsk on June 1 began the trial of one of the most amazing people I have ever known – local historian Yuriy Dmitriev. He has dedicated his life to the dead. He is accused either of producing child pornography or illegal possession of firearms – it is uncertain which. But this case began 80 years ago – in the woods near the first lock of the White Sea – Baltic Sea Canal.

I found out about Dmitriev only this year, after he had been arrested. My friends told me about an odd Karelian member of the Memorial organisation, which records the Soviet Union's totalitarian past, arrested for allegedly producing child pornography. I came home, googled him and saw pictures of a lean, bearded guy with grey dreadlocks and a dour expression. Because of the nature of the charge, it was difficult to know what to think. It was baffling! On the one hand, you could hardly imagine a Memorial member would go for such exotic stuff. On the other – an old proverb goes : 'there is no smoke without fire'.Was it pure fabrication? Just a set up? Surely they couldn’t have just made it all up?

The site of Russia’s Investigation Committee claims that Dmitriev had taken pictures of his eleven-year old foster daughter, N. for the purposes of pornography. The TV Channel ‘Russia-24’ made a whole program showing Memorial not only as a group of ‘foreign agents’ but also a nest of pedo vampires. At the center of the story was a dissipated old man who had abandoned his own children and taken in a girl from an orphanage to sell pornographic photos of her on the dark net.

I asked my friends who work at Memorial – they maintained that Dmitriev had taken pictures of his daughter for the social services. But they sounded a bit vague. It was as if they themselves did not really know what had happened. They did not believe the charge of course, but they also could not fully explain it. There was very little coverage in the press. It was as if everyone wanted to distance themselves from the words ‘child pornography’. One wanted to forget about it. And I did forget.

It was not until later that I decided I wanted to get to the bottom of this odd story – whatever it was that turned out to be at the bottom. The only thing I knew about Yuriy Dmitriev was that twenty years ago he had discovered Sandarmokh, a burying ground for those shot as part of the purges of Stalin’s time.

PRICKLY

“He’s a kind of unusual guy…” – those were the words I heard again and again from almost everyone whom I started asking about Dmitriev. “He could easily tell you to go f*** yourself if he feels like it...”

“He’s very straightforward, he doesn’t think ahead. If someone pisses him off – he’ll just tell them what he thinks…”

“He just laid himself out in front of me in the first few hours after we met, like a pack of cards. He doesn’t hide anything at all…”

“No, what can you say, he’s a warrior, a real warrior. He’s done so much on his own…”

“It’s difficult to describe Dmitriev in words, he just swears all the time and smokes Belomor cigarettes. He’s got a cat, a daughter and a granddaughter at home. They all cling to him, and he tells them ‘Form a queue, sons of bitches!’ When he was seeing me off he said, ‘That’s it. Piss off.’ But it’s all said with a smile – with irony, kindness…”

“I don’t think he was ever afraid of anything in his life. Maybe only that he would lose Natasha.”

At first I only had access to an interview that my friend Irina Galkova, the director of a museum run by Memorial had done with Dmitriev last summer.

"Even before I went to see him relations were strained," Irina says, "I called him, I said, ‘I’m coming to Petrozavodsk for work, and I’d like to meet you.’ And he says ‘Ok, let’s see what sort of a young lady you are…’ Man, who the heck do you think you are, so condescending! But he was quite capable of saying it to any ‘young lady’, regardless of how important she was."

I talk to various people who know Dmitriev. In Moscow I talk to two refined well-bred women – Irina and Olga Kerzina, the director of the Moscow College of Cinematic Art. They are both trying to help Dmitriev. From what they tell me I begin to understand that he really is a very unusual and independent-minded guy. They describe someone who is abrupt, emotional, difficult (nearly everyone uses the word ‘prickly’) – but at the same time someone who is direct and extremely open, a skilled labourer with the temperament you find in Shukshin’s stories.

When he was young he studied at a medical college to be a paramedic, but dropped out. He was locked up for a couple of years for being in a fight. Then he worked as a plumber in a sauna and laundrette. Later he was some sort of boiler-room supervisor in the municipal heating centre. Then a laborer at a mica factory. He took tourists around Karelia and learned how to survive in the woods. He got married and had two kids, and he was trying to make ends meet so he could buy a flat. During the Perestroika years he got involved in politics, like many did at that time – he had come back from prison with anti-Soviet views.

"He had an episode in his childhood," Kaizer tells. "He and is friends found a skull and played football with it. Boys don't care about such things. And then, when he grew up, he understood how horrible that was. 'Now I am paying for that..."

In 1988, eager to take part in the work on reducing the role of the Communist Party, Yuriy became a volunteer in a team working for the local People’s Deputy. A call came through to him from a reporter for the Komsomol newspaper: human remains had been found in the Besnovets garrison.

"So I say to the boss, ‘We have to see this, let’s go’. What we saw was a mechanical digger standing there, the boys from the prosecutor’s office, the investigating officer, local officials of all suits and colours, there were probably about fifteen of us there. Everyone is standing around, no-one knows what to do with what they’ve found. But I had studied at a medical college, I knew a bit of anatomy, I figured out where the head must be from how the bones were lying; I took out the skull, cleaned it, and I saw there was a round hole in the occipital lobe. That person had been executed."

So what are we going to do? "Let’s bury them again. Who cares!" I say: "Guys, wait – we can’t just do that. We have to give them a proper burial." "That’s not what we’re here for."

Everyone is standing there, looking at each other. That’s what people are normally like – lazy, no-one wants to take any more work than necessary. I said,"Well, if it’s all sort of equilateral to you all, then I guess I’ll deal with it…"

"So for a few weekends after that I just made a trip there, collected the bones together, put them in sacks and took them away to a garage. Once I found a shoe with an old split overshoe. At the back of the overshoe there was a piece of newspaper, to stop the overshoe leaking. I took the clue to the prosecutor’s office. They said, ‘It’s illegible.’ I got a Kolinsky sable hair brush and some baby soap – I spent a couple of weeks working on that newspaper. When the text started to appear, I went to the library to find out what newspaper it was. It was ‘Red Karelia’ for September 1937..."

