The escalations in occupied Crimea on 7-8 August, in the course of which Russia has accused Ukraine of staging "terror attacks" and claims that it has foiled a "sabotage group," have left many questions unanswered about the Kremlin's versions of events, the first one being why Ukraine would try to carry out such a pointless operation in the first place.

However, the Kremlin's tradition of taking Ukrainians as hostages is quite clear, human rights activist Mariya Tomak wrote for the Russian outlet grani.ru. Mariya is a coordinator of the LetMyPeopleGo campaign, which advocates for the release of 28 Ukrainian hostages of the Kremlin illegally held in Russia for political motives. Many of them are sentenced to dozens of years in prison under conditions strikingly similar to those that Russia now accuses of being part of the "sabotage group."

The Russian-backed authorities report on 9 detained alleged participants of this "group." The identities of three of them have been revealed: the civic activist and ATO [Anti-terrorist operation - Ed.] volunteer Yevheniy Panov, Crimean Tatar Redvan Suleimanov, and Andrei Zakhtei have been announced.

Read more: A timeline of Russia’s Crimean “terror” games | Infographics

Despite the lack of information on this case, definite parallels can be traced between the "sabotage group" case and a number of other cases of the prisoners of the Kremlin, Mariya asserts. What follows is a summary of Mariya's article on grani.ru, edited for the sake of clarity.

Accusations in terrorist activities

The "Sentsov group," the "case of the Crimean muslims"

The first to be arrested as "terrorists" were four Crimeans - Oleg Sentsov, Oleksandr Kolchenko, Gennadiy Afanasyev, and Oleksiy Chyrniy. They were detained in May 2014 after Russia's illegal annexation of Crimea and accused of participating in a terrorist group under article 205 and 205.4 of Russia's Criminal Code. The accusations were based on the "testimonies" procured under torture (one of which was subsequently retracted.)

A bit later, another variety of "terrorists" appeared on the peninsula - Muslims. To this day there are 14 of them, and they constitute the majority of the Hostages of the Kremlin. They are all incriminated with the same article of Russia's Criminal Code - 205.5 (organization of a terrorist group and participation in its activities), almost all of them are representatives of the Crimean Tatar community and practicing Muslims, which, as their defense considers, is the reason for their accusations in participating in Hizb ut-Tahrir, an organization illegal in Russia but legal in most of Europe.

Panov's group, however, according to available data is being accused under a different article - 281 (preparation of sabotage implemented by an organized group).

And in both of these cases, as in all the other cases where people are imprisoned for alleged "terrorism," terrorist acts were not involved. Members of the "Sentsov group" in their resistance to the occupation of Crimea were committing actions that are qualified as "hooliganism" in Russia. The "Crimean muslims" did not commit any acts of violence; the basis for the accusation are "kitchen conversations," says Aleksandr Popkov, the lawyer of one of the accused.

Read more: The Sentsov-Kolchenko case: what you need to know

A suspicious disappearance

The case of Mykola Karpiuk

It's not clear yet how Panov got into Crimea. His relatives say that he was kidnapped: Yevheniy planned to visit his dacha together with army friends and promised to come back soon, but disappeared. Neither his friends, nor his car have been discovered yet. Ukraine's MoD has denied this story based on "unofficial data," but without any proof. But if Panov really was kidnapped, this story will very much resemble how Mykola Karpiuk was kidnapped from Ukraine - he also informed his family that he was going for a short vacation with his friends and after that somehow was arrested in Chechnya.

Read more: Russia’s “Chechen” show trial of Ukrainians, explained | #LetMyPeopleGo

In both of these cases, the question of disappearances or kidnappings of Ukrainian citizens from Ukrainian territory needs to be investigated.

Torture and false testimonies

The "Chechen Case," the "Crimean Four," the "Maidan case"