THE FIRST PARTY

Nothing was heard again of the people who were taken away on these barges. They did not arrive anywhere. They did not resurface in any documents or memoirs. It was rumoured that the barges had been scuttled in the White Sea. For decades relatives were given false information: “sentenced to ten years without the right to write or receive letters”, “currently in the distant labour camps”, “died of pneumonia”, “died of a heart attack”... It was only during the advent of Perestroika that it was revealed that all these people had been executed by shooting.

The way it was done was as follows: the convicts were called one by one out of the cells – purportedly for a medical examination. They were taken to a ‘hand-tying room’ (the prosaic technical term used by the KGB). After the name had been checked off against the list, the guard said ‘Fit for transfer’. That was the cue: two KGB staff then grabbed the convict’s arms, twisted them back, and the third would tie them hard together. If the convict shouted, he was ‘immobilised’ by hitting him with a truncheon over the head and stifling him with a towel – until he lost consciousness. The executioners were very scared of shouting: the convicts were not to understand why they had been brought to Medvezhya Gora. Those accidentally killed were taken to the lavatory. When about 50-60 people had been gathered together, the convoy started carrying them out to the back of a lorry, stacking them up and covering them with canvas.

The caravan of heavy vehicles, with a passenger car at the back, would go out into the woods. The team working out in the woods would already have prepared deep pits in the light sandy soil.

Camp-fires were lit nearby – to keep the convoy warm and to provide light. The lorries would drive up to the pits, and people would be taken out of the back one by one. The executioners were down in the pit. Most of these executions were themselves carried out within 18 months of these events – as were many of those who took part in the Great Terror.

It is from their cross-statements that we know how the executions took place. “Once in the above-mentioned pit, we ordered the arrested person to lie face down, after which we shot the arrested person point-blank with a revolver,” - that is what Security Service Captain Matveev wrote in his statement.

After they had finished with one party, some of the execution team returned to Medvezhya Gora to get another, and some stayed behind to dig fresh pits. Up to four trips like this could be made in a single night. Women were taken separately. The operation would be wrapped up by 4am.

“Once, as we were proceeding, the goods vehicle containing people broke down and stalled in the village of Pindushi. At this time one of the convicts started shouting, which could be heard by passers-by. In order to prevent the loss of secrecy in relation to our work it was necessary to take appropriate measures, but it was completely impossible to shoot inside the vehicle, and it was also impossible to tie up the mouth with a towel since arrested persons covered the floor of the lorry in an unbroken layer with no gaps. I therefore, in order to pacify the shouting convict, ran him through with an iron stake as with a bayonet, and thus stopped him shouting.”

PEOPLE DON’T GO THERE

Dmitriev became friends with the chairman of the Memorial group in Petrozavodsk, Ivan Chukhin. Chukhin was another amateur: a lieutenant-colonel of police who had become interested in the history of the White Sea – Baltic Sea Canal and had immersed himself completely in the past. Chukhin started putting together a book, ‘Remembrance lists for Karelia’ for 1937-1938, the years of the Great Terror. Dmitriev started helping him.

"I sat for hours in the FSB archive, filling out all those cards, several thousand of them – date of arrest, little details like that. Then when I ran out of cards I realised there were great gaps in the lists. I went to the FSB again and said, ‘I don’t need the case files. Give me the ‘troika’ protocols with confirmations.’ That was something! They wouldn’t let me take copies or photos. If I was to copy them out by hand – how much would I manage to do in eight hours? I would take a dictaphone and dictate the protocols and the confirmations of execution attached to them in full… Word for word, letter for letter. I would come home, and I would spend half the night transcribing them, copying them, correlating the executions with the lists of those purged. Then I’d go there again, dictate, and so on. That was how we finally got to a more or less accurate set of data."

That was how a mica factory labourer became a historian. There was no end in sight to the work, so Dmitriev left his job. The family lived on his father’s pension – Dmitriev’s father knew a lot about his son’s work and helped him as much as he could. Dmitriev, in his direct way, gave tribute to this on the title page of the book, ‘To my father Alexey Filippovich and my mother Nadezhda Ivanovna, who fed me and my children for four years.’

When he had read the archives, Dmitriev realised that there must be many execution burial grounds in Karelia. But they were top secret, the precise location was never specified in the documents. Even those in charge did not know where the execution was taking place – only the head of the execution team and the operations staff. There was only occasional indirect evidence in the confirmations of execution. So Dmitriev started searching. He would spend the winter in the archive, and in the summer he would go out into the woods. He already knew what the execution pits would look like.

‘There was one time when a digger was excavating and they found bones. Dmitriev drives up and they’re continuing, digging away. He tells the digger operator, ‘If you carry on digging I’ll shoot you.’ He would never have done it, obviously – but he isn’t afraid of anything."

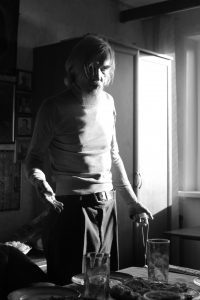

He found a German shepherd on the street, called it ‘Witch’ and taught it to find graves. They became inseparable. The two of them would spend months out in the woods together. Everyone knows Dmitriev: a lean, abrupt guy, always wearing a sailor’s shirt and camouflage, always smoking his Belomor and with Witch in the back seat of his broken-down Niva.

"Sometimes he would take a couple of alcoholics with him, quite smart, and both called Vasiliy. When they wanted to go to the village to buy a drink, he’d tie them to a tree or tie them together. But they were never annoyed by him."

"His car was always in such a state! Once when he took round a French woman journalist the actual floor was missing. He just had boards there, and she could see the tarmac. Yuriy says, ‘It’s that way on purpose. The brakes are bad, and sometimes I use my feet…’’

"He can find out everything he needs to know in about ten minutes. He goes up and talks to all the grandmothers. He taught us what questions to ask. You don’t ask about those events directly, instead you say for instance, ‘Where are the places that people do not go around here? What places are people afraid of?’’

All the graveyards were camouflaged.

"In Sulazhgor I went nearly crazy once… I know how a person is put together, where each bone of the skeleton fits in. But in Sulazhgor human bones were mixed up with others – I could not tell what. I went to the vet – apparently it was pig bones! There was a cattle graveyard there. What for? A man out hunting passes by. The dogs smell something, they start to dig. The chances are he might take a look and find a body. So they would always put a pig or something on top and say, ‘This is a cattle graveyard, please don’t walk around here."

SINK-HOLES IN THE GROUND

In 1997 Veniamin Iofe and Irina Flige, two Memorial members from St Petersburg took Dmitriev with them to look for the place where the first party brought from Solovki was shot. It was really difficult. Medvezhya Gora station is surrounded by taiga. The only indication in the statements was that the lorries with convicts passed through the village of Pindushi. That meant the shootings must have been carried out somewhere off the Povenets road. From the number of trips per night and other indirect evidence the Memorial members figured out that the journey would have taken around half an hour, ie that it was about 20 km long.

Times were different then to nowadays – the local government did what it could to help, the local army officers gave a team of soldiers to help with the search.

‘The first lieutenant and I are walking down a path in the woods, and I’m thinking: what place would I choose? In one of the statements taken during questioning I read that the operatives were told to go no further than 10 km from the place where the convicts were being held, where the shots could not be heard, and the light from the camp-fires and the headlights of the lorries could not be seen. Here? No, it’s too close to the road. Over there? Could be, but better further along. Yes, this would be it… The moment I thought that – I started noticing rectangular depressions in the ground around the road. The officer and I looked around – they were everywhere, we could not count them…"

As far as the eye could see, the woods were full of graves. The first excavations contained skulls with bullet holes. From the number of graves, it was clear straight away that it was not just that first party from Solovki who had been shot here, but many more. Many of those people were already known to the Memorial members. There were people among the executed there who had so many letters after their names, they would not fit on one close-typed page, the list of whose publications would fill a whole exercise book. There were many educated people, white army soldiers and officers and, of course, priests – four of those priests have been canonized by the church. It was one of the biggest mass graves from the years of terror under Stalin – on the same scale as Levashovo, Butovo, Kommunarka, Kuropaty, Katyn.

The place had no name. Dmitriev looked up the old maps and found Sandarmokh common marked nearby. That’s what they decided to call the place they had found.

SANDARMOKH

The North is a quiet place. Sounds – the chug of trains, the rattle of stones poured out of the back of a truck, the whine of a car engine on the road – break the silence for only a short while. Sandarmokh is three hours away by train from Petrozavodsk to Medvezhya Gora station, then twenty kilometres on the bus which goes to Povenets. The turning is easy to miss. After the turning it is four hundred metres along a path in the woods, and there is a small clearing with a sharp stone and wooden chapel. Further on it is just woods again, the usual Karelian woods, tall pine-trees for ships’ masts. Each pine tree has on it the portrait of someone who was killed here. You can smell the pines. The snow crunches under your feet. The shadows look purple on the snow. A woodpecker’s rattle sounds. From every tree around you, people are looking on, black and white photos. I walk through the forest, among the trees. They are everywhere – thousands of people. I start looking closely at them: every photo is like a letter. The person has only an instant to try to tell you who he is, what sort of a being he was, what it was like to be that being. They were photographed while they were alive, but it is as if eternity has taken aim at them. In this life, all these people became trees. Each tree is telling me who it used to be.

I get lost and wonder about for a long time. I come out in the clearing where a large stone stands, put up twenty years ago by Dmitriev together with his friend Grigoriy Saltup. It is inscribed ‘People, do not kill each other!’ As you come out of the woods, this banal-seeming phrase sounds like your own heartfelt, naïve plea.

My phone rings. A friend of mine who thinks I’m in St Petersburg is ringing to check whether everything is ok and tells me about the terrorist attack. I get the feeling of impending disaster. People are not learning from the past, they are endlessly prepared to do all kinds of malicious crap to one another. Standing on this path in the woods I feel keenly how precarious our safety is. Could anyone in the Russia of 1913 have imagined that a stupid terrorist attack would lead to a world war and then a civil war; that eight million Russians would die at each others’ hands, that the country would be covered in concentration camps and that people would execute their brothers by the hundreds of thousands for no reason at all? It would have seemed utterly impossible. The past is reflected in the future in front of me as in a dim dark glass. It seems so inscrutable.

DOWN TO THE SPECIFIC PIT

I don’t quite understand why he is digging up these graves. He is dragging out the past which you cannot see unless you dig in the woods. ‘Last year’s snow,’ something that doesn’t affect our lives in any way. The past you do not notice in people’s conversations, in the whisper of tyres on the road, or in the gentle breeze from Lake Onega. I go to sleep on the train and dream of Bashlachev’s song:

This town is sliding and changing its name,

This address was rubbed out with care long ago,

There is no such street as that, there is no such building on it,

As the house where the Absolute Guard holds a party all night...

I wake up realizing it is this – this is what made Dmitriev dig all these years. He was trying to find something, to grasp hold of something: something that isn’t there. A forgotten moment. Something behind you which disappears as soon as you turn around.

"He’s not any kind of historian at all," Irina Galkova, the Director of the Memorial museum says. "But his knowledge is astounding, and he has an amazingly tenacious instinct for detail – both physical and archive detail. I don’t know anyone else who could have gone through thousands of case files, picking out the same tedious dates out of them, comparing it all, filling out cards… When he digs up a grave, that is quite a macabre thing in itself. But apart from that there is a mass of boring work comparing, measuring, and noting corresponding details. The point of it all is to find a confirmation of execution which corresponds to a specific grave. That confirmation of execution then allows you to name those who were killed – those specific people who are lying in that pit. It’s an unbelievable task. No-one else in Russia is doing it just because it is so inefficient, it is monotonous,and it is exhausting – never mind all the rest of it."