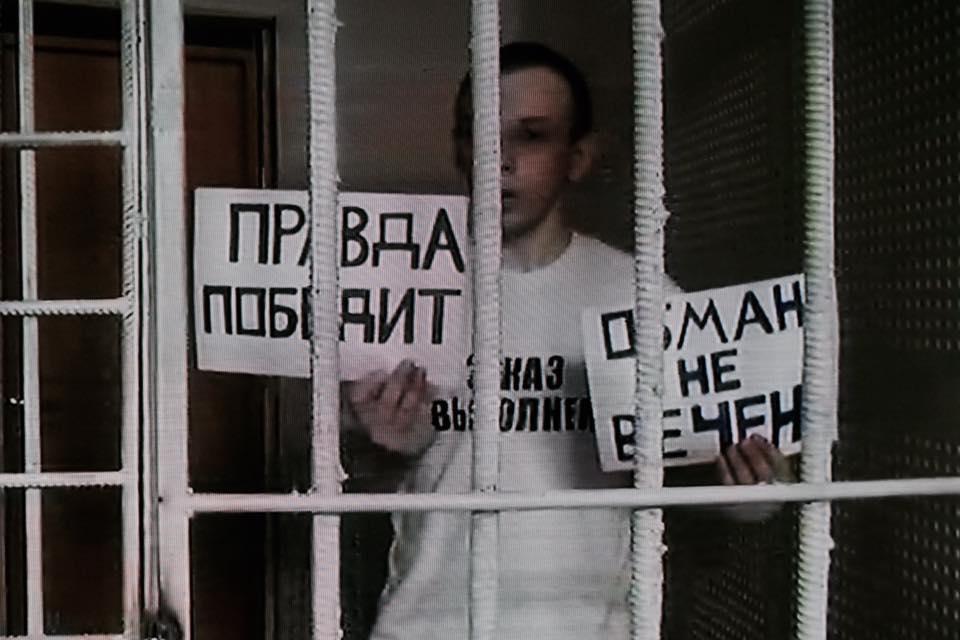

After watching the video Russian media aired with Panov's interview, many analysts noted the traces of abuse on his face. The human rights initiative Euromaidan SOS noted:

"The character of the injuries (swollen face and lips, heavy breathing) gives ground to assume that he was strangled with a plastic bag. It is also notable that he pronounced a pre-agreed text, which is indirectly confirmed by the number of cuts in the video."

This makes the newly detained Ukrainian similar to at least ten prisoners that have gone through terrible torture, with the scariest examples being Mykola Karpiuk and Stanislav Klykh, Oleg Sentsov and Gennadiy Afanasyev, Oleksandr Kostenko, and Andriy Kolomiyets.

Read more: Beaten, drugged, electrocuted. Ukrainians tortured into “confessing” of Chechnya crimes in Russia

In all these cases, torture was applied to receive a "confession." If anything similar happened with Panov, we will know about it only after independent lawyers start working with him. As a rule, in it was specifically the appearance of independent lawyers that changed the course of events in the cases when the investigators succeeded in extracting testimonies from the accused in which they "confessed" of the crimes they were accused of.

Redvan Suleimanov, a Crimean Tatar that has been accused along with Panov, is a more difficult case. His monologue, aired by Rossiya-24, looks no less artificial, but he carries no marks of abuse. As Crimean Tatar Mejlis head Refat Chubarov informed, Suleimanov had been detained already three weeks ago, however, his relatives did not go public with this, fearing to make the situation worse. It's not clear what Suleimanov is accused of. Chubarov states that he lives in the capital of Crimea Simferopol, but in the video he names the address Kosmichna 38, Zaporizhzhia (mainland Ukraine). This address does not exist, as anybody can check in google maps.

A made-up address is no news for us. We have seen them in the case of Serhiy Lytvynov: unexisting victims of "mass executions" of the Ukrainian army lived at unexisting addresses. And it's the case of Serhiy Lytvynov that most resembles Panov's, in my opinion.

Using "ordinary" Ukrainians to discredit Ukraine as a country

Lytvynov's case.

News about the "Ukrainian sabotage group in Crimea" overshadowed the recent news related to another hostage of the Kremlin, Serhiy Lytvynov. The Russian Prosecutor General dropped the accusations of massacring 39 residents of Ukraine's Donbas and committing war crimes and issued an official apology to the Ukrainian cowherd that was detained while undergoing treatment in a hospital of Russia's Rostov and has been held for over 2 years. A forensic psycho-physiological assessment has determined that Lytvynov's "confessions" of committing those crimes had been extracted by torture.

Lytvynov is now suing Russia for the damage done, and his lawyer is planning to file a defamation suit against the pro-Kremlin Rossiya TV channel for airing a show where Lytvynov was presented in the classic way of portraying Ukrainian soldiers: a "punisher" torturing infants.

What makes Lytvynov's case similar to Panov's are the accusations against the Ukrainian political and military leadership (which, of course, is behind the "criminal actions" of Lytvynov and the "Ukrainian sabotage group" in the "conscious and intentional" plans to massacring civilians in the occupied territories (in the Kremlin's rhetoric - territories that were eager to join Russia) or in the conflict zone, which the Kremlin portrays as territories where the Russian-speaking population fights against the "Kyiv junta."

Russia's statements regarding the supposed "Crimean sabotage group," accusing Ukraine of allegedly plotting terror attacks, and promising retaliation, understandably made Ukrainians anxious. President Petro Poroshenko has claimed that the incident was created by Russia as an "excuse for further military threats."

Lytvynov's case could also have been used as such an "excuse," but wasn't -first of all, there were no loud statements by Putin, and secondly, his adventures went unnoticed on the backdrop of military actions in the end of summer of 2014. However, Lytvynov's case suited the purpose of being a reason for a wide-scale military invasion of Ukraine.

Tragic and disproportionately large consequences could grow from these small cases of the hostages of the "hybrid war." I hope that in the nearest time, the figurants of the "case of the Ukrainian saboteurs" will receive the support of independent lawyers and we'll receive an opportunity to know more about the circumstances of their detention and possible use of torture against Ukrainian citizens.