The discovery of Sandarmokh became the second turning-point in Dmitriev’s life. He spent many years immersed in the lives of those who had been executed there. Over the course of ten years he collated most of the confirmations of execution, accounting for approximately seven and a half thousand people. Sandarmokh is the only execution location in Russia in which most of the names of those killed are known for certain, many down to the specific pit where they are buried.

Gradually the number of objects which had been found in the pits and which had belonged to those executed built up to such an extent that Dmitriev decided to put together a museum. He rented a basement in the centre of Petrozavodsk and renovated it. People started bringing him other artefacts – padded winter coats, picks, wheelbarrows. He had no shortage of documents. The initiative foundered, as it so often does due to rent arrears: Dmitriev was, let us be honest, not a born fundraiser. A few months later he moved his exhibition to a garage.

KATYA

Dmitriev’s friend Ivan Chukhin was killed in a car crash in 1997, not long before the discovery of Sandarmokh and the publication of the Karelia Book of Remembrance. Dmitriev got a job as a security guard. For the last ten years he was working in an old abandoned military plant on the edge of town. It’s a tall building with broken windows and empty floors. It does not seem as if there is anything there to guard. If you go up onto the roof you can see Lake Onega. A dog which had lost all its teeth was living there. But Dmitriev would always bring his own dog.

The job suited him very well : he had free time as well as a small income. Dmitriev carried out all his searching for free, by using his own money. He never received a ruble of grant money. He started to grow a beard and dreadlocks – his friends started calling him Gandalf. His wife left him in the mid-90s, but his two children stayed with him – Egor and Katya. They were about 10 years old at the time, born within a year of each other.

"He was on his own until they were grown up," Irina says. "The way he said it, you felt it couldn’t be any other way, ‘I won’t get a stepmother for my children’. He’s got a bit of a sentimental attitude about what a father’s duty is. Having a family which depends on him and to which he is devoted in that way is terribly important to him."

Dmitriev’s home is a bachelor’s flat on the top floor of a sixties block. Now, after his arrest, Katya lives there with her children. It smells of dogs and Belomor cigarettes. A crumbling wall with crystal glasses, a heap of rubbish of all kinds on the desk – the typical set-up of a Soviet engineer... A small plastic skeleton, a wonderful dark icon of the Saviour in the old manner, a small Ukrainian flag, a small Israeli flag, an old family photo from 1949, a rusty bayonet with a St George’s ribbon, a velvet picture-frame with World War II marshals, a globe, a photo of Dmitriev himself in his eternal camouflage, photos of friends passed away carefully set in wooden frames, a mug with its handle knocked off, the hopelessness of the Soviet Union outside the window.

Katya is a little over thirty. She is a bit abrupt, not softly-spoken, and down-to-business. She works in the Emergency Department of the local Authority Housing and Communal services Department. She shouts at her children like a sergeant-major. At first I tense up, but I soon realize that it’s just a habit – probably inherited from her father. They are nice people, and they get on well. Daniel, her son, brings me a plate of soup with mayonnaise.

"Well, we did live a bit with mum at first, but then we came back here. I do love mum a lot too, but dad was my friend. I would come round, sit myself on the sofa, and we would talk... He’s so thin! I tell him, Yuriy, how do you keep body and soul together? He really is like Gandalf. You see he’s got that little skeleton hanging above his desk – he sticks a Belomor cigarette in its teeth and says to me, ‘that’s me…’"

SEKIRKA

Sandarmokh brought Dmitriev another obsession: he decided that at all costs he would locate the other two parties from Solovki, the second and third. To do so in each case required a huge investigation - there is no room to describe the work here in detail. The search for the second party led Dmitriev to the Lodeynoe Pole area. He has not managed to find that party, though each summer he continues to comb the woods there. The third party, he realised, had never left Solovki – the sea had frozen over making navigation impossible, and the convicts were shot where they were. While searching for the third party Dmitriev discovered the shooting pits of Sekirka – probably one of the most frightening places in human history.

The testimonies of those who survived remind one of the planet Saula, out of ‘Attempted Escape’ by the Strugatsky brothers – a book which was probably inspired by these stories. The detention centre on the Sekira mountain was in a large two-storey church. It was never heated. A convict arriving there was stripped, had all his personal effects taken away and was dressed in a robe made out of a sack. Almost no food was given at Sekirka – 300 grams of something rotten tipped into the hem of the robe. All day those people, skeletal, dirty, half-dead, had to sit on special hurdles without moving, their feet only just touching the ground. In winter they sat in terrible cold, in summer covered in thousands of mosquitoes. They were beaten with sticks for disobedience, or tied up or stuffed into holes for storing food hollowed out in the rock by the monks. They slept on the stone floor covered in hoarfrost, huddling together in so-called ‘warmth groups’ (the feet of one surrounding the neck of another), or in three-layer stacks, taking turns in the outer layer. Every night someone from the lower layer would die, and the guards would drag out the body – the crazed prisoners trying to stop them because they were afraid of lying on the stone floor.

Sekirka was an extermination camp. No-one survived there longer than two months. They would prepare grave-pits at the foot of the mountain in the autumn, before the ground became hard. But it was also there that most of the Solovki executions took place. There were six full-time executioners at Sekirka. Judging by the testimonies, around ten people were shot every week. There were also mass executions: 140 former white guard officers accused of preparing an uprising (the so-called ‘Solovki plot’, fabricated by the OGPU); 125 prisoners sent to load timber for export who had written appeals for help on the logs; 148 Christian peasants who refused to work for the ‘antichrist’ – these are some of the killings that we know of for certain. In one of these burials, seventy bodies, were discovered by Dmitriev. He could not establish their names – as the Solovki camp archives are all classified or destroyed. He just gave them a funeral, asked the monks to sing the burial service and erected crosses to mark the graves.

In Solovki Dmitriev fell in love with a dead girl – Varvara Brusilova. A young aristocratic woman, a nurse, the daughter-in-law of a famous military leader of the First World War, General Brusilov. In 1922 she was sentenced to be shot for protesting against the looting of churches. Her husband and her father-in-law went over to the Reds in an attempt to save their lives, but Varvara stayed true to her beliefs. She took no part in any public protests, and her only crime was not concealing her views. She refused to repent during her trial. "I do not plead guilty to propaganda. I will meet your sentence quietly, since, according to my religious beliefs, there is no death. I do not ask for mercy or clemency." Guided by political considerations, Trotsky commuted her sentence of death to internment at Solovki.

Varvara’s husband was captured and shot by the Whites. Her little son died while she was in the camp. Varvara was interned at Solovki, with a brief break, from 1922 to 1937. All this time she spoke out fearlessly against the Soviet regime, she prayed openly, she repeatedly refused to work, and she constantly went on hunger strike. Again she was sentenced to be shot (the sentence was again commuted). But in the end, of course, she was executed – on the night of the tenth of September 1937, near the eighth lock of the White Sea – Baltic Sea Canal.

Her dramatic life, her temperament, the stubbornness of this young woman won Dmitriev over – he had clearly found a kindred spirit. He would always tell everyone he met about her. He shifted a mass of archive documents trying to find any small piece of information about her, and seems to have created some sort of personal cult. Each summer he would travel to the eighth lock, trying to find her grave. He could not find it.

"As I look at it," he would say, "it’s because I’m not ready to meet her yet. I’m a patient man. I’ll go as often as I need to, and I believe that, when I am ready, the Lord will allow us to meet."

CHARON

I keep trying to understand and I keep asking: what was it that made this guy devote thirty years of his life, without any reward at all, to this disgusting and tedious shifting of bones and archive catalogues, and going on journeys to the world of the dead? He located one burial ground – fine, even two or three – ok… But – for thirty years?

Then I realize that Dmitriev has got infactuated with history, on its ability to plunge you into the lives of others, so that you suffer, hope and fear along with them. He is hooked on the perspective it gives you on our country – allowing you to see it not as the two-dimensional screensaver of the present, but in the three-dimensional magic lantern of time, as a melancholic but beautiful pattern of interwoven lives.

An academic historian can never really touch that life, and can never make it his own. It always remains behind a line he does not cross, the thin, transparent film of time. But Dmitriev discovered a magic ritual which made the lives of those people a part of his own life. He would dig up the executed, give them names, give them a funeral – and he became part of their lives, all these people became his family. Their bones were of his bone. He was Charon, ferrying a particle of their souls back to the world of the living. He had a relationship with the dead.

Once construction workers found some bones underneath a children’s playground. They turned out to belong to a German private, 17 or 18 years old. Yuriy took the bones away and arranged a funeral in the village of Peski. With his own money he put up railings and a gravestone, with the inscription, ‘In memoriam der Kreigsopfer - vermisst, aber nicht vergessen,’ ‘To the victims of war, vanished, but not forgotten.’ He says, "War is a sordid thing, it was not this boy who started it…"

Another time he remembered the grave of a Soviet private. Thirty years ago he had seen that grave on the outskirts of a little village in the Pryazhino district, deep in the woods. The village had long disappeared, and they started felling timber commercially in the area. Gandalf was worried that no-one was looking after the grave, that it would get overgrown and disappear, and that the lumberjacks would flatten it with their heavy machinery. In the end he and one of the Vasiliys went there. They had to spend ages looking for it, but they found it. They dug up the bones and took them to a larger village, closer to where people lived, and re-interred them there. Dmitriev agreed with the locals that they would look after the grave. He could not leave the private alone in the woods.

It was only natural that Dmitriev became a believer, a mystic. He said he could hear the voices of the dead – both during his sleepless nights looking over their records, and in the rustling of the forest branches.

"At the graveyard near the eighth lock of the White Sea – Baltic Sea Canal I lit a candle and began to pray for the repose of the souls of the dead, and then I heard it all around me: remember me as well, and me, and me…"

During these thirty years Dmitriev has accomplished an astonishing amount – no-one else in Russia has uncovered so much. He was writing the history which had simply not existed before he came along. And he was gradually changing the world around him. Not every historian can say the same. One after another, places which gave people pause for thought started to appear in Karelia. Everything was as usual, it seemed, but having lived there all their lives the local people realised that execution graveyards were everywhere around them. Something had to be done with that knowledge. One cannot turn away from it, forget what we were talking about, and print some new textbooks...

"A memorial plaque was put up here to honor First Secretary Kupriyanov," Kayzer tells me. "It turns out Kupriyanov was a member of a ‘troika’ tribunal sentencing people to be shot! What do you think Yuri did? Did Yuriy protest? No, he simply came up with a ladder and unscrewed the damned plaque..."

DANGER

From talking to his various friends, I realise that in the last six months Dmitriev was clearly on edge. He said a number of times that he expected to be arrested.

"The last two times I saw him, he said he would be locked up…"

"He said that the black vans were coming. He would joke, ‘They’ll either lock me up or kill me.'"

Gandalf felt that he was being watched, but he didn’t realise what it was that he ought to have hidden. In November last year Memorial published the notorious ‘executioner lists’ – lists of the names of NKVD staff who took part in the Great Terror. Dmitriev did not participate in this work, but early in December he started getting anonymous calls from someone trying to find out if he had records of executioners.

"He had been telling me for ages that someone had been rooting around his computer, that the phone was being tapped," Katya tells me. "I told him, ‘stop being funny, James Bond!" Then he calls me, "Come tomorrow morning, stay at the flat. Someone should be at home." I said, "I can’t, I’m working." "Can Daniel come?" I ask, "What’s happened?" He says, "Never mind…’’

On the tenth of December the district police officer came to Dmitriev’s home and asked him to come down to the station the next day about some paperwork. Dmitriev went and spent about four hours being sent round the houses about his hunting rifles. When he returned home he realised that someone had been inside the flat and had poked around his computer. Two days later Dmitriev was arrested on the charge of producing child pornography. The evidence was photos of Natasha, naked.

NATASHA

When Egor and Katya were grown up, Dmitriev married again. Together with his wife Lyudmila they fostered a three-year old girl from a children’s home, Natasha. Everyone says this was a terrifically important moment for Dmitriev. Dmitriev is from a children’s home himself (his parents adopted him in early childhood). He felt it was his duty. Social services did not want to give him the child – they said he was too old; but Dmitriev went to court, soldiered on, went to the courses for those who wanted to adopt or foster, and fostered Natasha.

"But Natasha is a smart girl – and has quite a temper," Irina Galkova says. "It seems like they didn’t see eye-to-eye with his wife… She said to Dmitriev ‘Let’s send the girl back.’ He says to her ‘Why don’t we send you back!’ So he was left alone with a child again."

The students of the Moscow Cinema school, who accompanied Gandalf in his expeditions in their summer vacations after he made friends with the director of the school, know Natasha best. They made friends with her on their Karelian field trips. They came to her birthday party in Petrozavodsk, and she visited them in Moscow.

"Natasha was growing very slowly," Olga Kerzina says. "Dmitriev was very anxious about it – he thought it might be because she had already got attached to his wife. He went round all the doctors, and they told him she was not growing because she had had an emotional shock. He wanted to find a specialist doctor, and he thought he might find one in Moscow. He was a bit obsessed about her health."

"You could see he was very caring about her: he kept telling her to do up her buttons, straighten or re-straighten something, change her clothes. ‘Right, we need to get Natasha ready for school, we’ve got to buy her a new rucksack, buy her books…’ If she was naughty – she might beat someone up for instance, he might say, ‘Girlie! What are you up to doing that! I’ll set Greska on you!’’

"I think that to start with he was very inflexible," Olga Kerzina says, "He’d growl at us for sitting up late, send us off to bed. But on the last few field trips he was a lot gentler, he would sit up with us and tell us stories. From quite a fanatical guy he had become more human – and I think that was because of Natasha. When you have a child near you that always changes you..."

"He had her baptized at Sekira Mountain. It was in August, a horrible day, really windy, overcast and cold. And he really wanted to have her baptized at that particular place. We were sitting in an outdoor bathhouse on the second floor beforehand, teaching her ‘Our Father’ and the Creed. It was really deeply moving. She was very serious, because dad said she had to learn it. And when it was over the sun came out – it was unbelievable. He was very happy, and she was very happy. There was so much love there. What happened afterwards is monstrous, because he really, really loved her."

Once, when he was reading Natasha ‘The Wizard of Earthsea’ Dmitriev fastened on these words: "And the truth is that as a man's real power grows and his knowledge widens, ever the way he can follow grows narrower: until at last he chooses nothing, but does only and wholly what he must do..."

Gandalf liked this idea, he felt that it was appropriate to his life. Afterwards, when people asked him why he was so stubborn, he retorted with that very quote . That book of course is about a wizard who summons a fearful and mysterious Shadow from the world of the dead.

THE ARREST

"When it happened I had a fever of about 40C," Katya says. "I was in shock. They kept me waiting in front of that temporary detention centre as well, I was standing in front of the metal gates,and no-one was taking any notice of me. I could not find Natasha either. The investigating officer would not talk to me,and I was shouting down the phone and hysterical. I couldn’t understand anything at all. Then they let my father make a phone call, and he says, ‘You know, they are trying to pin some sort of pornography on me, that I put pictures up on the internet…’ What a load of rubbish, when he doesn’t even know his left from his right hand concerning the internet. He is computer illiterate !… He says, ‘Katya, I don’t understand anything either, but they’ll kill me in prison if I’m put away for this… It’s from eight to fifteen…’ I said, ‘Days?’ ‘Years !'"

At first, no one could understand anything. Then it turned out they were talking about pictures of Natasha which Dmitriev had taken for the social care services.

"I called Natasha – her phone is turned off. It’s late, school is nearly out, where is she, I don’t understand! I went there as quickly as I could, then I went home, she’s not here… I nearly went crazy. Then she called me at night, ‘Where’s dad?’ The social services had taken her out of school at ten in the morning while he was being arrested, and taken her to a care centre. I went to look for this centre. When I got there, the women working there were nice. They sympathised and they let me see her. She had already told them everything, how she loves her dad, how she loves me, that she has Sonya and Daniel, and that she does self-defence. She wouldn’t let me go. ‘Why didn’t dad come?’ I tell her, ‘If dad can’t come, then I’ll come and get you, but you have to wait.’ Then the social services called me. They said Yuriy Dmitriev’s relatives are not permitted to talk to Natasha as the investigating officer has forbidden it."

Natasha spent about a month in the care centre. Then they sent her away to her natural grandmother in the north of Karelia.

"When Natasha read about our father on the internet, she called me. ‘Katya, why is this happening?! This didn’t happen! Why are they punishing him like this?’ She’s writing letters to him, telling him she really loves him, and she wants to go home. Her grandmother, to be fair, says that Natasha has already adapted to life with her, she’s already giving everyone what for – at school and everywhere else. I call her, I make her do her homework, and I make her grandmother check it."

SMOKE WITHOUT FIRE

To be honest, the idea of taking photos of a naked child seems odd to me as well at first. When you hear that someone has been accused of producing child pornography, it is difficult not to be on your guard – even if you suspect that the charge has been exaggerated. When I tell people about the case, almost everyone immediately looks tense. "Fine, but why did he take photos of her then?..."

I have been seeing various people over the course of three weeks – in Petrozavodsk, in St Petersburg, and in Moscow – and I ask them about Dmitriev, Natasha, the photos. I don’t believe the porno version, but I still want to understand what odd impulse it was that made him take pictures of his daughter naked.

Irina and other friends tell me that after the children’s home the girl was borderline dystrophic and was really behind in her development. The relationship with social services was strained at first, since there had been resistance to giving Dmitriev the child. He soon had a row in the kindergarten. The staff said Natasha had bruises, but it turned out that these were stains from newspaper that his wife had used when putting on mustard plasters. It wasn’t anything much really, but Dmitriev got worried and made it a rule to take photos of Natasha naked once a month – four photos: front, back, right and left. At first he did it once a month, then every three or four months, a year or two ago until he stopped.

"He had 144 photos on his computer in folders, sorted by year," his lawyer Viktor Anufriev says, "only nine are being used in the case. If he was interested in her sexually, there’d be, I guess, not nine out of 144, but the reverse proportion, wouldn’t there? Out of those nine, half are completely stupid - Natasha is running with Katya’s children to take her bath, or they’re sitting in the bath together. On the others she is just standing there. They say you can see genitalia on them – I cannot say, because they gave me the photos with black edits on them. Also, he once took a photo of her when she was lying asleep naked. I can tell you this quite clearly: there is no crime there, there’s nothing to discuss."

Dmitriev did not even think of deleting the photos of his daughter. But he guessed that when he was called to the police station, the idea was to get him out of the house. The irony was that he kept the photos precisely because he was afraid of losing Natasha – he relied on them as proof that she was healthy!

"You have to be some sort of pervert to see anything pornographic in them," Katya says. ‘"f a man is fifty and a girl is thirty – he already thinks it’s crazy, ‘How can they?’ He’s sixty and any woman he dates has to be fifty – and even then he thinks they’re young. What I mean is, he is in favour of equal relationships – he doesn’t understand these twenty-year age gaps, he would just stare at me, ‘But Katya, but how can you…'’’

At some point I realise that I have talked to about twenty people, about half of Dmitriev’s friends and acquaintances. And they are all telling me the same thing: he’s a wonderful guy, he worships his daughter and she loves him. No-one is even close to believing the charge. It dawns on me that they are simply telling the truth. And the charge is simply a lie. Not a half-truth, not a stretch – just a lie.

At first, Dmitriev was accused only of producing pornography. But that offence entails publication and dissemination. That was what the investigating officers said Dmitriev had been doing, as relayed by the TV channel Russia 24. But Dmitriev was uninterested in the internet, and he had never even sent the photos by email. You cannot publish anything on the internet after the fact – the falsification involved would be too complex. That may be why the accusation of dissemination was simply dropped, although the article under which he was charged remains the same.

The investigating officer commissioned an expert opinion on whether the photos were pornographic from the Centre for Sociocultural Expertise. This is well-known outfit that produces expert opinions in industrial quantities for ‘Centre E’ and the FSB. Its recent ‘works’ include an opinion on ‘offence caused to the feelings of religious believers’ in Torfyanka park by opponents to the construction of a church. They have also laid bare the essential extremism of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Four experts work at the centre: an art historian, a mathematics teacher, a PhD in political science and an English translator. These kids have been caught falsely claiming to have academic qualifications,and they are said have been involved in direct falsification (inserting additional words into a text on which they were being asked to give an expert opinion), and, of course, to have produced a large number of expert opinions on matters on which they have no relevant expertise. The centre became famous when it produced an expert opinion to the effect that a Bible which had been confiscated from Jehovah’s Witnesses was a work of extremist literature. The experts’ view was that ‘the Bible viewed as a book ceases to be the Bible, it becomes such only within the Church.’

The centre has provided an 'expert opinion' that the pictures of Natasha are pornographic – and that is the only support on which the charge is based. Dmitriev’s lawyer has applied for the photos to be re-examined by experts from any specialist sexual pathology research centre. As expected, the application was rejected by the court.

Four months later, two further charges were brought: committing indecent acts and illegal possession of firearms. The indecent acts consisted, according to the investigating officer, of taking photos of a naked child. Dmitriev’s firearms were entirely legal: he used to hunt when he was younger and lately he has taken a handgun with him into the woods – there are a lot of bears in Karelia. But a few years ago he took an ancient rusty sawn-off shotgun off some kids in the street. It was broken and could not be fired, but he still thought it was better to be on the safe side... It was this sawn-off shotgun that was found when his home was searched. His lawyer says the shotgun is impossible to repair:

"But even if you could repair it, there is nothing to shoot with – the ammunition for it has not been on sale for half a century."

THE SHADOW

I spent a long time wondering who it was that Dmitriev had offended. He was a Memorial worker from Petrozavodsk – not that well known. He did not go in for politics or human rights. Had Gandalf trodden on the toes of one of the powerful figures of this little local world? Or was it a message from Moscow with an order to put the jitters on the regional offices of Memorial? Or was all this started just so that they could put out that programme on ‘Russia 24’ (Natasha’s photos somehow became available to VGTRK, the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company, immediately after the arrest)? Or was it just a coincidence: during routine surveillance of a local activist the police hacked his computer, found the photos and decided to start a case?

But as I talk to people, gradually I start to understand. Strange as it may seem, the Shadow emerged from the overgrown graves of Sandarmokh. The burial-ground is very international – mainly because of the first Solovki party. There are many Ukrainians, Poles, Finns, Georgians, Azerbaijanis, Tatars, Vainakhs – every nation is represented there, down to Swedes and Norwegians. And every year, on the fifth of August, various delegations would come. From the start, the days of remembrance at Sandarmokh were international affairs. Officials would come, so the local authorities of the Karelian Republic always had to come as well, whether they liked it or not.

The reason they were going there was to discuss what kind of memorial they wanted to set up. It was really interesting – because these men were local big-wigs, and they had obviously never given any thought to anything like this before. They went there and had a look around. They can see there’s a Ukrainian cross, a Lithuanian cross, a stone for the Chechen victims, but nothing for their people. They were not stingy, as they did the Georgians proud.

"He’s got this amazing idea, about educating the nations," Ira Galkova said. "What am I doing in Sandarmokh? I’m educating the nations. I take a nation and explain to them: your brothers were killed and buried here. You are one people, though you are alive and they are dead. Why don’t you put up a memorial to them, you bastards!" At first I thought, "What are you on about?" But then I saw how it worked with some Georgians, and how he was educating them. And Yuriy brought a lot of people like that there. Every time the people who came really varied. They were obviously people who had only just started thinking about such things. But they had come together in that place because of him, and something had started to happen. Then afterwards, just because the memorial was already there, people started coming. It turns out that a lot of Georgians know about this place – both here and in Georgia, and lots of people started to think about our common history, how our stories are intertwined."

This went on until 2016. Then, they say, an order came through to the local authorities – do not go to Sandarmokh. For the first time the representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church were not there, the traditional procession of the cross did not take place (though for instance in 2010 Patriarch Kirill himself had led the memorial prayer). There were, however, many journalists from the official Karelian media. ‘They had special question-sheets prepared by the secret services, and they interviewed foreign guests, asking why they come here and so on. This was never used in any publication,as the information just went up to the next level somewhere…’

It was two episodes the previous year, it appears, that led to this change of mood. Ukrainians and Poles come particularly frequently to Sandarmokh – the flower of the Ukrainian educated class and many Polish priests were executed along with the Solovki party. In 2015 the ambassador Katarzyna Pełczyńska came to the day of remembrance service and formally awarded Dmitriev the golden ‘Cross of Merit’, one of the highest state honours in Poland. It was then that a mad Ukrainian grandad from Lviv in a Ukrainian nationalist uniform came as part of the Ukrainian delegation. I was told that a crowd of FSB staff followed him around, but that they never touched him, and even protected him from the local hoodlums. Nevertheless, it appears that the decision was taken to shut down Sandarmokh. All the more so, since this year marks the twentieth anniversary of the discovery of the burial ground, and also the eightieth anniversary of the Great Terror. The secret services realized that once again people would come in droves.

Anatoliy Razumov was in Petrozavodsk in February at an on location session of the Council for Human Rights.

"We discussed Dmitriev’s case, and after the session a certain person who holds one of the top posts in the Karelian Republic came up to us and said, ‘We don’t need any politics here. We don’t need people to come here and start politics!... Strange as it may seem, the geography of the place plays its part: the region is next to the border and the secret services are nervous. "

It was also last summer that a campaign began in Petrozavodsk to rewrite local history. At first, a news item was published citing Yuriy Kilin, a Professor of Petrozavodsk University. He had made a suggestion – which, after several rounds of interpretation became an assertion – that Sandarmokh might be the burial ground not only of the victims of the purges, but also of prisoners of war executed by the Finns.

"A suggestion which is unfounded," considers Irina Galkova. "It is based by analogy on the fact that the Finns used the GULAG camps for their prisoners of war. So, the argument goes, if they used the camps, they might also have carried out mass shootings. The logic is warped, because a camp is something you cannot hide, and it’s clear how it can be used, but an execution location is secret, it’s somewhere out in the woods. You cannot find it, and why would you bother anyway? But the idea had been put out there. There was the first stage, when it was just a suggestion, then a third and fourth, when it became an assertion, and a fifth stage, when it was denied that any purges had occurred at all. ‘So that’s what in fact happened – Memorial has fanned some kind of hysteria saying that it was Russians killing Russians, and in fact it was those damn Germans who did it all!’’

On the fourth of August, on the eve of the day of remembrance, the Zvezda TV channel put out a programme called ‘The further truth of the Sandarmokh concentration camp: how the Finns did away with thousands of our soldiers.’ The programme featured documents from the FSB, declassified and made available to the TV channel. The documents purported to prove that the people buried at Sandarmokh were Soviet prisoners of war. In reality, viewers were shown a SMERSH intelligence report about a small prisoner of war camp for 250 people in Medvezhyegorsk, located in a former Belbaltlag camp.

I have read that intelligence report – it states that two prisoners of war were executed. During the programme, however, the presenter said that ‘according to various data, between 19 and 22 thousand people died here. It is of course essential that a memorial to the prisoners of war is erected at this place.’

In October 2016 the Karelian office of the Liberal Democrat Party of Russia erected a memorial to ‘Russian people done away with’ at the entrance to Sandarmokh. There’s nothing there to find fault with, you might say. It is true that many Russians were killed there. But these two events look like part of the same campaign.

"Who will people listen to? What do you think? Dmitriev is the village crackpot, whereas these are respectable gentlemen with degrees…" a friend from Petrozvodsk University tells Irina Galkina.

"What about the fact that this crackpot has documents relating to Sandarmokh for seven and a half thousand people? I tried to discuss this with Dmitriev, but he waved me away, ‘It’s all nonsense. These are tame cattle - they eat from the hand they need to feed from. Whereas I’m an old wolf in the wild, I eat what I like…’’

That was the problem. It is utterly impossible to come to terms with Dmitriev. It was clear that he would continue to organize these days of remembrance for as long as he lived. And Sandarmokh is not a museum like ‘Perm-36’. It is a people’s memorial. Just to close it down would be difficult. To stop the activity they had to stop Gandalf.

Normally if a charge is pure fabrication that becomes obvious during the trial. Of course that does not change the fact that there is nothing easier than convicting an innocent man. But at least people would have understood what had really happened. Dmitriev cannot hope for that. No-one will ever see the unfortunate photos. He is accused of a sexual crime against an under-age child, and his trial will be held behind closed doors.

Of course Gandalf knew where he was heading. I have a feeling that some wise and benevolent power is over everything – Dmitriev himself, the cinema school students, the souls of the dead, the FSB staff and the TV reporters from Russia 24. That we still live in a world where people like this, and stories like this can come about. A world where God still grants to each person their amazing destiny. Where every hero can find himself a dragon to fight. Thirty years ago Dmitriev went out to meet it with a shovel in his hands. And the dragon came.

/With the assistance of Yuliya Vishnevetskaya. The text uses parts of the interview with Yuriy Dmitriev conducted by Irina Galkova in the summer of 2016.

Petition in Defence of GULAG researcher Yury Dmitriev [Memorial Human Rights Center]